The Linguistic Landscape of Lower Styria on Picture Postcards (1890-1920)

UDC: 323.1:81'246.2:77.047(497.4:436)"1890/1920"

JEZIKOVNA KRAJINA SPODNJE ŠTAJERSKE NA RAZGLEDNICAH (1890–1920)

IZVLEČEK

1Ob koncu devetnajstega stoletja je v večjezični Habsburški monarhiji jezik postal pomemben – če ne kar najpomembnejši – etnični označevalec pri oblikovanju različnih nacionalnih identitet. V jezikovno mešanih pokrajinah monarhije jezik ni več veljal le za preprosto orodje komunikacije, ki ga je mogoče pragmatično izbirati glede na govorne okoliščine, ampak je postal simbol nacionalne identitete. Koliko pa je res znanega o dejanski uporabi jezika v dvojezičnih pokrajinah? S primerom dvojezične slovensko-nemške pokrajine Spodnje Štajerske je v prispevku predstavljeno, kako lahko razglednice kot bogat vir, ki je na voljo v velikih količinah, pomagajo osvetliti navzočnost jezika oziroma jezikov v javni sferi, družbeno stratifikacijo in geografsko porazdelitev jezikov, jezik v formalni in neformalni komunikaciji ter različne vrste dvojezičnosti in jezikovnega stika. Preučevanje razglednic s preloma stoletja – sredstva, ki je del vsakdanjega življenja – nam torej omogoči vpogled v jezikovno krajino Spodnje Štajerske in naslika podobo pokrajine, za katero niso bili značilni samo nacionalni konflikti, ampak tudi miren soobstoj.

2Ključne besede: Spodnja Štajerska, razglednice, zgodovina vsakdanjega življenja, dvojezičnost, jezikovni stik

ABSTRACT

1Towards the end of the nineteenth century in the multilingual Habsburg Empire, language became an important – if not the most essential – ethnic marker in the construction of different national identities. In the linguistically mixed regions of the Empire, language was no longer perceived merely as a tool for communication that could be chosen pragmatically, depending on the social situations, and instead became an emblem of one’s national identity. However, how much is really known about how language was actually used in bilingual regions? By using the example of the bilingual Slovenian/German-speaking region of Lower Styria (Spodnja Štajerska/Untersteiermark), this paper suggests that picture postcards – a rich source available in large quantities – can help shed light on the visibility of language(s) in the public sphere, the social stratification and geographic distribution of languages, the language of formal and informal communication, as well as on the various forms of bilingualism and language contact. In short, the examination of picture postcards from the turn of the century, a medium close to everyday life, yields insights into the linguistic landscape of Lower Styria and paints a picture of a region characterised not only by national conflicts but also peaceful coexistence.

2Keywords: Lower Styria, picture postcards, history of everyday life, bilingualism, language contact

1. Introduction

1Picture postcards were the first truly mass medium of communication. Even though they were long overlooked by historians as a seemingly “banal” source of information, after the “pictorial turn” 1 they have no longer been conceptualised as passive representations but rather as media apparatuses that condition the viewer’s patterns of perception. Postcards are multimodal specimens, characterised by an intersection of visual and textual information, and should be studied not only as visual items but also as linguistic ones. 2 Precisely because of this multimodal character, postcards are nowadays of great historical interest. They are now appreciated as a mass medium close to everyday life, which can help tell a different story than other traditional sources. For instance, in this case, they are a vital source of information about language distribution, language contact, the prevailing (albeit asymmetrical) bilingualism, and the coexistence of the Slovenian and German languages in Lower Styria. The predominant topographical views of places, regions, and tourist attractions were framed primarily with German captions as well as Slovenian and bilingual captions by various producers and personalised with handwritten elements by their individual senders. Language in the public sphere is documented by the postcard photographs through elements like commercial signs on storefronts and business institutions. Postcards thus served as a sort of a stage on which the claims to the shared territory could be presented visually and textually, and where traces of language are evident in many different forms. They constitute an opportunity to portray the “linguistic landscape” 3 of a historical region by providing relevant information about the relative power and status of the competing languages. This paper aims to portray this linguistic landscape in Lower Styria during the period between 1890 and 1920. The general observations about the history of the medium and the methodological challenges and advantages of working with postcards will first be discussed, followed by examples of the multi-layered information extracted from postcards. These observations are based on the results of a three-year research project on postcards from Lower Styria, conducted at the University of Graz, which will also be discussed.

2. Postcarding Lower Styria

1Lower Styria (Špodnja Štajerska/Untersteiermark), the southern part of the crown land of Styria and one of the bilingual regions of the Monarchy, was characterised by the peaceful albeit asymmetrical coexistence of the German and Slovenian languages well into the second half of the nineteenth century. 4 German had certain advantages over Slovenian: it had been codified earlier than Slovenian; it was the dominant language in the urban areas; and it was considered to be the language of the upper class and higher education. Given that in most cases, social advancement was connected to acculturation, a good command of German was, above all, economically relevant for Slovenian families. Bilingualism and “extended diglossia” 5 was therefore widespread, especially among the educated Slovenian elite. German was predominantly used in the public discourse in the towns of Lower Styria, which were the centres of trade, higher education, and political power, while Slovenian was much more common in the rural areas. While this bilingual situation in Lower Styria remained mostly indifferent to the national identity and remained – despite the beginnings of nationalist movements – without friction well into the 1860s, things changed in the 1870s and the 1880s. The politics of identity, which kept pushing the nationalist concept of homogeneous linguistic groupings and the discursive construction of nationalist hostility, came to the fore. The last decades of the Habsburg Monarchy were shaped by the formation of nationalist movements and the nationalist mobilisation of the masses. 6 Language was no longer simply a means of communication but instead came to be understood as “an emblem of nation-ness.” 7 Nevertheless, Styrians, whose mother tongue was either Slovenian or German, continued to live together in this shared territory and kept communicating with each other daily. They were no hermetically sealed ethnolinguistic groups that were at odds with each other, as national historiographies would later claim.

2Within the same timeframe when Lower Styria was pervaded by questions of nationality, and when faster means of transportation, including the expanding railways, had already increased people’s mobility, postcards became a popular medium of mass communication in the decades leading up to World War I. The world’s first correspondence cards (in German Korrespondenzkarten, in Slovenian listnice and later dopisnice) were introduced in the Habsburg Monarchy as an official means of written communication in 1869. At this time, they were not illustrated, and they quickly grew in popularity because they were less expensive than letters to send by post. The first illustrated examples came into circulation in 1885, when private companies within the Monarchy were authorised to print their own illustrated postcards. In the 1890s, they became a form of mass media, “occupied a significant social communicative space,” and became “the first writing-related technology to be a truly mass vernacular medium.” 8 As of approximately 1897, when the photomechanical reproduction process was adopted as the standard procedure using collotype and halftones, the social use of this particular form of media expanded rapidly and large numbers of postcards came into circulation. By 1912, some 272.7 million postcards had been sent in Austria. 9 Because they were related to the emergence of a travelling public, they played a central role in tourism discourse by directing the tourists’ attention through displays of what was worth seeing and by staging and presenting a region, city, or territory. 10 However, the impact of postcards during this period that predated the telephone went far beyond the tourism industry. Due to a well-established postal service, they were also the fastest means of communicating messages about day-to-day business and events. Their widespread use by a large number of people meant that writing practices used in postcard messages are also of significant historical interest. Since they were a form of informal, everyday writing, postcards were embedded in sets of social practices by which identities were negotiated and social relationships, however far or distant, were stabilised. 11 Postcards were a “young” and somewhat unconventional medium, unencumbered by the rather stiff conventions that applied to letter writing. This also motivated people from all social classes – even those who seldom wrote letters – to start using them.

3. On the Methodology of Working with Postcards

1In general, when working primarily with postcards, one can choose either a quantitative or a qualitative approach. A qualitative approach, which examines single items in depth, is preferable when trying to get a sense of the ordinary people’s identifications and feelings of belonging,12 the everyday life of common people,13 actual (written) language use in everyday life,14 and the general atmosphere during specific time frames, e.g. during World War I.15 Furthermore, the focus can be on the visual information16 or the textual information,17 though preferably both layers of information (textual and visual) should always be considered because in this medium they are inextricably linked. When taking a qualitative approach, it is preferable to connect postcards as a medium “from below” with other sources “from above” (e.g. macro data such as census statistics or official sources). In these instances, microhistory 18 can be reconstructed with a few meaningful postcards, or they can be used to create a more vivid picture of a particular period or set of circumstances than would be possible through isolated numbers or statistics. In this paper, however, a quantitative approach will be used.

