Urban Street Architecture, the K67 KIOSK: a Single Solution for All Problems

IZVLEČEK

URBANA ULIČNA ARHITEKTURA, KIOSK K67: ENA REŠITEV ZA VSE TEŽAVE

1Avtorica v prispevku predstavi kompleksno pot razvoja ter evolucijo univerzalno in modularno zasnovanega kioska K67 − znamenitega rdečega kioska slovenskega arhitekta in industrijskega oblikovalca Saše Janeza Mächtiga od njegove zasnove v drugi polovici 60. let, nadgradnje in specializacije glede na funkcijo v 70. letih, do današnjega posodabljanja v interaktivni samooskrbni večnamenski kiosk za enaindvajseto stoletje K21. Kiosk K67 − izdelek urbane ulične industrijsko oblikovane arhitekture je nastal pod vplivom tedaj aktualnih arhitekturnih gibanj zaradi naraščajočih potreb mesta in razvoja urbanih storitvenih dejavnosti. Mini cestna arhitektura, v katero so umeščali prodajalne časopisov, tobaka, hrane, manjše delavnice, cvetličarne, blagajne za plačilo parkirnine in nakup vstopnic, informacijske pisarne, turistične poslovalnice, vratarnice ipd., je poleg splošne urbane kulture nekdanjega jugoslovanskega prostora postala tudi del urbanega prostora bivših vzhodno evropskih socialističnih držav in kultni izdelek ter del kolektivne zavesti in spomina.

2Ključne besede: kiosk, modularna arhitektura, industrijski design, Slovenija, Jugoslavija

ABSTRACT

1In the following contribution, the author presents the complex development and evolution of the universally and modularly designed K67 Kiosk – the famous red booth by the Slovenian architect and industrial designer Saša Janez Mächtig – from its conception in the second half of the 1960s through its upgrades and specialisation in the 1970s to today’s modernisation as an interactive self-service multipurpose kiosk for the twenty-first century, the K21. The K67 Kiosk – a product of urban street industrial design architecture – was created under the influence of the architectural trends at the time and due to the growing needs of the city and the development of urban service activities. The miniature street architecture, which used to house newspaper, tobacco, and food shops, small workshops, flower shops, parking and ticket booths, information and tourist offices, gatehouses, etc., became a part of the general urban culture of the former Yugoslav territory, the urban space of former Eastern European socialist countries, the collective consciousness and memory, as well as a cult product.

2Keywords: kiosk, modular architecture, industrial design, Slovenia, former Yugoslavia

1. Introduction

1The purpose of the present contribution is to use the example of an industrial design product, the K67 Kiosk, to shed light on the development and role of urban street architecture, designed in the former Yugoslavia in the 1960s. That was the time when Yugoslavia was experiencing dynamic development in all areas of social life after the abandoning the centrally planned socialist economy of the Soviet type, the introduction of self-management in the 1950s, and the transition to an economy with some market elements. To better understand the creation of the K67 Kiosk, designed under the influence of the contemporaneous architectural trends due to the growing needs of the cities and the development of urban service activities, it is necessary to begin by briefly outlining the characteristics of the post-war Yugoslav regime, the role of architecture, and the emergence and rise of Slovenian industrial design. The significance of the K67 Kiosk – an example of mini-architecture suitable for any space with the possibility of combining several smaller units into a larger one – is mainly reflected in the fact that as micro-architecture fascinated with the new emerging materials, it established the social, productive-technological, and commercial aspects of the development of street furniture. The K67 Kiosk became a part of the general urban culture, especially in former Yugoslavia and Eastern European socialist countries.

2. From Capitalism to Socialism and the Role of Architecture

1With the introduction of a new political and socio-economic system – socialism – in Yugoslavia after World War II, the processes of communist modernisation, industrialisation, and urbanisation were set in motion in an effort to implement profound social changes. Yugoslavia and Slovenia as its part underwent a major social, economic, and cultural transformation. The Slovenian society gradually transformed from peasant to industrial. After assuming power and introducing socialism, the new communist rulers nationalised all of the important enterprises and imposed new economic conditions as well as a new development policy in accordance with the Soviet model. Initially, this new development policy assumed an accelerated consolidation of the so called material base, while as of the mid-1950s, it also focused on the swift increase of the living standard. The material foundations were to be strengthened by focusing on the construction of basic heavy industry and electrification, while the enhancement of the living standard was to be ensured by extending economic development to all areas of the economy.

2In the early 1950s, Yugoslavia started to build a sort of a third model of socio-economic development – one that was neither capitalist nor centrally planned. It replaced the socialist centrally planned economic and social system with self-management. Thus, it established socialist social ownership, distinct from private and collective property under capitalism as well as from the Soviet-style state socialist ownership. Social ownership as the foundation for self-management meant that companies were owned neither by the state nor by private individuals but rather by all workers. With the introduction of self-management, the decentralisation and relaxation of economic rules in all of the more important areas of economic life took place.

3Although the economic policy after 1958 started to shift towards more balanced investments and the development of activities that affected the living standard, Slovenia’s economic progress during the socialist period was dominated by industrialisation. The latter penetrated Slovenia earlier than the other Yugoslav territories, but still with a significant lag compared to Western and Northern Europe. In the first post-war years, Slovenia was only partially industrialised, but over the next four decades, it became an industrially developed.1 As employment and personal incomes increased markedly, so did the purchasing power or the living standard of the population. The needs of the consumers increased, and they became more demanding.

4During the socialist period, architecture was seen as an important task of the authorities, aimed at improving the people’s living conditions as well as at increasing the general living standard. Architects and architecture as a profession had a moral duty to contribute to an objective general improvement of the quality of living. This marked a break with the tradition of pre-war architecture, which had focused on design expressiveness. In the new system, architects were assigned the role of illuminators. “Increasing the awareness of our masses and enriching their general culture with basic architectural and urban planning knowledge is one of the tasks of urban planners and architects,” wrote the editorial board of the Arhitekt magazine at the beginning of its publication based on the summarised conclusions of the 1st Consultation of Architects of Yugoslavia in Dubrovnik in 1950.2 In addition to their traditional tasks, architects were assigned the duty of educating the general public. Both the Yugoslav and the Slovenian Architects’ Society actively participated in this process by organising professional seminars, exhibitions at home and abroad, publishing the specialised magazine Arhitekt, and with many other activities. In this regard, the role of the architect and Professor Edvard Ravnikar from the Faculty of Architecture and Civil and Geodetic Engineering (FAGG) in Ljubljana should be highlighted.3

5In the context of the demands for rational and economical production, the focus was on profoundly social and cultural architecture – one that would be “an expression of modern times in the best possible sense”.4 Like all over Europe, a modern design trend asserted itself, such as had been followed in Scandinavia for a long time. Since the first major Slovenian furniture exhibition, titled Stanovanje za naše razmere (Apartment for Our Circumstances), which took place in Ljubljana in 1956, this trend was also adhered to by the Slovenian architects. Slovenian architecture did not follow the development of architecture in the other socialist countries, as the younger-generation architects, led by Edvard Ravnikar, were able to take advantage of the Yugoslav dispute with the Soviet Union in 1948 and sought contacts with the contemporary global architectural trends. Ravnikar’s theses on the importance of architectural theory and the need to broaden the horizons led indirectly to the establishment of contacts with the Swiss and Scandinavian architecture and their ideas on social construction in particular.5 Functionalist principles that followed the example of the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier were applied. The architectural concepts of space were meant to reflect the socialist relations, which were supposed to be evident from the non-elitism of the new concepts, and result in the improvement of everyone’s quality of life. The new urban designs were to generate a sense of belonging to the community. The architectural profession presented advanced architectural designs to a broad circle of people, emphasising economy and new, higher living standards.

