European Politics Behind Closed Doors: The Origins of Euroscepticism in Slovenia*

IZVLEČEK

NAŠA EVROPSKA POLITIKA ZA ZAPRTIMI VRATI: VZROKI EVROSKEPTIZICMA V SLOVENIJI

1Evroskpeticizem je eden najbolj perečih problemov tako držav članic Evropske unije, kot tudi držav v postopku približevanja EU. Splošno javno mnenje, zaradi katerega se med EU in njenimi prebivalci in prebivalkami pojavlja vedno večji razkorak, se giblje v smeri, da je Evropska unija ogromno kolesje birokracije, ki je kot tako oddaljeno od resničnih problemov ljudi in mu zato ne gre zaupati. Mešane občutke glede približevanja EU je bilo v času njene osamosvojitve in začetkov njenega približevanja čutiti tudi v Sloveniji, kjer je bilo javno mnenje o EU dokaj nizko. Slovenke in Slovenci so načeloma gojili pozitiven sentiment do EU, vendar pa nad njo nikdar niso bili popolnoma navdušeni. Dodatne dvome je v ljudeh zbujalo tudi dejstvo, da je takratna politika sprejela ogromno odločitev in različne regulative, ki jih vnaprej ni komunicirala z javnostjo oziroma javnosti o svojem delu ni redno obveščala. V tem prispevku zagovarjamo tezo, da je reprezentativna demokracija ni najbolj ogrožena takrat, ko politične obljube ostanejo neizpolnjene, pač pa takrat, ko političarke in politiki naredijo več, kot obljubijo, a o tem ne informirajo javnosti. V prispevku z analizo volilnih programov, javnega mnenja in medijskih objav analiziramo dva glavna problema slovenske vlade med letoma 2000 in 2004. Prvi problem zaznamo v skoraj avtomatičnem in rutinskem sprejemanju regulativ in politik EU in hkrati evidentnem umanjkanju javnih debat. Drugi problem pa vidimo predvsem v nezmožnosti vlade, da bi o svojih odločitvah dosledno informirala zainteresirano javnost in svoje odločitve približala ljudem. Čeprav analiziramo dogodke, ki so se v Sloveniji dogajali več kot 20 let nazaj pa ugotavljamo, da je raziskava izjemno relevantna tudi za trenutno dogajanje v slovenski politiki.

2Ključne besede: EU, evroskepticizem, politika, informiranje volivcev, volitve

ABSTRACT

1Euroscepticism is a common political problem in many EU member states as well as potential candidates. There is a general belief that the EU is a giant bureaucratic organization far removed from peoples’ actual needs and everyday problems and therefore not to be trusted. Such ambivalent sentiment towards the EU could also be noticed in Slovenia after it gained independence from Yugoslavia and started the EU accession process. General public opinion was rather low – people were generally sympathetic but never completely enthusiastic about the EU. What attributed to this attitude was the fact that politicians adopted several regulations without properly informing the public, therefore leaving people with little or no knowledge concerning potentially important issues. In this paper, we argue that the threat to representative democracy is not so much about politicians not keeping their promises but rather about politicians not telling their constituents what they are working on and doing even more than promised by adopting more regulations than those communicated to the public. Our analysis of election manifestos, public opinion and press releases uncovers two fundamental problems of the Slovenian government between 2000 and 2004. The first is an almost routine adoption of EU regulations without serious public debate and the second government’s consistent failure to communicate relevant matters and therefore bring them closer to the electorate. Although the analysis focuses on events that happened 20 years ago, we believe that our findings are highly relevant for the state of Slovenian politics today.

2Keywords: EU, Euroscepticism, politics, voter outreach, elections

1. Introduction

1On July 1, 2017, legendary Irish musician and activist Bob Geldof visited Slovenia as part of the Lent Festival in Maribor. This was at the time of Brexit, and Geldof was resigned and critical in his opinion both about the political situation in Europe and worldwide:

2"I am not sceptical about Europe, as I have been intimately involved with it for more than thirty years. With all European leaders. I have been to Brussels countless times. Brussels is shit. It is a colossal bureaucracy. But maybe it has to exist to reconcile all the differences in Europe. Also, nationalisms and national identities. Personally, I think the EU functions based on the French being afraid of the Germans and the Germans being afraid of themselves. Meanwhile, the English are always, at least seemingly, somewhere in the mix.”1

3In the style of a punk musician, Geldof uttered comprehensible and resounding criticism that was met with much approval. His words were almost in tune with the popular wisdom that Europe is fine but essentially colossal, distant and therefore not to be trusted. The thoughts expressed during Brexit, which for many represented yet another European crisis, were basically no different from the judgments already heard throughout Central and Eastern Europe at the time of EU accession and in the first years as new members of the EU.

4In the first EU elections after the fifth enlargement of the European Union (EU) when ten new countries joined in the so called “big bang” accession in 2004, many people shared the opinion of the Czech man when asked by a BBC reporter on the streets of Prague, whether he had voted: “I didn’t. I am against the European Union for several reasons. I don’t believe giant bureaucratic structures can help their member nations.”2

5The 2004 elections focused mainly on national issues, resulting in the lowest voter turnout in the history of EU elections and revealing a growing distance between citizens and EU institutions. As shown in Table 1, a downward trend in turnout in EU elections has been observed since 1979, with particularly low interest in the Central and Eastern European new member states. Turnout was lowest in Slovakia (16.69%) and highest in Malta (82%), with Slovenia well below the EU average (28.3%).3

| Country | 1979 | 1984 | 1989 | 1994 (1995: SE, AT, FI) | 1999 | 2004 | Trend |

| Austria | 67.7 | 49.4 | 41.8 | Downward | |||

| Belgium | 91.4 | 92.2 | 90.7 | 90.7 | 91.0 | 90.8 | Downward (mandatory voting) |

| Denmark | 47.8 | 52.2 | 47.4 | 52.9 | 50.5 | 47.8 | Downward |

| Finland | 57.6 | 31.4 | 41.1 | Upward | |||

| France | 60.7 | 56.7 | 48.8 | 52.7 | 46.8 | 43.1 | Downward |

| Germany | 65.7 | 56.8 | 62.3 | 60.0 | 45.2 | 43.0 | Downward |

| Greece | 78.6 | 77.2 | 80.1 | 80.4 | 75.3 | 62.8 | Downward (mandatory voting) |

| Ireland | 63.6 | 47.6 | 68.3 | 44.0 | 50.2 | 59.7 | Upward |

| Italy | 84.9 | 83.4 | 81.4 | 74.8 | 70.8 | 73.1 | Upward |

| Luxembourg | 88.9 | 87.0 | 96.2 | 88.5 | 87.3 | 90.0 | Upward (mandatory voting) |

| Netherlands | 58.1 | 50.6 | 47.5 | 35.6 | 30.3 | 39.1 | Upward |

| Portugal | 72.4 | 51.2 | 35.5 | 40.0 | 38.7 | Downward | |

| Spain | 68.9 | 54.7 | 59.1 | 63.0 | 45.9 | Downward | |

| Sweden | 41.6 | 38.8 | 37.2 | Downward | |||

| United Kingdom | 32.2 | 31.8 | 36.6 | 36.4 | 24.0 | 38.9 | Upward |

| Average EU-15 | 74.1 | ||||||

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Cyprus | 71.19 | ||||||

| Czech Republic | 27.9 | ||||||

| Estonia | 26.89 | ||||||

| Hungary | 38.47 | ||||||

| Latvia | 41.23 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 48.2 | ||||||

| Malta | 82.4 | ||||||

| Poland | 20.4 | ||||||

| Slovakia | 16.7 | ||||||

| Slovenia | 28.3 | ||||||

| Average | 26.4 |

6These results undoubtedly raise a whole range of issues related to the image of the EU. The "ambivalent mood" towards the Union that journalists and politicians often observe in Eastern European member states may have divisive consequences. Especially after Brexit, concerns about the future fate of the EU are becoming more frequent (although at present they have subsided somewhat due to the war in Ukraine).