2The advantage of a broader view, facilitated by large quantities of postcards, is that the researcher can have a better sense of whether or not a particular specimen is typical or common. Looking at the frequency within a large sample results in a more accurate picture than narrowly focusing on a particular type of postcard or a specific theme. Moreover, when working with larger quantities of postcards, the relationships between the uses of the different languages in a bilingual region such as Lower Styria become more discernable. These relationships, however, need to be interpreted with considerable caution. Every postcard is the product of different interests, which could be financial, pragmatic, or ethnically motivated. Therefore, it is essential to bear in mind that the language printed on postcards does not necessarily reflect the population ratios of a particular area or period, and a single modern collection of postcards does not allow researchers to draw direct conclusions regarding the ethnic distribution patterns. Nevertheless, more extensive collections of postcards from a specific region could portray a linguistic landscape of the power relations at the time they were produced and/or circulated.

3One of the methodological challenges of working with postcards is the need to manage them in large quantities. With the exception of privately produced specimens (mostly photographic postcards), postcards are not one-offs—they are printed and brought onto the market in series. Due to these large quantities, it is not possible to examine every single circulated postcard from a region, so researchers can only try to ensure as broad an overview as possible by examining collections assembled by various institutions and private collectors. Consulting a variety of collections is important because the contents of collections are always dictated by the interests or focus (date of origin, geographical location, etc.) of the institutions and individuals assembling them. For instance, a regional library is usually primarily interested in postcards of the city it is located in and its immediate surroundings, while a supralocal or national collection will generally endeavour to represent an entire region or area of a particular ethnic group. More recent rationales behind the sorting and collecting by public institutions have been guided by nationalist categories of thought as well as by the subsequently-drawn state and administrative boundaries. For example, we found that the postcard collection at the Slovenian National and University Library tends to reflect a more “Slovenian” Lower Styria than the postcard collection at the Styrian Provincial Archives in Graz, which reflects a more “German” version. 19 The same is also true of private collectors. The content of these private collections is shaped by both the different goals and interests of individuals and by the varying market conditions. For example, if a collector sources postcards primarily from flea markets in Klagenfurt or Vienna, these will often contain German handwritten text, since many of the postcards at these markets have been sent to these same predominantly German-speaking cities or regions. In contrast, if postcards are acquired from postcard collectors specialising in a Slovenian region, the percentage of postcards written or printed in Slovenian would, naturally, be higher.

4The three-year research project “Postcarding Lower Styria. Nation, Language and Identities on Picture Postcards (1890–1920)”,20 which this paper is based on, was also assembled according to a particular interest. In this case, the main research focus was on how postcards could provide evidence of the intensifying linguistic and ethnic polarisation or whether they would also reflect bilingualism and national indifference. To this end, we examined large quantities of postcards from Lower Styria from ten different collections that had originated from or had been circulated between 1890 and 1920, and which we recorded and presented in a tabular form. A small selection of them (over 2,200 items) was digitalised, dated, described, categorised, and incorporated into POLOS, our digital repository, where they are now available to the general public. 21 Postcards were scanned and incorporated into the repository if they exhibited content or language relevant to our research questions – that is, if they documented bilingualism, ethnic indifference, hybrid language use, ethnic tensions, and/or a symbolic occupation of a territory, etc. Postcards were also selected for the collection to represent the selected timeframe as well as the geographical area. This means that as many postcards as possible were gathered from small villages throughout Lower Styria, whereas in case of the bigger towns of Maribor/Marburg, Celje/Cilli, and Ptuj/Pettau, we relied on a limited amount of samples. This led to a slightly more “Slovenian” representation of Lower Styria than larger quantities of postcards from the larger towns would have resulted in, since they were most often produced with German captions and in much larger numbers. 22 Overall, POLOS provides a quantitative overview of postcards produced and circulated in Lower Styria between 1890 and 1920 and can claim some intersubjectivity, since it incorporates postcards from nine different public and private collections from Slovenia and Austria. The observations of the linguistic landscape in Lower Styria discussed here are all based on these different institutional and private postcards collections and the selection available in the POLOS repository.

4. Linguistic Landscapes and Language(s) on Postcards

1The concept of linguistic landscapes encompasses multilingual societies by referring “to the visibility and salience of language […] in a given territory.”23 It suggests that the visual representation of languages serves essential informational and symbolic functions by “marking the boundaries of linguistic territories” and transmitting vital information about the “relative power and status of competing language groups.” 24 Therefore, the concept of linguistic landscapes offers a new approach to multilingualism. Even though most research that applies this concept focuses on present-day bilingual regions or cities, 25 I believe it can also be easily applied to historical regions, provided that the necessary material is available. In the case of postcards from the 1890–1920 period, such material is available in large quantities.

