Cultural and Historical Overview of the Life of the Painter Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929), I. The Painter’s Beginnings and Settling in Ljubljana*

IZVLEČEK

KULTURNOZGODOVINSKI ORIS ŽIVLJENJA SLIKARJA HEINRICHA WETTACHA (1858–1929), I.; ZAČETKI IN USTALITEV SLIKARJA V LJUBLJANI

1Članek prinaša študijo o življenju, delovanju in širši družbeni vpetosti slikarja Heinricha Wettacha (1858–1929), ki je deloval v Ljubljani od leta 1885 do konca prve svetovne vojne, ter ga s tem konkretneje usidra tudi v kulturni milje kranjske prestolnice na prelomu stoletja. Ne glede na to, da je s svojim slikarskim in hkrati tudi aktivnim glasbenim delovanjem v skoraj štirih desetletjih pustil močan pečat na kranjski kulturi in družbi ter da je bil v svojem času vsekakor tudi eden najbolj prepoznavnih ljubljanskih kulturnikov, je namreč danes skoraj neznan. V članku poskušam tudi osvetliti, zakaj je tako.

2Ključne besede: Heinrich Wettach, Ljubljana okoli 1900, nemško čuteči kranjski kulturni krog, slovensko slikarstvo 19. stoletja, avstrijsko slikarstvo 19. stoletja, nacionalni slog v arhitekturi

ABSTRACT

1The primary goal of this article is to provide a brief study of the life, work and extensive social commitments of the painter Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929) who lived and worked in Ljubljana from 1885 until the end of World War I, as well as to position him firmly within the cultural context of the Carniolan capital at the turn of the century. Wettach left a significant mark on Carniolan culture and society and was one of the most recognisable cultural figures of his time in Ljubljana, yet he remains virtually unknown today. The article seeks to shed light on the reasons for this.

2Keywords: Heinrich Wettach, Ljubljana around 1900, German-leaning cultural circle of Carniola, Slovenian 19th-century painting, Austrian 19th-century painting, national style in architecture

1.

1The main goal of the two articles that will be published in two consecutive issues of Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino/Contributions to Contemporary History is to provide a foundational study about the life, work and extensive social commitments of the painter Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929) who lived and worked in Ljubljana from 1885 until the end of World War I and thus place him firmly within the cultural milieu of the Carniolan capital at the turn of the century.

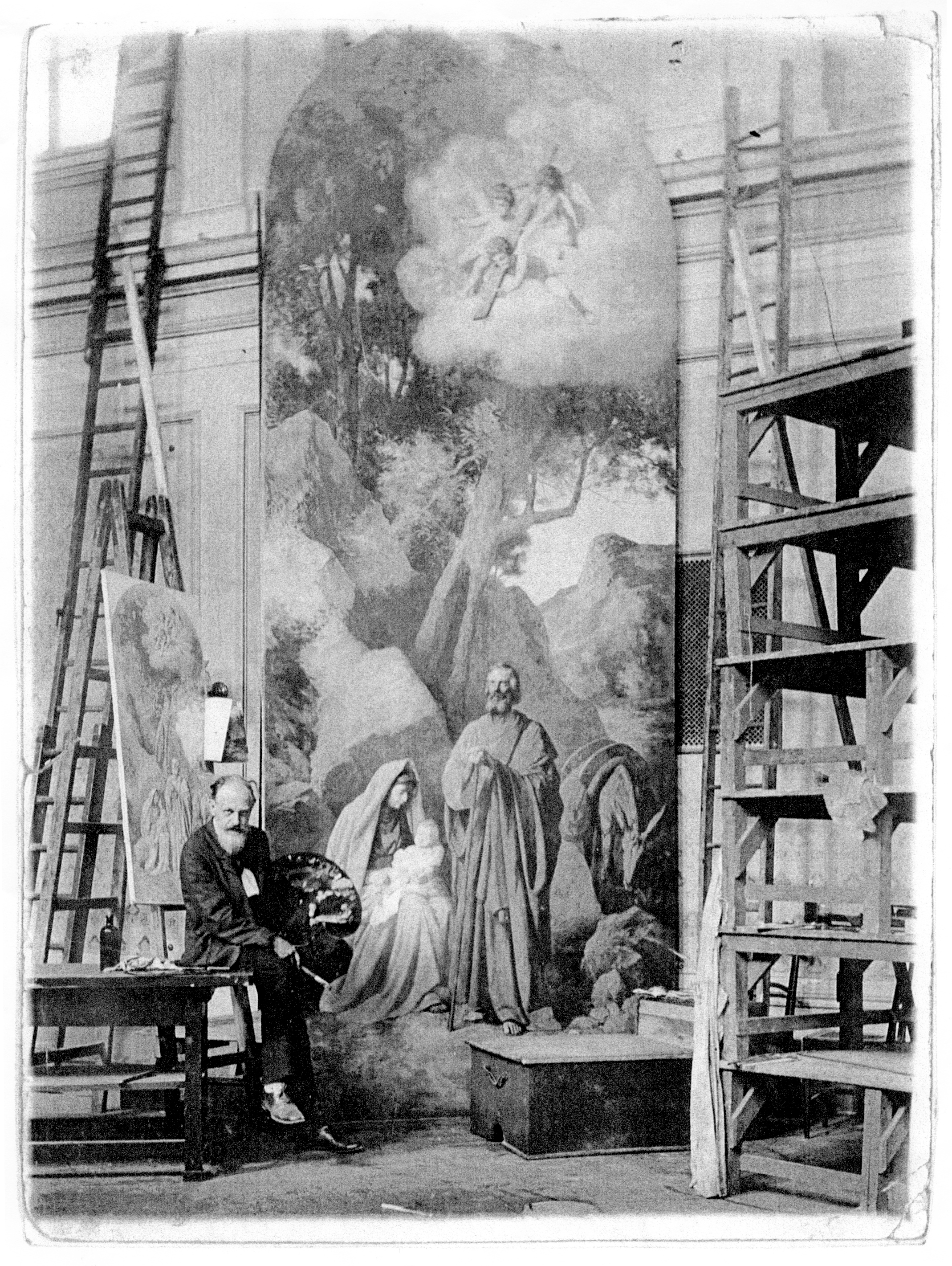

Source: City Museum of Ljubljana (MGML)

2His almost four decades of painting and musical activities left a strong mark on the Carniolan culture and society and made him one of the most recognisable cultural figures in Ljubljana, yet today Wettach remains practically unknown. The articles will shed light on the main reasons for his being ignored in Slovenian art history: his political stance and his belonging to the German-leaning Carniolan cultural circle.

3Although a large majority of Carniolans saw their present and future within Austria in one way or another, throughout the final decades of the 19th century and well into World War I, polarisation along national lines was strongly under way, with many finding themselves at its extreme poles: either more intensely connected to the (Yugo)Slav, or with the wider German, not only cultural but also political space.1 Based on my research this far, it appears that Wettach belonged to the latter, and within the broad spectrum of the Carniolan German-leaning population, he would most fairly be classified with the so-called German nationalists.2 We cannot determine if and which of the more radical ideas of this movement he embraced, and if we detect them, we cannot say exactly when, why, or to what extent he embraced them. For example, did his entire family convert to Protestantism in 1901 for pragmatic reasons, so he could align himself with his professional circle, his clients and buyers, or was the move earnest and true to Wettach’s actual personal political beliefs? Was it perhaps both? Or did – and we have our doubts – Wettach’s dormant religious belief suddenly awaken, and could, in time, even steer him into Ariosophy or perhaps some other form of neo-paganism towards which a part of the pan-Germanic movement was veering?3 When it comes to worldviews that German-leaning and Slovenian-leaning Carniolans shared, for example strong antisemitism, we also cannot explain whether and how Wettach’s antisemitism differed from the antisemitism of Slovenian-leaning Carniolans.4 Therefore, we should keep in mind that, because of the specific way Slovenians see – and are taught about – the past, the artist is viewed in a negative light, even seen as an extremist, although his actions or expressions were no different to those of the Slovenian nationalists; for example, the long-term mayor of Ljubljana Ivan Hribar or, in visual arts the Vesna Society, a Slovenian-Croatian student art association.5 To have a better and contextualised understanding of Wettach’s Germanness, this two-part presentation will place more emphasis on certain factors: this article introduces the specific design of the Wettach family’s three houses that the spouses had built at the time, while the upcoming one looks at the painter’s and his wife’s extensive social commitments. We should also keep in mind that the (much larger) Slovenian-leaning population had their own aesthetics and social activities.