7Together with our colleagues from the Institute of Contemporary History of the Czech Academy of Science (USD) in Prague, we reduced the sentiment to the "triple thesis": Admiration, Adaptation, Resistance. All three are characteristic of the field and the key question is how each of these sentiments were formed and why. The key then, is to look at contemporary history, in a specific national context, which according to the applied history approach4, can offer a convincing explanation of the issue of our time, popularly referred to as Euroscepticism.

8Euroscepticism as a political problem of mainly populist political groups and parties is a political position that involves not only criticism of the European Union as a whole, but also highlights doubts about its organizations, laws and practices. It is in opposition to European integration, certain EU policies and the path the European Union is taking.5 It is a strong feature of political landscapes across the European Union that has shaken confidence in further integration and provoked several attempts to redefine the process.6 Various surveys (e.g., Eurobarometer 2016) show that trust in the EU and its institutions declined sharply between 2004 and 2015. Although after 2016 the number of people doubting the EU started to decrease, the percentage of those doubting the institutions was still high. This can be attributed to several factors. The most important is the belief that EU integration undermines national sovereignty, that the EU is elitist, bureaucratic and wasteful, and that it lacks transparency and democratic legitimacy.7 We are aware of the weaknesses of the concept of Euroscepticism that have been repeatedly pointed out: an originally non-academic term, a negative construction, spanning from opposition to some aspect of European integration to full condemnation of the European ideal. Yet the recent situation in the EU has reawakened the academic debate, which has seen only the first attempts at historicizing and comparing Euroscepticism.8

2. General Attitude Towards the EU

1The influence of public opinion is one of the key drivers in the EU and has become increasingly important in recent decades. It is not only crucial for the discussion on European integration, but also influences national policy makers and shapes the EU institutions.9

2The general attitude towards the EU can be observed through opinion polls (through the study of public opinion in Slovenia – Slovensko javno mnenje - SJM VI), and the impact of public opinion is similar to the sentiment expressed by Geldof. We can observe that people were generally sympathetic to the EU, but never completely enthusiastic about it. They were often sceptical, partly out of concern for their own position and well-being. The results of the survey Political Culture and Democratic Values in New Democracies, conducted in 2000, are very revealing as respondents largely agreed that it would be in our country's interest to follow the path of other (Western) European countries, while at the same time they felt that Slovenia should develop more self-confidence10 before joining the European Union. In the survey conducted by Toš in 2001, respondents were asked about their feelings towards the EU and Slovenia’s accession, as well as about their level of knowledge on the most important EU issues. Tables 2 to 5 show their responses..

| Values | Categories | Frequency |

| 1 | It would benefit | 496 |

| 2 | It would not benefit | 219 |

| 9 | I do not know, no answer | 290 |

| Values | Categories | Frequency |

| 99 | No state indicated | 305 |

| 3 | Austria | 12 |

| 4 | Belgium | 1 |

| 6 | Bulgaria | 2 |

| 8 | Cyprus | 3 |

| 9 | Czech Republic | 181 |

| 11 | Estonia | 6 |

| 13 | France | 1 |

| 15 | Croatia | 134 |

| 16 | Italy | 3 |

| 20 | Latvia | 2 |

| 21 | Lithuania | 8 |

| 23 | Hungary | 143 |

| 25 | Malta | 2 |

| 29 | Norway | 1 |

| 30 | Poland | 123 |

| 32 | Romania | 22 |

| 34 | Slovakia | 33 |

| 36 | Sweden | 2 |

| Values | Categories | Frequency |

| 1 | I would regret it | 324 |

| 2 | I would not regret it | 423 |

| 3 | I do not care | 255 |

| Values | Categories | Frequency |

| 1 | Definitely agree | 149 |

| 2 | Agree slightly | 355 |

| 3 | Neither agree nor disagree | 190 |

| 4 | Disagree slightly | 187 |

| 5 | Definitely disagree | 38 |

| 9 | I do not know | 85 |

3The ambivalent attitude towards the EU is evident from Table 2, which clearly shows that almost 22% of respondents believe that Slovenia would not benefit from joining the EU. Moreover, almost 29% did not have a clear opinion on Slovenia’s EU integration, which means that more than half of the respondents were not very optimistic about integration. The high percentage of respondents who did not have a clear opinion on integration also indicates that they may be missing some important information about integration and therefore undecided about what this means. Hand in hand with these findings, the results from Table 4 also clearly show that more than half of the respondents would neither regret nor care if Slovenia’s efforts to join the EU failed. This reinforces the assumption that public opinion about Slovenia's EU accession was rather low and did not support integration.

4The problem of insufficient information being available to the public is also evident from Table 3, which shows that when asked about other EU accession candidates, approximately 33% of respondents could not name any state other than Slovenia that was on the path to EU accession. In addition, four states that were negotiating membership at the time (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Malta) were not mentioned as candidates for accession and Croatia, not a serious candidate for EU accession at the time, because it did not begin negotiations until 2003, was recognized as a state negotiating accession.

5The above-mentioned ambiguous or often negative attitude towards the EU, as well as the lack of information, can also be observed in responses about Slovenia’s development in case of non-accession to the EU. About half of the respondents believe that Slovenia could develop just as well if it were not part of the EU, and another 19% of the respondents were not able to comment directly. Only about 30% of respondents felt that Slovenia would not develop if EU integration did not take place.

6The argument about indifference is therefore not tenable either as many people are aware that funding for development of their municipalities comes from Brussels and that mayors are powerless without cohesion funds as indicated by the Opinion Poll on EU Accession conducted by Tavčar.11

| Values | Categories | Frequency |

| 1 | Definitely agree | 2597 |

| 2 | Agree slightly | 4491 |

| 3 | Neither agree nor disagree | 2437 |

| 4 | Disagree slightly | 1913 |

| 5 | Definitely disagree | 769 |

3. Methods and Approach

1Considering the above findings, we believe that additional research should be invested into a thorough investigation of the reasons for doubts about the EU and ambiguous or negative feelings about EU accession.

2In the context of the present discussion, we will use the example of Slovenia to explain attitudes towards the EU with the help of contemporary populist theories and the thesis that the gap between the elites and the general public is becoming ever more present and evident. According to Cas Mudde, there are no politics for populists because the will of the people is clear and all people are one, so there is no need for compromise. At the same time, however, all decisions must coincide with "the common will of the people" - which is not the case, because the elites decide everything. Thus, populists are in effect demanding re-politicization and the right to decide on everything, while established politics transfer more and more tasks to experts, expert groups and bureaucratic battalions and in many cases resorts to TINA (There Is No Alternative) argument. Liberal parliamentary democracy is thus, according to the populists, becoming less and less democratic.12

3The latter is particularly evident in the case of the EU, where Eurosceptic parties in the European Parliament argue precisely that decisions taken in Brussels in the past would not have met with the approval of the people if they had been better informed. The real problem, then, may be that European policy issues are not part of the domestic political spectrum and that not enough politicians talk about them and address the electorate.

