Carniolan Savings Bank and Slovenian-German Relations in 1908 and 1909

UDC: 336.722(497.4Ljubljana):323.1(497.4=112.2)"1908/1908"

IZVLEČEK

KRANJSKA HRANILNICA IN SLOVENSKO-NEMŠKI ODNOSI LETA 1908 IN 1909

1Nacionalna nasprotja v avstro-ogrski monarhiji so se ob koncu 19. stoletja vse bolj zaostrovala in prišlo je do nacionalne polarizacije. V zadnjih desetletjih pred izbruhom prve svetovne vojne so nacionalna nasprotja dosegla velike razsežnosti. Vrhunec slovensko-nemških spopadov na Kranjskem predstavljajo protinemške demonstracije v Ljubljani leta 1908, ki so pripeljale do korenitih sprememb v političnem, gospodarskem in družbenem življenju. V članku je predstavljen pomen, ki ga je imela Kranjska hranilnica v slovenskem prostoru v začetku 20. stoletja. Prispevek posebej obravnava posledice, s katerimi se je hranilnica soočala po septembrskih dogodkih leta 1908, ki so močno zaznamovali njeno delovanje.

2Ključne besede: Kranjska hranilnica, vlagatelji, bojkot, naval, umik, državni vrednostni papirji, hipotekarna posojila

ABSTRACT

1At the end of the 19th century, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy experienced national polarisation. During the last decades before the outbreak of World War I, national contradictions reached considerable proportions. The Slovenian-German conflicts in Carniola culminated in the anti-German riots in Ljubljana in 1908, which led to radical changes in the political, economic, and social life. Paper presents the importance of the Carniolan Savings Bank in the Slovenian territory at the beginning of the 20th century. The article deals specifically with the consequences faced by the Carniolan Savings Bank after the events of September 1908, which strongly affected its operations.

2Keywords: Carniolan Savings Bank, depositors, boycott, bank run, withdrawals, government securities, mortgage loans

1. Introduction

1During the last decades before the outbreak of World War I, the national contradictions between the national movements reached great proportions in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. In the province of Carniola, the conflicts between the Slovenian and German national groups culminated in September 1908, when it came to the turning point in their relations. The anti-German riots in Ljubljana let to radical changes in the political, economic, and social life. The conflicts did not subside until as late as the onset of World War I. Mutual accusations and suspicions were a part of everyday life. Many Slovenian investors withdrew their savings from the Carniolan Savings Bank, mostly because it was considered as the German financial pillar in the province of Carniola. Carniolan Savings Bank had been established and operated in the territory traditionally populated by Slovenians, who spoke Slovenian. It predominantly collected deposits and managed credit activity in Carniola. Therefore, it is paradoxical that the Carniolan Savings Bank was considered a German institution, although it had never publicly or openly declared itself as either a Slovenian or German financial institution. Such indifference1 was opted for by the Board regardless of the national affiliation of the members of the Savings Bank Association. The goal was to attract as many depositors as possible. The statute of the Savings Bank stated that membership in the association and the Board did not depend on nationality, and all Austro-Hungarian citizens with a permanent address in Ljubljana could become members.2 Nevertheless, the Carniolan Savings Bank maintained this status until the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1918.

2Savings banks had a significant impact on the changes, required for the mobilisation of financial resources from the social strata that had had no access to banking services before. Furthermore, savings banks introduced dispersed financial resources to the financial market by directing capital into mortgage loans and government securities.3

3This article deals specifically with the consequences that the Carniolan Savings Bank faced after the events of September 1908, which had strongly affected its operations. Deposit withdrawals were a common reaction of the population during the periods of different economic, political, and war crises. Savings bank deposits often dropped during or after systematic commercial crises. Bank runs are events when debt holders of a single bank or savings bank demand redemption. The rapid withdrawal of deposits usually forces a contraction of credit.4 The runs in question were triggered by fears regarding solvency and the repayment of deposits. The Carniolan Savings Bank tried to restore the trust of its clients, while at the same time attempting to hedge its deposits in times of high risk. It had to ensure the security of their business and invested money. The savings deposits that the Carniolan Savings Bank had to pay off to their depositors between October 1908 and June 1909 far exceeded all of its available cash.5

2. Slovenian − German Relations Before 1908

1At the end of the 19th century, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy experienced national polarisation.6 It was not enough to be just Slovenian or German: it was necessary to show nationality in public. National struggles also intensified in the Slovenian territory at the turn of the 20th century.7 The national-political differentiation was followed by battles between the national movements. Differentiation began in the 1860s and early 1870s. During this period, it was characteristic that at the local elections, people would usually decide either in favour of the Slovenian national party, its programme and performance or against it. The opposite side consisted of people who, for some reason, did not support the Slovenian party and were satisfied with the traditional leading role of the German language and culture,8 people who believed that national differences were not as important as constitutional developments, the fight for their preservation, and the promotion of liberal ideas. 9

2National differentiation developed differently in each province. The province of Carniola was traditionally populated by Slovenians, who spoke Slovenian. The relative proportion of Germans in Ljubljana was always modest. However, in Lower Styria, for example, the situation was completely different. Germans lost the countryside, but retained the control of the city curiae in Celje, Maribor, and Ptuj until the dissolution of the Monarchy, while Slovenians were a part of a larger territory with a German majority and a German centre. In Lower Styria, after 1878, all electoral districts of the peasant curia – and after 1907, all of the rural state electoral districts – were in the hands of Slovenians.10

3From 1848 until the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the Carniolan German vision of the Slovenian national community barely changed, although smaller developments are still noticeable. Until the end of the 1870s, the German side did not oppose the Slovenian wishes for all-round progress but believed that the Slovenian nation had, until then, been underdeveloped and not fit to lead a completely independent life. They perceived the obvious and comprehensive development of Slovenians as of the 1880s as artificial – supported by the contemporaneous state and government of Eduard Taaffe to the detriment of Germans.11

4Both national movements – German and Slovenian – would use a variety of resources for defence and offence.12 Conflicts between the members of the German and Slovenian national groups quickly developed into physical altercations. Fights between Slovenians and Germans became constant, especially during Slovenian cultural and social events, which the Germans understood as demonstrations against German domination. Germans initiated disorders in the predominantly German Celje, while its opposite was the predominantly Slovenian Ljubljana. The 1903 spring demonstrations in Croatia therefore also triggered a solidarity movement in the Slovenian territory. During May and June 1903, several political protests took place against Ban Khuen Hédervári in Ljubljana, Celje, Slovenj Gradec, Trieste, Gorica, Šempeter, Nabrežina, as well as in smaller rural towns. All of these were invoked by the joint efforts of the Slovenian political parties. The gathering in Ljubljana turned into anti-German demonstrations. Protesters started throwing stones into the German Kazina building, and the police had to deal with the demonstrators. Consequently, Prime Minister Ernest von Koerber decided to prevent the visit of the Dalmatian, Istrian, and Slovenian deputies to the Emperor.13

3. September Events in Ptuj and Ljubljana

1The many excesses provide ample evidence that over time, the national struggle could attain the dimension of a “life-and-death struggle”. The contradictions between the Slovenian and German population had reached great proportions, full of intolerance and hatred on all sides during the last decades before the outbreak of the World War I. The September 1908 events, beginning with the German protests in Ptuj and culminating in anti-German demonstrations in Ljubljana, were among the most prominent conflicts.14

2The annual assembly of the St. Cyril and Methodius Society (Družba sv. Cirila in Metoda – CMD), a national defence school organisation, represented a cause for German demonstrations. The CMD leaders chose Ptuj because they wanted to show that this city was not German, but Slovenian. The Styrian Germans were not impressed by this decision. They wanted to underline precisely the opposite; that Ptuj had always been and will remain German. The German population was unsuccessful in its efforts to make the authorities ban the CMD assembly, announced for 13 September 1908. The first anti-Slovenian demonstrations took place on the evening of 12 September. The first serious incident occurred immediately after a train had arrived at the Ptuj Railway Station. On the next day, German counter-revolutionary demonstrations broke out, leading to physical conflicts between the Slovenian and German movements. The German demonstrators disrupted the CMD assembly in front of the National House.15

3According to Branko Goropevšek, the Ptuj events would probably have remained less noticeable, had they not triggered an outburst of national feelings that engulfed the other Slovenian territories and resulted in anti-German demonstrations, particularly in Ljubljana. The Slovenian population prepared a series of protests in Styrian cities and villages. 16