4Taking everything into consideration, it is understandable that the yield of data on Heinrich Wettach’s life and work is scant. Methodologically speaking, the key to the articles are semi-structured interviews with the painter’s grandson Harald Wettach (the son of the painter’s son Reinhard), whom I interviewed over a decade ago in Vienna. The grandson gave me a number of family heirloom photos to use, and some appear in the article, but above all, he contributed important insights and biographical data about the painter’s life, which I have combined with information from other sources, particularly periodicals of the time. The most important among them were, of course, Carniolan German-language newspapers, particularly the main newspaper, Laibacher Zeitung, but also some others for example, Cillier Zeitung from Celje and Villacher Zeitung from Villach. The painter was rarely mentioned in the Slovenian-language Carniolan press, which tended to ignore the activities of the German-speaking Carniolan cultural circles, whenever possible.6

5Contemporary Slovenian art history more or less follows this attitude, as Wettach only occasionally appears in exhibition catalogues of Ljubljana museums and galleries, which possess many of his works.7 This unusual disharmony between an abundant preserved body of work – even displayed in some museum’s permanent exhibitions – and a scant art history research of this, indeed a noticeably conservative painter is tellingly complemented by the fact that the first specific art history study on Wettach, published in Varstvo spomenikov by Breda Mihelič in 2001, really only came about when Wettach’s remarkable villa in Ljubljana was acquired and renovated by the US Embassy, and not by actual interest in him or his work.8 He sometimes appears more prominently and in a more positive light in texts about the artist Elsa Kastl Obereigner in the role as her teacher. The catalogue for Kastl’s exhibition at Ljubljana City Museum in 2018 also includes a text by her granddaughter Angelika Hribar, who is in charge of family heirlooms that include a number of works and sources connected to Wettach, particularly his educational work.9

6Research by Slovenian musicologists plays an important part in understanding Wettach’s pursuits in Ljubljana, as their attitude to him or rather, the Philharmonic Society – the most eminent Ljubljana cultural institution at the time in which he was actively involved – was much more positive than by art history. Most probably the Philharmonics’ outstanding international importance prevented the society from sinking into oblivion despite its ties to the Carniolan German cultural circle. Among the research in which at least Wettach’s musical pursuits can be properly traced – as an official of the society and as a very active, albeit amateur musician – we must mention Primož Kuret’s study Ljubljanska filharmonična družba: 1794–1919 and Jernej Weiss's research, which resulted in the book Hans Gerstner (1851–1939): Življenje za glasbo.10

7The present article is the first in a series of four about the painter, with the second, forthcoming in the next issue of the same journal, while the following two will be published elsewhere and co-written with Miha Valant. The first co-authored article approaches Wettach through education; first, the education he received at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna as well as the education he provided by teaching visual arts in different secondary schools in Ljubljana and leading his own painting school.11 The second article with Valant focuses exclusively on the analysis of Wettach’s painting opus.12 Because a significant portion of the so-called ego-documents related to individuals and institutions mentioned in these articles is either missing, with unknown whereabouts, or has been lost or destroyed – a part of it probably intentionally during historic upheavals –,13 the individuals under discussion struggle to emerge as complex and nuanced characters, which makes misconceptions in presenting and interpreting their views, relationships and sometimes even key life decisions all the more likely.14 And yet, just as we can postpone our research of fine arts and culture of the German-leaning Carniolans ad infinitum, we can also approach it with the awareness that we have done the utmost possible, fully acknowledging that the first more serious personal correspondence that might appear has the power to undermine the established view of the forgotten artist and his world.

2. The Painter's Beginnings and Settling in Ljubljana

1Heinrich Ignaz Wettach was born in Vienna on 15 June 1858. His mother was a housewife and his father a manufacturer of templates for music sheets and bookkeeping ledgers (Rastrierer).15 According to his grandson Harald Wettach, Heinrich was not the firstborn but became the only child after an outbreak of cholera in Vienna in the 1860s. His brother Emmerich Wettach, who later became a high-school teacher in Brno, was born after the epidemic.16

Source: private collection

2Heinrich Wettach initially trained as a stationer (Papierhändler). Allegedly he was already successful professionally when he decided to continue his education at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, between 1880 and 1885. The fact that he won a scholarship indicates that the young student showed promise, although he did not receive any awards during his time at the academy.17 It is possible that during his studies he met some artists who lived in Carniola or were connected to it. For example, his contemporary at the academy was the Vienna Secession member Ernst Stöhr, who then spent lengthy periods living and working in Bohinj and had contacts with individuals from Ljubljana society that Wettach became part of.18 There were also several Carniolan students at the academy at the time, for example, Anton Ažbe, Ferdo Vesel and Josef Vesel. Wettach remained in close contact with the latter once he moved to Ljubljana; they collaborated on different events and activities and were very likely personal friends.19

3Wettach probably moved to Ljubljana when he completed his studies in 1885. The question is how he even decided on such a step and why. The answer can partly be found in the obituaries in the Carinthian papers Villacher Zeitung and Freie Stimmen. They claim that he travelled to Ljubljana with his friend, architect Julius Schmidt, who in 1886 designed the monument dedicated to the lauded poet and liberal politician, Ljubljana citizen Anton Alexander Count Auersperg (1806–1876, pen name Anastasius Grün) at the corner of his house. Therefore, both Wettach and Schmidt must have decided at least on a brief stay in the Carniolan capital.20

4Wettach’s grandson’s statements complement this story: according to him, after completing his studies his grandfather travelled around the monarchy searching for attractive motifs to paint. Whilst sitting in one of Ljubljana cafes, he overheard a discussion in which the participants moaned about being short of a fourth member of a string quartet. He offered to step in and thus remained in Carniola.21 The anecdote seems relatively plausible, because his collaboration with the Philharmonic Society and music – in addition to painting – soon reinforced Wettach’s place in the core of Ljubljana bourgeois society. As a musician, he regularly performed in public in Ljubljana, including with the best-known local string quartet at the time, which was led by the Philharmonic Society concert master, Hans Gerstner.22

5The most important factor contributing to Wettach’s settling in Carniola was probably that he quickly received commissions for portraits and other paintings. Wettach is first mentioned in Ljubljana media, Laibacher Zeitung in September 1885 – the “Viennese painter” (Wiener Maler) completed a portrait of the Ljubljana Sharpshooters’ Society president, the well-known Ljubljana merchant Emerik Mayer.23 The fact that this influential society commissioned work from him surely means that he quickly found contact with illustrious clients in Ljubljana, which soon included, for example, Bishop Jakob Missia and individuals from respectable Ljubljana families.24 The orders for portraits reveal that initially, in his first years in Carniola, he was still working for the entire spectrum of Ljubljana society, while in later decades, the orders came increasingly from the local German-leaning population.25

Source: private collection

6By the early 1890s, Wettach had consolidated his status as one of Ljubljana’s key artists willing to take on commissions. Reports in Ljubljana newspapers reveal that he designed diplomas and similar items for different local associations, communities and occasions, conceived tableaux vivants, organised and provided visuals for various public events, among them – although not until 1908 – a large Gottschee Germans parade float for the Carniolan part of the parade celebrating the Emperor’s jubilee in Vienna.26 He also tried to secure larger public commissions. In the early 1890s, he participated in the tender to decorate the premises of the new Carniola Provincial Theatre, but failed to get the job he was hoping for. He was, however, commissioned to paint four monumental paintings representing four symphony movements in the newly built hall of the Philharmonic Society.27

7We can assume that the young painter further strengthened his social position with an excellent marriage. Heinrich Wettach married Marie Antonia Hofmann (1872–1967) – the wealthy and educated daughter of a doctor, politician, landowner and art collector and connoisseur (particularly of graphic art) Julius Hofmann of Karlovy Vary in the Kingdom of Bohemia – at the Votive Church in Vienna on 4 May 1995.28 Marie joined her husband in Ljubljana, where as a sophisticated and very active townswoman, soon took on a very important social role. The Wettachs started their family very quickly and lived in a lavish household with many servants. The descendants’ narratives hint that the inequality in property and status clearly impacted the spouses and perhaps inauspiciously affected the young family, although we are not able to understand exactly how.29 The new social status very probably meant a change in the painter’s professional circumstances, but we can again only guess about specific impacts.