3. The Emergence and Development of Slovenian Industrial Design

1The professionalisation of Slovenian industrial design in the former Yugoslavia began after World War II. Otherwise, its origins date back to 1919, to the time when the University of Ljubljana was founded. After its establishment in 1920, the Department of Architecture started operating as well.6 The emergence of industrial design in Yugoslavia was undoubtedly linked to industrial development, especially to the enormous needs of the post-war wood processing industry, which gradually focused on the production of well-designed and affordable mass-produced furniture. The post-war reconstruction of demolished apartments, the intensive construction of new residential developments and terraced houses in cities and factory settlements in industrial centres, and the construction of entirely new urban settlements called for vast quantities of furniture. In the context of post-war reconstruction and construction, the furniture industry, woodworking technologies, and industrial design developed rapidly.7

2In the context of the housing crisis, the new concept of housing construction sought to rationalise the construction of minimum housing with the maximum utility of the differentiated housing areas. At the same time, the apartments needed to be well thought out, efficiently designed, and furnished in a suitable and practical way.8 This resulted in great demand for designers and architects. In the 1960s and 1970s, design in Slovenia was mainly in the domain of architects, as the higher education design studies at the Academy of Fine Arts were not established until 1984. However, the importance of small industrial objects was pointed out by the aforementioned architect and Professor Edvard Ravnikar already at the end of 1948, as he introduced weekly discussions with the students at the Department of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana. From the very beginning, when he became a professor at the Department of Architecture after the end of the war in 1945, Ravnikar, together with other architects, kept underlining the fact that Slovenia, which otherwise had various arts and crafts departments, did not yet have a school of design, either at the university or secondary school level. His efforts yielded results as early as in 1946: the Secondary School of Design and Photography (SŠOF) opened its doors in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia.9

3The magazine for architecture, urban planning, and applied arts, titled Arhitekt (1951–1963) and published by the Slovenian Architects’ Society, also endeavoured to assert design as a profession. The rise of design as a discipline began with the introduction of design and development departments in industrial companies in the 1950s. The 1950s can be described as a pioneering period in design. The first development department and design bureau was established in 1952 by the architect, designer, and inventor Niko Kralj after he joined one of the most important companies in the furniture industry: the Stol factory in Duplica near Kamnik. He persuaded the factory management to abandon licensed products or redesigns in favour of its own development department and design bureau.10

4In the autumn of 1952, Niko Kralj, who is today considered the pioneer and founder of Slovenian industrial design, also drew up the programme for the first Yugoslav factory service for design and development. In the same year, he also produced the first prototype of a foldable recliner, the Rex chair, nowadays one of the best-known products of Slovenian industrial design. In addition to the Rex chair, Kralj developed other chairs as well, such as the 4455 chair, which represents the first true example of an industrial product made entirely in an industrial way in Slovenia, and the Lupina chair series. The Rex chair, made using the pressed and perforated plywood technology, is still considered as an example of an ergonomically and functionally flawless product. It is an iconic piece that has a place in the collection of the Design Department at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.11

5In the 1960s, design asserted its position in society with the establishment of various institutions. The architect Edvard Ravnikar, who was aware of the significance and role of design in the broader social context, criticised the post-war system of architectural education as early as in the 1950s. He also expressed the need to reform it. He believed that architects should expand the spectrum of their work, from designing “the smallest consumer products to planning regional spatial solutions.” In 1959, as part of the education reform, he reached an agreement with the rector of the University of Ljubljana to draw up a radical plan for the reform of the Department of Architecture. As the head of the Faculty of Architecture, he ensured the establishment of the A course (Architecture) and B course (Design) in 1960.12 Based on the Bauhaus models and the contemporaneous Ulm College, the B course was thus introduced on a trial basis in the academic year 1960/61. By implementing the experimental B course of the architecture studies programme, which he carried out for only two years (1960–1962) as an alternative to the conventional system of education at the faculty, Ravnikar monitored and critically evaluated the current issues and placed them in a broader historical, cultural, and contemporary professional context. He ensured that new information was disseminated swiftly within the borders of the former Yugoslavia. He also provided up-to-date information on the achievements of the architectural profession in Western Europe, Scandinavia, and Finland. The B course left its mark on the history of Slovenian design. By combining various scientific disciplines like sociology, psychology, statistics, and geography with certain specialised fields such as urban sociology or social medicine, by bringing together theory and practice, and by using the methodology based on analysis, research, and experimentation, Ravnikar influenced the training of many architects as well as industrial and graphic designers of the post-war generation, despite the fact that the B course was rather short-lived.13

6In the Slovenian part of Yugoslavia, the formal study of industrial design was, as we have already mentioned, introduced in 1984 at the Academy of Fine Arts with the establishment of the Department of Design and its various design courses (industrial, graphic, unique). One of the initiators of this Department’s establishment was Saša Janez Mächtig, the author of the K67 Kiosk and the protagonist of this article.

7More and more active initiatives were launched to establish connections between industrial design and the economy. After unsuccessful attempts to establish a Centre for Industrial Design in Ljubljana, at the initiative of the Ljubljana City Council and the Ljubljana Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Biennial of Industrial Design (BIO) was organised in Ljubljana in 1963, bringing together the positive forces from the economic, political, cultural, and professional circles. The newly established Biennial was intended to increase the quality of industrial design and educate the general and professional public through its exhibition activities, while the goal of the Design Centre was to connect designers with the industry. Since then, this international event – an exhibition of well-designed industrial products, visual messages, and design concepts – has been held in Ljubljana every two years, in the years when the Graphic Design Biennial is not taking place. In the former Yugoslavia, design centres were established in Zagreb (Centar za industrijsko oblikovanje – Industrial Design Centre – in 1964) and Belgrade (Dizajn-Centar – Design Centre – in 1972).14 In 1966, Niko Kralj founded the Institute of Design at the Faculty of Architecture and Civil and Geodetic Engineering. In the framework of the Institute, which he headed until his retirement in 1992, Kralj used a modular industrial approach to research ready-to-assemble and separable industrial units or systemic furniture and contributed to the development of design theory.