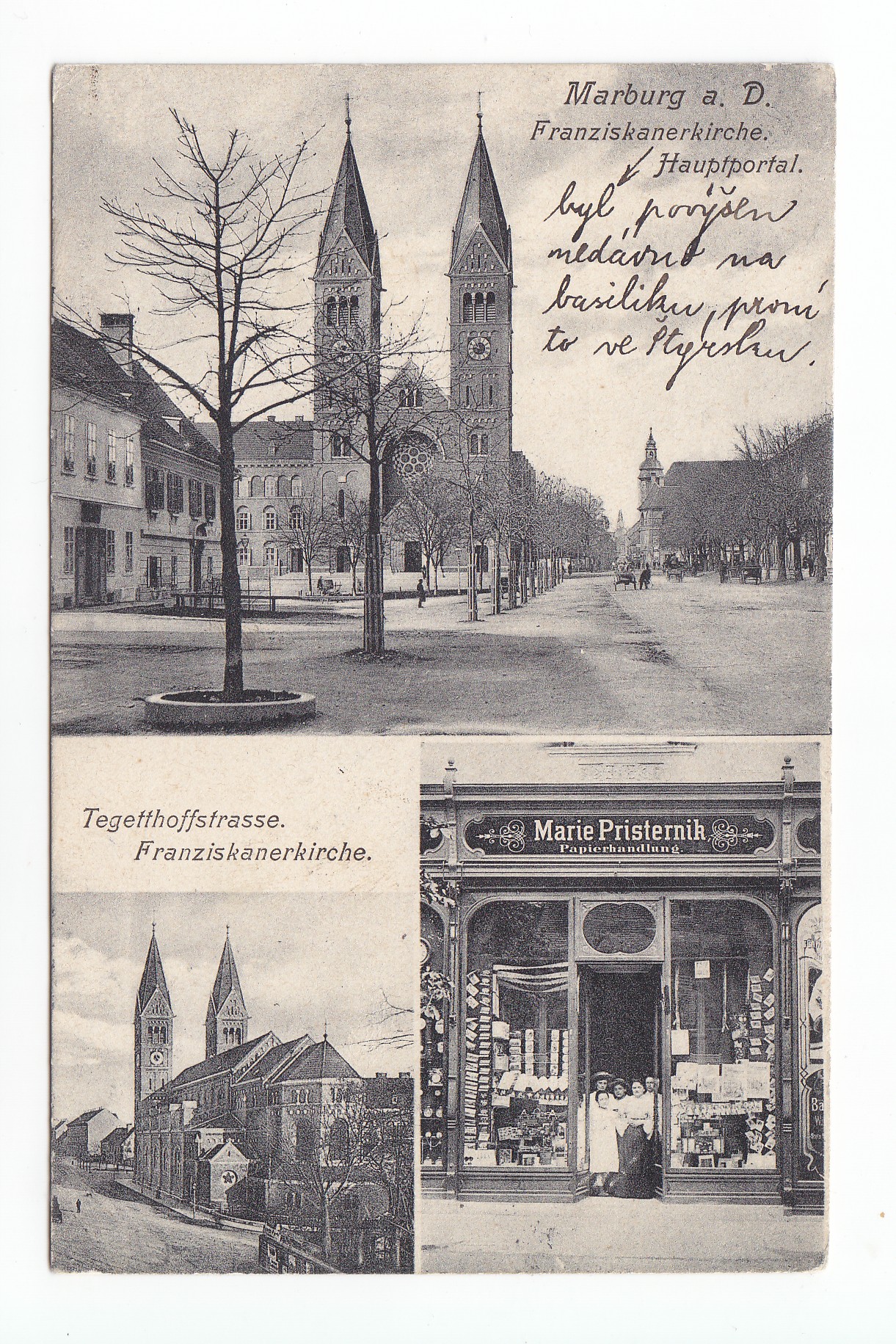

2When looking at the salience of language in a given territory or city, researchers usually distinguish between private, i.e. bottom-up, and government, i.e. top-down, signs. Whereas private signs include, for example, commercial signs on storefronts and businesses and advertising on billboards (in modern-day research also graffiti), government signs refer to public signs such as road signs, place names, street names, and inscriptions on government buildings and public institutions. 26 I would argue that postcards can also be conceived of as a part of public space and can be considered along with other private signs. Firstly, unlike letters, they can be read by anyone handling them, including a landlord or a mail carrier, and are therefore semi-private. People, including those in Lower Styria, were aware of this when writing postcards and were thus more secretive, while private topics were elaborated on in letters, as demonstrated by a common phrase used on postcards from that time: Brief folgt or Pismo sledi (A letter will follow). Secondly, postcards were present in the public sphere as well, since they were sold almost everywhere: in stationery shops, railway stations, restaurants and inns, nearby tourist sites, pubs, and at private clubs. They were displayed in shop windows or on racks in front of stores, which also represented a display of language in the public sphere (see fig. 1). 27 Thirdly, postcards depict the public sphere with portrayals of important buildings, sites, streets, and places, which further perpetuates an image of the public sphere.

1Source: Private collection Pfandl, polos_2085.

3The visibility of languages on postcards can be analysed on different levels. The printed captions accompanying the images are most obvious, which raises the issue of which language was used to frame the image. The decision of which language to use in these captions was, at least until 1918, made by postcard producers and publishers. German-only, Slovenian-only, and bilingual captions existed (usually starting with German followed by a Slovenian translation). German captions were more common on postcards with images of larger towns, whereas Slovenian and bilingual captions were more frequent on postcards depicting small rural villages. 28 It is interesting to note, however, that this is a contrast in linguistic framing only. At the visual level, a common visual culture on postcards from Lower Styria emerged when we were able to establish that the mostly topographic postcards were widely identical in their expressions and visual codes but differed only in the language of their captions. Examples of visually identical postcards with captions in different languages by the same producers seem to indicate that their choice of language was probably motivated more by demand and profit from the potential sales rather than a desire to support nationalist causes. 29

4Secondly, the staging of language in the public sphere on postcards can be detected in the mostly photographic representations of public space. The pictures on postcards offer insights about written signs within the public space when looking at which languages were present in the public sphere through street names, commercial shop signs, advertising billboards, or other written signs. Some of them are government signs (such as inscriptions on public buildings like schools, train stations, etc.), but more frequently they are private signs (such as inscriptions on stores, taverns, restaurants, and advertisements). Evidence collected from examining larger quantities of postcards suggests that in the larger towns, along railway routes, and in tourist resorts, German dominated the public sphere, whereas Slovenian and bilingual signs were much more widely used in the countryside.

5Thirdly, language is, of course, visible in the handwritten messages added by senders. Written language use on postcards can be considered semi-public, as it represented private communication between the sender and the addressee. However, more people could read these messages than just the two primary agents. Even though writing postcards was considered a rather bourgeois activity, members of other social classes also wrote and sent postcards. Hence, traces of a heterogeneous linguistic situation are evident, including a wide range of linguistic proficiency (from highly educated to a very basic command of language), different varieties of language use (particularly with Slovenian texts, which ranged from dialectical and/or vernacular and colloquial language to sophisticated formal language in elegant handwriting), and various forms of language contact. This final category is evident not only from the somewhat rare forms of real code-switching, in which a writer would switch from one language to the other in a single message, but also from the combination of different messages in different languages by different senders (see fig. 7). Moreover, given that Slovenian was, at the time, in the first stages of becoming a fully codified and standardised supraregional “national” language, the influence of other languages (mostly German) is often evident in Slovenian handwritten messages through loan words, loan translations, calques, the acquisition of German syntax and phrases, and so on. This situation also makes postcards a rich source for diachronic linguistics, and in this case for Slovenian Studies. 30

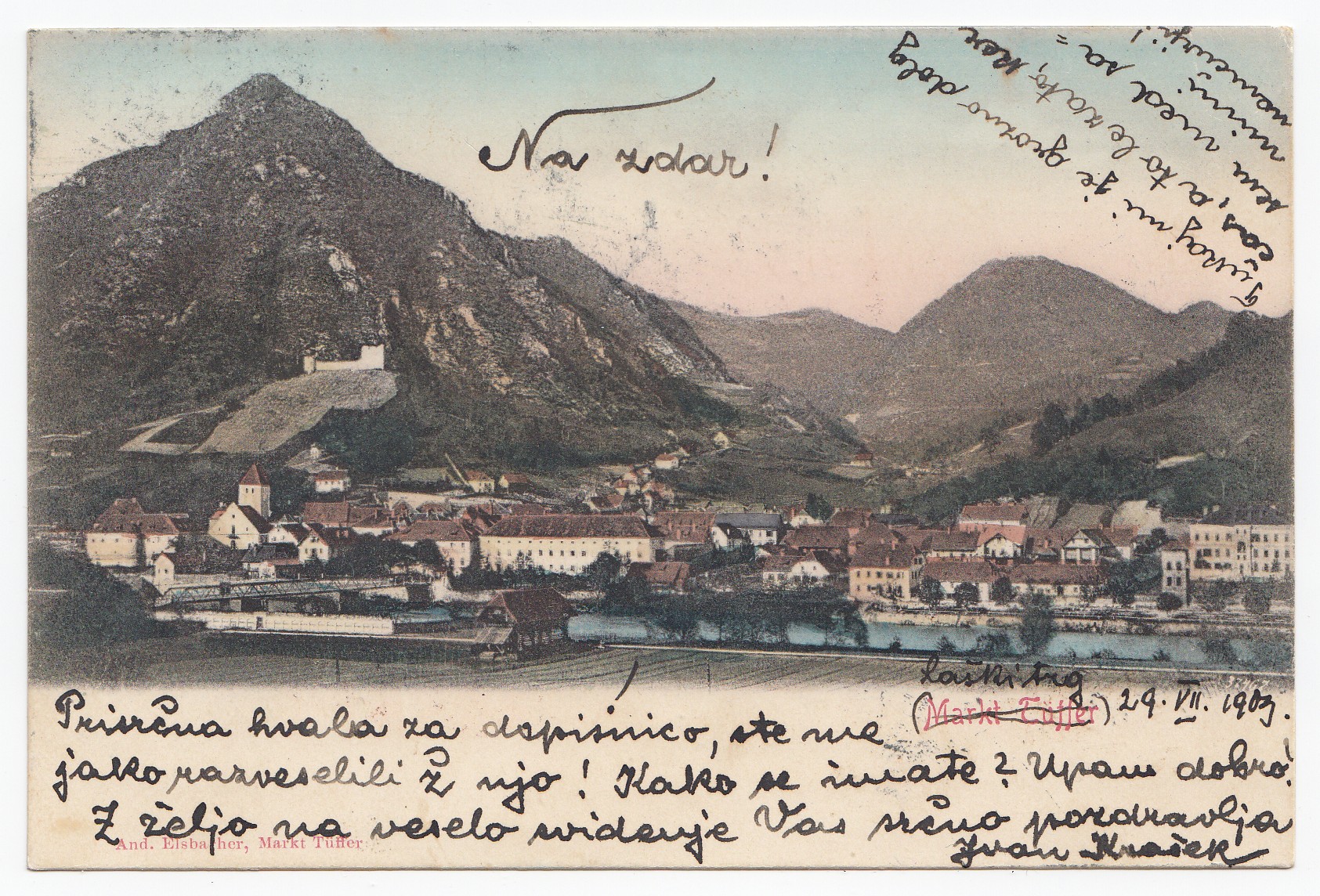

6In terms of social practices, handwritten messages on postcards can offer insights in the way people reacted to the linguistic staging of public space, e.g. erasing expressions in one language or the other, crossing out text printed by publishers, or replacing captions by hand in another language. This phenomenon was rather common at the time (see fig. 2), and examples of this can be found for both languages. Symbolically, these acts deny the language of the other linguistic and national group a place in the semi-public sphere of the postcard as well as in the bilingual region, town, or village. The sender of the postcard in fig. 2 was undoubtedly motivated by nationalist sentiments when crossing out the German toponym and replacing it with the Slovenian equivalent, because he complains in the handwritten message, “ Tukaj mi je grozno dolg čas, a to le zato, ker sem med samimi nemčurji [It’s so boring here, but only because I’m surrounded by all these German wannabes]!” and ends his message with the Slavic salute Na zdar!.