4The reports of the events in Ptuj provoked Slovenian demonstrations in Ljubljana. In the capital city of the province of Carniola, on 15 September, the town council protested strongly against the Ministry of the Interior. Two days later, on 17 September, the Slovenian youth organised demonstrations against the German Student Society of Carniola, which held its general assembly. On the following day, the demonstrations had become widespread. They lasted for three days, from 18 to 20 September. Because of the attacks against German shops, artisans, and traders, the Government ordered the gendarmerie and the army to intervene. On the evening of 20 September, the army fired at the protesters. During the shooting, they killed the student Ivan Adamič and Rudolf Lunder, an employee of the national printing office.17

5The Mayor of Ljubljana Ivan Hribar dedicated a whole chapter of his memoirs to the September events. He detailed the development of these events in Ljubljana and specifically focused on the military procedures: “There was, of course, much excitement around the city. The crowd was the angriest because of the military presence and its directly inappropriate behaviour, as it was, in many many cases, later possible to determine. They were not satisfied with setting up cordons in the streets: some of the troops even walked into public shops and threw people out.”18 Regarding the responsibility for the unpleasant events of 20 September, when Lunder and Adamič lost their lives, Hribar wrote: “You got what you wanted! I have just received a report that the army opened fire and that several people were killed. I refuse to take responsibility by myself, and I blame you for the spilt blood!”19 Hribar was the only one to write about the boycott of the German merchants and actions regarding the elimination of German inscriptions.

6Anton Bonaventura Jeglič, the Archbishop of Ljubljana, briefly described the events in his diary. On 22 September 1908 – regarding the events that had taken place between Friday, 18 September, and Sunday, 20 September – he wrote that terrible riots took place in Ljubljana and that Slovenians were breaking windows and damaging German-owned buildings. He believed that these events had been caused by “the general incitement of one nation against the other and the German demonstrations against Slovenians in Ptuj.” He was very pleased to emphasise that the Slovenian People’s Party did not participate in the riots and that only liberals were affected.20 In his next announcement, he corrected his misstatement, underlining that there were not three deaths but two and that the funeral was a powerful demonstration. In his opinion, the representatives of the Slovenian Liberals tried to take advantage of the situation in order to regain their leading political position in Carniola.21 However, in the article titled To the Faithful of the Diocese of Ljubljana [Vernikom ljubljanske škofije] published in the Škofijski list newspaper, he considered the moral principles in the broader context of the German–Slovenian relations. He condemned the September demonstrations of both nations: “What happened in Ptuj against Slovenians merely entailed sins against the Christian love towards one’s neighbours; and what happened in Ljubljana against Germans – the senseless destruction of windows and damage to the property of others – are mortal sins, not merely against love, but also against the justice that we owe to our neighbour. In addition, newspapers incited, maintained, and encouraged the sinful hostility and acts of sinful revenge in Styria and Carniola.” 22

7Fran Šuklje only mentioned the September events in his memoirs and judged them with the following words: “The events in Ljubljana, however, went far beyond what was commonly in our thoughts. In particular, they had a bad influence on the already compromised position of Prime Minister Baron Beck. In his government programme, Beck tried to reconcile the national oppositions and strived to achieve national reconciliation and settlement. Due to the events that took place in Ljubljana on and after 19 September and because of the ‘Germanised’ strongholds in Lower Styria and Klagenfurt, the reconciliation that Beck’s policy is based on is impossible.”23 Šuklje devoted more attention to the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in particular to the Provincial Assembly elections on 14 December 1908, won by the Catholic Slovenian People’s Party.

8A conflict also ensued regarding the inscriptions on the stores in Ljubljana. On 21 September 1908, the Slovenski narod newspaper published an article titled Only Slovenian Captions [Samo slovenske napise]: “Today at noon, our people acted in accordance with self-help principles. In groups, they approached, completely peacefully and with dignity, the shops of tradesmen that have, until today, displayed bilingual captions. They demanded that the owners remove them. Almost everywhere, this happened completely peacefully and without any commotion.”24 After the German inscriptions on shops had been removed, Slovenians started boycotting German merchants and artisans. The Germans saw economic interests as the causes of the riots. German newspapers wrote that the most recent anti-German movement had been only an introduction to full-scale economic war.25 The Germans responded in kind: their newspapers, for example Laibacher Zeitung, promoted purchases from German merchants exclusively.

9The September events were well-covered by the Slovenian press. Although the Catholic newspaper Slovenec initially devoted less attention to the events in Ptuj, on 21 September, it published a special issue about the incidents and fatalities in Ljubljana. On the other hand, as early as on 14 September, the Slovenski narod newspaper reported about the events in Ptuj on the cover. Slovenski narod devoted its full attention to all the events taking place until the end of the month. Both newspapers supported and called for economic pressure and the “each to their own” action. Therefore, in the Slovenski narod, we can read the following: “The movement for the Slovenian economic independence begins to spread. It must reach all facets of society. Slovenian traders and craftsmen also need to take part in this movement. […] They must avoid everything that strengthens their opponents. Slovenian merchants and tradesmen who serve the German monetary institutions should be held responsible for their unforgivable sin. […] Those who are wrongly against this should be aware that we will stand up against them as we stand against anybody who frequents German shops […] Slovenians, where is your national pride?!”26

10According to Dragan Matić, the September events in Ljubljana were an unusual episode for the German population, which they themselves had no influence on. According to the testimony of the Mayor of Ljubljana Ivan Hribar, the unfortunate bullets that killed Lunder and Adamič were fired on an officer’s orders. The blame for this was initially assigned to the Provincial President Baron Teodor Schwarz, as he allowed the army to fire warning shots.27 On the other hand, the military authorities justified the use of weapons and considered it as absolutely legal. The blame that this happened at all, however, was ultimately attributed to the civil authorities, the inadequate and insensitive behaviour of the provincial presidency, and the political uncertainty of the city authorities, which concealed the fact that they had a severe problem with the military assistance and with Lt. Mayer, who arbitrarily used weapons. In this way, he did more harm than good and effectively assumed a decisive role in suppressing the demonstrations.28

11The profound and irreversible consequences of the September events were felt everywhere. Although the broken windows in Ljubljana were swiftly repaired and many offenders received monetary and prison sentences, distrust and hatred between the Slovenian and German people kept intensifying. Most of the changes took place in Ljubljana. One of the examples was the city’s external appearance, which changed completely and has been, since that time, completely Slovenian. The German and bilingual inscriptions on shops disappeared and were replaced by Slovenian signs exclusively. In Goropevšek’s opinion, the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina a few weeks after the September events played a crucial role in the fact that the September riots were promptly replaced by other topics, including the momentous international political crisis that followed in the subsequent months.29

4. The Carniolan Savings Bank Between the Slovenian-German Political and National Struggles

1A long period of peace until the end of the 19th century had spurred on economic development, especially industry. However, the time after the turn of the century brought about increasing political tensions, both in Austro-Hungary and globally. The increasingly disturbing factors of the Monarchy’s economic development at the beginning of the 20th century included national tensions.30 During this period, the movements in the securities markets were significant. The Austro-Hungarian National Bank was forced to lower the interest rate due to the extensive supply of free capital. On the other hand, the time before the onset of World War I was marked by a growth in deposits, which remained steady even if considerably slower than in the previous period. There were several reasons for this. Initially, the founding activities of savings banks slowed down and diminished after, in general, reaching the greatest intensity between 1860 and 1880 in the Austrian part of the Monarchy.31 Furthermore, the beginning of the 20th century brought about the rapid development of other financial institutions such as credit cooperatives, joint-stock companies, and banks.32

2In the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, significant changes of the credit system occurred between the turn of the century to the beginning of World War I. In the new system, savings banks assumed a less prominent position, while banks, joint-stock companies, and credit cooperatives were given priority. They also developed more quickly than savings banks. The savings activities of the population turned to the long-term forms of saving, which yielded higher profits and were subject to more favourable savings conditions.33

3The political and social differences between the individual nations in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy kept growing despite the economic integration, which accelerated in the second half of the 19th century.34 However, the Austro-German economic strength was not enough to dominate the huge empire, and a dialogue with the different nationalities was crucial. The most urgent task, however, was to bridge the huge gap between the urban, industrialised, and largely rural, traditional areas.35

4In the beginning of the 1880s, Slovenian politicians attempted to take control of the Carniolan Savings Bank. They wanted to assume control, particularly in order to prevent its support of the German cultural and other societies. Moreover, their aim was to prevent any attempts at the establishment of a German system of people’s education, which was one of the objectives of the Carniolan Savings Bank’s management. Slovenian politicians endeavoured to establish a savings bank under the control of the Provincial Assembly, in which Slovenians had a majority, but failed. Simultaneously, there were tendencies to defend the national-economic positions and institutions of Germans in Carniola. German politicians strived to defend the Carniolan Savings Bank, which was considered as the financial pillar of Germans in Carniola.36

5In case of financial institutions, it was vital that they had Slovenian leadership and management, as this was in the Slovenian national interest. Otherwise, the institutions were placed on the opposite end of the political and national spectrum, as was the case with the Carniolan Savings Bank.37 The Carniolan Savings Bank was not only considered as an economic but also the political symbol of German power in Carniola.38 In addition to the accusations that it had aligned with the German side, Slovenians reproached the Carniolan Savings Bank with ignoring the Slovenian institutions. This was one of the main reasons why, in the eyes of Slovenians, it continued to be seen as a German monetary institution.