4The above observation is confirmed by a brief look at the corpora available in Slovenia, which has not changed significantly (see, for example, politicians' tweets 2013-2017).13 We used Nosketch Engine14 concordancer to search the SiParl 3.0 corpus15 which we perceived to be the best option to obtain the most suitable results. When it comes to the EU, "funds" (Slovenian: sredstva) are the main topic. However, European issues encompass much more than just funds.

| Cooccurrence count | Candidate count | logDice | ||

| P | N | funds | 110 | 617 | 9.745 |

| P | N | the | 151 | 2,828 | 9.592 |

| P | N | v | 1,033 | 45,461 | 9.430 |

| P | N | of | 114 | 2,382 | 9.291 |

| P | N | o | 331 | 14,133 | 9.258 |

| P | N | zadeve | 68 | 480 | 9.099 |

3.1. Research questions

1We decided to take a closer look at the actions of the elected political elite during the last Slovenian government term before EU accession (2000-2004) - what they promised domestically and in relation to Europe, and what they achieved. In doing so, we made partial use of classical descriptive analysis, while the core of the research focused on quantitative analysis of data from the political process. We conducted a step-by- step analysis, focusing on the following research questions:

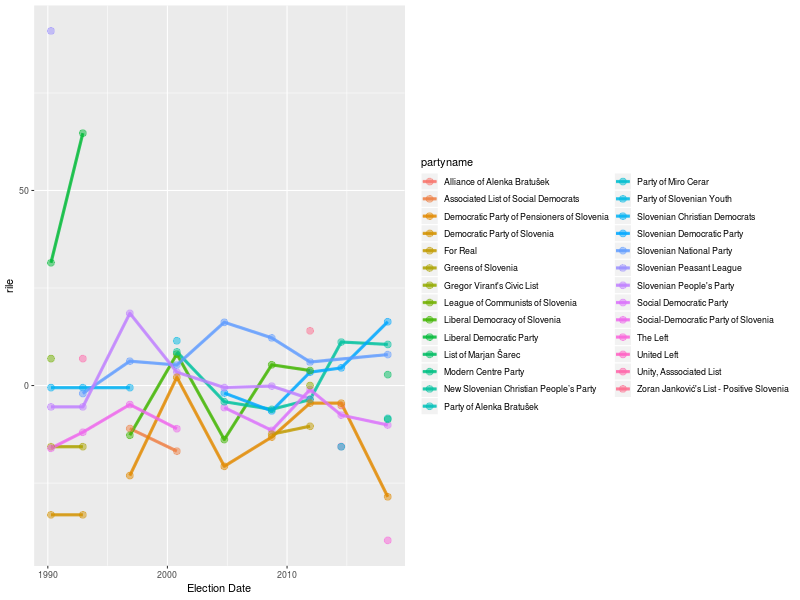

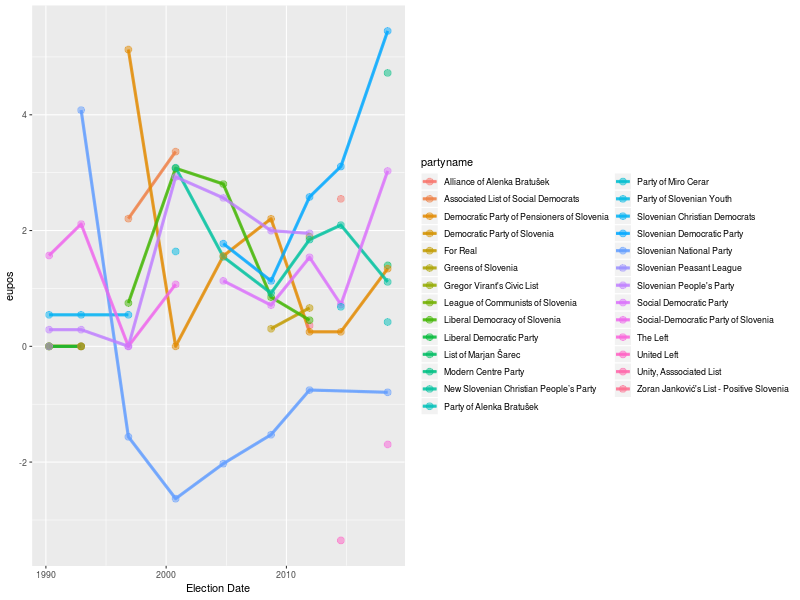

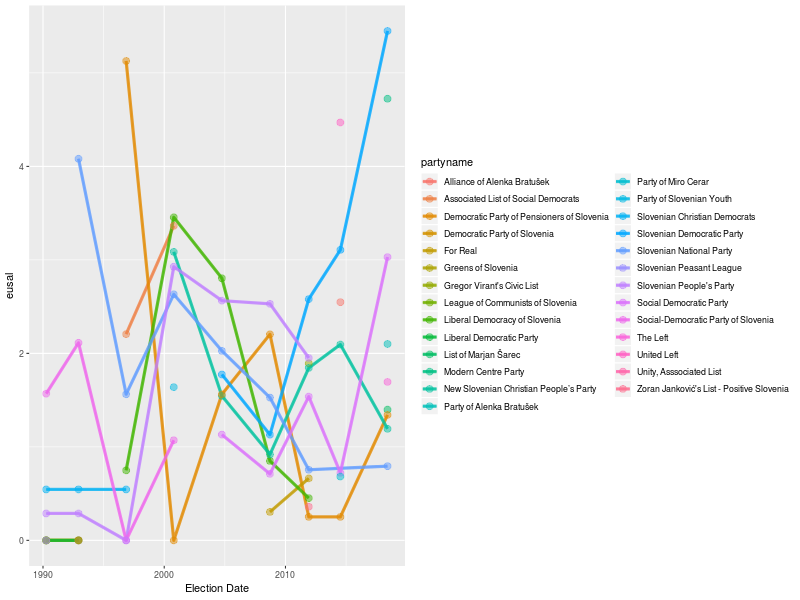

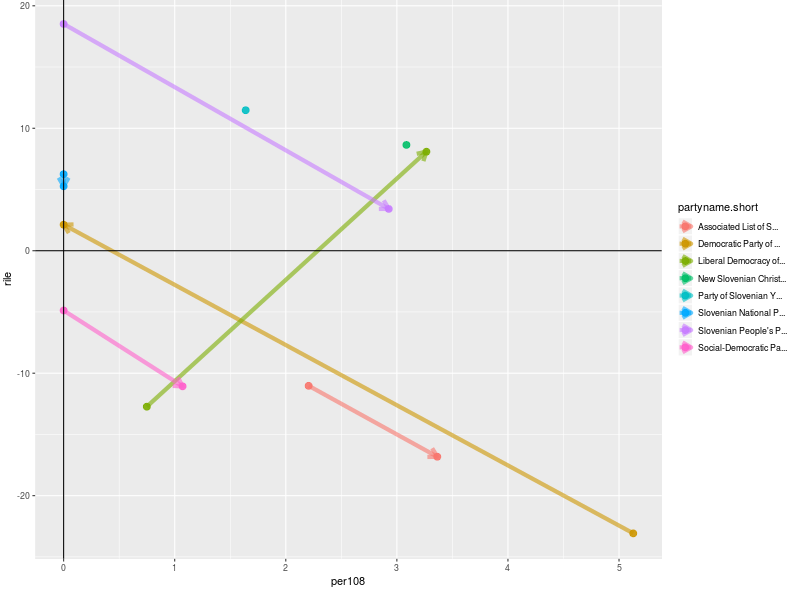

- To what extent were European topics included in the parties’ election manifestos? In this regard, we drew on The Manifesto Project16 and included the parties’ views to provide a clearer picture. We were particularly interested in the principled positions and the salience of European topics.