1Source: Osrednja knjižnica Celje, polos_0045.

7Finally, there are the postmarks used by the local post offices, which also contribute to the linguistic staging of public space and are of an official character. As with town signs or writing on public buildings, Slovenian terminology on postmarks became more frequent over time, which indicates a decisively firm claim to the public recognition of the population distribution. Some cities and towns used German postmarks exclusively until 1918, while others – especially small villages in the countryside – used bilingual postmarks. For these, the toponym was in German at the top and then in Slovenian below. If all the previously mentioned traces of language – printed captions, handwritten messages, and most of the signs in the photographic representations of the public sphere – were produced by publishers in the private sector and can be considered private signs, postmarks provide political and administrative legitimacy and are thus government signs.

5. Towns and Rural Villages

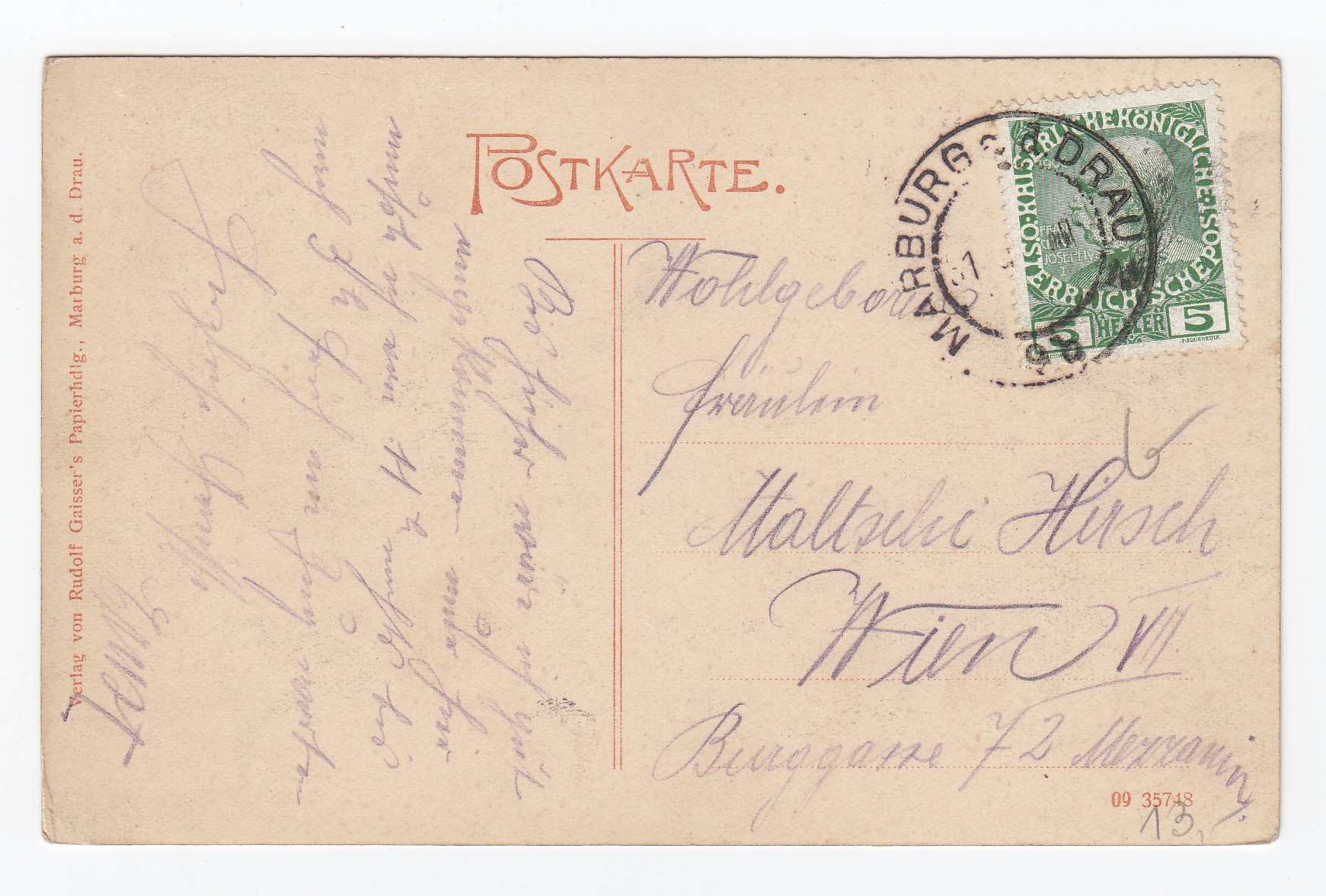

1The different layers of information on postcards and the previously mentioned contrast between the urban and rural areas can be illustrated with examples of rather prototypical postcards. Fig. 3+4, the front and back of a postcard depicting Grajski trg/Burgplatz in Maribor/Marburg, is a typical example from the Lower Styrian towns. The almost hegemonic dominance of German on the postcards was especially present in the city of Maribor/Marburg as well as in the towns of Ptuj/Pettau and Celje/Cilli, which reflected the urban, middle-class ambitions to normatively establish the German character of the representative culture. Maribor/Marburg was also one of the places in Lower Styria that, up until 1918, had a postmark only in German. The printed caption on this postcard is in German, as is the handwritten message. The photograph also contains various signs in the public space, all in German. On the right-hand side is a street sign for I. Stadt. Burg-Gasse, which is a government sign. Below it are advertisements exclusively in German, promoting sewing machines and cultural events. Other parts of this scene contain shop signs on the fronts of the buildings, all of them also exclusively in German. The space depicted here is modern, as is demonstrated by the paved sidewalk and the public streetlights attached to the facades.

1Source: Private collection Lukan, polos_3563.

2This example should not be taken as an indication that there were no Slovenian captions or handwritten texts on postcards from Maribor/Marburg, nor should it be used to indicate that Slovenian was not spoken in Maribor/Marburg. However, postcards from Maribor/Marburg always had an exclusively German postmark, predominantly German captions and handwritten messages, and the photographic representations on postcards depict a public space dominated by signs in the German language. 31 To the visitor’s eye or to the recipient of such a postcard, Maribor/Marburg around 1900 indeed appeared to be a German city, and Slovenian occupied very little space in the public sphere.