8Design became increasingly integrated into companies. The leading role was assumed by Iskra from Kranj – the largest electronics, electrical engineering, measuring instruments, drills, telecommunications, consumer goods, etc., company in the former Yugoslavia. In 1962, under the leadership of the designer Davorin Savnik, Iskra opened the first design department in Yugoslavia for developing the industrial, graphic, and unique design. It became a model for Yugoslav design. Iskra’s industrial designers also created distinctive products, especially in the fields of telephony, measuring instruments, and power tools. The ETA 80 telephone, designed by Davorin Savnik in 1978, was the most successful example. With the advent of the electronic circuit, the designer wanted to create as flat a design as possible.15 In 1980, the world’s first phone with a single microchip won the Design Award IF (Industrie Forum) at what was then the world’s largest industrial trade fair in Hannover and the highest industrial design award in Japan. ETA 80 also became the official telephone of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.16 Later, it was also included in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

9In residential architecture, where the primary focus after the war was to provide everyone with a decent housing minimum, we should also mention the leading researchers of residential culture, the architects Marta Ivanšek and her husband France Ivanšek. Fascinated by the humane spirit of modernism and the high standard of living in Sweden, they wanted to transfer and implement their knowledge of and experience with living in Sweden into the Slovenian environment by raising awareness and educating not only the users but also the professional public. To improve the housing culture in Slovenia, they argued in favour of standardising housing construction, residential spaces, and furniture dimensions. They also designed the Svea kitchen, which became a symbol of modern Slovenian kitchen design.17

10In the 1960s, the general developments and the increasing living standard gave rise to a need and desire for well-designed products that were accessible to everyone. A lifestyle that emphasised youthful and unusual shapes took hold. People were excited about new materials and technologies. After the first wave of the construction and reconstruction of buildings destroyed and damaged during the war, the conditions for the emergence of advanced architectural and urban planning projects were created.

4. The K67 Kiosk System

1The K67 Kiosk is an example of urban street architecture design, envisioned in 1966–1969 by the young Slovenian architect and industrial designer Saša Janez Mächtig.18 He got the inspiration for it from the cross-section of two pipes. Two pipes running through each other in installations reminded him of a construction. With the mutual piercing of two plastic tubes, he began to test the possibilities of a modular system that would correspond to the development of new contemporary technologies and materials at the time in the direction of mass industrial production of products for everyday life. By trimming and machining the tubes, he obtained a module.

2The K67 Kiosk is an artistic design product developed in parallel with other projects of Yugoslav functionalism in the context of the urban environment systematisation through the disciplines of architecture, design, and urban planning.19 It was created at a time of the expansion of modern lifestyles, increased mobility, and the rise of consumerism. At that time, Yugoslavia was reorienting itself towards the production of consumer goods in an effort to promote the activities that contributed to the improvement of the living standard. It also started to promote tertiary activities such as the hospitality industry, tourism, trade, crafts, housing, municipal utility services, and other non-economic activities.20 However, in architecture and design, new practices and approaches were encouraged in the context of the new socio-political and economic system.

3The young architect and industrial designer started designing the K67 Kiosk when he was challenged to solve the needs of Ljubljana, the Slovenian capital. Experts saw inadequate street furniture as a pressing problem. Among other things, they characterised the existing kiosks as unsuitable. With Mächtig’s project of prefabricated spatial elements of the kiosk type, which he developed as street furniture for the needs of minimal commercial, labour, and other service activities for the market for the contemporaneous Ljubljana company Magistrat, he offered an answer to the problems of urban furniture in Ljubljana. As an architect interested in both urbanism and industrial design, he wanted to develop urban street architecture as an organised system. With modular kiosks, he wanted to influence the local authorities, convinced that such a solution would achieve a higher level of standardisation and harmonisation in the city, as he perceived design as a hybrid of the humanities, technical sciences, social sciences, economics, and psychology. He also based his efforts on the principles of Edvard Ravnikar, a professor and architect at the Faculty of Architecture and Civil and Geodetic Engineering in Ljubljana, who advocated, among other things, the principle: “ Think globally, act locally”.21 Aware that he needed to combine not only function and expression but also economics and technology, Mächtig carried out a study of the urban space and the needs of the city’s inhabitants. As an architect, he understood the relationship between products, consumers, and the environment.

4The complex path of the K67 Kiosk’s development began in 1966, when the young architect, based on a few PVC models painted red, started to look for different ways of assembling a system of five interconnected modular elements. These were to be derived from the main crosswise model. The clear geometric format of the crosswise unit was dictated by the design. Mächtig was also aware that the system, as a product, needed to be developed in accordance with the triangle of the design process, consisting of invention, technological production, and marketing.22

5He actively put himself in the role of a marketer and promoter. He proposed that the Imgrad company from Ljutomer – the company that started producing the Kiosks – introduce an internal newsletter titled Kontakti and brochures called Informacije. Both Kontakti and Informacije were, among other things, intended to promote products and, above all, help penetrate foreign markets.23

6According to the opinion of some, with the design and material, as well as colour, Mächtig decided to make the K67 Kiosk outstandingly eye-catching. He associated it with the trend of brightly coloured plastic objects, which reinforced the cult of accessories whose colours and forms represented a reckoning with the traditional grey functionalist past.24 As production developed, the K67 Kiosk started to appear in other colours as well, as customers imagined the colours of the Kiosks according to the activities they were intended to serve.25

7The K67 Kiosk system was the result of socialism with elements of the market economy and the beginnings of a private market economy in the 1960s. Its position and transformative capacity opened up much room for it to function in various social, political, and economic contexts.26

8Working outside the constraints of a single discipline, interdisciplinary integration, the multifunctionality of objects, the inseparability of design from the society, the considerable importance of research, education, and collaboration between the university and the industry, and the necessity of the interplay between design and architecture were all of crucial importance for Mächtig’s way of thinking and practice of design. The K67 Kiosk was a modern object, as it could be folded, disassembled, and transformed. It represented a structure and exhibited features that were considered modern at the time. In the 1960s, the idea of modularity was prominent. The whole world was looking for modular solutions, as a lot of potential was seen in industrial architecture. The search for modular solutions was supported by technological advances in the aerospace industry, which was undergoing revolutionary changes at the time. The K67 Kiosk was created at a time of the dynamic development of the modern way of life, the progress of science and technology, the rise of motorisation, the media, and the birth of a socialist consumer society.27

9The 1960s were an extraordinary period for the development of architecture. Alongside the utopian projects that emerged abroad and in various geographical and cultural contexts as alternatives to the established ways of living, in Yugoslavia, architecture using a refined and specific language of late modernism developed. The K67 Kiosk reflects Mächtig’s belief in technology, mass production, systematic urban growth, infrastructure, and flexible, dynamic, and mobile structures. He drew on the current architectural movements of the time.28

10The K67 Kiosk was realised in the sense of mass production and broad use for service activities in the street. It was created in the region located between East and West – in the space that allowed for mutual cultural exchange. With ideas of temporariness, mobility, adaptability, and prefabrication, the 1960s architecture often approached the discipline of industrial design. The K67 Kiosk represents a fusion of architecture and industrial design as well. It is associated with architecture primarily through space, scale, and function. Meanwhile, its modular structure, production method, materiality, and image correspond to the principles of industrial design. When the conceptual design was first presented in 1967, Saša J. Mächtig wrote that “ the Kiosk, understood in the modern sense, allows for growth and change. Regarding its meaning, it is similar to Scandinavian furniture systems, while in terms of its design feeling, it is akin to a car body.”29 The K67 Kiosk – whose design was friendly, cute, heartwarming, revolutionary, and bold for the times – embodied inventive modular construction with the slogan “a single solution for all problems” and the following instructions for use: “Buy, set up, operate!”30

11As the modular Kiosk was a technical innovation, it was patented in 1967 and named K67 after this year. In 1968, it was prepared for serial production by a company Imgrad from the north-eastern part of Slovenia, where it was manufactured and exported until 2000 after the company had purchased the patent from the Ljubljana-based marketing company Magistrat International. It was first presented to the Slovenian public in 1969 with the exhibition of a prototype in the Slovenian provincial town of Ljutomer. In 1970, after it was featured in the most competent design magazine in the world – the British Design magazine, followed by a wave of international publicity around Europe, the USA, and Japan – it also enjoyed a major marketing boost.