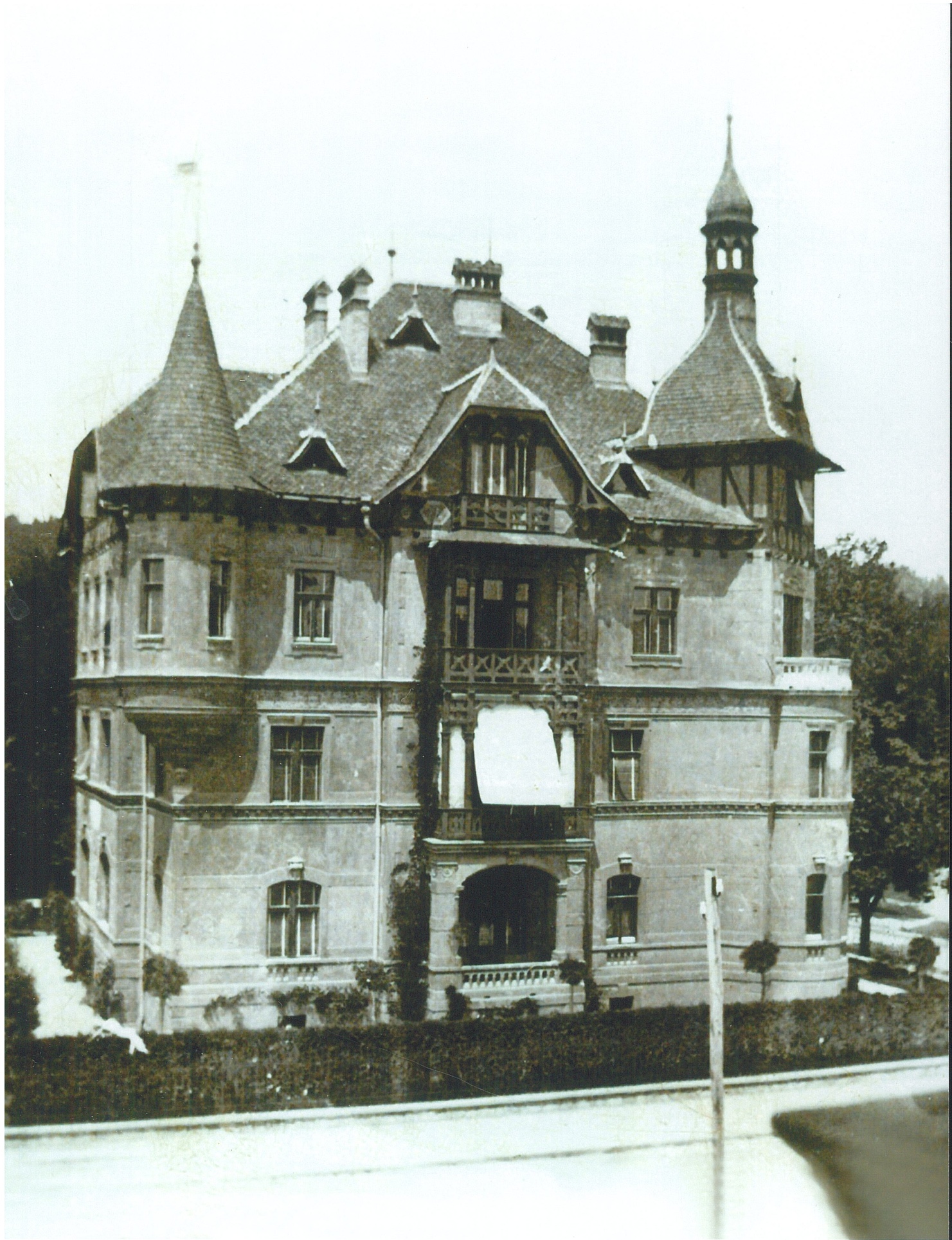

8In 1896/1897, the couple built a villa in today’s Prešernova street, known as “Villa Wettach” at the turn of the century and now as the “American Embassy”.

Source: private collection

9The plans were drawn up by architect Alfred Bayer who, like Wettach’s wife came from Karlovy Vary and was at the time a successful independent collaborator of the well-known Austrian architectural bureau Fellner and Hellmer. The villa was in fact an apartment building with the Wettach family apartment situated on the second floor and the rest let to tenants.30 The painter kept a studio in the house where he also ran his painting school. The house already drew attention during construction because it was too big for the location – the painter was fined for not meeting the criteria defined in the building permit. Its exterior was explicitly articulated, featuring characteristic projections and decorated with images in fresco and sgraffito techniques, allegedly made by Wettach himself.31

10The Wettachs built the neighbouring smaller villa with a very accentuated decorative imitation of Fachwerk (half-timber) construction (today Prešernova 29) around 1912.32 The decision to build another, smaller house next to the existing large two-storey villa was perhaps as an investment but based on the grandson’s words was due to the lack of space.33 This can perhaps be explained by the fact that the Wettachs’ original villa was indeed a very lively space. Not only were several flats let to tenants and the painter’s studio hosted his painting school, it was also a hub for socialising of a select social group and a venue for small concerts and regular music rehearsals. Fritz Zangger from Celje mentions in his memoirs that while staying in Ljubljana his string trio practised there every Saturday afternoon.34

11Similar to this smaller villa and around the same time, the family built their third house in Sankt Andrä on Lake Ossiach.35

12Heinrich and Marie Wettach spent their summer holidays at the Friulian seaside town of Grado and Lake Ossiach in Carinthia.36 The latter grew on them so much that they built their holiday home there, where they lived after moving to Carinthia in 1919. The house was most likely demolished in the 1960s.37

13All three Wettach houses, the two in Ljubljana and the one on Lake Ossiach, had at least part of their facades constructed in the typical half-timbered constructions (Fachwerk) or were decorated with an imitation of it. At the time, Fachwerk was said to be very popular among the German-leaning population in the nationally mixed territories of the monarchy and also a way to directly inscribe this national orientation into the space.38 The Wettachs’ first and largest villa had, following this spirit, an explicitly articulated façade with characteristic projections and its decorative elements, corner turrets, gabled roofing, all alluded to the German late Middle Ages or the Northern Renaissance.39 Because the Wettachs chose visual and architectural ways to publicly express that they saw Carniola as a part of the German cultural space, this also confirms our understanding of their political orientation and stance. They were not out of the ordinary in this and fitted in well with the general political events of the given moment as many others thought of their houses that way; for example, among the Slovenian-leaning Carniolans, Ljubljana Mayor Ivan Hribar with his “Slovenian” decorations on his holiday house in Cerklje.40