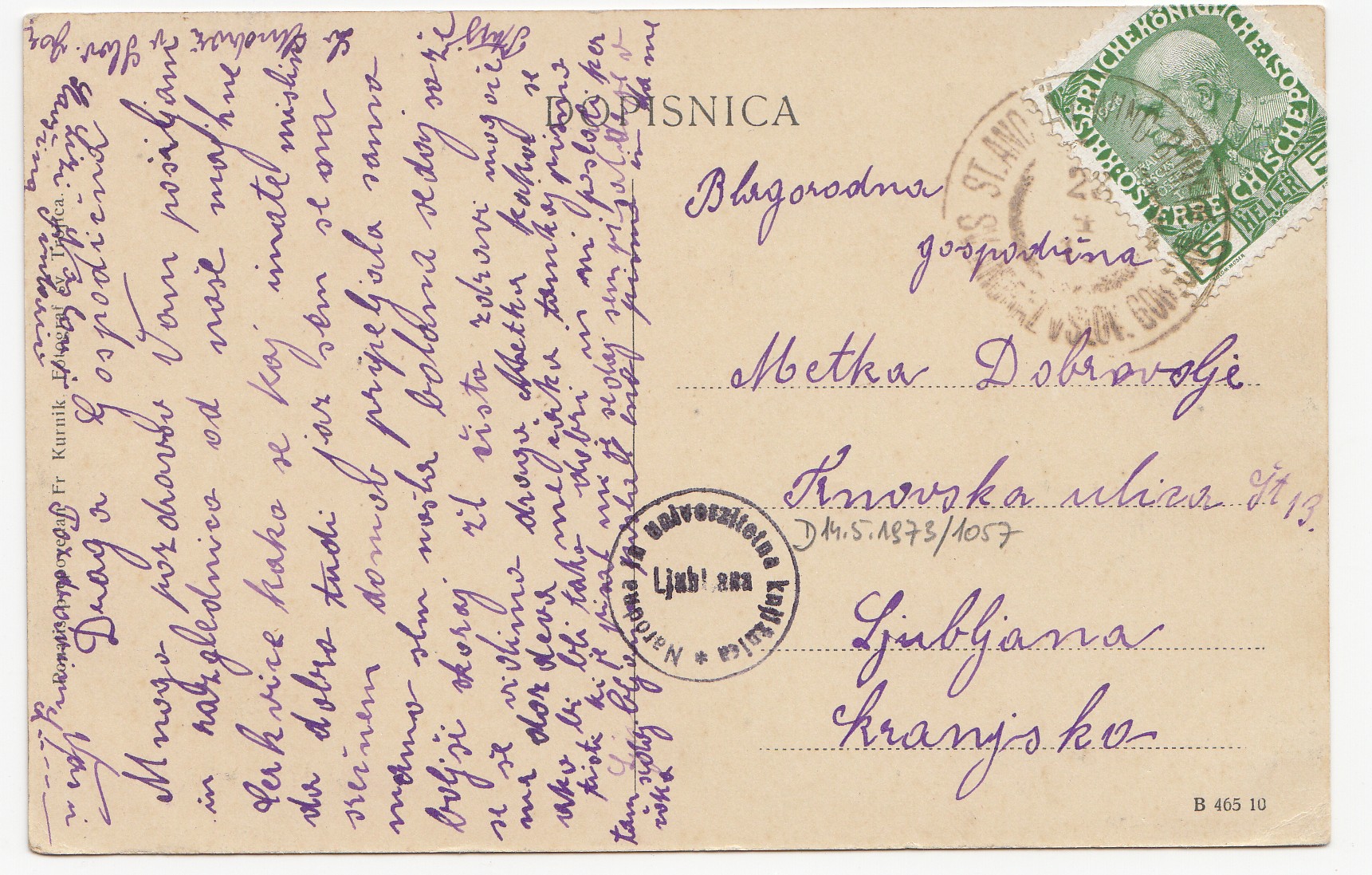

3A different picture of Lower Styria, however, emerges when looking at postcards from the more rural areas like the one in fig. 5+6, which was sent to Ljubljana/Laibach from the Slovenske Gorice/Windische Büheln in the eastern part of Lower Styria. The captions are exclusively Slovenian, the address side uses dopisnica, the Slovenian word for a postcard, and the producer – a local photographer from Sveta Trojica/Heilige Dreifaltigkeit – is mentioned in Slovenian as well. It should be noted that the postmark for this tiny village of Vitomarci (called Sveti Andraž v Slovenskih Goricah until 1952) was bilingual. Typically of such village postcards, the picture side includes a collage of three images depicting what was considered most important in the area. 32 The above image is a wide-angle view of the village church, and below are images of a building containing the local post office/shop on the left and the local elementary school on the right with the locals posing for the camera in front of both buildings. Both buildings bear signs in Slovenian ( Prodajalnica – shop and Narodna šola – national school, meaning elementary school), which shows that the Slovenian language was present in the village’s public sphere. The handwritten message with friendly if rather superficial content is also in Slovenian. 33

1Source: Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, polos_1151.

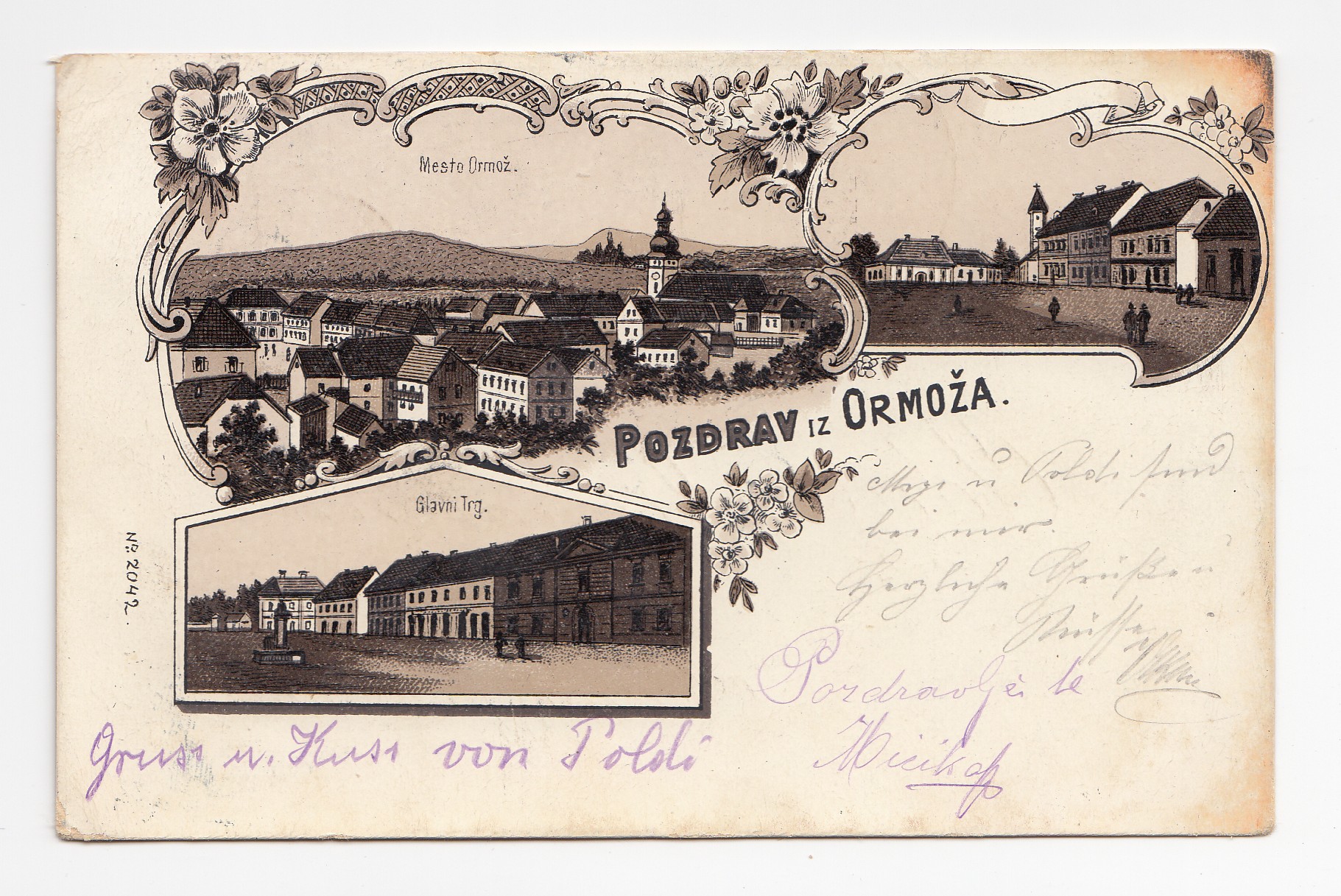

4Naturally, there is a broad range of possible language combinations between these two prototypical examples, including postcards from the countryside with German messages, postcards from the urban areas with Slovenian captions and Slovenian messages etc. Fig. 7 from Ormož/Friedau is an example that falls somewhere in this range.