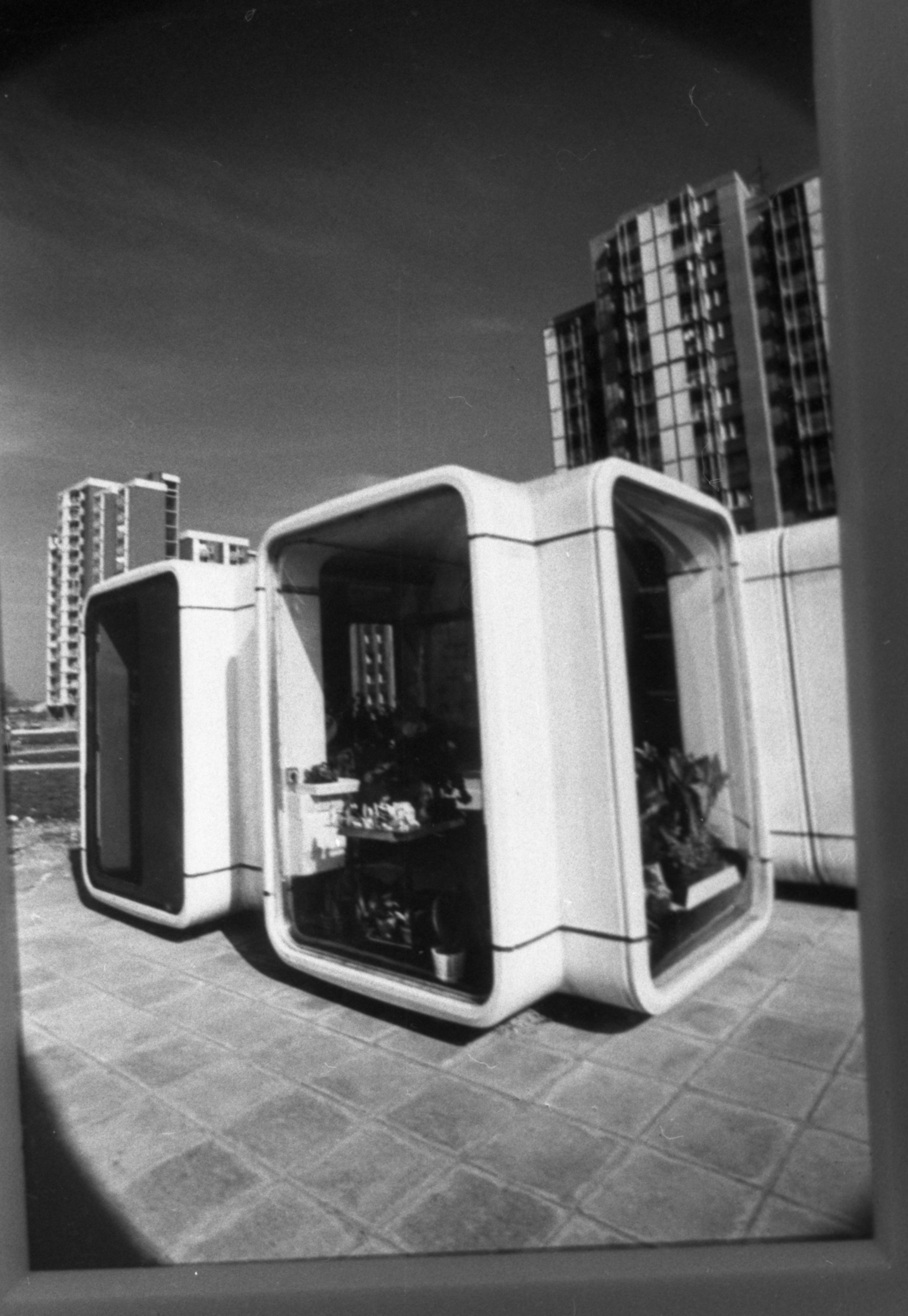

12As the first generation of the K67 Kiosk, made of reinforced polyester and polyurethane in a “sandwich” construction, did not anticipate such a high demand, the architect, soon after this success, developed a composite kiosk construction: the second-generation K67 Kiosk. The first generation of the K67 Kiosk system was characterised by the monolithic form of its primary spatial elements and based on five modular spatial elements, three of which – the cross, the corridor, and the triangular elements – were mass-produced and could be expanded, complemented, and shifted to form various spatial configurations. The primary elements were complemented by a series of secondary, tertiary, and quaternary ones, ranging from various façade fillings to canopies and interior furnishings. The structure consisted of a double shell of reinforced polyester and intermediate insulation.31

13The second generation of Kiosks introduced technological improvements and optimised the production process. The key innovation was the construction of a slightly convex load-bearing shell, which, unlike the original monolithic structure, could be dismantled. The basic elements of the second-generation Kiosk were the ceiling, floor shell, and four corner columns. Side components such as shop, window, door, and blank façade elements could be inserted between them. With the second generation of Kiosks, the designer reduced the production time and simplified transport. For the second-generation Kiosk, the thickness of the elements was increased to 10 cm from the previous 8 cm. The basic unit of the K67 street furniture system became the zero series; while the new unit, which replaced the basic unit in 1972, is the best known today.32

14After 1976, intensive specialisation of the K67 Kiosk system took place. The K67 Kiosk was used for newspaper and tobacco shops, small workshops, florists, parking ticket facilities, information offices, tourist offices, porters’ lodges, etc. Special projects of bivouacs for mountain shelters, standardised hydrometeorological stations, and the project of a Kiosk with a container for selling fruits and vegetables were developed as well. Among the completed projects, the following, which were the most demanding in the technical sense, stood out: Kiosks as reporter booths at the Kantrida Stadium in Rijeka, Croatia; K67 elements as sanitary facilities; transparent triangular units for the police; and the food Kiosk projects. Food Kiosks included units with the equipment for the quick preparation of snacks and drinks, storage, self-service machines, and toilets. In 1980, a test Kiosk specialising in food was set up at Ljubljana Castle in the capital of Slovenia, called Lačni zmaj (Hungry Dragon). In 1977, during the K67 Kiosk’s specialisation, its author Saša Janez Mächtig explained in the factory newsletter Kontakti that “the Kiosk, which is the most demanding element of street furniture in terms of volume, represents the core and starting point for a more comprehensive micro-location layout, as it brings together a number of accompanying functional elements of the equipment – such as wastebaskets, information elements, advertising graphics, lighting, greenery, benches, etc. – all in accordance with the requirements of the specific location, of course.”33