Source: private collection

14Wettach’s life trajectory in the Carniolan capital coincided with the period between the 1880s and World War I, which was marked by nationalism so intense that it completely permeated everyday life. At that time, such processes also occurred elsewhere in the monarchy with similar ethnic composition,41 and just around Wettach’s arrival in Ljubljana, led to the loss of dominance by the liberal Constitutional Party (Verfassungspartei, or Deutschliberale Partei) in the City Council and Provincial Diet (Landtag). This party tied its primary ideals and missions to the wider German space with German as the lingua franca; the ideals being a more integrated Austria, religious freedom and anti-church sentiments, emphasis on education and liberal reforms of the economy, etc. The takeover of the Carniolan government by Slovenian politicians led to the decisive introduction of the Slovenian language into the education system, in addition to administrative offices, while Slovenian national identification and nationalism increased throughout the province. This made the German-leaning population feel increasingly endangered, while the liberal Constitutional Party, the party of choice for a large part of the German-leaning Carniolans, experienced a slide from liberal principles to German nationalism as their primary political conviction. This process is also obvious from the declarative renaming of the remnants of the liberal Constitutional Party into the German Party in 1894.42

15National frictions in Carniola at that time were increasingly expressed through physical violence and vandalism. That included violent protests, such as the Slovenian protest at the unveiling of the previously mentioned monument to the politician and poet Anton Alexander von Auersperg, in 1886 – Heinrich Wettach attended as the choirmaster of the Turnverein. These were followed by the larger “anti-German” protests in 1898, 1903 and 1908.43 Slovenia chooses to “remember” the military intervention in the autumn of 1908 which resulted in two Slovenian deaths, while it “forgets” that for decades prior, the minority German-leaning community in Carniola experienced significantly more violence, from everyday harassment in public to boycotting German-leaning merchants and craftsmen and violating their property. Throwing stones at the windows of the liberal, and then German-leaning politicians was commonplace practice since the 1860s onwards, while during the 1908 unrest, everything from the Kazina Society Palace to schools and kindergartens were stoned.44

16Once we are aware of the radicality of this situation, it is perhaps easier to understand that – and how – the national battle in Ljubljana was also territorial and architectural, not just with institutional buildings but also with houses of important and wealthy individuals. When the Slovenian National Home (today’s National Gallery) was being built in the mid-1890s, the construction of Villa Wettach in its recognisably “German spirit” also began practically next door, and then, albeit as the artist’s private hospitable residence, it became one of the key music and visual arts or, more generally, cultural centres of the German-leaning Ljubljana citizens. A few years later, Jakopič Pavillion – the first independent exhibition venue intended for visual arts in Carniola – was built in the immediate vicinity, presumably at least partly to counterbalance these events, and with far more municipal support – the mayor at the time being the previously mentioned strongly Slovenian and Slavic oriented Ivan Hribar – than we can prove today.45 At least from the late 1890s onwards, the majority of new buildings in the city centre thus had some kind of recognisable national orientation, whether it was visual in their façades or not, and that included schools or even churches, such as the “Slovenian” Mladika [female lycée] and the “German” Evangelical church located near Wettach’s Villa.46 In this sense, buildings alternated in this part of town at the turn of the century, and in some of them years-long, vicious battles took place for them to be perceived as one or the other. For example, despite pressure the Provincial Museum generally remained focused on presenting local Carniolan, that is nationally indetermined culture, while the intense and unrelentless national battle for governance over the new joint national theatre resulted in it becoming Slovenian and a new theatre for the German-leaning community being built elsewhere.47 There were numerous examples at that time, and to round up we can use the memories of Wettach’s eldest daughter about how she would play in the nationally segregated Tivoli park. Or how schoolchildren based on their nationality walked on separate sides of the street to prevent riots – German-leaning children on one side, and Slovenian-leaning children on the other – taunting each other relentlessly with signs or symbols in either German or Slavic colours.48

17That Wettach was a newcomer to the Carniolan territory at the time of great political and national(ist) hostilities probably influenced his identity. Perhaps he was already a German nationalist when he arrived in Carniola. Perhaps he developed, or at least consolidated this position when as a non-Slovenian speaking new-comer he quite logically joined the circles of the German-leaning Ljubljana community, at the time of great endangerment and homogenisation. In any case, by the end of the century at the latest, he began to feel more German, or based on available sources, he started to express it more pronouncedly. For example, Vienna academy registers list his religious affiliation as Catholic during his studies there, while later Ljubljana censuses show that he, as pointed out in the introduction, together with his family (wife Marie, daughters Brigitte and Irmgard and son Reinhardt Friederich) converted to Protestantism.49 The decision to take this step can be understood as a declarative political gesture linked to the Away From Rome! movement, which was gaining momentum in some nationally mixed territories of Austria.50 We can only guess what consequences this very unlikeable gesture had on him and his family in the Catholic environment of Carniola.51

18Wettach also began to actively participate in the provincial politics and, for example ran on the list of the German party in the 1899 municipal elections. In 1906, Slovenec newspaper mentions him as one of the initiators of the idea of self-representation of the so-called Carniolan Germans in the parliament in Vienna.52 Here, we can add that in Carniola national(istic) movements on both sides often reflected similar currents to those in Bohemia, where because of local specifics, conflicts were more pronounced.53 Wettach was no doubt familiar with the situation through his wife Marie, who was from there and was a very active participant in Ljubljana’s German protective societies (Schützvereine).

Sources and literature

- SI ZAL – Zgodovinski arhiv Ljubljana:

- SI ZAL LJU/0500, City of Ljubljana, local history department, census forms.

- Universitätsarchiv der Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien:

- Matrikel II. 1883/84.

- Wettach, Heinrich (Ignaz), Verz.-Einheits-Formular.

- Bučič, Vesna. “Elza Obereigner Kastl – naša poslednja miniaturistka.ˮ In: Barbara Jaki, ed. Razprave iz evropske umetnosti. Za Ksenijo Rozman, 285–323. Ljubljana: Narodna galerija, 1999.

- Cankar, Tadej.Odločnejši protivniki semitstva: O antisemitizmu in slovenskih liberalcih na Kranjskem. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino and Arhiv Republike Slovenije, 2023.

- Cohen B., Garry. The Politics of Ethnic Survival: Germans in Prague, 1861–1914. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 2006.

- Cvirn, Janez. “Kdor te sreča, naj te sune, če ti more, v zobe plune.ˮ Zgodovina za vse 14, No. 2 (2007): 38–56.

- Cvirn, Janez. Trdnjavski trikotnik: Politična orientacija Nemcev na Spodnjem Štajerskem (1861–1914). Maribor: Založba Obzorja Maribor, 1997.

- Henig Miščič, Nataša. “Carniolan Savings Bank and Slovenian-German Relations in 1908 and 1909.ˮ Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino, 15, No. 1 (2020): 47–70.

- Hribar, Angelika. “Življenjepis Elze Kastl Obereigner.ˮ In: Barbara Savenc, ed. Elza Kastl Obereigner (1884–1973). Kiparka in slikarka, 10–35. Ljubljana; Muzej in galerije mesta Ljubljana, 2018.

- Hribar, Ivan. Moji spomini I, II. Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 2022.

- Friedrich Keesbacher. ed. Jahres-Bericht der philharmonischen Gesellscahft in Laibach: für die Zeit vom 1. Oktober 1885 bis 30. September 1886. Laibach: Verlag der philharmonischen Gesellschaft, 1886.

- Jenko, Sandra. Jubilejno gledališče cesarja Franca Jožefa v Ljubljani: Zgodovina nastanka in razvoj nemškega odra med 1911 in 1918. Ljubljana: Slovenski gledališki muzej, 2013.

- Jezernik, Božidar. “Ljubljanski »tempelj znanosti« v vrtincu kulturnega boja.ˮ Argo 54, No. 1 (2011): 26–40.

- Jezernik, Božidar. Mesto brez spomina. Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2014.

- Judson M., Pieter. “Versuche um 1900, die Sprachgrenze sichtbar zu machen.ˮ In: Moritz Csáky and Peter Stachel, eds. Die Verortung von Gedächtnis, 163–174. Wien: Passagen Verlag, 2001.