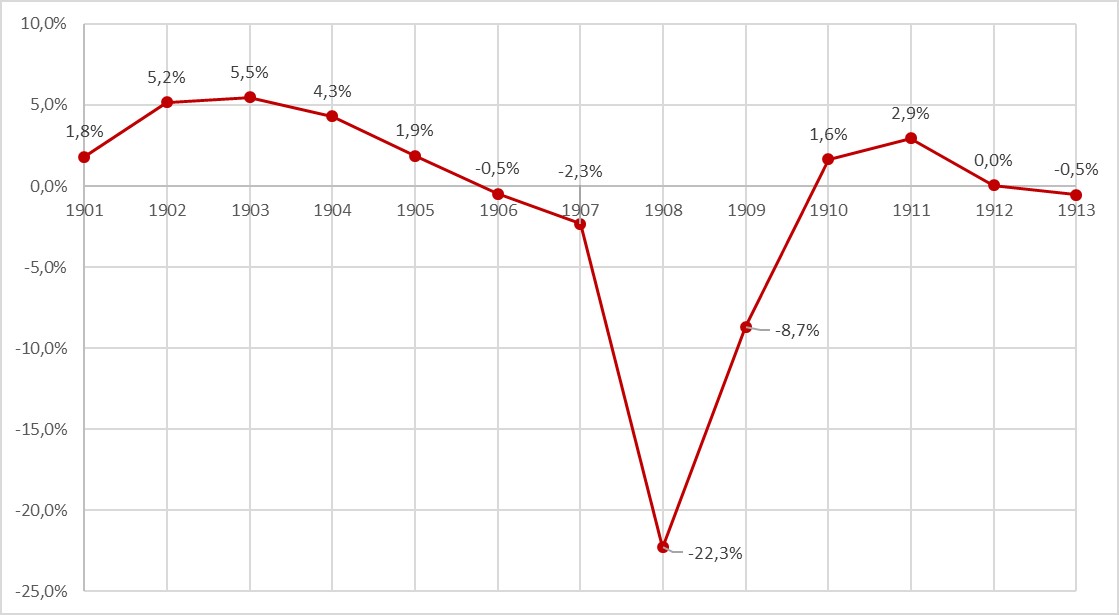

6Over the entire period from 1881 to 1914, the growth of deposits in almost all savings banks reached an annual average of 4 to 5 %, with the exception of few individual savings banks, among them, in 1908, the Carniolan Savings Bank. The overall development of savings banks was particularly favourable in the years between 1908 and 1910, when growth in the amount of 6 to 7 % was recorded.39 In 1908, the highest increase in deposits was recorded, amounting to K 316,594,440, which was 45.4 % more than the year before. In this year, almost 95 % of all savings banks in the Austrian part of the Monarchy recorded growth on the passive side of the balance sheet. The exception was the province of Carniola, where a decrease of about 4.5 % was recorded as a result of a run on the Carniolan Savings Bank in Ljubljana. Apart from the Carniolan Savings Bank, all other monetary institutions in Carniola showed an increase in deposits.40

5. The Bank Run and Boycott of the Carniolan Savings Bank in 1908 and 1909

1In the last decade before the outbreak of World War I, in an extremely tense political situation, Slovenian politicians decided to hinder the Carniolan Savings Bank’s activities. They encouraged massive savings withdrawals and undermined the confidence in the Bank’s credibility by spreading fabricated rumours of business irregularities and insolvency. After the German inscriptions had been removed from the shops, a resolute boycott of German merchants and the run on the Carniolan Savings Bank began. Many people, especially from the countryside, kept withdrawing their savings from the Carniolan Savings Bank day after day. 41 The main reason for this reaction was the Carniolan Savings Bank’s reputation as a German monetary institution.42 Its management dedicated an entire section of the 1908 annual report to the September events: “First, we must remember the rush, which occurred in September against our institution. […] For no reason, a dishonest, defamatory, and hostile attack on the leadership of our institution was initiated – an insult to the memory of men who had gained innocent merits for our land, and no one yet dared to take their honour and honesty. They argued that our institution was no longer safe. […] The instigators walked from house to house to scare our investors, claiming that they would lose all of their money in our institution.”43

2Slovenians were informed about “the bank run” by the liberal newspaper Slovenski narod, which openly called for a boycott of the Carniolan Savings Bank and encouraged a swift response of Slovenian depositors, who were to withdraw their savings. Therefore, on 26 September 1908, an article titled Važen gospodarski nasvet [Important Economic Advice] was published, emphasising the possibility of monetary losses due to withdrawals during the month. Furthermore, people could lose the right to collect interest rates. In the article, special attention was paid to Slovenian readers, who were warned that all Slovenian monetary institutions would be accepting account ledgers belonging to the Carniolan Savings Bank. These Slovenian institutions also offered the potential depositors to withdraw cash from the old account ledgers or to provide them with new account ledgers in the amount of their accounts at the Carniolan Savings Bank.44

3On 8 October 1908, the Carniolan Provincial Government published a report in the Laibacher Zeitung, signed by Count Ludovik Marquis de Gozani, Councillor and Provincial Commissioner of the Carniolan Savings Bank, and Janko Kremenšek, the Regional Government Councillor. The report discloses the findings of the audit that the Carniolan Savings Bank carried out pursuant to the law, and the savings deposits were as safe as possible. Any fear of losses was therefore unjustified and unfounded. 45 Naturally, the Carniolan Savings Bank was not happy that the official state institutions examined its business: it confirmed that it had not found any realistic reasons for the fear of the depositors, which had spread among the people.46 On 15 October 1908, the Slovenski narod newspaper published what was, according to the author, an expert article about the final account and the annual report of the Carniolan Savings Bank for the business year 1907. The author paid special attention to the audit, which was, in his opinion, completely inadequate. It was disputable that the authorities had only spent a single day on reviewing all of the Carniolan Savings Bank’s books. In addition, the author considered the official statement by the Government Commissioner of the Carniolan Savings Bank Count Gozani and the regional government official Kremenšek. Again, the time they had spent to prepare and write their reviews of the business books in the first half of 1908 was questionable and too short. Based on these arguments, the author of the article concluded that both the audit and the inspection carried out by government representatives were completely unprofessional. Most of all, he was disturbed by the fact that the review was not carried out by Slovenian experts.47

4On 20 October 1908, the management of the Carniolan Savings Bank convened an extraordinary session of the General Assembly of their Association because of the situation followed by the wave of accelerated deposit withdrawals. Ottomar Bamberg, the president of the Carniolan Savings Bank, informed the members of the delicate situation and the condition of the funds invested in the Savings Bank. Between 19 September and 19 October 1908, a million crowns had been deposited, while the Bank had been forced to pay out more than 6 million crowns, which meant that the amount of deposits had decreased by 7.5 % in a single month. To cover the difference, the Bank used cash, credits, and a portion of the state securities. Bamberg recalled all the previous crises and tried to reassure the members of the Association with the fact that even if the depositors took out all money, the Bank would still have a reserve fund of 9 million crowns at its disposal. He concluded his speech optimistically with the following words: “Excessive withdrawals have caused some inconvenience, but this is merely transient.”48

5The article that followed the extraordinary session of the General Assembly of the Carniolan Savings Bank Association, published in the Slovenski narod newspaper on 30 October 1908, underlined the following: “The Carniolan Savings Bank counts on the fact that the deposits would not be repaid and that the management knows how to handle the situation by employing certain new business tactics they deem appropriate.”49 The author of this comment devoted special attention to the Carniolan Savings Bank’s credit policy of mortgaging loans issued in Carniola. The problem arose as soon as the Savings Bank started cancelling this type of loans in the province of Carniola. In the author’s opinion, the Savings Bank violated the provisions of § 17 of its Regulations, according to which it was obligated to first collect all of the loans issued in other parts of the Monarchy. 50