15Large quantities of the K67 Kiosk were sold throughout the former Yugoslavia and elsewhere. It was copied by other manufacturers as well, and it can be said that it embodied the Eastern European kiosk culture. The K67 Kiosk as a unifying and unified object was compatible with the system that did not allow the free market mechanisms to operate. The time in which it was conceived called for rationality and economy. Using a single solution for several purposes was therefore very appropriate. With its multifunctionality, the K67 Kiosk became a characteristic urban space object in the Eastern European socialist countries. At the height of modernist architecture, it was defined as an international style, as it was easily adapted to both Western capitalism and Eastern communism. Today, it is spread all over the world in 7,500 iterations. It was sold to the countries of the former Soviet Union and to the West (to Germany, Switzerland, France, the United States of America, Canada), the Middle East (especially to Iraq and Jordan), as well as to Kenya, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan.34

16The K67 Kiosk represented a breakthrough innovation, as before the rise of industrialisation and the development of new technologies, kiosks would mostly be built as mini-architectures or small houses using ordinary construction methods rather than as products designed and produced according to the industrial logic of mass production. The Kiosk module defined the scope of the workspace: its dimensions were intended for a minimal workspace. By designing the cell, Mächtig worked within the constraints of the existing system and in the direction of discovering further needs. He systematically looked for concrete solutions and attempted to put them into practice.35

17He was system-oriented in his planning, developing all projects as branching systems of variations and combinations that would often go beyond the scope of the individual tasks. The systemic orientation was based on the growing needs to take into account the individual wishes of the users as well as on the contemporaneous structuralist architectural projects during the 1960s and 1970s.36 As a capsule architecture project, the K67 Kiosk is also a clearly structured system whose modular elements provide numerous possibilities for assembly, growth, and adaptation.

Photo: Janez Pukšič, from the photographic collection of the Delo newspaper, kept by: MNZS

18The K67 Kiosk system was based on a series of hierarchically designed components. The primary elements were defined by the supporting structure represented by the various housing models, while the secondary elements or components such as windows, walls, and doors were inserted into the supporting structure. The housings allowed for horizontal as well as vertical stacking into linear or spatially varied combinations. The broad range of accessories allowed for even greater variability. Together, these elements formed diverse spatial structures and embodied the constant potential for change and growth.37

19As micro-architecture fascinated by the introduction of new materials, the K67 system challenged the social, production-technological, and market aspects of the development of street furniture and became a part of the general urban culture, especially in Eastern Europe. It represented temporary modernism at a time when monumental modernism was on the rise in the former Yugoslavia. As temporary installations in the public space, the Kiosks were strategically adapted to the flow of people. The K67 Kiosk system highlighted the commercialisation of space as an important urban value. It was a substantive invention, pointing out the new values in society.38

20The work of the architect and industrial designer Mächtig is inseparably linked to the concept of streets and street furniture. The significant impact of the K67 Kiosk in the Slovenian territory in the 1960s was based on the connection between modular architecture and urban service activities. With its flexible, multifunctional structure that could be infinitely expanded in countless assemblies and configurations, the K67 Kiosk, with its smooth plastic shell, became a distinctive street feature of many urban centres. On the occasion of the exhibition dedicated to the Kiosk in the Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana (26 November 2015 – 3 April 2016), the organisers wrote that the artist as a designer was well-aware of the social significance of street furniture design and therefore also understood that its elements dictated the pulse of the city and influenced the quality of the citizens’ everyday life.

21The K67 Kiosk has become and remains an attribute of the Slovenian architect and designer Saša Janez Mächtig and one of the historical milestones of Slovenian design.

22The red kiosk, as it came to be known, also existed in white, green, yellow, orange, and blue versions. The citizens of the former Yugoslavia still remember it as a red kiosk selling hot dogs and sausages.39

23The Kiosks provided space for activities that did not require a permanent location. They became spots that sold newspapers and tobacco, fast food, snacks, ice cream, flowers, tickets, and so on. They were used to pay parking fees and provide tourist information, as well as functioned as gatehouses in front of various establishments. They were also used by shoemakers, locksmiths, and sports commentators, served as shelters and reception areas, as well as provided room for security guards and reception units.40 In the mid-1980s in Novo mesto, the capital of one of Slovenia’s provinces, seven units of the K67 Kiosk made up the Slavček bar, for example. The establishment was set up by a restaurateur from Novo mesto together with his wife, a cook. As it happened, the K67 Kiosk was the cheapest option for building a pub at the time. The couple bought seven of them and assembled them into a structure. Then they also excavated a basement. The Slavček bar, which was later sold by the owners’ son, was probably the only K67 Kiosk with a basement in the world.41 K67 Kiosks hosted small private businesses even before the collapse of the state and the system – even before the transition to a free-market economy in the 1990s.

24Subject to constant adaptation and temporariness, the K67 Kiosk was present in the public space and asserted its personal modernism. Designed primarily for urban areas, it was conceived as a project to systematise the urban environment. It was designed as an open structure, capable of change. It could be connected to the infrastructure network – connections such as water, sewerage, electricity, and telephone. This included the possibility of underground installations to avoid interfering with the design of the module itself. Pre-manufactured on a component-by-component basis, it arrived fully assembled and ready to be connected to the existing installations. Using new technologies and materials that were in vogue at the time – such as reinforced polyester and polyurethane – it was an innovative and practical solution. The elements of the K67 system combined with complementary street furniture units such as wastebaskets offered a wide range of possibilities to create an identity for a wide variety of environments. The Slovenian architect and designer also derived other street furniture systems from the open structure of the Kiosk, implementing them as a connecting element of the city and contributing to its comprehensiveness, recognisability, and better orientation.42