- Judson M., Pieter. Guardians of the Nation: Activists on the Language Frontiers of Imperial Austria. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Kavrečič, Petra. “Biseri avstrijske riviere: Opatija, Gradež, Portorož.ˮ Kronika 57 (2009): 113–128.

- Kosi, Jernej. Kako je nastal slovenski narod: Začetki slovenskega nacionalnega gibanja v prvi polovici 19. stoletja. Ljubljana: Sophia, 2013.

- Kupferstichsammlung Dr. Julius Hofmann: Wien (auction catalogue, Leipzig, 1922).

- Kuret, Primož. “Jubilejna koncertna sezona 1901–1902 Ljubljanske filharmonične družbe.ˮ Muzikološki zbornik 19, (1983): 41–50.

- Kuret, Primož. Ljubljanska filharmonična družba 1794–1919: Kronika ljubljanskega glasbenega življenja v stoletju meščanov in revolucij. Ljubljana: Nova revija, 2005.

- Lazarini, Franci. “Nacionalni slogi kot propagandno sredstvo prebujajočih se narodov: Slovenski in drugi nacionalni slogi v arhitekturi okoli leta 1900.ˮ Acta Historiae Artis Slovenica 25, No. 2 (2020): 249–67. https://doi.org/10.3986/ahas.25.2.10.

- Matić, Dragan. Nemci v Ljubljani: 1861–1918. Ljubljana: Oddelek za zgodovino Filozofske fakultete, 2003.

- Mihelič, Breda. “Vilska četrt med Prešernovo cesto in Tivolijem v Ljubljani ter prenova Wettachove vile: Problemi varovanja in prenove stanovanjske četrti.ˮ Varstvo spomenikov 39 (2003): 139–49.

- Photographische Correspondenz (januar 1913), 291–292. “Dr. Julius Hofmann.ˮ

- Pollack, Martin. Smrt v bunkerju: Poročilo o mojem očetu. Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 2005.

- Ratej, Mateja. Svastika na pokopališkem zidu: Poročilo o hitlerizmu v širši okolici Maribora v tridesetih letih 20. stoletja. Ljubljana: Beletrina, 2021.

- Sapač, Igor and Franci Lazarini. Arhitektura 19. stoletja na Slovenskem. Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje in Fakulteta za arhitekturo, 2015.

- Strle, Urška and Beti Žerovc. “The painter Ivana Kobilca and her use of social networks.ˮ In: Marta Verginella, ed. Women, nationalism, and social networks in the Habsburg monarchy. 1848-1918, 163–95. West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 2023.

- Studen, Andrej. “Nekaj sledi iz življenja ravnateljev Kranjskega deželnega muzeja.ˮ Argo 46, No. 1 (2003): 9–14.

- Tessmar, Catherine. Wiener Platzerln: Die Geschäfte des Künstlers Luigi Kasimir. Wien: Czernin, 2006.

- Trauner, Karl-Reinhart. “Los von Rom, aber nicht Hin zum Evangelium – Die Los von Rom-Bewegung in Tirol.ˮ Jahrbuch für die Geschichte des Protestantismus in Österreich 123 (2007): 120–70.

- van der Wal, Marijke J. in Gijsbert Johan Rutten. Touching the Past: Studies in the Historical Sociolinguistics of Ego-documents. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Company, 2013.

- Valant, Miha. “Ljubljansko društvo Kazina in združenja za likovno umetnost na Kranjskem med leti 1848 in 1918.ˮ Doctoral dissertation, University of Ljubljana, 2023.

- Valant, Miha and Beti Žerovc. “Društva za likovno umetnost na Kranjskem v obdobju od 1848 do 1918.ˮ Likovne besede, No. 113 (2019): 4–13.

- Weiss, Jernej. Hans Gerstner. (1851–1939): Življenje za glasbo. Maribor: Litera and Pedagoška fakulteta, 2010.

- Wingfield, Nancy M. Flag Wars and Stone Saints: How the Bohemian Lands Became Czech. Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Zangger, Fritz. Das ewige Feuer im fernen Land. Ein deutsches Heimatbuch aus dem Südosten. Cilli, 1937.

- Žerovc, Beti. “Vesna ob izviru umetnosti.” In: Barbara Borčič and Jure Mikuž, eds. Potlačena umetnost, 50–77. Ljubljana: Open Society Institute, 1999.

- Žerovc, Beti. Slovenski impresionisti. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 2012.

- Žerovc, Beti. “Ivan Meštrović and the Vesna Society.ˮ Život umjetnosti 113, No. 2 (2023): 146–63.

- Žerovc, Beti. “The Development of Public Monuments and Monuments to the Fallen on the Territory of Yugoslavia form the Late 19th Century to 1941.ˮ In: Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc, eds. Shaping Revolutionary Memory: The Production of Monuments in Socialist Yugoslavia, 20–57. Berlin: Archive Books; Ljubljana: Društvo Igor Zabel za kulturo in teorijo, 2023.

- Žerovc, Beti. “Ivan Meštrović u Ljubljani 1903./1904.: Prijedlozi za dva spomenika i izlaganje s društvom Hagenbund u ljubljanskoj kazini.ˮ Časopis za suvremenu povijest 56, no. 2 (2024): 249–77.

- Žerovc, Beti and Miha Valant. “The Artistic Formation of the Painter Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929) and His Educational Work” (forthcoming).

- Žerovc, Beti and Miha Valant. “The Artistic Legacy of Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929)” (forthcoming).

- Žerovc, Beti. “Cultural and Historical Overview of the Life of the Painter Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929), II.; The Artist’s Engagement in Ljubljana Social Life and Societies and His Final Years in Carinthia.” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 65, no. 3 (2025) (forthcoming).

- Besuch von Erzherzog Karl bei der Kärntner Landesausstellung at 2'50''. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z063um-BW9U&t=6s).

- Deutsche Wacht, 1886.

- Die Zeit, 1913.

- Freie Stimmen, 1929.

- Kärntner Tagblatt, 1912.

- Laibacher Wochenblatt, 1889, 1892.

- Laibacher Zeitung, 1885, 1887, 1891, 1892, 1894, 1899, 1907, 1908, 1909.

- Neue Freie Presse, 1913.

- Slovenec, 1886, 1891, 1906.

- Villacher Zeitung, 1911, 1929.

- Wiener Landwirtschaftliche Zeitung, 1894.

- Zarja, 1912.

- Harald Wettach, semi-structured interviews by Beti Žerovc, 2012.

- Brigitta Leitenberger, semi-structured interview by Ruth Deutschmann, 1998. The Austrian director Deutschmann conducted the interview as part of the Chronisten project (https://chronisten.at/).

Beti Žerovc

KULTURNOZGODOVINSKI ORIS ŽIVLJENJA SLIKARJA HEINRICHA WETTACHA (1858–1929), I.; ZAČETKI IN USTALITEV SLIKARJA V LJUBLJANI

POVZETEK

1Osrednji namen članka je podati kratko študijo o življenju, delovanju in širši družbeni vpetosti slikarja Heinricha Wettacha (1858–1929), ki je deloval v Ljubljani od leta 1885 do konca prve svetovne vojne, ter ga s tem konkretneje usidrati tudi v kulturni milje kranjske prestolnice na prelomu stoletja. Ne glede na to, da je s svojim slikarskim in hkrati tudi aktivnim glasbenim delovanjem v skoraj štirih desetletjih pustil močan pečat na kranjski kulturi in družbi ter da je bil v svojem času vsekakor tudi eden najbolj prepoznavnih ljubljanskih kulturnikov, je namreč danes skoraj neznan. V članku poskušam že tudi osvetliti, zakaj je tako, pri čemer igrata ključno vlogo pri umetnikovem spregledovanju v slovenski umetnostni zgodovini njegova politična drža in pripadnost nemško čutečemu kranjskemu kulturnemu krogu.