6The money that the Carniolan Savings Bank had to pay out to its depositors between October 1908 and June 1909 far exceeded all of its available cash. Deposits had been in decline for several years. In addition, the sale of securities had not satisfied the growing demand. Therefore, the Savings Bank stopped approving new loans and started realising mortgages and municipal loans – not merely in Carniola, but in the other parts of the Monarchy as well. In order to secure money without compromising its reserve fund, the Savings Bank started selling its real estate.51

7Table 1. The mortgage loans of Carniolan Savings Bank from 1901 until 1913

| Year | Mortgage loans for the province of Carniola at a lower interest rate | Mortgage loans for the province of Carniola at the regular interest rate | Mortgage loans for other provinces | ||||||

| New loans | Refunded amount | At the end of year | New loans | Refunded amount | At the end of year | New loans | Refunded amount | At the end of year | |

| 1901 | 3,360 | 30,294 | 715,402 | 651,561 | 434,442 | 12,613,015 | 10,000 | 1,088,638 | 17,759,443 |

| 1902 | 2,650 | 38,286 | 639,766 | 1,100,581 | 600,193 | 13,233,609 | 1,893,007 | 845,274 | 18,807,178 |

| 1903 | 400 | 36,402 | 603,764 | 918,020 | 437,171 | 13,714,458 | 1,090,592 | 1,044,626 | 18,853,091 |

| 1904 | 1,600 | 26,995 | 578,369 | 907,026 | 490,367 | 14,131,117 | 5,523,000 | 2,387,799 | 21,988,340 |

| 1905 | 800 | 30,233 | 548,935 | 616,569 | 529,356 | 14,218,329 | 2,125,570 | 1,894,714 | 22,219,194 |

| 1906 | 2,600 | 32,194 | 519,341 | 1,429,118 | 802,606 | 14,844,840 | 1,622,974 | 1,328,927 | 22,513,242 |

| 1907 | 5,140 | 32,887 | 491,594 | 1,294,200 | 832,736 | 15,306,304 | 287,625 | 784,388 | 22,016,476 |

| 1908 | 300 | 31,577 | 460,316 | 730,333 | 644,617 | 15,392,020 | 19,000 | 1,680,469 | 20,355,004 |

| 1909 | 2,066 | 24,411 | 437,971 | 486,873 | 1,927,275 | 13,951,618 | 5,000 | 14,032,095 | 6,327,910 |

| 1910 | 2,000 | 16,960 | 423,011 | 1,169,187 | 462,659 | 14,658,146 | / | 896,196 | 5,431,713 |

| 1911 | 1,000 | 24,226 | 399,785 | 1,078,558 | 440,104 | 15,296,600 | / | 440,553 | 4,991,159 |

| 1912 | 1,000 | 15,516 | 385,268 | 689,760 | 517,835 | 15,468,525 | / | 326,781 | 4,664,378 |

| 1913 | 2,000 | 26,824 | 360,444 | 604,600 | 614,078 | 15,459,046 | / | 141,040 | 4,523,337 |

8Source: Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des Jahres 1901−1913

9The statistics indicate how successfully the Carniolan Savings Bank discharged obligations from debtors who lived outside Carniola. Table 1 shows the level of mortgage loans for the debtors from Carniola with the regular interest rate that remained at the same level in 1908 as in the previous years. A major change occurred in 1909, as the approved loans amounted to only 25 % of the discharged obligations. Although the level decreased by 9 % at the end of 1909, in the following years, fluctuations in this section were less frequent, since the Savings Bank granted more newly approved loans. At the end of the year, the balance reached the pre-crisis level. However, the amount of discharged obligations for all those who lived in the other parts of the Monarchy peaked in 1909, when 14 million crowns were paid to the Carniolan Savings Bank. At the end of the year, the amount reached only 31 % of the one from the previous year. During the next few years, the Carniolan Savings Bank did not approve new mortgage loans to people from the other parts of Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. 52

10One of the leaders of the struggle against the Carniolan Savings Bank was Ivan Hribar, who approved the scandalous articles in the Slovenski narod newspaper and submit the interpellation in the Imperial Council in December 1908.53 Hribar first spoke about the Carniolan Savings Bank in the Imperial Council on 4 December 1908. On this occasion, he submitted an interpellation against the head of the Ministry of Justice because of the retraction of articles and notices in the Slovenski narod newspaper, discussing various topics regarding the Carniolan Savings Bank. His speech was published in the same newspaper; while later, all the articles presented by him at the December session were published in a special brochure.54

11On the provincial level, Dr Ivan Oražen held speeches against the Savings Bank in the Carniolan Provincial Assembly in January 1909. A very heated debate developed at the seventh session of the Carniolan Provincial Assembly on 15 January 1909. Dr Ivan Oražen collected and presented all the arguments against the Savings Bank, mentioned until that moment. He spoke about the inadequate security of deposits and the reserve fund; the exchange rate loses because of the unsuitable real estate investment policy; and about the lack of government control over the business operations of the Carniolan Savings Bank. He was particularly disturbed by the distribution of its net income, mostly intended for German institutions and German national interests. Provincial President Baron Schwarz and Josef Schwegel spoke at the session as well. They defended the Carniolan Savings Bank and tried to justify its operations. 55

12Shortly thereafter, on 24 January 1909, Dr Oražen once again spoke about the Carniolan Savings Bank at a meeting in the Town Home in response to the Savings Bank representatives who had prepared comments on his exhaustive speech in the Carniolan Provincial Assembly. The management of the Carniolan Savings Bank published an article titled Erklärung (Explanation) in the Laibacher Zeitung56 newspaper, rejecting all accusations against the Savings Bank. Afterwards, the article was translated and published in the Slovenian language in a special brochure.57 In his speech in the Town Home, Dr Oražen once again listed all the complaints against the Savings Bank but did not present any new arguments. He therefore concluded the speech with the following words: “However, it remains unfortunate that the Carniolan Savings Bank is an association of 65 members, harmful to us and our political life.”58 The Slovenski narod newspaper published the speech on the following day, but it had to be retracted. The retraction of the article caused Ivan Hribar to submit a new interpellation at a session of the Imperial Council on 29 January 1909. The text of Oražen’s speech at the Town Home can also be found in the aforementioned brochure containing the articles that Ivan Hribar had submitted during the interpellation at the December session of the Imperial Council in 1908.59

1Source: Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr (1901−1913)

13The following months were more peaceful: even the Slovenski narod newspaper refrained from publishing any more articles analysing the business operations of the Carniolan Savings Bank. It did not write about the Carniolan Savings Bank again until after its regular General Assembly session of 15 April 1909. The newspapers containing the article discussing the annual report of Carniolan Savings Bank were retracted, which resulted in Ivan Hribar’s new interpellation against the Minister of Justice. At the April session, the Savings Bank’s management adopted the annual report and final annual account for the business year of 1908. In his report, President Bamberg mentioned that the amount of money invested in the Savings Bank had decreased to 52,656,217 crowns at the end of 1908, which was 22.27 % less in comparison with the previous year. He tried to improve the morale with the fact that accelerated withdrawals had actually increased the security of savings of the depositors who had not withdrawn their money from the Savings Bank. Furthermore, he pointed out that the reserve fund had remained untouched.60