5. Breakthrough and International Visibility

1A review of the K67 Kiosk in the English Design magazine – according to the kiosk’s author, it was the first industrial design magazine at the time in the world – represented the first international recognition of architect Saša Janez Mächtig and his now iconic Kiosk. In 1969, the Slovenian architect attended a congress of the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID World Design Congress) in London, where he met many publishers, editors, and contributors of the Design magazine. As they were interested in his work, he showed them the slides made for the exhibition of the prototype Kiosk at the location of its construction. In the spring of 1970, he received a copy of the Design magazine with a two-page review of the K67 Kiosk with a full-page colour photograph titled Low life from the streets. The Kiosk was presented as an example of urban design. It was also included in the list of the 25 best-designed Yugoslav products. It was ranked 11th on the list that the renowned design theory expert Goroslav Keller compiled for the Start magazine. After the review in the Design magazine, the K67 Kiosk was invited to be included in the collection of one of the most influential modern art museums in the world, the New York Museum of Modern Art, MoMA. In 1970, the latter was preparing an exhibition of Italian design, a part of which was devoted to modular industrial architecture. Many top Italian designers were invited. When the organisers noticed that modular architecture was also emerging elsewhere, they offered to include the K67 Kiosk into the MoMA collection. Technological, social, or aesthetic innovation are among the main criteria for the inclusion of works into this collection, as the Museum is dedicated exclusively to modern art and aims to integrate diverse artistic practices into its programme, with architecture and design representing crucial parts of this effort.43 In 1971, the K67 Kiosk became the second Yugoslav product alongside Marko Turk’s microphone44 to be included in the collection of the world’s first museum of contemporary industrial design. The MoMA Museum curator placed it in the Environments category. The curator’s design programme and the way of setting up the forthcoming exhibition of Italian design titled Italy: the New Domestic Landscape, Achievements, and Problems of Italian Design, organised by the MoMA Museum, both emphasised the environment. The 1972 exhibition of Italian design included the concept of environments as one of its key themes. The participants were asked to propose micro-environments within the spatial constraints of 3.6 metres in height, 4.8 metres in width, and 4.8 metres in depth. Each environment had to be prefabricated and packed in a standard shipping container. The exhibition of Italian design and the K67 Kiosk represent important milestones in the design development of these achievements, as they take into account industrially produced individual units as well as the urban whole. The exhibition of Italian design, which promoted new talents and encouraged the exploration of innovative design practices, expressed a desire for change through a combination of critical interventions and radical and practical solutions. It was one of the landmark design exhibitions of the 20th century.45 The inclusion of the K67 Kiosk in the collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art – with its tradition of collecting and presenting architecture as a replicable object of design and a crucial contributor to the discourse on sustainability, architectural invention, material research, and urbanism – represented an incredible breakthrough as well as a challenge in terms of planning the exportation of the Kiosks.

2Unfortunately – due to a fire in the Imgrad company, which produced the Kiosks – the Slovenian architect and industrial designer was only able to take limited advantage of the significant international recognition of the K67 Kiosk when it won the global competition for street furniture in the Munich pedestrian zone and for certain other needs of the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, Germany. Thus, only the Olympic Sailing Centre in Kiel was equipped with K67 Kiosks.46

6. The Kiosk’s Second Life

1The second life of the K67 Kiosk refers to the phenomenon of the Kiosk today. Nowadays, it appears in various roles: as an icon of the 20th-century industrial design and a coveted collectors’ item; a decayed and abandoned object in the cities of South-Eastern Europe; a nostalgic memory of youth and socialism; a phenomenon and foundation for research and artistic projects; as well as a live organism capable of constant regeneration.47 As an artistic artefact, it has its place in museums and books, and it is also food for thought. Because of its social function, it became a part of the collective consciousness and memory. With its colours and presence, it made a profound impact on its surroundings. As urban street architecture set in the public space, it promoted the everyday activities of the street or everyday space.48 In the opinion of the Slovenian artist Marjetica Potrč, it was a substantive invention and a living laboratory in the right place at the right time.

2Due to its distinctive character, the Kiosk still possesses a strong image today. As an accent, it is integrated into either historical or contemporary environments on unexpectedly equal terms.

3Since as early as 1971, the K67 Kiosk has been included in the collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) as a retrospective of the best examples of 20th-century design. In 2018, it became a part of the MoMA Museum’s major retrospective exhibition titled Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980. In the context of a Times Square Design Lab project,49 a K67 Kiosk also appeared in Times Square in the heart of New York City and remained there until the middle of the spring of 2019. At the intersection of the 45th and 46th Streets and Broadway, it served as an information hub for the Times Square design pavilion and the NYCxDESIGN event.

4When the Kiosk was set up, Tim Tompkins, President of Times Square Alliance, which manages the public space of this New York’s square, said the following: “We like the Kiosk so much that we bought it and brought it here to keep it forever. We do not know exactly what to put in it yet, because it can serve many purposes – as a tourist information spot, selling food and drink, or maybe books and newspapers. But first, it will provide tourist information.”50

5At the client’s request, the author, in collaboration with skilled contractors, had the Kiosk restored to its original 1966 colour combination: bright red for the main structure and dark brown for the prefabricated walls.

6The President of Times Square Alliance further explained: “Half a million people pass through Times Square every day, so this is a great venue for promotion. We would like to bring a bit of Europe to the new world, some beauty to a less beautiful place, and, if you like, some socialism to this centre of capitalism.”51

7Currently, K67 Kiosks are being revived in some places. Thanks to their construction and modular system, which allows for addition, subtraction, modification, and upgrading, the Kiosk is nowadays often used in completely new functions. Well-preserved specimens are highly sought-after and are being restored. For example, the German designer Martin Ruge von Löw became interested in the Kiosk when he came across it in Poland. He decided to search for the product and restore it. At his initiative, in September 2018, a K67 Kiosk started operating in Berlin as the city’s smallest restaurant in the open-air inner square of the Art Nouveau Mykita complex in the iconic Kreuzberg district.52

8Furthermore, in 2007, the University of Weimar brought a Kiosk from Warsaw and used it as an information point in front of the building where the first Bauhaus school had been located.

9The transformative capacity of the K67 Kiosk was most evident in the context of “do-it-yourself” projects, unplanned individual initiatives, and various processes of self-organisation. In this context, the K67 Kiosk appears as a kind of folk architecture. The practice revealed all that was unpredictable, changeable, and temporary. On the one hand, the Kiosk appears as an object belonging to a planned city – a city adhering to a set of modern planning rules – while on the other hand, it appears as an object belonging to an “open city” – a city that allows and enables random changes and developments.53

10Some people underline it as a system that, with its design, still offers universal solutions today. The abovementioned internationally active Slovenian artist Marjetica Potrč calls it strategic architecture. Her art installation Next Station Kiosk, presented in 2003 at the Ljubljana Modern Art Museum, presents the idea or potential of a mobile dwelling. With this installation, Potrč answers a provocative question posed by the English Design magazine, which, when the Kiosk was unveiled in 1970, wondered whether the architect would be able to develop the K67 system in the direction of becoming a dwelling,54 as, at the time when the K67 Kiosk was created, it was natural to think about mobile housing units for the mobile individual. For example, in America at the time, temporary mobile architecture – such as the poor living in trailers – was formally compared, in the pejorative sense, with the informal city, which was perceived as a place of chaos and disorder.55

11Because it was so widespread, the K67 Kiosk, which some critics described as dispersed network architecture, was also researched by Helge Kühnel from Berlin for Amsterdam’s Publicplan.