2Po doslej opravljenih raziskavah se kaže, da bi Heinricha Wettacha – v širokem spektru kranjskega nemško čutečega prebivalstva – verjetno najustrezneje uvrstili k t. i. nemškim nacionalcem. Da bi bolje in v kontekstu razumeli umetnikovo nemštvo, so v članku nekoliko bolj poudarjeni nekateri vidiki, na podlagi katerih je to dobro berljivo, denimo specifičen videz treh novozgrajenih hiš družine Wettach ter prestop umetnika in njegove družine iz katoliške v protestantsko vero. Razprava po eni strani poskuša vsaj delno rekonstruirati življenjsko pot in nazore spregledanega umetnika v slovenski umetnostni zgodovini, po drugi strani pa tudi delček zgodovine, brez katerega poznavanje in razumevanje slovenske likovne umetnosti in kulture na prelomu stoletja preprosto ne moreta biti celovita.

* The article is funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) as a part of the research program P6-0199 History of Art of Slovenia, Central Europe and the Adriatic.

** Dr., izredna profesorica, Oddelek za umetnostno zgodovino Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani, Aškerčeva 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Beti.Zerovc@ff.uni-lj.si

1. For the context of the issues in the broader space of Austria-Hungary, see Pieter M. Judson, “Versuche um 1900, die Sprachgrenze sichtbar zu machen,ˮ in: Moritz Csáky and Peter Stachel, eds., Die Verortung von Gedächtnis (Wien: Passagen Verlag, 2001), 163–174 . Pieter M. Judson, Guardians of the Nation: Activists on the Language Frontiers of Imperial Austria (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 19–65. For issues explained in the context of Carniola, see Dragan Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani: 1861–1918 (Ljubljana: Oddelek za zgodovino Filozofske fakultete, 2003). Janez Cvirn, “Kdor te sreča, naj te sune, če ti more, v zobe plune,ˮ Zgodovina za vse 14, No. 2 (2007): 38–56. Jernej Kosi, Kako je nastal slovenski narod: Začetki slovenskega nacionalnega gibanja v prvi polovici 19. stoletja (Ljubljana: Sophia, 2013). Miha Valant, “Ljubljansko društvo Kazina in združenja za likovno umetnost na Kranjskem med leti 1848 in 1918ˮ (Doctoral dissertation, University of Ljubljana, 2023). In the context of contemporary Slovenian historiography some very important studies on the life and attitudes of German-leaning Styrians were carried out by Janez Cvirn, particularly his book Trdnjavski trikotnik: Politična orientacija Nemcev na Spodnjem Štajerskem (1861–1914) (Maribor: Založba Obzorja Maribor, 1997).

2. To compare, see the attempt to define the national identity of Wettach’s contemporary, Carniolan painter Ivana Kobilca in Urška Strle and Beti Žerovc, “The painter Ivana Kobilca and her use of social networks,ˮ in: Marta Verginella, ed., Women, nationalism, and social networks in the Habsburg monarchy: 1848-1918 (West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 2023), 163–195, particularly 167–174. For the processes of German-leaning Styrians and Carniolans sliding towards German nationalism and then also Nazism in the 20th century, see Mateja Ratej, Svastika na pokopališkem zidu: Poročilo o hitlerizmu v širši okolici Maribora v tridesetih letih 20. stoletja (Ljubljana: Beletrina, 2021) and a poignant reconstruction of the lives of family members of the writer, journalist and long-time editor of the magazine Der Spiegel Martin Pollack, whose paternal grandmother was from Ljubljana and his grandfather from Laško. Martin Pollack, Smrt v bunkerju: Poročilo o mojem očetu (Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 2005). For the artistic trajectory of a German-leaning Styrian from Ptuj, the internationally established graphic artist and an active nazi Luigi Kasimir, see Catherine Tessmar, Wiener Platzerln: Die Geschäfte des Künstlers Luigi Kasimir (Wien: Czernin, 2006).

3. See also footnote 50. On political positions and religious, and particularly national identification of artists at this time, one should always consider them through the prism of pragmatism, as nationalism at that time influenced the increase in commissions and awarding them to artists exclusively on a national basis. See Beti Žerovc, “The Development of Public Monuments and Monuments to the Fallen on the Territory of Yugoslavia from the Late 19th Century to 1941,ˮ in: Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc, eds., Shaping Revolutionary Memory: The Production of Monuments in Socialist Yugoslavia (Berlin: Archive Books and Ljubljana: Društvo Igor Zabel za kulturo in teorijo, 2023), 28, 29.

4. On antisemitism among the Slovenian-leaning Carniolans see Tadej Cankar, Odločnejši protivniki semitstva: O antisemitizmu in slovenskih liberalcih na Kranjskem (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino and Arhiv Republike Slovenije, 2023), 76–165.

5. Even today, we often fail to see that something labelled Slovenian at the time might have been arbitrary, let alone perceive it as aggressive or polarising. As a rule, it is perceived as something neutral, and above all, natural. Hribar’s attitude to these aspects is clear from his memoirs. Ivan Hribar, Moji spomini I, II (Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 2022). For the Vesna Society, see Beti Žerovc, “Vesna ob izviru umetnosti,” in: Barbara Borčič and Jure Mikuž, eds., Potlačena umetnost (Ljubljana: Open Society Institute, 1999), 50–77. Beti Žerovc, “Ivan Meštrović and the Vesna Society,ˮ Život umjetnosti 113, No. 2 (2023): 146–163. Beti Žerovc, “Ivan Meštrović u Ljubljani 1903/1904: Prijedlozi za dva spomenika i izlaganje s društvom Hagenbund u ljubljanskoj kazini,ˮ Časopis za suvremenu povijest 56, No. 2 (2024): 249–277.

6. Musicologist Kuret describes a similar situation in his field. Primož Kuret, “Jubilejna koncertna sezona 1901–1902 Ljubljanske filharmonične družbe,ˮ Muzikološki zbornik 19, (1983): 43, 47, 48. See also Beti Žerovc, “Cultural and Historical Overview of the Life of the Painter Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929), II.; The Artist’s Engagement in Ljubljana Social Life and Societies and His Final Years in Carinthia,” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 65, no. 3 (2025, forthcoming), fn. 43.

7. Currently, there are seventeen works by Wettach or attributed to him at the National Museum of Slovenia, eleven at the National Gallery, seventeen in the Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana and one in the Upper Sava Valley Museum, Jesenice.

8. Breda Mihelič, “Vilska četrt med Prešernovo cesto in Tivolijem v Ljubljani ter prenova Wettachove vile: Problemi varovanja in prenove stanovanjske četrti,ˮ Varstvo spomenikov 39 (2001): 139–149. He was presented in the artistic context of Carniola at the turn of the century by Beti Žerovc, Slovenski impresionisti (Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 2012), 71–73. For the events and activities of the Kazina circle in Ljubljana, the most thorough Wettach presentation is by Miha Valant in Valant, “ Ljubljansko društvo Kazina,ˮ189–213, 300–302 et passim. For more about his extensive opus and for the review of his artistic conservativism, which also had a negative effect on the professional research of him, see Beti Žerovc and Miha Valant, “The Artistic Legacy of Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929),” (forthcoming).

9. Angelika Hribar, “Življenjepis Elze Kastl Obereigner,ˮ in: Barbara Savenc, ed., Elza Kastl Obereigner (1884–1973). Kiparka in slikarka (Ljubljana: Muzej in galerije mesta Ljubljana, 2018), 10–35. See also Vesna Bučič, “Elza Obereigner Kastl – naša poslednja miniaturistka,ˮ in: Barbara Jaki, ed., Razprave iz evropske umetnosti. Za Ksenijo Rozman (Ljubljana: Narodna galerija, 1999), 285–323.

10. Primož Kuret, Ljubljanska filharmonična družba 1794–1919: Kronika ljubljanskega glasbenega življenja v stoletju meščanov in revolucij (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 2005). Jernej Weiss, Hans Gerstner. (1851–1939): Življenje za glasbo (Maribor: Litera in Pedagoška fakulteta, 2010).