6. The Impact of the Bank Run and Boycott on the Business of the Carniolan Savings Bank

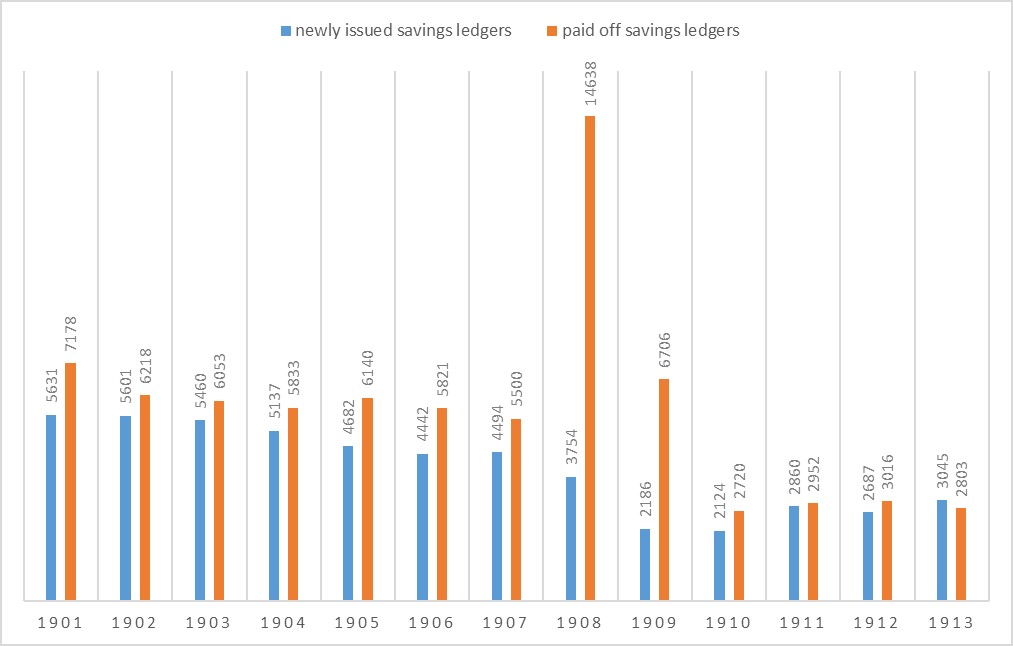

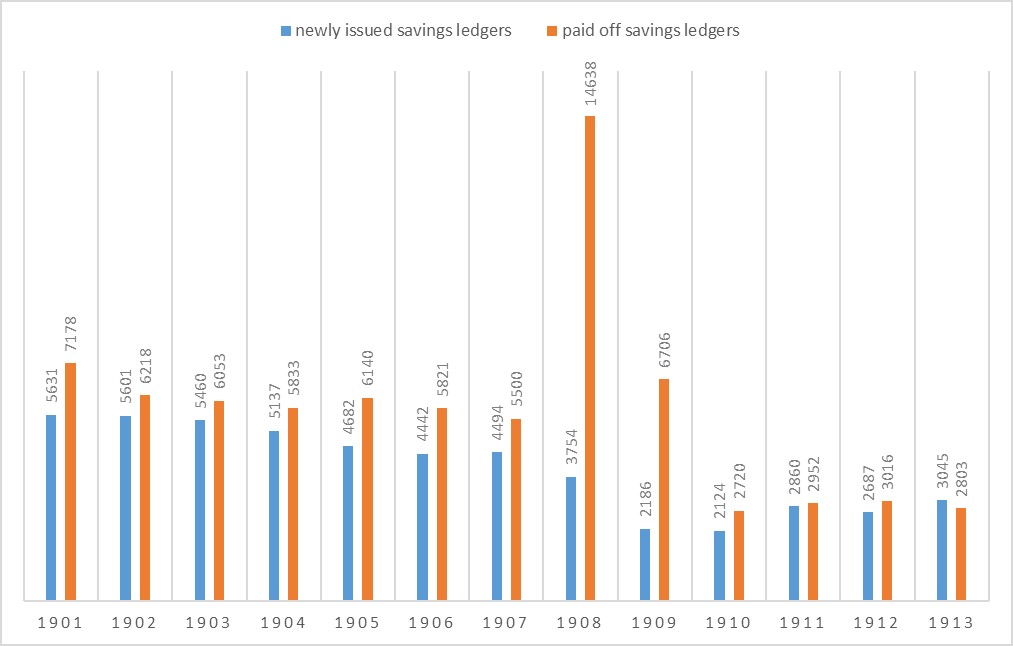

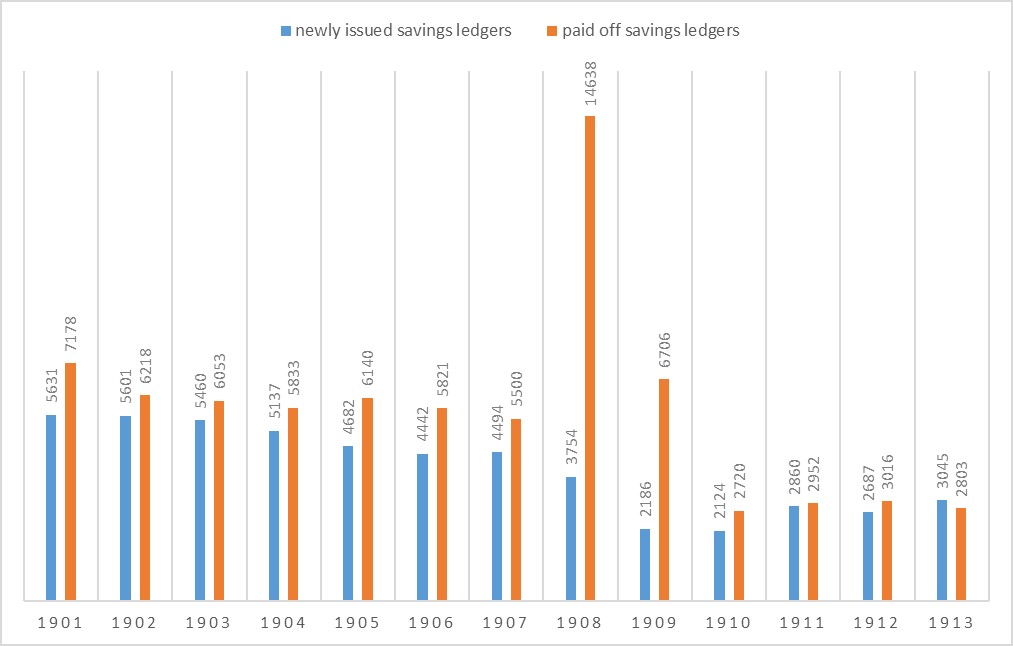

1The chart showing the comparison of the number of newly issued and paid off savings booklets best illustrates the bank run and boycott of the Carniolan Savings Bank. Although the number of newly issued booklets had been declining since the beginning of the 20th century, the biggest difference occurred in 1908, followed by 1909, when the number of paid off savings booklets far exceeded that of the newly issued ones.

1Source: Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr (1901−1913)

2Although the decline in the number of newly issued account ledgers in the case of the Carniolan Savings Bank is a good indicator of the influence of the bank run and boycott of 1908 and 1909 on the Savings Bank’s operations, the trend of the number of account ledgers is not necessarily an indicator of a decrease of money invested in a savings bank. During the period under consideration, there were 12 regulatory savings banks operating in the province of Carniola. In addition to the Carniolan Savings Bank, two more had fewer newly issued savings ledgers than the liquidated ones in 1908 and 1909. The Kočevje Savings Bank had 37 more closed accounts, and yet this had no effect on the amount of the received deposits. In the Kranj Savings Bank, the number of closed deposit accounts exceeded that of newly opened ones by 289 and the bank in question received less money from depositors, but the deficit was covered with capitalised interests.61

1Source: Source: Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1908

3The 1908 official statistical report of the Austrian Statistical Office discussed the deposit increases and decreases in Carniola specifically. The report also includes a spreadsheet listing, on the one hand, all savings banks in the province of Carniola with a positive balance between received and paid out money; and, on the other hand, the Carniolan Savings Bank. The Carniolan Savings Bank experienced a loss of more than 15 million crowns or 22.27 %, while the other savings banks in that province recorded an increase in deposits of more than 10 million crowns or 22.42 %.62 The author of the report emphasised that the level of deposits in Carniola, decreased by more than 5 million crowns or 4.46 %, had resulted from the run on the Carniolan Savings Bank.63

4The management of the Carniolan Savings Bank found that investing in mortgage loans was no longer profitable. Moreover, this money was less liquid and did not provide security during unpredictable events. The management was aware that the Savings Bank needed to invest an adequate part of its deposits in simple and highly liquid assets. At the extraordinary meeting of the General Assembly of the society of the Carniolan Savings Bank on 20 October 1908, President Bamberg discussed the solutions in case of new attacks. He suggested the following: “Changes in business policy are necessary; we need to take care of greater investments in goods because our investments in real estate exceeded the usual 60 % and reached 63 %. We have to reduce mortgage loans.”64 For these reasons, the Savings Bank decided to change its investment policy. As the chart shows, the Savings Bank prioritised investments in government securities, which exceeded the mortgage credit investments.