1Source: Univerzitetna knjižnica Maribor, polos_0617.

5Ormož/Friedau – one of the small towns that, until 1918, had an exclusively German postmark – was framed on postcards with both German and Slovenian captions, and was situated in a predominantly Slovenian-speaking environment. 34 The postcard in fig. 7 contains Slovenian captions and was sent by a group of friends. The messages were written in three different hands: one in Slovenian and two in German. The addressee must have understood both languages, since he was addressed in both. Postcards like these are examples that give a glimpse into the linguistic variety present at the time, and they demonstrate that until 1918, Lower Styria was a truly bilingual area with considerable differences between the urban and rural areas.

6. Official Language Change: 1918–1920

1Postcards can also be used to reconstruct the changes in the political system (as well as the often simultaneous changes in language policy). When the Habsburg Monarchy collapsed in 1918, the balance of power between the language groups shifted dramatically in the public sphere, as did the languages’ visibility. After the new and eventually short-lived State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs (the State of SHS) was established, Slovenian was declared the only official language in November 1918. When the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (the Kingdom of SHS) was formed one month later, in June 1919 this order was followed by a directive that all official and private signs placed in public could only be written in the official language, which was known as Serbo-Croatian-Slovenian. 35 Along with this attempt to Slovenianise the public sphere in regions such as Lower Styria, the German language had to be removed from the semi-public sphere of postcards as well. To continue to sell and use postcards that had already been produced and stocked, postcard vendors would systematically stamp over or cross out German captions, place names, and greetings, and replace them with their Slovenian equivalents. Accordingly, new postage stamps, known as the Verigarji stamps, also came into circulation and are still popular today among philatelists. The former German or bilingual postmarks were not suitable for the new state, but due to the general shortage of supply and material, they could not be removed from circulation as quickly as the new legislators would have liked, while the local postage authorities had to continue using the old Austrian postmarks. The German name on bilingual postmarks was simply scraped off, leaving the postmark half empty in the upper part. Postmarks that were exclusively German were usually left as is, or, in some cases, the German toponym was also scraped off, leaving the postmark completely empty or “mute.” Under the new state, postmarks were gradually replaced by new ones with the toponym in Slovenian above a transliteration in Cyrillic letters (e.g. Maribor – Марибор). 36

![Figure 8 and 9: [stamped over after 1918] producer , produced before 1918, sent in 1919 from Ptuj/Pettau to Silesia.](https://ojs.inz.si/pnz/article/download/601/version/536/1034/3188/figure_8.jpg)

![Figure 8 and 9: [stamped over after 1918] producer , produced before 1918, sent in 1919 from Ptuj/Pettau to Silesia.](https://ojs.inz.si/pnz/article/download/601/version/536/1034/3189/figure_9.jpg)

1Source: Private collection Pfandl, polos_2120.

2Fig 8+9 is an item produced before 1918 but later adapted by a vendor who stamped a Slovenian greeting on it, even though the old German caption ( Pettau) is still legible. The postcard features a Verigar postage stamp handed out by the State of SHS that was still in use from 1919 to 1920 (even though the short-lived state no longer existed). In 1920/21, new postage stamps with King Alexander Karađorđević were issued by the Kingdom of SHS. 37 Interestingly, in July 1919, the old German k.k. postmark was still being used in Ptuj/Pettau. The handwritten message in fig. 8+9 was written in German, illustrating that German had not vanished as a language of private communication after 1918, since a considerable number of Germans stayed, even though many others left Lower Styria after 1918.

3As these examples demonstrate, postcards can also serve as a valuable source of information for illustrating a systematic shift to the new statehood during the years of change between 1918 and 1920. In this competition for linguistic visibility and the associated encoded concepts of identity in the semi-public sphere, a differentiation must again be made between private senders and governmental language use: crossing out and stamping over postcard captions occurred after 1918 was ordered by the state, so these – along with the new postmarks and postage stamps – can be categorised as government signs.

7. Conclusion

1Picture postcards in considerable numbers can help portray the linguistic landscape of a particular region and create a clearer picture of language distribution patterns in the linguistically mixed regions and of power relations between certain linguistically diverse – although not necessarily culturally diverse – groups. As illustrated in this paper using the example of Lower Styria at the beginning of the twentieth century, which was a region inhabited by Slovenian- and German-speaking Styrians, postcards can be a valuable source of information for historically linguistically mixed regions. When looking back in history from a modern perspective and often guided by the national narratives or the borders of the today’s national states, even historians can sometimes tend to underestimate how linguistically mixed large parts of the Habsburg Empire actually were. Research using postcards similar to the project discussed in this paper could also be conducted for other multiethnic and multilinguistic empires or other linguistically mixed regions of the Habsburg Empire such as Southern Tyrol, Galicia, Bukovina, Bohemia, Moravia, the Austrian Littoral, Carinthia, or Carniola. A comparative approach looking at different regions during the same timeframe would be a desideratum. It could illustrate not only the extent to which German remained a supraregional lingua franca in the Austrian half of the empire, but also the extent to which other languages became increasingly salient in the late Habsburg Empire and claimed their part of the public discourse and visibility in the public sphere. Furthermore, as was the case during the years of the system change between 1918 and 1920, postcards can also illustrate the power relations changes in the public sphere as well as new language policies, applied under a new rule. In conclusion, postcards also illustrate how language as the central ethnic marker in the Habsburg Central Europe ceased being simply a pragmatic tool of communication and instead became a symbol of national identity.

Sources and literature

- Almasy, Karin. Wie aus Marburgern "Slowenen" und "Deutsche" wurden: Ein Beispiel zur beginnenden nationalen Differenzierung in Zentraleuropa zwischen 1848 und 1861. Graz: Artikel-VII-Kulturverein für Steiermark – Pavelhaus, 2014.

- Almasy, Karin. “The Linguistic and Visual Portrayal of Identifications in Slovenian and German Picture Postcards (1890–1920).” Austrian History Yearbook, 49 (2018): 41–57.

- Almasy, Karin. “Postkartengeschichte(n). Der Unterschätzte Quellenwert von handschriftlichen Spuren auf Postkarten für Sozial-, Alltags- Und Mikrogeschichte.” In: Bildspuren, Sprachspuren. Postkarten als Quelle zu mehrsprachigen Regionen der Späten Habsburger Monarchie. Edited by Karin Almasy, Heinrich Pfandl and Eva Tropper [upcoming]. Bielefeld: transcript, 2020.

- Pfandl, Heinrich. “Slowenische Identität(en) auf Ansichtskarten der Monarchie zwischen 1890 und 1918. Am Beispiel des österreichischen Kronlandes Steiermark.” In: Konfliktszenarien um 1900: Politisch – Sozial – Kulturell; Österreich-Ungarn und das russische Imperium im Vergleich = Scenarii Konfliktov Na Rubeže XIX - XX Vekov; Političeskie – Socialʹnye – Kulʹturnye; Avstro-Vengerskaja I Rossijskaja Imperii. Edited by Peter Deutschmann, Volker Munz and Ol'ga Pavlenko, 251–88. Wien: Praesens-Verl., 2011.

- Thurlow, Crispin, Adam Jaworski, and Virpi Ylänne-McEwen. “'Half-Hearted Tokens of Transparent Love’: Host and Tourist Perceptions of Postcard Representations.” Tourism, Culture, Communication, 5, No. 1 (2005): 93–104.

- NUK - Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica:

- Kartografska in slikovna zbirka razglednic.

- OKC - Osrednja knjižnica Celje, oddelek za domoznanstvo, zbirka razglednic.

- Private postcard collection Lukan.

- Private postcard collection Pfandl.

- UKM - Univerzitetna knjižnica Maribor:

- Zbirka drobnih tiskov, zbirka razglednic.

1All the postcards cited come from these postcard collections; available as well on the digital repository of postcards from Lower Styria POLOS: http://gams.uni-graz.at/context:polos.