12“The Kiosk Shots” project, initiated by Publicplan Amsterdam, aims to evaluate the K67 design product and draw attention to its exceptional role in the Eastern European urban environment. The project of collecting and mapping the K67 Kiosks intends to create a general overview – documentation about the Eastern European urban environment. The project, whose purpose is to demonstrate the individual diversity and variety of a design product placed in a public environment, will provide a virtual online overview of the presence of the K67 Kiosks scattered throughout Eastern Europe (at www.publicplan.com/K67).56

13The process of the evaluation of the K67 Kiosk is also accompanied by a number of artistic projects. In addition to the abovementioned Slovenian artist Marjetica Potrč, who combined K67 units with South American “palafitos“ – wooden houses raised on stilts – in her installation “Next Stop Kiosk”, Magnus Bärtås, a Swedish artist ˮ, arranged K67 units in front of a black background in his photo series “Satellitesˮ. The important role of the Kiosks in the former Yugoslavia was also documented by the project “Mutations” a few years ago. Above all, the K67 Kiosk has become a part of the history and identity of the former Yugoslavia and also a part of a wider and global design heritage.57

14In 2013, the K67 Kiosk was also issued as a commemorative stamp from the Slovensko industrijsko oblikovanje (Slovenian Industrial Design) series. On the occasion of the stamp’s presentation, a K67 Kiosk was set up in the courtyard of the Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana, where a Post of Slovenia counter operated. The counter sold the newly issued postage stamps as well as a commemorative stamp “ K67 Kiosk – Day One”.58

15The revival and restoration of the Kiosks are quite important for Slovenian design. The retired director of the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Novo mesto decided to preserve the seven units of the abandoned K67 Kiosk that had made up the former Slavček bar, which I already mentioned in this article and which were, until recently, waiting for better times. He persuaded several institutions to join him in the attempt to save the Kiosks and negotiated a donation with their last owner. The Novo mesto unit of the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage provided the required storage space, while the Lower Carniola Museum took on the role of the recipient of the donation. The Mayor of Novo mesto also participated in the coordination with the companies technically involved in the decommissioning and transport. They also sought advice from Saša Janez Mächtig, the creator of the K67 Kiosk, and from the private car painting and body repair company that restored the K67 Kiosks now exhibited in New York, Berlin, Zurich, and elsewhere. The idea is to soon reopen the renovated Slavček bar at a suitable location in Novo mesto.59

16Currently, the industrial designer and architect Mächtig is drawing on the experience with the functionally and commercially successful K67 Kiosk to design the new K21 system of modular multifunctional self-service units. The new generation of Kiosks is also designed in a systemic way, with modular biomorphically shaped basic units derived from structures and patterns from nature. Once again, the architect envisioned the individual units meeting the minimum requirements of modern working and living. The new Kiosk’s use is expected to be similar to that of the first and second-generation Kiosks. It will be possible to use it for mobile homes, information points, small cafés, retail, and other service activities. The architect envisaged that the wall elements or fillings of the 21st-century Kiosk could be designed as information displays, while solar panels could be installed on the roof to ensure energy independence.60 In February 2019, he presented the system at the Architecture Inventura 2019 exhibition in the large reception hall of the Cankarjev dom cultural and congress centre in Ljubljana. The Slovenian designer says his Kiosk is an example of an industrial product for the people, that it has not changed over the years, and that it still fulfils the purpose of providing people with the minimum workplace. Progress has not tossed it aside, and the Kiosk design from the year 1966 has survived.61

7. Conclusion

1With its flexible modular multifunctional structure, the possibility of infinite expansion in countless assemblies and configurations, and its smooth plastic shell, the K67 Kiosk system, designed by the Slovenian industrial designer and architect Saša Janez Mächtig in 1966 as a project of prefabricated spatial elements of the kiosk type for the needs of minimal commercial, labour, and other service activities for the market, has become a characteristic street feature characterising many urban centres, especially in Eastern Europe. As micro-architecture fascinated by the introduction of new materials, it challenged the social, production-technological, and market aspects of the development of street furniture and became a part of the general urban culture. The significant impact of the K67 Kiosk in the Slovenian territory at the time of its creation was based on the connection between modular architecture and urban service activities. Thanks to its open structure and multifunctionality, the versatile, modularly designed K67 Kiosk was easily integrated into a variety of environments.

2Nowadays, it appears in various roles: as an icon of the 20th-century industrial design and a coveted collectors’ item; an artwork in museums and books; a decayed and abandoned object in the cities of South-Eastern Europe; a nostalgic memory of youth and socialism; a phenomenon and foundation for research and artistic projects; as well as a live organism capable of constant regeneration. The hybrid architectural and industrial design object has become a cult product and a part of the collective consciousness and memory.

Literature and Sources

- MNZS − Muzej novejše in sodobne zgodovine Slovenije:

- Fototeka.

- »Natečaj za stanovanjske bloke v Ljubljani.«Arhitekt 6, no. 18–19 (1956): 7.

- »Za napredek naše arhitekture.« Arhitekt 1, no. 1 (1951): 1.

- »Za novo arhitekturo.« Arhitekt 3, no. 8 (1953): 1.

- Hrausky, Andrej. »Poti sodobne slovenske arhitekture.« In Slovenska kronika XX. stoletja, edited by Marjan Drnovšek and Drago Bajt, 364–366. Ljubljana: Nova revija, 1997.

- Interno študijsko gradivo za predmet Razvoj in teorija oblikovanja. Ljubljana: ALUO.

- Kinchin, Juliet. »Zbirka inovativnih oblikovalskih praks.« InSistemi, strukture, strategije, edited by Maja Vardjan, 81−84. Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje: Akademija za likovno umetnost in oblikovanje, 2016.

- Leban, Pika. »Bienale industrijskega oblikovanja od ustanovitve leta 1963 do načrtov za prihodnost.« Thesis, Univerza v Ljubljani: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2009.

- Mächtig, Saša J. »Fenomeni v urbanskem okolju.« Kontakti, 1, 1977.

- Mächtig, Saša J. »Kiosk K67, I. generacija.« In Sistemi, strukture, strategije, edited by Maja Vardjan, 102−115. Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje: Akademija za likovno umetnost in oblikovanje, 2016.

- Mächtig, Saša J. »Sistem Kiosk 21.« In Sistemi, strukture, strategije, edited by Maja Vardjan, 214, 215. Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje: Akademija za likovno umetnost in oblikovanje, 2016.

- Mächtig, Saša J., and Paldi, Livia. »Sistem K-67. Intervju s Sašo J. Mächtigom.« In Next Stop Kiosk = Naslednja postaja Kiosk: Moderna galerija Ljubljana, 29. 10. – 30.11. 2003, 148−151. Ljubljana: Moderna galerija = Modern Art Museum; Frankfurt am Main: Revolver – Archiv für aktuelle Kunst, 2003.

- Malačič, Janez. »Razvoj prebivalstva Slovenije v povojnem obdobju.« Teorija in praksa: družboslovna revija 22, no. 4–5 (1985): 402–414.

- Malešič, Martina. »Arhitekta France in Marta Ivanšek.« In Arhitekturna zgodovina, 166−75. Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete, Zavod za gradbeništvo Slovenije, 2008.

- Mercina, Andrej.Arhitekt Ilija Arnautović: Socializem v slovenski arhitekturi. Ljubljana: Viharnik, 2006.

- Panič, Ana. »Kiosk K67 ali blišč in beda nekega razvojnega preboja.« In Made in YU 2015, edited by Tanja Petrović and Jernej Mlekuž, 154−163. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, ZRC SAZU, 2016.