- How did the parties appeal to voters at the 2000 national elections (the last elections before EU accession in May 2004) and to what extent was the election campaign infused with European topics in terms of themes and content? From the methodological point of view, we relied on a classic descriptive analysis.

- What was featured in the government’s (legislative) program?

- What were the government’s week by week activities? We performed the analysis based on the agendas and a collection of press releases from all government sessions. We retrieved materials from the Government of the Republic of Slovenia archives and analyzed them quantitatively.

2In relation to the above research questions, our main thesis is that democracy is threatened by politicians delivering more than they promise. We believe that it is not so much the unfulfilled promises that are the problem (although we often perceive them as such), but rather decisions taken that were neither promised nor communicated by the government. We believe that most politics takes place behind closed doors and away from the public, which provides politicians an ideal opportunity to circumvent the "will" of the public. Therefore, we expect to see many decisions, regulations and policies that were not covered (or only partially and vaguely covered) in previous promises, but then actually implemented by the government. In other words, we claim that the number of decisions and regulations that are not part of election promises increases with the distance to the point where the parties directly address the electorate. We propose that a gap between the policies that parties directly address (or inform voters about) and the decisions that are then taken may be at the core of distrust in the EU and is responsible for the rise of populist political patterns. Therefore, we believe this thesis is worth exploring.

4. The Analysis of Election Manifestos

1Advocating ideological positions is part of election campaigns, and some parties succeed in communicating their positions much more clearly than others.17 An effective means of communicating the parties' ideological positions, views and intentions is through the publication of election manifestos. These are publications issued by political parties before elections that contain a set of policies that the party stands for and intends to implement if elected to government.18 Manifestos, therefore, can be understood as a set of intentions, motives or views of the political party, or the statement of its ideology and intentions, designed to promote new ideas that are consistent with the party's political and ideological positions. Various studies have shown that under certain conditions there is a high degree of correlation between what parties feature in their election manifestos and what governments then do.19

2We have relied on data from The Manifesto Project (Manifesto Research on Political Representation - MARPOR), whose main objective is to analyze parties' election manifestos in order to study parties' policy preferences. The Manifesto Project provides the scientific community with parties' policy positions derived from content analysis of parties' election manifestos. It covers over 1000 parties from 1945 to the present, in over 50 countries on five continents.20

3Regardless of the ideological-political positioning of each party, European issues were present in the political programs of all parties. Attitudes towards Europe have fluctuated, however have been positive among almost all parties in the period since the first multiparty elections in 1990.21 Taking a closer look at the last Slovenian elections before EU accession (in 2000), we find that positive European attitudes were even more pronounced in all major parties’ manifestos compared with the 1996 elections. Most parties emphasized the importance of membership for the country's economic and social development and security. The functioning of the EU itself and its legal framework were not examined in detail. In the following elections (2004), reference to the EU in election programs continued to have a legitimizing function. The parties used it to justify the correctness of their positions. A more visible integration of European issues with clear positions took place in the following years, but its importance remained low for a long time.22

4Even though electoral manifestos are the most "rational" instruments of electoral campaigns and are therefore considered the most appropriate material for analysis and form the substantive basis for the actions of the parties and later the government, they will not be the focus of our analysis. Rather, we are interested in the following two issues: 1) the actual share of European issues in the policy-making and decision-making process, and above all, 2) their communication impact.

5. The Context of the 2000 Election

5.1. Pre-elections events

1On Sunday, October 15, 2000, Slovenia held parliamentary elections, preceded by another campaign in which commentators and MPs assessed the second term and the established parties and public figures made appearances. Although these elections took place at the turning point of the decade, the century and the millennium, they did not in themselves represent an important milestone. Symbolically, however, they marked the beginning of a new era. The first decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall, which the "best chronicler of the 20th century," British historian Timothy Garton Ash, called the "age of freedom," came to an end, and the new "nameless decade," an elusive period of ambiguous character, began. A year earlier, the common European currency (EURO) was introduced, and NATO was enlarged to include the first three Eastern European countries, which had a special significance for the integration processes. The following year, on October 5, 2000 - just ten days before Slovenian elections - the last Yugoslav tyrant, Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević, was deposed in Belgrade. All this can be seen as historical censorship of a particular era.23

5.2. After the election

1The Slovenian Liberal Democracy (LDS), which played the leading role during transition and with one brief exception, was the strongest party in the government, won the elections for the last time. The right-wing parties suffered a heavy defeat and LDS, which also strongly supported EU accession, received an astonishing 36.21 % of the votes. The orientation of the leading political parties took a strong left-liberal turn, mainly due to non-consolidation of parties in the right-wing political spectrum and various disagreements between them. Drnovšek's LDS party therefore won, securing 34 seats in parliament. It formed a coalition with three other parties (United List of Social Democrats (ZLSD), Slovenian People’s Party (SLS) and Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia (DeSUS))24 and signed a special agreement with the Slovenian Youth Party (SMS). This secured 62 seats for all five parties in a 90-seat parliament, accounting for 2/3 of all seats and providing them with a comfortable parliamentary majority.25

2Nevertheless, the coalition formed in 2000 was, along with the 1996 coalition, one of the least homogeneous coalitions in the short period of Slovenia's independence. According to political scientists' calculations, the average Euclidean distance between the analyzed coalition partners (5) manifestos and the coalition agreement was more than 30. On the other hand, the agreement was the most extensive ever written, as it contained more than 36,000 words and unlike previous agreements, also included a separate chapter entitled Integration into the European Union.26

5.3. Campaigning and voter outreach

1The 2000 election campaign was lacked verve in many respects.27 The election posters - at that time still relevant for the promotion of parties - were monotonous, uncreative and above all, similar to each other. The Internet campaign was still in its infancy and "showed a clear lack of an online strategy." It was mainly carried out by party sympathizers, which is why it was of little significance. The traditional media - press and television - were at the forefront. In this respect, the analysis of the confrontations on TV showed that the media depended on the political "construction of problems." The issues they focused on were based on what journalists had expressed in previous months and years. They reported on what politicians said and, on that basis, shaped media discourse. In this way, the media defined the issues dictated by politicians as the most important national political issues, unconsciously adopting their language and conceptual framework as well. Breda Luthar, in her analysis of TV confrontations, argued convincingly that these issues and their language were limited to "consensus issues on government policy."28 What were the issues about? They mainly revolved around the budget gap, funding for science, relations with successor states of Yugoslavia, and of course, EU accession. The issues were clear and consensus-oriented, while the recognition of a particular point was the only source of conflict. Thus, the public was given the impression of the "inevitability of accession" in relation to the EU. This was the dominant narrative of all parties (except SNS) and the mainstream media.