1Source: Source: Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des Jahres 1901−1913

5In order to secure money without compromising its reserve fund, the Carniolan Savings Bank started selling its real estate. It sold the building of the old shooting range in Ljubljana in 1910, while in the following year, it sold its houses in Trieste.65 At the regular General Assembly on 29 June 1909, it adopted the decision to increase the deposit interest rate from 4 % to 4.5 %. The aim of this measure was to attract as many new depositors as possible. Notwithstanding, the measure did not achieve much success because it other financial institutions soon followed suit, including the Carniolan Savings Bank’s biggest competitor: the Ljubljana City Savings Bank.66

6The liquidation of the Carniolan Savings Bank’s pawnshop was a measure taken by the Savings Bank as a response to the boycott in 1908 and 1909. The decision to dissolve it was adopted at an extraordinary General Assembly session of 20 October 1908.67 During its existence, the Carniolan Savings Bank established several institutions with various charitable purposes. The first of these was a pawnshop, which started operating in 1835. This institution functioned until 1910 when it was finally liquidated as a consequence of the 1908 boycott. The pawnshop had opened for business on 4 November 1835, on the 15th anniversary of the Carniolan Savings Bank. The Savings Bank had unused money that remained in the cash register. Therefore, the management decided to use that money to establish a special pawnshop. The purpose of this institution was to act for the public good, especially for the benefit of the poorest inhabitants of Carniola.68 The pawnshops, financed by savings banks, enabled the most deprived to escape the clutches of moneylenders to whom they paid exorbitant interest rates.69 During the first years of its operation, the pawnshop showed a considerable annual turnover. For this reason and because it protected people from usury, it quickly became popular among the poorer social strata. Nevertheless, the expectations of the Savings Banks’ management that the loans they gave to the pawnshop would turn a profit were not fulfilled. The expenditures of the pawnshop exceeded its income, and the Savings Bank had to cover this loss from its own income.70 The pawnshop operated with loss until 1896, and then started showing a slight profit as of 1897. The profit was very modest and insufficient to cover employee salaries.71 As of 1 December 1908, the pawnshop no longer accepted items, and the liquidation of this institution was completed on 1 January 1910.72 The response of the Slovenski narod newspaper to the decision of the Carniolan Savings Bank to close the pawnshop was very negative. The article published on 25 May 1909 stated the following: “The Carniolan Savings Bank eliminated the pawnshop simply to prevent the people who had broken the windows of the institution’s building from getting anything from it.”73 The Ljubljana Municipal Council established its own pawnshop, which opened on 1 December 1909 as a response to this move of the Carniolan Savings Bank.74

7Every year, the Carniolan Savings Bank would dedicate a certain amount to various institutions from its net profit. In the very tough circumstances, the peak of the September 1908 events brought a significant change. Under pressure, the Savings Bank decided to only donate money to those who remained loyal to it.75 However, the donations were only reduced in 1909, which was a direct consequence of the boycott. In the next year, they returned to the pre-crisis levels. Nevertheless, in the following years, the Carniolan Savings Bank provided the highest support to German institutions such as the Philharmonic Society in Ljubljana, the Theaterverein, the German kindergartens in Ljubljana, Tržič, Zagorje, and Kočevje, and to the Kranj section of the German Mountain Society.76

8At the General Assembly on 30 December 1909, the management of the Society of the Carniolan Savings Bank made a decision to change the inscription on the building: since then, it was in the Slovenian language. Moreover, it started publishing its annual reports in the Slovenian language. Nevertheless, this financial institution was still considered as the German financial pillar in the province of Carniola and would continue to be seen as such until the very disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1918.77

7. Conclusion

1The Carniolan Savings Bank found itself entangled in the Slovenian-German conflicts. It had to deal with considerable pressures as well as an extensive run on its deposits after the national struggles had culminated in September 1908. The 1908 crisis was a local phenomenon in the province of Carniola, starting with the news of the Carniolan Savings Bank’s insolvency. Bank runs were a common feature of crises and played a prominent role in monetary history: deposit withdrawals were a common reaction of the population during the periods of insecurity. The Carniolan Savings Bank strived to restore the trust of its clients while at the same time attempting to hedge its deposits in times of high risk. Based on its rulebook, a savings bank could refuse to pay out higher amounts; however, the Carniolan Savings Bank always tried to be consistent and satisfy all the demands of its depositors. It wanted to ensure the security of its business and invested money.

2With the September events and the subsequent boycott affecting the operations of the Carniolan Savings Bank, 1908 was a turning point in many aspects. Although the management of this financial institution tried to be more accessible for the Slovenian part of the population by publishing materials in the Slovenian language, the institution was nevertheless closed on several levels. This was confirmed with the orientation of its charitable activities only to “those who remained loyal to them” and did not encroach on the money invested in the Savings Bank. Still, the Carniolan Savings Bank retained its leading position in Carniola in almost all business segments, especially regarding the investments in government securities and the high amount of its reserve fund. On the other hand, the Ljubljana City Savings Bank got closer with the money gained from the depositors, while the City municipality opened its own pawnshop. However, it is very difficult to estimate how much damage the Carniolan Savings Bank actually suffered in the long term. The numbers confirm that it recovered very quickly after the massive withdrawals had stopped in the second half of 1909. Nevertheless, only a few years afterwards – in 1912 and 1913 – a new crisis started in the Balkans, while World War I, in particular, brought new challenges and even more radical changes.

Literature and Sources

- SI AS, Arhiv Republike Slovenije / Archive of Republic Slovenia:

- SI AS 437 − Hranilnica Dravske banovine.

- SI_ZAL_LJU, Zgodovinski arhiv Ljubljana / Historical Archive Ljubljana:

- SI_ZAL_LJU/0362 − Zbirka muzeja denarnih zavodov Slovenije, Ljubljana (1873−1966).

- Brubaker, Rogers. Ethnicity without groups. Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Brusatti, Alois. Die Habsburgischermonarchie 1848−1918, Bd 1, Die Wirtschaftliche Entwicklung. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1973.

- Calomiris, Charles W. and Gorton, Gary. “The Origins of Banking Panics: Models, Facts, and Bank Regulation.” In: Financial Markets and Financial Crises, ed. Glenn R. Hubbard, 109−74. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 1991. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d9d7/bf9c964fd2c1e2ea2828bb8805861ffe4425.pdf?_ga=2.174581930.988668068.1571398679-579497628.1571398679.

- Comin, Francisco. “Historical roots of the social commitment of savings banks in Spain − From charity to corporate social responsibility (1835−2002). 9th European Symposium on Savings Banks History, European Savings Banks: From Social Commitment to Corporate Social Responsibility, Madrid 4−5 May 2006.” Perspectives, No. 55 (2007): 27−33. Available at: https://www.wsbi-esbg.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Perspectives%2055.pdf.

- Cvirn, Janez. “Nemško gledanje na Slovence (1848−1914).” In: Sosed v ogledalu soseda. Od 1848 do danes, ed. Franc Rozman, 55−77. Ljubljana: Nacionalni komite za zgodovinske vede Republike Slovenije, 1995.

- Dirningen, Cristian. “Historic dimension of corporate social responsibility (CSR) of savings banks − the Austrian example. 9th European Symposium on Savings Banks History, European Savings Banks: From Social Commitment to Corporate Social Responsibility, Madrid 4−5 May 2006.” Perspectives, No. 55 (2007): 9–18. Available at: https://www.wsbi-esbg.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Perspectives%2055.pdf.

- Fritz, Hedwig. 150 Jahre Sparkassen in Österreich. Geschichte. Wien: Sparkassenverl, 1972.

- Judson, Pieter M. The Habsburg Empire. A New History. Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2016.

- Lazarević, Žarko. Plasti prostora in časa. Iz gospodarske zgodovine Slovenije prve polovice 20. stoletja. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2009.

- Lazarević, Žarko and Prinčič, Jože. Bančniki v ogledalu časa. Življenjske poti slovenskih bančnikov v 19. in 20. stoletju. Ljubljana: ZBS Združenje bank Slovenije, 2005.

- Matić, Dragan. Nemci v Ljubljani 1848−1918. Ljubljana: Oddelek za zgodovino Filozofske fakultete, 2002.

- Matjašič, Marjan. “Stališče vojaških oblasti do nemirov septembra 1908 v Ljubljani.” In: Kronika, 32, No. 1 (1984): 28–35.

- Melik, Vasilij “Politične razmere na Štajerskem v času Napotnika.” In: Slovenci 1848−1918. Razprave in članki, 608−20. Maribor: Litera 2002.