11. Beti Žerovc and Miha Valant, “The Artistic Formation of the Painter Heinrich Wettach (1858–1929) and His Educational Work,ˮ (forthcoming).

12. “Žerovc and Valant, “The Artistic Legacy.ˮ

13. See, for example, Weiss, Hans Gerstner, 72–74, 164, 165. Strle and Žerovc, “The painter Ivana Kobilca,ˮ 166, 167.

14. “Ego-document” refers to an autobiographical text, usually in the first person. It can be a journal, a memoir, correspondence, notes or similar, that can also be conveyed in a conversational style. For more, see Marijke J. van der Wal and Gijsbert Johan Rutten, Touching the Past: Studies in the Historical Sociolinguistics of Ego-documents (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Company, 2013). Strle and Žerovc, “The painter Ivana Kobilca,ˮ 164–67.

15. Register II. 1883/84 (Matr.-Bd. 113), Universitätsarchiv der Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien. Harald Wettach, semi-structured interview by Beti Žerovc, 2012.

16. Harald Wettach, semi-structured interviews by Beti Žerovc, 2012; Obituary “Georg Franz Wettach,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CXXVIII/214, 20 September 1909, 1922. Two of Wettach siblings were said to have died during the cholera outbreak, which Heinrich Wettach’s daughter, Brigitta Leitenberger, confirmed. Brigitta Leitenberger, semi-structured interview by Ruth Deutschmann, 1998. The Austrian director conducted the interview as part of the Chronisten project (https://chronisten.at/).

17. Wettach, Heinrich (Ignaz), Verz.-Einheits-Formular, 2022, Universitätsarchiv der Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien. For more on Wettach’s studies, see Žerovc and Valant, “The Artistic Formation.ˮ

18. One of his correspondents and friends was the painter Elsa Kastl. See Bučič, “Elza Obereigner Kastlˮ; Žerovc and Valant, “The Artistic Formation.ˮ

19. Ibid. Considering the data collected we can assume that Wettach and Vesel very likely met as students but we do not know if (and how much) this acquaintance influenced Wettach settling in Ljubljana.

20. Dr. B [inder?], “Heinrich Wettach,ˮ Villacher Zeitung, XXVII/82, 12 October 1929, 5. “Zum Tode Heinrich Wettachs,ˮ Freie Stimmen, XLIX/238, 15 October 1929, 6. An extensive obituary signed by “dr. B,” which could have been Josef Julius Binder, once an active member of the Ljubljana Turnverein, who knew Wettach well and like him lived in Carinthia (Villach) after World War I. – Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 402. The obituary in Villacher Zeitung claims that he travelled to Ljubljana already in 1884.

21. Harald Wettach, semi-structured interviews by Beti Žerovc, 2012.

22. Weiss, Hans Gerstner, 46, 137, 138, 141, 146, 163, 164. Wettach appears regularly in annual reports of the Philharmonic Society’s activities. Forty-two volumes are accessible in the Digital Library of Slovenia (dLib).

23. “Laibacher Rohrschützen-Gesellschaft,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CIV/214, 21 September 1885, 1735. The portrait is now in the collection of Ljubljana City Museum.

24. “Občni zbor denarne obrtnijške družbe,ˮ Slovenec, 106, 11 May 1886, n. pag.; “Familienabend des Laibacher deutschen Turnvereines,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CVI/99, 3 May 1887, 836; “Die Section »Krain« des deutschen und österreichischen Alpenvereines,ˮ Laibacher Wochenblatt, 451, 30 March 1889, n. pag.; “Excursion des krainisch-küstenlandischen Forstvereines,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CXI/202, 5 September 1892, 1743; “Philharmonische Gesellschaft,ˮ Laibacher Wochenblatt, 597, 16 January 1892, n. pag.; “Ehrungskneipe,ˮ Laibacher Wochenblatt, 604, 5 March 1892, n. pag.; “Die Comeniusfeier des krainischen Lehrervereins,ˮ Laibacher Wochenblatt, 610, 16 April 1892, n. pag.; “Porträts,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CXIII/10, 13 January 1894, 80.

25. Žerovc and Valant, “The Artistic Legacyˮ

26. Ibid. The article also discusses the painter’s close relationship with the Gottschee Germans community; this could have been because the region around Kočevje/Gottschee was an island of German population within Carniola. “Das Schulvereinsfest in Gottschee,ˮ Laibacher Wochenblatt, 632, 17 September 1892, n. pag.; “Ehrung,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CXIII/174, 1 August 1894, 1487; “Ehrenbürgerdiplom,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CXXVI/288, 14 December 1907, 2698; “Vorbereitungen zum Wiener Festzug, Laibacher Zeitung,ˮ CXXVII/120, 25 May 1908, 1132.

27. “Novo deželno gledišče,ˮ Slovenec, 161, 18 July 1891, n.pag.; “Zum Theaterbau,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CX/170, 29. July 1891, 1418; “Die festliche Eröffnung der 'Tonhalle,'ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CX/245, 27 October 1891, 2047. More about it in Žerovc and Valant, “The Artistic Legacy.ˮ

28. Based on the descendants’ narrative and the mention of the father in the engagement announcement, we can assume that the bride’s father was Julius Emanuel Hofmann (1840–1913), who later lived in Vienna. “Verlobungsanzeige,ˮ Wiener Landwirtschaftliche Zeitung, XLIV/54, 7 July 1894, 458; “Dr. Julius Hofmann,ˮ Neue Freie Presse, 17500, 24 May 1913, 10. More about his art history expertise and collecting see in: “Dr. Julius Hofmann,ˮ Photographische Correspondenz, (January 1913), 291–292; Kupferstichsammlung Dr. Julius Hofmann: Wien (auction catalogue, Leipzig, 1922). Leitenberger states that also her mother’s grandfather was a physician in Karlovy Vary, even Otto von Bismarck’s personal physician. Brigitta Leitenberger, semi-structured interview by Ruth Deutschmann, 1998.

29. Both the daughter and the grandson mentioned how wealthy the mother was, and at the same time underlined the economic inequality of the couple. Brigitta Leitenberger, semi-structured interview by Ruth Deutschmann, 1998; Harald Wettach, semi-structured interviews by Beti Žerovc, 2012. Marie Wettach was also the owner of Villa Wettach. See Andrej Studen, “Nekaj sledi iz življenja ravnateljev Kranjskega deželnega muzeja,ˮ Argo 46, no. 1 (2003): 12, 13.

30. Ibid. Studen presents in detail the tenant situation in Villa Wettach and some of the tenants. Hans Gerstner remembers his family staying in the villa: “On 1 November 1904 we left the beautiful flat in Ljubljana, because Mr. Peter Schleimer wanted 650 kroner rent for it. We moved to an even nicer flat in Villa Wettach with a bathroom and the use of the garden. The four rooms were somewhat smaller, but on the sunny side and overlooking the garden and Tržaška street, and we paid 550 kroner per year.” Weiss, Hans Gerstner, 149.

31. More about the house in: Mihelič, “Vilska četrt,ˮ 142–144; Franci Lazarini, “Nacionalni slogi kot propagandno sredstvo prebujajočih se narodov: Slovenski in drugi nacionalni slogi v arhitekturi okoli leta 1900,ˮ Acta Historiae Artis Slovenica 25, no. 2 (2020): 262–264, https://doi.org/10.3986/ahas.25.2.10; Brigitta Leitenberger, semi-structured interview by Ruth Deutschmann, 1998.

32. “Letošnja stavbinska sezija v Ljubljani,ˮ Zarja, II/225, 12 April 1912, n. pag. The villa is now a kindergarten.