2Overall, the campaign was empty of content and limited to slogans and the mindset of TINA. It was characterized by a lack of short and clear political messages addressing individual elements of EU accession. Views regarding the EU were largely reduced to the phrase: "We should integrate, but at the same time defend our own interests." The latter, however, was not reflected in media discourse. Media coverage of the negotiation process was technical, similar to legal acts from Brussels, and reduced the accession country to the role of a student busily performing tasks, sometimes praised (e.g., you are making good progress), and sometimes blamed (e.g., your structural reforms are too hesitant, you are too slow in selling state-owned enterprises, etc.).29

5.4. Government activities

1In accordance with the Rules of Procedure, the Government has prepared a program of activities for each year of its term, setting out the main tasks for each period and the deadlines. The program was prepared in accordance with the guidelines set out in the coalition agreement and, in the government's words, was "oriented towards the most important tasks related to Slovenia's accession to the European Union." Many of the legal acts to be amended for EU accession were on the agenda, but without any explanation of what exactly was being changed and why. The program only contained explanations of the legislation that was not directly related to EU accession. Once again, TINA can be observed.

2At this point, we can focus on the most interesting part of our paper - discovering what the government concentrated on in its meetings week after week. In our analysis, we rely on extensive press releases extracted from archive websites of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia.30 We focused mainly on the second part of the legislative period (formally the seventh government, 2003 - 2004), when Janez Drnovšek, elected President of the Republic of Slovenia in 2002, was replaced by Anton Rop, however the coalition remained unchanged. The government held regular meetings approximately once a week.

3The data used in the research was extracted from government websites and then converted into an XML format compliant with Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) guidelines.31 We used the SIstory XSLT profile to generate the digital edition of the collected press releases.32 CSV spreadsheets with metadata were generated for further statistical analysis. All research data and web pages created as part of the research are available in the GitLab repository.33

| Government term | Year | No. of regular sessions | Agendas | Press releases | Sessions not covered |

| 6 | 2000 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 6 | 2001 | 45 | 0 | 38 | 7 |

| 6 | 2002 | 45 | 0 | 44 | 1 |

| 7 | 2002 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 2002 | 53 | 46 | 52 | 0 |

| 7 | 2004 | 45 | 45 | 41 | 0 |

| Work programs of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia | Year | |

| 2003 | 2004 | |

| The planned adoption of legislative acts to implement EU legislation (excluding international conventions, etc., Ministry of Foreign Affairs) | 51 | 33 |

| The actual adoption: according to the data from the agendas and press releases in 2003 and 2004 | 43 | 27 |

| The planned adoption of other legislative acts | 130 | 105 |

4The planned volume of work on drafting legislation related to EU accession was considerable but fell far short of the rest of the work. However, the true picture of the volume of implementation of EU regulations emerges when we calculate the share of all items concerning EU law and the share of all other items. The results show that the government completed only a very small share of EU-related work.

| Agenda items | 2003 | 2004 | ||

| No. | Percentage | No. | Percentage | |

| EU legislation | 34 | 1.83 % | 30 | 1.48 % |

| Other | 1822 | 98.17 % | 1999 | 98.52 % |

| Total | 1856 | 2029 | ||

5The question that now arises is how these activities are reflected in the government's communication strategy. We note that press releases about the government's activities present an unusual picture. First, we note that EU-related content was always placed at the beginning of the press releases. Moreover, the average number of words in press releases dealing with EU legislation was significantly higher than the number of words in other types of press releases.

| Agenda items | 2003 | 2004 | ||||||

| Releases | Words | Releases | Words | |||||

| No. | Percentage | No. | Percentage | No. | Percentage | No. | Percentage | |

| EU legislation | 29 | 4.47% | 11,267 | 5.18% | 25 | 4.91% | 10,954 | 6.61% |

| Other | 620 | 95.53% | 206,167 | 94.82% | 484 | 95.09% | 154,883 | 93.39% |

| Total | 649 | 217,434 | 509 | 165,837 | ||||

| Item | Number of words |

| Average number of words per release regarding EU legislation | 411.5 |

| Average number of words per other releases | 327.0 |

6. Discussion

1After gaining independence from Yugoslavia, Slovenia became a parliamentary democratic republic where the power belongs to the people. However, the basis for a successful democracy is that the general public is consistently transparently informed about the actions of the government.34 This means that governments must openly discuss their plans, activities and procedures and make this information available to the public, especially when it comes to discussing important policy decisions or deciding on significant political issues (e.g., accession to the EU). Governing, therefore, necessarily involves a constant exchange of information and communication about policies, ideas and decisions between the governing and the governed35 that ensures the public is informed about the government’s activities in a transparent manner. The public needs to be suitably informed not only about who they elect as head of government36 (pre-election information), but also about what politicians do and how they keep their campaign promises. However, government communicators often fail to inform the public about key policy decisions and what politicians are actually doing. We see this as a serious threat to democracy, as the public is not informed about the content of government activities.

2Our analysis shows two fundamental problems of the Slovenian government in the period from 2000 to 2004. The first problem is the almost automatic and routine adoption of EU regulations without serious public debate. This observation can be deduced from the above data, which show that the government completed only a limited amount of EU-related tasks and that regulations were indeed adopted routinely. We can see, for example, that the program does not contain any meaningful communication besides the frequent There Is No Alternative (TINA) argumentation. This clearly shows the attitude of Slovenian political parties towards the EU; Slovenia's accession to the EU is seen as inevitable and politicians would like to show that they are prepared to do whatever is necessary for integration. It can be assumed that the government's communication officers acted in this way deliberately and after careful consideration, as they wanted to create the impression that Slovenia is acting as a "good student" on the road to EU integration.

3The second problem is that the public was not informed about the actual work of the Slovenian government. The government failed to communicate relevant matters in a timely manner, to address any negative aspects and by doing so bring them closer to their constituents. The public was only informed after the government had adopted the regulations. As a result, public debate failed to materialize, and the EU remained a large bureaucratic organization that was at the forefront of the government's activities, but without content for the public. The main impression was that many regulations regarding the EU were passed without the public being informed about what was actually decided. Such a lack of communication and information creates a breeding ground for the development of populist policies, as "the people" (who are the main point of reference for populists) will eventually no longer tolerate them. And the general characteristics of the 2000-2004 legislative period strongly support this thesis and findings.