- Melik, Vasilij. “Problemi slovenske družbe 1897-1914.” In: Slovenci 1848−1918. Razprave in članki, 600−07. Maribor: Litera 2002.

- Sandgruber, Roman. Ökonomie und Politik. Österreichische Wirtschaftsgeschichte vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Wien: Ueberreuter, 1995.

- “Septembrski dogodki.” In: Ilustrirana zgodovina Slovencev, ed. Marko Vidic, 282. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1999.

- Studen, Andrej. “Protinemški izgredi v Ljubljani leta 1903.” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino, 38, No. 1−2 (1998): 15−21.

- Thol, Carolin. Poverty relief and financial inclusion. Savings banks in nineteenth century Germany. Brussels: WSBI−ESBG The Voice of Savings and Retail Banking, 2016. Available at: https://www.wsbi-esbg.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/8119_ESBG_BRO_STUDY.pdf.

- Wurm, Susanne. “The Development of Austrian Financial Institutions in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. Comparative European Economic History Studies.” Working Paper Series, No. 31 (2006): 7−72. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.527.9024&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Zahra, Tara. “Imagined Noncommunities: National Indifference as a Category of Analysis.” Slavic Review, 69, No. 1 (spring 2010): 93−119. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313457649_Imagined_Noncommunities_National_Indifference_as_a_Category_of_Analysis.

- Laibacher Zeitung, 1908, 1909.

- Slovenski narod, 1908, 1909.

- Hribar, Ivan. Kranjska hranilnica. Ljubljana: Narodna Tiskarna, 1909.

- Hribar, Ivan. Moji spomini. Od 1853. do 1910. leta, I. Ljubljana: 1928.

- Jeglič, Anton Bonaventura. Jegličev dnevnik, znanstvenokritična izdaja. Eds. Blaž Otrin and Marija Čipić Rehar. Celje: Celjska Mohorjeva družba, 2015.

- Kranjska hranilnica v Ljubljani v letu 1908. Ljubljana: Kleinmayr & Bamberg, 1909.

- Kranjska hranilnica v Ljubljani v letu 1909. Ljubljana: Kleinmayr & Bamberg, 1910.

- Kranjska hranilnica v Ljubljani v letu 1910. Ljubljana: Kleinmayr & Bamberg, 1911.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1901. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1902.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1902. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1903.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1903. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1904.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1904. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1905.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1905. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1906.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1906. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1907.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1907. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1908.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1908. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1909.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1909. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1910.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1910. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1911.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1911. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1912.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1912. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1913.

- Rechnungs–Abschluss der krainischen Sparkasse des mit derselben vereinigten Pfandamtes und Creditvereins am Schlusse des Jahres 1913. Laibach: Verlag der krainischen Sparkasse, 1914.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1901. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentral–Kommision. LXX Band, 2. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1903.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1902. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentral–Kommision. LXXII. Band, 2. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1905.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1903. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentral–Kommision. LXXVI. Band, 2. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1905.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1904. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentral–Kommision. LXXX. Band, 1. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1906.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1905. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentral–Kommision. LXXXII. Band, 2. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1907.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1906. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentral–Kommision. LXXXVI. Band, 4. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1909.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1907. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentralkommision. LXXXVIII. Band, 4. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1910.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1908. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentralkommision. XCI. Band, 3. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1911.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1909. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentralkommision. XCIII. Band, 2. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1912.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1910. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentralkommision. 7. Band, 2. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1912.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1911. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentralkommision. 10. Band, 1. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1913.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1912. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentralkommision. 12. Band, 2. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1915.

- Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1913. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentralkommision. 15. Band, 1. Heft. Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1916.

- Stenografični zapisnik sedme seje deželnega zbora kranjskega v Ljubljani dne 15. januarja 1909. Available at: https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:doc-UUJMEUO1/590bbe26-3404-4471-833e-6111ceabb8b2/PDF.

- V pojasnilo. Ljubljana: Kleinmayr & Bamberg, 1909.

Nataša Henig Miščič

KRANJSKA HRANILNICA IN SLOVENSKO-NEMŠKI ODNOSI LETA 1908 IN 1909

POVZETEK

1Kranjska hranilnica se je znašla v neprijetnem položaju, vpletena v konflikte slovenskega in nemškega narodnega gibanja, ter se je bila primorana spoprijeti z velikim političnim in gospodarskim pritiskom. Potem ko so v drugi polovici septembra leta 1908 napetosti dosegle vrhunec, se je soočala z večmesečnim navalom, ki je terjal visoke zneske izplačanega denarja iz hranilnice. Kriza v letu 1908 je lokalni pojav na Kranjskem, začela pa se je z novico o insolventnosti Kranjske hranilnice. Množično dvigovanje denarja iz finančnih zavodov je bil zelo pogost pojav v različnih krizah in predstavlja logičen odziv prebivalstva v času negotovosti. Slovenski politiki so v izjemno napetih političnih razmerah spodbujali množičen umik prihrankov in se na vsak način trudili spodkopati zaupanje v verodostojnost hranilnice s širjenjem neresničnih govoric o poslovnih nepravilnostih in insolventnosti. Slovenski vlagatelji so množično dvigovali svoje prihranke tudi zaradi nemškega predznaka Kranjske hranilnice. Hranilne vloge, ki jih je hranilnica izplačala svojim vložnikom med oktobrom 1908 in junijem 1909, so daleč presegale vso njeno razpoložljivo gotovino. Hranilnica je začela prodajati svoje vrednostne papirje, ampak to ni zadoščalo naraščajočim zahtevam. Zato je prekinila izdajo novih hipotekarnih kreditov in začela realizacijo posojil, ne le v deželi, ampak tudi v drugih delih monarhije. Kljub temu da je hranilnica leta 1909 zamenjala napis na svoji stavbi, ki je bil od takrat naprej v slovenskem jeziku, je še naprej veljala za nemški finančni steber na Kranjskem. Ta status je obdržala vse do konca obstoja avstro-ogrske monarhije leta 1918. V tem obdobju se ji je po višini vloženega denarja, ki ga je pridobila od vlagateljev, postopoma približevala Mestna hranilnica ljubljanska, ki je leta 1909 odprla tudi svoje Kreditno društvo in finančno pripomogla k ustanovitvi nove mestne zastavljalnice. Kranjska hranilnica je kljub vsemu obdržala vodilni položaj na Kranjskem v skoraj vseh poslovnih segmentih, zlasti pri naložbah v državne vrednostne papirje in visokih zneskih rezervnega sklada. Bila je osrednji finančni zavod v pokrajini in zelo pomemben dejavnik gospodarskega razvoja. Zato ni bilo nepomembno, kdo je imel nadzor nad njenim delovanjem.

* M.Sc., junior researcher, Institute of Contemporary History, Privoz 11, SI-1000 Ljubljana, natasa.henig@inz.si

1. For further information about the concept of national indifference, see Rogers Brubaker, Ethnicity without Groups (Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press, 2006). 12. Tara Zahra, “Imagined Noncommunities: National Indifference as a Category of Analysis,” Slavic Review, 69, No. 1 (spring 2010): 98–99.

2. SI_ZAL_LJU/0362, f. 18, Statuten und Geschäftsordnung der krainischen Sparkasse in Laibach, 24 December 1867, 2. More about organisations and ethnic groups in: Brubaker, Ethnicity without groups, 16.

3. Carolin Thol, Poverty Relief and Financial Inclusion. Savings Banks in Nineteenth Century Germany (Brussels: WSBI−ESBG The Voice of Savings and Retail Banking, 2016), 18, available at: https://www.wsbi-esbg.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/8119_ESBG_BRO_STUDY.pdf. Cristian Dirningen, “Historic Dimension of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) of Savings Banks − the Austrian Example,” the 9th European Symposium on Savings Banks History, European Savings Banks: From Social Commitment to Corporate Social Responsibility, Madrid 4−5 May 2006. Perspectives, 55, 2007, 12–13, available at: https://www.wsbi-esbg.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Perspectives%2055.pdf.

4. Charles W Calomiris and Gary Gorton, “The Origins of Banking Panics: Models, Facts, and Bank Regulation,” in: Financial Markets and Financial Crises, ed. Glenn R. Hubbard (Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 1991), 111−15, available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d9d7/bf9c964fd2c1e2ea2828bb8805861ffe4425.pdf?_ga=2.174581930.988668068.1571398679-579497628.1571398679.

5. SI AS 437, f. 38, Zgodovina hranilnice od 1909 do 1918, 1.

6. For further information, see Pieter M. Judson, The Habsburg Empire. A New History (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2016), 9−11.