Karin Almasy

JEZIKOVNA KRAJINA SPODNJE ŠTAJERSKE NA RAZGLEDNICAH (1890–1920)

POVZETEK

1Ilustrirana razglednica je v devetdesetih letih 19. stoletja postala prvi množični fenomen komunikacije in je bila v času pred telefonom tudi najpomembnejše in najhitrejše vsakodnevno komunikacijsko sredstvo. Razglednice so se uporabljale ne le v prvem nastajajočem turizmu, temveč tudi za opravljanje vsakodnevne komunikacije. Uporabljali so jih ljudje različnih družbenih slojev in različnih stopenj izobraženosti. Zato je razglednica z začetka 20. stoletja inovativen vir za zgodovinopisje, ker je bila zelo blizu vsakdanjemu življenju in jo je na mnogoterih ravneh oblikovalo sožitje več jezikov v jezikovno mešanih področjih habsburške monarhije. Tako lahko raziskovalcem nudi poseben dostop do struktur dvo- ali večjezičnih pokrajin. Pričujoči članek s pomočjo razglednic nudi vpogled v takšno dvojezično regijo habsburške monarhije: v Spodnjo Štajersko (Untersteiermark/Lower Styria/današnja Štajerska).

2V obdobju, ko so razglednice postale množični fenomen splošne komunikacije, je Spodnjo Štajersko, južno pokrajino kronovine Štajerske, prežemalo vprašanje »narodnosti«. Ločnica med narodnima skupinama je postal jezik. Jezik ni bil več pragmatično sredstvo komunikacije, temveč je postal vir identitete in simbol narodnosti. V drugi polovici 19. stoletja je bila dvojezična pokrajina v razpravah označena za miroljubno, čeprav asimetrično sobivanje obeh jezikov. Nemščina je bila v zavidljivejšem položaju. Kodificirana je bila prej kot slovenščina, bila je dominanten jezik urbanega okolja in je veljala za jezik višjega sloja ter višje izobrazbe. Glede na to je bila v večini primerov družbenega napredka povezana s prilagajanjem, dobro obvladanje nemščine pa je bilo ekonomsko relevantno predvsem za slovenske družine. Tako je bila dvojezičnost zelo razširjena, še posebej med Slovenci. Nemški jezik prevladuje na razglednicah večjih mest in trgov Spodnje Štajerske, medtem ko so bile slovenske in dvojezične razglednice bolj razširjene na podeželju.

3Članek se naslanja na koncept »jezikovnih zemljevidov« (linguistic landscapes). Ta koncept k večjezičnim družbam pristopa z opiranjem na »vidnost in prepoznavnost jezika […] na danem področju«. Pri tem izhaja iz domneve, da vizualna reprezentacija jezikov služi pomembnim informativnim in simbolnim funkcijam, »označuje meje jezikovnega področja« in posreduje pomembne informacije o »sorazmerni moči in statusu tekmujočih jezikovnih skupin« (Landry/Bourghis 1997: 24). Zato koncept »jezikovnih zemljevidov« ponuja nov pristop k večjezičnosti. Medtem ko se raziskovalci v prvi vrsti osredinjajo na opaznost različnih jezikov na javnih in komercialnih oznakah v današnjem javnem prostoru, želi ta članek pokazati, da so lahko razglednice z začetka 20. stoletja prav tako razumljene kot del tega – zgodovinskega – javnega prostora. S primeri razglednic Spodnje Štajerske in z vpogledi v rezultate triletnega raziskovalnega projekta »Postcarding Lower Styria. Nation, Language and Identities on Picture Postcards (1890–1920)« članek nudi pregled o »jezikovnem zemljevidu« Spodnje Štajerske in želi pokazati dvojezično sobivanje slovenščine in nemščine v skupnem prostoru Spodnje Štajerske med 1890 in 1920.

* Mag. Dr. phil. MA, University of Graz, Institut für Translationswissenschaft, Merangasse 70/1, 8010 Graz, Austria; >karin.almasy@uni-graz.at

1. W. J. Thomas Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago, Ill.: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1995).

2. We stress this claim in our upcoming publication: Karin Almasy, Heinrich Pfandl and Eva Tropper, eds., Bildspuren, Sprachspuren. Postkarten als Quelle zur Mehrsprachigkeit in der späten Habsburger Monarchie (Bielefeld: transcript, 2020).

3. Rodrique Landry and Richard Bourghis, “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality. An Empirical Study,” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16, 23–49 (1997): 23.

4. See e.g. in memoirs of the anational times, such as: Anton Šantel, Zgodbe moje pokrajine: [z lastnimi risbami], ed. Janez Kajzer (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 2006). And further: Karin Almasy, Wie aus Marburgern “Slowenen” und “Deutsche” wurden: Ein Beispiel zur beginnenden nationalen Differenzierung in Zentraleuropa zwischen 1848 und 1861 (Graz: Artikel-VII-Kulturverein für Steiermark - Pavelhaus, 2014).

5. Joshua Fishman, “Bilingualism with and Without Diglossia; Diglossia with and Without Bilingualism,” Journal of Social Issues, XXXIII, No. 2 (1967).

6. For Lower Styria, see: Janez Cvirn, Trdnjavski trikotnik: politična orientacija Nemcev na Spodnjem Štajerskem (1861–1914) (Maribor: Obzorja, 1997). Janez Cvirn, Aufbiks!: Nacionalne razmere v Celju na prelomu 19. v 20. stoletje (Celje: Visual Production, 2006). Pieter M. Judson, Guardians of the Nation: Activists on the Language Frontiers of Imperial Austria (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2006).

7. Benedict R. O’G Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Rev. ed. (London, New York: Verso, 2006), 133.

8. Nigel Hall and Julia Gillen, “Purchasing Pre-Packed Words: Complaint and Reproach in Early British Postcards,” in: Ordinary Writings, Personal Narratives: Writing Practices in 19th and Early 20th Century Europe, ed. Martyn Lyons (Bern: Lang, 2007), 102, 103.

9. For this number, Békési is citing the statistics of the Austrian postage service and it refers to the territory of today’s Republic of Austria. See: Sándor Békéski, “Die topografische Ansichtskarte. Zur Geschichte und Theorie eines Massenmediums,” Relation. Beiträge zur vergleichenden Kommunikationsforschung. Online Edition 1 (2004): 385.

10. David Barton and Nigel Hall, eds., Letter Writing as a Social Practice. Studies in Written Language and Literacy V. 9 (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2000), 107. Crispin Thurlow, Adam Jaworski and Virpi Ylänne-McEwen, “‘Half-Hearted Tokens of Transparent Love’: Host and Tourist Perceptions of Postcard Representations,” Tourism, Culture, Communication, 5, No. 1 (2005). Adam Jaworski, “Linguistic Landscapes on Postcards: Tourist Mediation and the Sociolinguistic Communities of Contact,” Sociolinguistic studies 4, No. 3 (2010).

11. See further: Barton and Hall, Letter Writing, 7. See also: Esther Milne, Letters, Postcards, Email: Technologies of Presence (New York, London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2013). Anett Holzheid, Das Medium Postkarte: Eine Sprachwissenschaftliche und mediengeschichtliche Studie (Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag, 2011).

12. Karin Almasy, “The Linguistic and Visual Portrayal of Identifications in Slovenian and German Picture Postcards (1890–1920),” Austrian History Yearbook 49 (2018). Heinrich Pfandl, “Slowenische Identität(En) auf Ansichtskarten der Monarchie zwischen 1890 und 1918. Am Beispiel des Österreichischen Kronlandes Steiermark,” in: Konfliktszenarien um 1900: Politisch - Sozial - Kulturell; Österreich-Ungarn und das russische Imperium im Vergleich = Scenarii Konfliktov Na Rubeže XIX - XX Vekov; Političeskie - Socialʹnye - Kulʹturnye; Avstro-Vengerskaja I Rossijskaja Imperii, ed. Peter Deutschmann, Volker Munz and Ol’ga Pavlenko (Wien: Praesens-Verl., 2011).

13. Martin Sauerbrey, “"Danes na peči faulencam. Jutri grem pa na ‘Jegerbal’" – Was man aus Postkarten aus der Untersteiermark aus den Jahren 1880–1920 lernen kann,” VII. Jahresschrift des Pavelhauses, 2017.