4It should also be noted that the main issues discussed in public were not related to the process of European integration, but to areas that were the focus of ideological-political disputes. For example, one of the most notorious parliamentary debates of the third term was concerning medically assisted infertility treatment. After the introduction of the Act on Infertility Treatment and Fertilization Procedures with Biomedical Assistance,37 ideological and moral differences became evident in the Slovenian parliament, leading to several political statements that had mostly negative connotations in public. Moreover, the issue of "national interest" in the economy was one of the main reasons for several confrontations between Prime Minister Janez Drnovšek and opposition leader Janez Janša. The latter claimed that the government neglects the "national interest" and is ineffective when it comes to the sale of Slovenian companies to foreign investors. Such debates raised several questions, such as "What does national interest mean anyway?" and "Does the term presuppose a majority domestic shareholding in the capital?" As a result, parliamentary debates were often extremely discordant, cynical and combative, which was particularly evident on the issue of the "erased," a topic that at its core, reveals the dark side of Slovenian transition. After gaining independence in 1991, citizens of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia were automatically granted Slovenian citizenship, while those who came from other republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) had the opportunity to apply for citizenship within a period of six months. However, those who for whatever reason, did not apply for citizenship in time, or if their application was rejected for whatever reason, were removed from the population register by the Slovenian state, depriving them of all their constitutional rights.38

5The split between the coalition and the opposition continued to intensify even after Janez Drnovšek resigned from the post of Prime Minister and was appointed President of the Republic. However, one of the few issues that united almost all deputies was their stance on EU accession and joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). As a result, the National Assembly had no difficulty passing the necessary harmonization laws and amending the constitution in February 2003. According to the two presidents of the Assembly, Borut Pahor and Feri Horvat, "much was achieved in terms of the scope of the work, and it was also important in terms of its content." This is certainly true, but the problem that most of the provisions were not disclosed to the public remained at the forefront.

7. Conclusion

1In public debates about politics, it is often argued that democracy is severely compromised primarily because politicians often fail to keep their (pre-election) promises, that what is said or promised is rarely addressed in parliament and that politicians do little and live off the people. Such arguments suggest that many citizens are fundamentally misinformed about the range of political issues and political figures, leading to misconceptions about the work of politicians.39 We argue that the real problem and threat to representative democracy is not the incompetence of politicians, nor the work they do not perform but rather the work they do but about which the public is not informed. We show that in addition to what they promise, politicians are involved in many other activities that the public are not aware of. They pass countless resolutions and regulations that are not discussed in real terms during the election campaign but are wrapped up in a few uninformative phrases that often go unnoticed or unintentionally ignored by the public. We see a crucial problem in the fact that politicians are often very busy informing the public about regulations and decisions when they have already been passed and they do not discuss them beforehand.

2After this analysis, we see that our initial thesis that democracy is threatened by the fact that politicians deliver more than they promise should be modified by the following observation: European issues were omnipresent in Slovenian politics and imbued with positive sentiments, but they lacked substance in communications with voters. By passing European laws, the government tried to win over voters. It communicated the regulations more frequently than usual and assigned them a central role, but only after they had been passed. This was because, despite the voters' feelings and thoughts, as responsible politicians they had no other alternative to the EU. It must be noted, however, that the mentality of "no matter what the voters think" can sometimes be dangerous, as recent social media attacks on the German foreign minister clearly show.40

3Our initial thesis, therefore, is that the adopted regulations are the sum of the difference between election promises and unfulfilled election promises on the one hand and regulations that are not part of the election promises on the other. In other words, the adopted regulations consist of the fulfilled campaign promises and the regulations that were not part of the campaign promises, the latter being a variable that is more important than campaign promises and fulfilled campaign promises. When the thesis is corrected, it remains essentially the same, with the only difference being the definition of regulations that are not part of pre-election promises. In the corrected thesis, these regulations are defined as a variable that receives much attention from government communicators but is often not communicated to the public.

| Initial thesis | Corrected thesis |

1S = (o – x) + N; N > o; N > o – x 2S= adopted regulations 3o = pre-election promises 4x = unfulfilled pre-election promises 5N = regulations not part of the pre-election promise | 1S = (o – x) + N 2S= adopted regulations 3o = pre-election promises 4x = unfulfilled pre-election promises 5N = receives high attention from government communicators. |

4Our analysis therefore focuses on regulations that are not part of the electoral promises but are nevertheless part of the politicians' program and their work. According to our initial conjectures, such schemes and deliberate miscommunication pose a serious threat to representative democracy, as they imply that politicians are working on issues and actions that were not included in their manifestos and therefore constituents are simply not aware. Moreover, we show that the threat to democracy is exacerbated by the fact that the public is informed only after regulations have already been passed and important policy decisions have already been made. This creates a sense among voters that their opinions do not matter and that their voices are heard and "made "useful" only when politicians need them to get elected.

5Although our analysis refers to the period of Slovenia's EU integration (one of the most important periods in Slovenian political history) almost 20 years ago, we believe that our results are even more meaningful today. Politics have indeed taken an interesting turn, where mainstream media coverage is often replaced or intertwined by posts from politicians on social media, which especially before elections, are filled with promises, ideas and plans, if elected. Therefore, it would be interesting to conduct similar research today, not focusing on “traditional” media, but analyzing the activities of the most prominent Slovenian coalition and opposition politicians in social media. We believe that such a study would provide a useful insight into the development of politics and how much this differs from politics during the period of Slovenian independence and EU accession.

Sources and Literature

- Alibert, Juliette. "Euroscepticism: the root causes and how to address them." (2015).

- Alvarez, Robert. "Attitudes toward the European Union: The role of social class, social stratification, and political orientation." International Journal of Sociology 32, No. 1 (2002): 58–76.

- Am Orde, Sabine. “Desinformation von der Stange.” Taz, September 2, 2022. https://taz.de/Social-Media-Kampagne-gegen-Baerbock/!5878877/.

- Becoming a Republic. “From elections to elections...” accessed May 11, 2023. http://www.slovenia25.si/i-feel-25/timeline/becoming-a-republic/from-elections-to-elections/index.html.

- Bizjak, Andrej. “Vpliv volilnih sistemov na sestavo in delovanje parlamentov s poudarkom na delovanju Slovenskega parlamenta.” Diplomsko delo, Univerza v Ljubljani, 2003.

- Kastelic, Brane. “Evropa v 2004: ne samo leto širitve.” BBC Slovene.com, December 30, 2004. https://www.bbc.co.uk/slovene/news/story/2004/12/041230_europe2004.shtml.

- Cobb, Michael D., Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler. "Beliefs don't always persevere: How political figures are punished when positive information about them is discredited." Political Psychology 34, No. 3 (2013): 307–26.

- Euractiv. “European Parliament Elections 2004: Results,” June 30, 2004. Accessed 8. 5. 2023. https://www.euractiv.com/section/elections/linksdossier/european-parliament-elections-2004-results.

- Euroscepticisms, The Historical Roots of a Political Challenge. Edited by Mark Gilbert, and Daniele Pasquinucci. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publisher, 2020.

- Fairbanks, Jenille, Kenneth D. Plowman, and Brad L. Rawlins. "Transparency in government communication." Journal of Public Affairs: An International Journal 7, No. 1 (2007): 23–37.

- Gulmez, Seck. "EU-scepticism vs. euroscepticism. re-assessing the party positions in the accession countries towards EU membership." EU Enlargement. Current Challenges and Strategic Choices Europe plurielle–Multiple Europes 50 (2013).

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. "Sources of euroscepticism." Acta Politica 42 (2007): 119–27.

- Kaal, Harm, and Jelle van Lottum. "Applied History: Past, Present, and Future." Journal of Applied History 3, No. 1-2 (2021): 135–54.