7. Andrej Pančur, “Nacionalni spori,” in: Slovenska novejša zgodovina. Od programa Zedinjena Slovenija do mednarodnega priznanja Republike Slovenije: 1848−1992, I, ed. Jasna Fischer et al. (Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2005), 36.

8. See also Judson, The Habsburg Empire, 299−300.

9. Vasilij Melik, “Politične razmere na Štajerskem v času Napotnika,” in: Slovenci 1848−1918. Razprave in članki (Maribor: Litera, 2002), 608.

10. Ibid., 608, 609. Pančur, “Nacionalni spori,” 37.

11. Janez Cvirn, “Nemško gledanje na Slovence (1848–1914),” in: Sosed v ogledalu soseda. Od 1848 do danes, ed. Franc Rozman (Ljubljana: Nacionalni komite za zgodovinske vede Republike Slovenije, 1995), 55, 58–60.

12. Ibid., 60–61.

13. Pančur, “Nacionalni spori,” 38. Andrej Studen, “Protinemški izgredi v Ljubljani leta 1903,” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino, 38, No. 1–2 (1998): 15, 20.

14. Vasilij Melik, “Problemi slovenske družbe 1897–1914,” in: Slovenci 1848–1918. Razprave in članki (Maribor: Litera, 2002), 601.

15. Branko Goropevšek, “Odmev in pomen septembrskih dogodkov leta 1908. Spomin na 90-letnico dogodkov,” in: Slovenija 1848−1998. Iskanje lastne poti, eds. Stane Granda and Barbara Šatej (Ljubljana: Zveza zgodovinskih društev Slovenije, 1998), 115−16.

16. Ibid., 116–18.

17. “Septembrski dogodki,” in: Ilustrirana zgodovina Slovencev, ed. Marko Vidic (Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1999), 282. Pančur, “Nacionalni spori,” 38.

18. Ivan Hribar, Moji spomini. Od 1853. do 1910. leta, I (Ljubljana, 1928), 342.

19. Ibid., 346.

20. Anton Bonaventura Jeglič, Jegličev dnevnik, znanstvenokritična izdaja, eds. Blaž Otrin and Marija Čipić Rehar (Celje: Celjska Mohorjeva družba, 2015), 425−26.

21. Ibid.

22. Anton Bonaventura Jeglič, “Vernikom ljubljanske škofije,” Škofijski list, No. 8 (1908), 115.

23. Fran Šuklje, Iz mojih spominov, II. (Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 1995), 202.

24. “Samoslovenske napise,” Slovenski narod, 21 September 1908, 1.

25. Dragan Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani 1848−1918 (Ljubljana: Oddelek za zgodovino Filozofske fakultete, 2002), 347−48.

26. “Gibanje za gospodarsko osamosvoto,” Slovenski narod, 28 September 1908, 2.

27. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 354.

28. Marjan Matjašič, “Stališče vojaških oblasti do nemirov septembra 1908 v Ljubljani,” Kronika, 32, No. 1 (1984): 31

29. Goropevšek, “Odmev in pomen,” 120.

30. Hedwig Fritz, 150 Jahre Sparkassen in Österreich. Geschichte (Wien: Sparkassenverl., 1972), 482−84.

31. In Carniola, this process started somewhat later, during the 1870s. − Žarko Lazarević and Jože Prinčič, Bančniki v ogledalu časa. Življenjske poti slovenskih bančnikov v 19. in 20. stoletju (Ljubljana: ZBS Združenje bank Slovenije, 2005), 41−42.

32. Fritz, 150 Jahre, 485−86.

33. Alois Brusatti, Die Habsburgischermonarchie 1848−1918, Bd 1, Die Wirtschaftliche Entwicklung (Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1973), 363.

34. Roman Sandgruber, Ökonomie und Politik. Österreichische Wirtschaftsgeschichte vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart (Wien: Ueberreuter, 1995), 293, 311.

35. Susanne Wurm, “The Development of Austrian Financial Institutions in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. Comparative European Economic History Studies,” Working Paper Series, No. 31 (2006): 21, available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.527.9024&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

36. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 349.

37. Žarko Lazarević, Plasti prostora in časa. Iz gospodarske zgodovine Slovenije prve polovice 20. stoletja (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2009), 315.

38. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 349. Lazarević and Prinčič, Bančniki v ogledalu časa, 41−42.

39. Fritz, 150 Jahre, 486.

40. Statistik der Sparkassen in den im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreichen und Ländern für das Jahr 1908. Bearbeitet von dem Bureau der K. K. Statistischen Zentralkommision. XCI. Band, 3. Heft (Wien: Aus der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- und Staatsdrukerei, 1911), XXVII−XXVIII.

41. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 439. Lazarević and Prinčič, Bančniki v ogledalu časa, 41−42.

42. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 347.

43. Kranjska hranilnica v letu 1908 (Ljubljana: Kleinmayr & Bamberg, 1909).

44. “Važen gospodarski nasvet,” Slovenski narod, 26 September 1908, No. 225, 4.

45. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 349.

46. Lazarević and Prinčič, Bančniki v ogledalu časa, 42.

47. “Kranjska hranilnica,” Slovenski narod, 15 October 1908, 1.

48. SI AS 437, f. 10, Ottomar Bamberg, Geehrte Generalversammlung!, 20 October 1908, 1, 2. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 352.

49. “Kranjska hranilnica,” Slovenski narod, 30 October 1908, 1.

50. Ibid.

51. SI AS 437, f. 38 Zgodovina hranilnice od 1909 do 1918, 1.

52. Kranjska hranilnica v Ljubljani v letu 1909 (Ljubljana: Kleinmayr & Bamberg, 1910).

53. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 352.

54. Ivan Hribar, Kranjska hranilnica (Ljubljana: Narodna Tiskarna, 1909), 1−23.

55. Stenografični zapisnik sedme seje deželnega zbora kranjskega v Ljubljani dne 15. januarja 1909, 199, 201–04, available at: https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:doc-UUJMEUO1/590bbe26-3404-4471-833e-6111ceabb8b2/PDF.

56. “Erklärung,” Laibacher Zeitung, 22 January 1909, 147−48.

57. V pojasnilo (Ljubljana: Kleinmayr & Bamberg, 1909), 1−8.

58. Hribar, Kranjska hranilnica, 40.

59. Ibid., 36−40.

60. Kranjska hranilnica v letu 1908. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 353.

61. Statistik der Sparkassen für das Jahr 1908, 6, 22.

62. Ibid., XXVII.

63. Ibid.

64. SI AS 437, f. 10, Ottomar Bamberg, “Geehrte Generalversammlung!” 20 October 1908, 3.

65. SI AS 437, f. 38, Zgodovina hranilnice od 1909 do 1918, 1, 2.

66. Kranjska hranilnica v Ljubljani v letu 1909. AS 437, f. 38, Zgodovina hranilnice od 1909 do 1918, 1, 2.

67. “Auflassung des Pfandamtes der Krainische Sparkasse,” Laibacher Zeitung, 7 November 1908, 2358.

68. SI AS 437, f. 38, Ustanovitev Kranjske hranilnice, 11, 12.

69. Francisco Comin, “Historical Roots of the Social Commitment of Savings Banks in Spain − From Charity to Corporate Social Responsibility (1835−2002). The 9th European Symposium on Savings Banks History, European Savings Banks: From Social Commitment to Corporate Social Responsibility, Madrid 4−5 May 2006,” Perspectives, No. 55 (2007): 29, available at: https://www.wsbi-esbg.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Perspectives%2055.pdf.

70. Kranjska hranilnica v Ljubljani 1910 (Ljubljana: Kleinmayr & Bamberg 1911).

71. SI AS 437, f. 10, Ausserordentliche Generalversammlung vom 20. Oktober 1908, No. 3989, Antrag wegen Auflassung des Pfandamts.

72. SI AS 437, f. 38, Zgodovina hranilnice od 1909 do 1918, 3.

73. “Renitetna hranilnica,” Slovenski narod, 25 May 1909, 2.

74. “Ljubljanski občinski svet. Poročila personalnega in pravnega odseka,” Slovenski narod, 21 July 1909, 3. “Ljubljanski občinski svet. Mestna zastavljalnica,” Slovenski narod, 9 December 1909, 2.

75. Kranjska hranilnica v Ljubljani v letu 1908.

76. SI AS 437, f. 38, Zgodovina hranilnice od 1909 do 1918, 3, 4.

77. Ibid., 5.