14. Heinrich Pfandl, “Razglednice Spodnje Štajerske kot vir informacij o obdobju med letoma 1890 in 1918,” in: Rokopisi slovenskega slovstva od srednjega veka do moderne, eds. Aleksander Bjelčevič, Matija Ogrin and Urška Perenič (Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete, 2017). Heinrich Pfandl, “'Wie ist es bei den Slowenen Lustig'. Slowenisches auf topographischen Ansichtskarten des Kronlandes Steiermark 1890–1918,” Signal. Jahresschrift des Pavelhauses (2010/2011).

15. Karin Almasy and Martin Sauerbrey, “"Noviga ni nič. Vojska je hudič." Prva svetovna vojna na razglednicah s Spodnje Štajerske,” Zgodovina za vse 26, (2019): 46–61.

16. Karin Almasy, “Prosperität und Modernisierung der Untersteiermark zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts im Spiegel illustrierter Postkarten,” in: Prosperität und Wirtschaftsaufschwung im Donau-Karpaten-Raum (Arbeitstitel), ed. Harald Heppner (2019).

17. Karin Almasy, “Postkartengeschichte(n). Der Unterschätzte Quellenwert von handschriftlichen Spuren auf Postkarten für Sozial-, Alltags- und Mikrogeschichte,” in: Bildspuren, Sprachspuren. Postkarten als Quelle zu mehrsprachigen Regionen Der späten Habsburger Monarchie, eds. Karin Almasy, Heinrich Pfandl and Eva Tropper (Bielefeld: transcript, 2020).

18. For a good overview and the methodology of microhistory, see: Sigurður G. Magnússon and István Szíjártó, What Is Microhistory? Theory and Practice (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2013).

19. For an overview of our quantitative findings, see Postcarding Lower Styria, http://gams.uni-graz.at/archive/objects/context:polos/methods/sdef:Context/get?mode=statistics (18 October 2019).

20. Funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (project number 28950-G28) and carried out between 2016 and 2019 at the Department of Slavic Studies at the University of Graz under the direction of Heinrich Pfandl. The author of this paper was a research assistant within this project. The result is the digital repository of postcards from Lower Styria called POLOS, an exhibition, and two travelling exhibitions as well as a monographic publication framing the exhibition, all called Štajer-mark. For more information about our work, see Postcarding Lower Styria https://postcarding.uni-graz.at/en/projekt/ (18 October 2019) and: Karin Almasy and Eva Tropper, Štajer-Mark: 1890-1920: Der gemeinsamen Geschichte auf der Spur: Postkarten der historischen Untersteiermark = Po sledeh skupne preteklosti: Razglednice zgodovinske Spodnje Štajerske (Laafeld: Artikel-VII-Kulturverein für Steiermark – Pavelhaus; = Kulturno društvo Člen 7 za avstrijsko Štajersko - Pavlova hiša, 2018).

21. Available at Postcarding Lower Styria, http://gams.uni-graz.at/context:polos (18 October 2019). Our thanks to the institutions and private collectors who granted us access to their collections – without their cooperation, our research would not have been possible. Thanks also to the Centre for Digital Humanities ZIM of the University of Graz, which has developed the repository with us. Our partners were the following: the regional libraries Osrednja knjižnica Celje, Univerzitetna knjižnica Maribor, Knjižnica Ivana Potrča Ptuj, the Admont monastery, the Slovenian National and University Library (NUK) and the Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia (MNZS) in Ljubljana, the Styrian Regional Archive Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv, as well as the private collectors Walter Lukan, Teodor Domej, and Heinrich Pfandl. All institutions and collectors with the exception of the Styrian Regional Archive allowed us to scan a selection of the most relevant postcards and put them in our digital repository. Therefore, we carried out our research within ten different postcard collections, but scans from only nine are available on POLOS. The inventory polos-numbers in the citations of specific postcards cited later on refer to their identification within the digital repository.

22. In the POLOS repository, 55 % of postcards include printed German captions, while 28 % are Slovenian and 17 % are bilingual. However, only 48 % of handwritten messages are in German, while 41 % are Slovenian and the remaining 4 % contain some sort of language contact (e.g. different people writing in different languages, a message from a single writer exhibiting bilingual or diglottic use, code switching, or other hybrid lexical forms). See as a pie chart: Postcarding Lower Styria, http://gams.uni-graz.at/archive/objects/context:polos/methods/sdef:Context/get?mode=statistics (18 October 2019).

23. Landry and Bourghis, “Linguistic Landscape,” 23.

24. Ibid., 24.

25. For examples, see the case studies (of modern-day Israel, Bangkok, Tokyo, Friesland and the Basque country) discussed in: Durk Gorter, ed., Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 2006), http://site.ebrary.com/lib/alltitles/docDetail.action?docID=10132110.

26. Landry and Bourghis, “Linguistic Landscape,” 26. Gorter, Linguistic Landscape, 3

27. Due to limited space, I will refrain from always including both sides of a postcard, even though this would be preferable. In cases like these here, in which I discuss a certain phenomenon on just one side, only this side is depicted.

28. POLOS, which contains 2,243 postcards, provides evidence for this claim, since it is possible to search for various villages and towns. Within the Collection, you can search for specific villages and towns by both their Slovenian and their historical German names.

29. Almasy and Tropper, Štajer-mark, 38–41.

30. See further for Slovenian: Pfandl, “Razglednice Spodnje Štajerske,” in: Rokopisi slovenskega slovstva od srednjega veka do moderne. For Bulgarian, see: Sebastian Kempgen, “Postkarten als Quelle zur bulgarischen Sprachgeschichte der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts,” Slavistische Linguistik 2006/2007 (2009).

31. POLOS contains 282 specimens from Maribor/Marburg, of which only 29 (10 %) had a Slovenian caption, 17 had a bilingual one, and 8 had no inscription. The rest – 228 out of 282 (81 %) of these postcards from Maribor/Marburg – had a German caption. The results for the handwritten messages is quite similar, even though the Slovenian-speaking population becomes slightly more visible here: of the 241 postcards from Maribor/Marburg that contain a handwritten message (41 empty ones were not considered), 52 (22 %) have a Slovenian message, 8 have some kind of language contact (bilingualism, code-switching, etc.), 24 were written in other languages (Czech, Italian, Croatian, etc.), while the majority (157 or 65 %) contained messages handwritten in German.

32. Almasy and Tropper, Štajer-mark, 54–57.

33. The sample for Vitomarci is much smaller than the one for Maribor/Marburg in our database, and it paints a definite picture: both the captions and the handwritten messages of these five items were in Slovenian only. If for argument’s sake the sample were to be extended to other neighboring villages in the area of Slovenske Gorice – like Cerkvenjak (formerly Sv. Anton), Sv. Trojica, Juršinci (formerly Sv. Lovrenc), Benedikt (formerly Sv. Benedikt), Trnovska Vas (formerly Sv. Bolfenk) and Mala Nedelja – the sample would include 41 postcards from these 7 small villages. Of these 41 postcards, 39 had a printed caption (two were empty), of which only 5 had a German caption, 7 a bilingual caption, while the majority of 27 cards (66 %) had a Slovenian caption. The language of the handwritten messages on the postcards from these villages paints a similar picture: of these 41, 2 were empty, 2 were written in other languages, 8 were in German, and the majority of 29 postcards (71 %) had a Slovenian handwritten message.

34. Ormož/Friedau is a good example of a truly mixed language situation: of the 21 postcards of Ormož/Friedau in our sample, 13 had a German caption and 8 a Slovenian one. Of these 21 postcards, 19 contained a handwritten message: 3 included language contact, 7 were written in Slovenian, and 8 in German, so the distribution of languages was somewhat more even.

35. Reinhard Reimann, “‘Für echte deutsche Gibt es bei uns genügend Rechte’. Die Slowenen und Ihre deutsche Minderheit 1918-1941,” in: Slowenen und Deutsche im gemeinsamen Raum: Neue Forschungen zu einem komplexen Thema, ed. Harald Heppner (München: R. Oldenburg, 2002), 134.

36. For visual examples of all the signs of system change on postcards, see: Almasy and Tropper, Štajer-mark, 162–69.

37. Bezljaj Krevel, “Slovenska pošta, telegraf,” in: Pošta na slovenskih tleh, ed. Andrej Hozjan (Maribor: Delo, 1997), 190.