- Kaj je izbris? | Izbrisani. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.mirovni-institut.si/izbrisani/opis-izbrisa/index.html.

- Kocjan, Aleš, and Uroš Esih. “Bob Geldof na Lentu: Ne razumete se, ker ste zajeb*** idioti.” Večer, June 29, 2017. https://vecer.com/prosti-cas/bob-geldof-na-lentu-ne-razumete-se-ker-ste-zajeb-idioti-6275625.

- Lipicer Kustec, Simona, Samo Kropivnik, Tomaž Deželan, and Alem Maksuti. Volilni programi in stališča. Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2011.

- Lo, James, Proksch , Sven-Oliver Proksch, and Jonathan B. Slapin. "Ideological clarity in multiparty competition: A new measure and test using elections manifestos." British Journal of Political Science 46, No. 3 (2016): 591–610.

- Luthar, Breda. "Oslepljeni in ohromljeni od nevtralnosti." In Mit o zmagi levice: Mediji in politika med volitvami 2000 v Sloveniji, 201–12. Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, 2001.

- Luthar, Breda. Mit o zmagi levice: Mediji in politika med volitvami 2000 v Sloveniji (Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, 2001).

- Manifesto Project Database. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/information/documents/information.

- Mašanovič, Božo. “Do vstopa v EU še veliko dela.” Slovenski almanah (2001): 23, 24.

- Mudde, Cas. "The populist zeitgeist." Government and Opposition 39, No. 4 (2004): 541–63.

- Pančur, Andrej. “Sustainability of Digital Editions: Static Websites of the History of Slovenia – SIstory Portal.” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 59, No. 1 (2019): 157–78. Accessed May 18, 2023, https://ojs.inz.si/pnz/article/view/348.

- Pančur, Andrej. Seje vlade Republike Slovenije, distributed by DIHUR GitLab. Accessed May 18, 2023, https://dihur.si/parl/seje_vlade.

- Sanders, Karen, and María José Canel. Government communication: Cases and challenges. London: Bloomsbury academic, 2013.

- Tavčar, Rudi. "Mnenjska raziskava o priključitvi k EU.” University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, (2002). https://doi.org/10.17898/ADP_EUACC00_V1.

- Text Encoding Initiative, P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange, Version 4.6.0, April 4, 2023. Accessed May 18, 2023, https://tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/index.html.

- Thomson, Robert. "Parties’ Elections Manifestos and Public Policies." (2020)

- Toš, Niko. "Slovensko javno mnenje 2001/1: Stališča Slovencev o pridruževanju Evropski Uniji in Mednarodna raziskava o delovnih aktivnostih." Ljubljana: Univerza v Ljubljani, Arhiv družboslovnih podatkov. ADP-IDNo: SJM011. https://www.adp.fdv.uni-lj.si/opisi/sjm011 (2001).

- UK Parliament. “Elections manifestos.” Accessed May 10, 2023. https://www.parliament.uk/site-information/glossary/manifesto/

- Vlada Republike Slovenije, Sporočila za javnost. Accessed May 18, 2023, http://vlada.arhiv-spletisc.gov.si/delo_vlade/sporocila_za_javnost/index.html.

- Volkens, Andrea, Tobias Burst, Werner Krause, Pola Lehmann, Theres Matthieß, Sven Regel, Bernhard Weßbels, and Lisa Zenther. The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2021a. (2021). Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2021a.

- Zajc, Drago, Samo Kropivnik, and Kustec Lipicer, Simona. Od volilnih programov do koalicijskih pogodb (Ljubljana: FDV, 2012), 90–91, 98–99, 114.

- Zakon o zdravljenju neplodnosti in postopkih oploditve z biomedicinsko pomočjo (ZZNPOB). Act - September 7, 2000. Accessed May 11, 2023, http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO2518#.

Jure Gašparič

Andrej Pančur

Jure Skubic

NAŠA EVROPSKA POLITIKA ZA ZAPRTIMI VRATI: VZROKI EVROSKEPTIZICMA V SLOVENIJI

POVZETEK

1Avtorji v prispevku naslavljajo perečo tematiko evroskeptizima in analizirajo vzroke, ki so pripomogli k dvomom glede pridruževanja Slovenije Evropski uniji. V času po osamosvojitvi leta 1991 je Slovenija postala demokratična republika v kateri ima oblast ljudstvo, njegovo voljo pa izpolnjujejo demokratično izvoljeni političarke in politiki. V svojih volilnih programih se političarke in politiki zapišejo svoje aktivnosti in obljube v primeru izvolitve ter programe tako uporabljajo za nagovarjanje volivk in volivcev. Pogosto pa se zgodi, da po eni strain volilne obljube ostanejo neizpolnjene, po drugi strani pa političarke in politiki delajo veliko več, vendar o tem ne obveščajo javnosti. Avtorji v prispevku postavijo tezo, da glavne grožnje reprezentativni demokraciji ne predstavljajo toliko neizpolnjene politične obljube, pač pa dejstvo, da so političarke in politiki bolj aktivni in delajo veliko več, kot je komunicirano z javnostjo. To se je jasno pokazalo v analizi medijskih objav, ki so se v veliki večini primerov bolj kot na objave o delu povezanem z evropsko integracijo navezovale na druge tematike, s katerimi se je ukvarjala takratna politika.

2Avtorji v svoji raziskavi izpostavijo dva glavna problema slovenske politike med letoma 2000 in 2004. Prvi problem se nanaša na skoraj rutinsko in avtomatično sprejemanje EU regulativ in zakonodaje, o katerih javnost skorajda ni bila obveščena. Tako se je v javnosti ustvaril občutek, da vlada integraciji Slovenije v EU ni povzročala veliko pozornosti, pa čeprav so se veliko ukvarjali s tovrstno tematiko in integracijo tudi uspešno zaključili. Drugi problem, ki ga izpostavijo avtorji, se kaže v dejstvu, da vladne komunikacijske službe javnosti niso jasno informirale o pomembnih tematikah, jih niso problematizirale in jih prav tako niso približale ljudem. Velikokrat je do informiranja javnosti prišlo šele takrat, ko so bile odločitve že sprejete.

3V analizi so avtorji jasno opozorijo na problem neinformiranja javnosti glede sprejemanja najpomemnejših političnih odločitev in izspotavijo dejstvo, da je veliko političnih odločitev sprejetih brez vednosti javnosti. Avtorji to vidijo kot izjemno problematično politično prakso, ki predstavlja nevarnost za demokratično družbo, hkrati pa v javnosti ustvarja občutek, da se politiki ne ukvarjajo z najpomembnejšimi problem v državi. Avtorji ugotavljajotudi, da bi bila dotična analiza, čeprav se nanaša na dogodke, ki so se dogajali več kot 20 let nazaj, relevantna tudi danes, predvsem z vsepojavnostjo družbenih omrežij, ki so povzročili, da se je dobršen del politčne komunikacije preselil tja.

* The research was carried out in the framework of research programs P6-0281 Politična zgodovina [Political History], and P6-0436 Digitalna humanistika [Digital Humanities], which are co-financed by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) from the state budget, and RSF.