33. Harald Wettach, semi-structured interviews by Beti Žerovc, 2012.

34. Fritz Zangger, Das ewige Feuer im fernen Land: Ein deutsches Heimatbuch aus dem Südosten (Cilli, 1937), 91.

35. Harald Wettach, semi-structured interviews by Beti Žerovc, 2012. In 1911, Villacher Zeitung reported that the Wettach family bought the single-family house at the Carinthian Crafts Exhibition (Kärntner Landes-Handwerker-Ausstellung) in Klagenfurt and had it built in St. Andrä on Lake Ossiach. “Das Einfamilienhaus,ˮ Villacher Zeitung, IX/121, 15 October 1911, 7. It is most likely the house seen in a short film Besuch von Erzherzog Karl bei der Kärntner Landesausstellung at 2'50'' (Accessed 22 April 2021: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z063um-BW9U&t=6s).

36. Harald Wettach, semi-structured interviews by Beti Žerovc, 2012. Numerous forms of short-term mobility, which, in addition to visiting friends and family, included holidaying, excursions and recreation in nature were typical of the Austrian bourgeoisie of the late 19 th century. Such holiday-making and splitting holidays into mountain and seaside segments were relatively common among wealthier Carniolans as well. They often holidayed in Upper Carniola or Carinthia; two popular locations were for example, Lake Bled and Lake Wörth and their surroundings. They also enjoyed visiting spas, particularly Rogaška Slatina, and coastal resorts such as Opatija, Grado and others. – Petra Kavrečič, “Biseri avstrijske riviere: Opatija, Gradež, Portorož,ˮ Kronika 57, (2009): 113–128. They liked to organise different social events during such holidays. For instance, Wettach together with Hans Klein was asked by the local Landskron Verschönerungsverein (beautification society) to decorate the garden salon for a fancy dress ball at the Schöffmann Inn in St. Andrä on Lake Ossiach. (“Maskenball,ˮ Kärntner Tagblatt, XIX/197, 30 August 1912, 4). A similar event a year later expressed the theme “a night in Italy” (“St. Andrä am Ossiacher See,ˮ Die Zeit, XII/3927, 31 August 1913, 18). Cf. Strle and Žerovc, “The painter Ivana Kobilca,ˮ 186–187.

37. Harald Wettach, semi-structured interviews by Beti Žerovc, 2012.

38. Mihelič, “Vilska četrt,ˮ 142. Igor Sapač and Franci Lazarini, Arhitektura 19. stoletja na Slovenskem (Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje in Fakulteta za arhitekturo, 2015), 72, 73 et passim. Lazarini, “Nacionalni slogi,ˮ 262–64.

39. Today, portraying national spirit in buildings might be difficult to comprehend. Built a little later, the German House in Celje is an even clearer, and thus easier to understand example of politicised architectural expression. Sapač and Lazarini, Arhitektura 19. stoletja, 387. For more about the phenomenon, see Lazarini, “Nacionalni slogi.ˮ

40. Ibid., 255. Sapač and Lazarini, Arhitektura 19. stoletja, 392.

41. Comparative materials are quoted in the footnotes 1, 2 and 53.

42. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 25–32, 60–65, 75–89, 105–112, 197–232, 266–274, 299–301 et passim.

43. Božidar Jezernik, Mesto brez spomina (Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2014), 74–103. About Wettach's participation at the unveiling of a monument – “Die Anastasius-Grün-Feier in Laibach,ˮ Deutsche Wacht, XI/45, 6 June 1886, 3.

44. Jezernik, Mesto brez, 283–294. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 45–57, 92, 93, 234–236, 264–66, 310–18, 323, 333, 345–54 et passim.

45. Miha Valant and Beti Žerovc, “Društva za likovno umetnost na Kranjskem v obdobju od 1848 do 1918,ˮ Likovne besede, no. 113 (2019): 11, 12.

46. We are talking about the corner of the erstwhile Knaflova and Bleiweissova Streets (today’s Tomšičeva and Prešernova Streets) where villa Wettach stands and its immediate surroundings. Perhaps contrary to expectations, schools were particularly heavily biased in this way, because the language of instruction was often at the very core of disputes in ethnically mixed environments. Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 274–286, 373 et passim.

47. Sandra Jenko, Jubilejno gledališče cesarja Franca Jožefa v Ljubljani: Zgodovina nastanka in razvoj nemškega odra med 1911 in 1918 (Ljubljana: Slovenski gledališki muzej, 2013). Walter Šmid, an archaeologist who insisted on nationally undetermined culture at the Provincial Museum of Carniola – after he left his monastic order and the Catholic Church, converted to Protestantism and married – lost his directorial post in 1909 despite his expertise. Božidar Jezernik, “Ljubljanski ‘tempelj znanosti’ v vrtincu kulturnega boja,ˮ Argo 54, no. 1 (2011): 26–40. Šmid was probably a tenant at Villa Wettach for a while. Studen, “Nekaj sledi,ˮ 13–14. About the politically staged destruction of the Carniolan Savings Bank, the key sponsor organisation of the culture of German-leaning Carniolans that supported a number of art and crafts projects throughout the region, see Nataša Henig Miščič, “Carniolan Savings Bank and Slovenian-German Relations in 1908 and 1909,ˮ Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 15, No. 1 (2020): 47–70.

48. Brigitta Leitenberger, a semi-structured interview by Ruth Deutschmann, 1998. See also Beti Žerovc, “Cultural and Historical, II.,” fn. 43. Such orientation was visible even in clothing and later selection of accessories in national colours, or with added tricolours, became a profitable marketing niche. See, Matić, Nemci v Ljubljani, 234, 311 et passim. Anything could present national orientation, from selecting first names to the breed of pets. The Wettachs allegedly owned a “German” Great Dane. Brigitta Leitenberger, a semi-structured interview by Ruth Deutschmann, 1998. The Slovenian-leaning Carniolans were known to name their dogs after unpopular politicians from the opposing side. Even Ljubljana Seminary had a dog called Dežman, named after the German-leaning passionate Carniolan liberal, who even served a couple of years as Ljubljana mayor! Janez Cvirn, “Kdor te sreča,ˮ 44.

49. Census forms from the collection SI_ZAL_LJU/0500 City of Ljubljana, local history department, MF-415, MF-728. Brigitta Leitenberger explained that her father was not religious and probably estranged from the Catholic Church even before converting. “ Father literally never went to church, and Mother neither. We went to children’s service by ourselves, and I do not remember ever going to church on Sunday with our parents. Father certainly didn’t.” Brigitta Leitenberger, a semi-structured interview by Ruth Deutschmann, 1998.

50. The Away from Rome! (Los von Rom) movement was an anti-clerical conservative movement linked to the history of the creation of the German Empire and the question of the inclusion and role of Austria in this union. It took impetus from Badeni's language reform of 1897, which stipulated that administrators in Bohemia were required to speak German and Czech and was met with much opposition by German nationalists, while the Czech Catholic parties supported it. As a reaction to this, with encouragement from German nationalists, an anti-Catholic movement was formed under the leadership of Georg von Schönerer, and in addition to the stated objective it was also hostile to Judaism. In 1901, it adopted a resolution that determined that the programme of the movement was political and not of a religious nature. The movement thus had a pronounced atheist connotation and the protestant faith was used as a symbol of the “true” German spirit. Karl-Reinhart Trauner, “Los von Rom, aber nicht Hin zum Evangelium – Die Los von Rom-Bewegung in Tirol,ˮ Jahrbuch für die Geschichte des Protestantismus in Österreich 123 (2007): 126–28.

51. For speculations that this might have closed the door for him to teach in Carniolan secondary schools, see Žerovc and Valant, “The Artistic Formation.ˮ See also fn 46.

52. “Die Gemeinderathswahlen,ˮ Laibacher Zeitung, CXVIII/94, 25 April 1899, 735; “Kranjski Nemci pri Gautschu,ˮ Slovenec, 22, 27 January 1906, n. pag.

53. For comparison, we can list two studies of events in Bohemia: Garry B. Cohen, The Politics of Ethnic Survival: Germans in Prague, 1861–1914 (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 2006); Nancy M. Wingfield, Flag Wars and Stone Saints: How the Bohemian Lands Became Czech (Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press, 2007.