** PhD, Research Counsellor, Institute of Contemporary History, Privoz 11, SI-1000 Ljubljana; jure.gasparic@inz.si

*** PhD, Research Fellow, Institute of Contemporary History, Privoz 11, SI-1000 Ljubljana; andrej.pancur@inz.si

**** Assistant and Researcher, Institute of Contemporary History, Privoz 11, SI-1000 Ljubljana; jure.skubic@inz.si

1. Aleš Kocjan and Uroš Esih, “Bob Geldof na Lentu: Ne razumete se, ker ste zajeb*** idioti,” Večer, June 29, 2017, accessed 8. 5. 2023, https://vecer.com/prosti-cas/bob-geldof-na-lentu-ne-razumete-se-ker-ste-zajeb-idioti-6275625.

2. Brane Kastelic, “Evropa v 2004: ne samo leto širitve,” BBC Slovene.com, December 30, 2004, accessed 8. 5. 2023, https://www.bbc.co.uk/slovene/news/story/2004/12/041230_europe2004.shtml.

3. “European Parliament Elections 2004: results,” Euractiv, June 30, 2004, accessed 8. 5. 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/elections/linksdossier/european-parliament-elections-2004-results/.

4. Harm Kaal and Jelle van Lottum, "Applied History: Past, Present, and Future," Journal of Applied History 3, No. 1-2 (2021): 135–54.

5. Seck Gulmez, "EU-scepticism vs. euroscepticism. re-assessing the party positions in the accession countries towards EU membership," EU Enlargement. Current Challenges and Strategic Choices Europe plurielle–Multiple Europes 50 (2013).

6. Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks, "Sources of Euroscepticism," Acta Politica 42 (2007): 119–27.

7. Juliette Alibert, "Euroscepticism: the root causes and how to address them" (2015).

8. Euroscepticisms, The Historical Roots of a Political Challenges, eds. Mark Gilbert and Daniele Pasquinucci (Leiden and Boston: Brill Publisher, 2020).

9. Robert Alvarez, "Attitudes toward the European Union: The role of social class, social stratification, and political orientation," International Journal of Sociology 32, No. 1 (2002): 58–76.

10. Niko Toš, "Slovensko javno mnenje 2001/1: Stališča Slovencev o pridruževanju Evropski Uniji in Mednarodna raziskava o delovnih aktivnostih." Ljubljana: Univerza v Ljubljani, Arhiv družboslovnih podatkov. ADP-IDNo: SJM011, https://www.adp.fdv.uni-lj.si/opisi/sjm011 (2001).

11. Rudi Tavčar, “Mnenjska raziskava o priključitvi k EU,” University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana (2002), https://doi.org/10.17898/ADP_EUACC00_V1.

12. Cas Mudde, "The populist zeitgeist," Government and Opposition 39, No. 4 (2004): 541-63.

13. NoSketch Engine, https://www.clarin.si/ske/#dashboard?corpname=janes_twepo .

14. Available at: https://www.clarin.si/noske/

15. Available at: https://www.clarin.si/noske/run.cgi/corp_info?corpname=siparl30&struct_attr_stats=1

16. Manifesto Project Database, accessed May 10, 2023, https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu.

17. James Lo, Sven-Oliver Proksch, and Jonathan B. Slapin, "Ideological clarity in multiparty competition: A new measure and test using elections manifestos," British Journal of Political Science 46, No. 3 (2016): 591–610.

18. UK Parliament, “Elections manifestos,” accessed May 10, 2023, https://www.parliament.uk/site-information/glossary/manifesto/.

19. Robert Thomson, "Parties’ Elections Manifestos and Public Policies" (2020).

20. Manifesto Project Database, accessed May 10, 2023, https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/information/documents/information.

21. Andrea Volkens et al., “The Manifesto Data Collection,” Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2021a. (2021). Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2021a.

22. Simona Kustec Lipicer, Samo Kropivnik, Tomaž Deželan and Alem Maksuti. Volilni programi in stališča (Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2011).

23. Becoming a Republic. “From elections to elections...,” accessed May 11, 2023. http://www.slovenia25.si/i-feel-25/timeline/becoming-a-republic/from-elections-to-elections/index.html.

24. Ibidem.

25. Andrej Bizjak, “Vpliv volilnih sistemov na sestavo in delovanje parlamentov s poudarkom na delovanju Slovenskega parlamenta” (diplomsko delo, Univerza v Ljubljani, 2003).

26. Drago Zajc, Samo Kropivnik and Simona Kustec Lipicer, Od volilnih programov do koalicijskih pogodb (Ljubljana: FDV, 2012), 90–91, 98–99, 114.

27. Breda Luthar, Mit o zmagi levice: Mediji in politika med volitvami 2000 v Sloveniji (Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, 2001).

28. Breda Luthar, "Oslepljeni in ohromljeni od nevtralnosti," in Mit o zmagi levice, 201-12.

29. Božo Mašanovič, “Do vstopa v EU še veliko dela,” Slovenski almanah (2001): 23–24.

30. Vlada Republike Slovenije, Sporočila za javnost, accessed May 18, 2023, http://vlada.arhiv-spletisc.gov.si/delo_vlade/sporocila_za_javnost/index.html.

31. Text Encoding Initiative, P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange, Version 4.6.0, April 4, 2023, accessed May 18, 2023, https://tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/index.html.

32. Andrej Pančur, “Sustainability of Digital Editions: Static Websites of the History of Slovenia – SIstory Portal,” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 59, No. 1 (2019): 157-78, accessed May 18, 2023, https://ojs.inz.si/pnz/article/view/348.

33. Andrej Pančur, Seje vlade Republike Slovenije, distributed by DIHUR GitLab, accessed May 18, 2023, https://dihur.si/parl/seje_vlade.

34. Jenille Fairbanks, Kenneth D. Plowman and Brad L. Rawlins, "Transparency in government communication," Journal of Public Affairs: An International Journal 7, No. 1 (2007): 23–37.

35. Karen Sanders and María José Canel, Government communication: Cases and challenges (London: Bloomsbury academic, 2013).

36. Fairbanks, Plowman, and Rawlins, "Transparency in government communication," 23–37.

37. Pravno-informacijski sistem Republike Slovenije, “Zakon o zdravljenju neplodnosti in postopkih oploditve z biomedicinsko pomočjo (ZZNPOB)”, Act September 7, 2000, accessed May 15, 2023, http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO2518#.

38. Izbrisani: informacije in dokumenti, “Kaj je izbris?,” accessed May 15, 2023, https://www.mirovni-institut.si/izbrisani/opis-izbrisa/index.html.

39. Michael D. Cobb, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler, "Beliefs don't always persevere: How political figures are punished when positive information about them is discredited," Political Psychology 34, No. 3 (2013): 307-26.

40. German foreign minister Annalena Baerbock, without regard to the opinion of the German public and against the opinion of her constituents, reiterated the support she had already pledged to Ukraine during Russia's aggression against Ukraine. This pledge was followed by a fierce smear campaign in which many voters expressed their distrust and dissatisfaction with the foreign minister primarily because she "does not represent the interests of German voters, but those of Ukraine." However, the video of her statement was manipulated, and this manipulation was fueled by pro-Russian disinformation and cyber activism, as her statement was taken out of context in such a way that it falsely reinforced anti-German sentiments. (Sabine am Orde, “Desinformation von der Stange,” Taz, September 2, 2022, https://taz.de/Social-Media-Kampagne-gegen-Baerbock/!5878877/.)