- Panter, Mateja. »K67, kiosk, ki je po 50 letih spet oživel. Po evropskih mestih spet srečujemo legendarni kiosk slovenskega oblikovalca in arhitekta Saše Janeza Mächtiga.« Dnevnik, July 9, 2018. https://www.dnevnik.si/1042832279.

- Potrč, Marjetica. »Kiosk je bil fenomen.« InSistemi, strukture, strategije, edited by Maja Vardjan, 77−80. Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje: Akademija za likovno umetnost in oblikovanje, 2016.

- Rendla, Marta. »Hitro, gospodarno, po meri: sestavljivo sistemsko pohištvo v socializmu.« In Mimohod blaga. Materialna kultura potrošniške družbe na Slovenskem, edited by Andrej Studen, 165−85. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2019.

- Rendla, Marta. »Kam ploveš standard?« Življenjska raven in socializem. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2018.

- Šubic, Špela. »Oblikovalec Saša J. Mächtig.« InSistemi, strukture, strategije, edited by Maja Vardjan, 65−76. Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje: Akademija za likovno umetnost in oblikovanje, 2016.

- Vardjan, Maja. »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67.« InSistemi, strukture, strategije, edited by Maja Vardjan, 38−50. Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje: Akademija za likovno umetnost in oblikovanje, 2016.

- Vidmar, Igor. »Slavček ni umrl, postal je dediščina.« Dolenjski list, June 6, 2021. https://www.dolenjskilist.si/2021/06/13/249567/novice/dolenjska/Slavcek_ni_umrl_postal_je_dediscina/.

- Zorko, Aleksandra. »Kultni kiosk K67 na poštni znamki.« Deloindom, November 21, 2013. https://old.delo.si/druzba/panorama/deloindom-kultni-kioAndresk-k67-na-postni-znamki.html.

- J. A. Kultni kiosk Saše Mächtiga kraljuje sredi newyorškega vrveža. RTV SLO. Accessed April 17, 2023. https://www.rtvslo.si/kultura/vizualna-umetnost/kultni-kiosk-sase-maechtiga-kraljuje-sredi-newyorskega-vrveza/487724.

- MAO - Eta 8. Accessed May 6, 2023, https://mao.si/zbirka/eta-80/.

- RTV 365, »Naslednja postaja kiosk, Saša J. Mächtig, arhitekt in industrijski oblikovalec.« Accessed April 15, 2023, https://365.rtvslo.si/arhiv/dokumentarni-portret/174746857.

- Saša Maechtig, Kiosk K67, 1966. Zavod Big. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://zavodbig.com/portfolio-items/sasa-maechtig-kiosk-k67-1966/.

- Znameniti kiosk, ki je iz Ljutomera osvajal svet. S slovitim kioskom Kiosk K67 je Ljutomer tesno povezan, saj so te modularne kioske izdelovali v ljutomerskem podjetju Imgrad. Accessed May 11, 2021, https://www.prlekija-on.net/lokalno/20341/znameniti-kiosk-ki-je-iz-ljutomera-osvajal-svet.html.

Marta Rendla

URBANA ULIČNA ARHITEKTURA, KIOSK K67: ENA REŠITEV ZA VSE TEŽAVE

POVZETEK

1V prispevku avtorica na primeru oblikovalskega izdelka, kioska sistema K67, oriše razvoj in vlogo urbane ulične industrijsko oblikovane arhitekture, zasnovane v šestdesetih letih prejšnjega stoletja v nekdanji Jugoslaviji v času dinamičnega razvoja mest in naraščajočih potreb mesta. Umetniški oblikovalski izdelek je nastal po opustitvi centralno planskega socialističnega gospodarstva po sovjetskem vzoru in uvedbi samoupravljanja v petdesetih letih ter njegovem prehodu na gospodarstvo s poudarjenimi elementi trga v šestdesetih letih 20. stoletja. Poudari, da je v okoliščinah socialistične modernizacije slovenske in jugoslovanske družbe kiosk K67 slovenskega arhitekta in industrijskega oblikovalca Saše Janeza Mächtiga zaradi svoje socialne funkcije v oblikovanju javnega prostora in vsakdana ljudi postal brezčasen ter del kolektivne zavesti in spomina državljanov nekdanje Jugoslavije.

2Znameniti rdeči kiosk, zasnovan v duhu poznega modernizma leta 1967, je nastal kot del večjega projekta – mesta. Socialistični koncept urbanega prostora je predvideval družbeno usmerjeno kolektivno gradnjo večstanovanjskih zgradb in sosesk, ki naj bi generirale zavest o pripadnosti skupnosti. Ljudje so se takrat navduševali nad novimi materiali in tehnologijami in v različnih geografskih in kulturnih kontekstih so kot alternativa uveljavljenim načinom bivanja vznikali utopični projekti. Univerzalno zasnovani in modularno sestavljivi kiosk K67 je takrat mladi arhitekt projektiral za potrebe minimalnih trgovskih, delovnih in drugih storitvenih dejavnosti za trg kot cestno opremo za tedanje ljubljansko podjetje Magistrat. Do danes je s svojo široko uporabnostjo in večnamenskostjo umeščanja različnih storitvenih dejavnosti, kot so prodajalne hitre prehrane, časopisja, tobaka, vozovnic, vstopnic, cvetja, recepcije, stražarnice ipd., prehodil kompleksno pot razvoja.

3Do druge polovice šestdesetih let, ko je kiosk začel svoje življenje, je Jugoslavija že imela za seboj povojno obnovo in izgradnjo bazične težke industrije. Intenzivno se je tudi že usmerjala v razvijanje dejavnosti, ki vplivajo na življenjsko raven. Slovenska družba v Jugoslaviji se je preobrazila iz ruralne v industrijsko. Spremenile so se navade, vrednote, odnos do materialnih dobrin, možnosti trošenja in tudi zahteve prebivalstva. Utrjevanje in širjenje sodobnega urbanega življenja tudi izven urbanih okolij, povečana kupna moč in dvig življenjskega standarda so spodbudili odzivanje industrijske proizvodnje na potrebe trga. S pojavom množične motorizacije, razmaha medijev in potrošništva se je gospodarstvo preusmerjalo v krepitev lahke industrije in terciarnih dejavnosti, kot so gostinstvo, turizem, trgovina, obrt, druge storitvene in stanovanjsko-komunalne dejavnosti.

4Kot izziv na reševanje takratnih potreb mesta se je v želji, da bi v mestu dosegli višjo raven standardizacije in harmonije, rodila ideja o modularno zasnovanem mobilnem kiosku- Preživel je vse do danes. V sodobni stvarnosti se pojavlja v različnih vlogah: kot ikona oblikovanja 20. stoletja in zaželen zbirateljski predmet, kot propadel in zapuščen objekt v mestih jugovzhodne Evrope, kot nostalgičen spomin na mladost in socializem, kot fenomen in izhodišče raziskovalnih in umetniških projektov ter kot živ organizem, ki je sposoben nenehne regeneracije. Je na poti vstopa v novo življenje kot K21, interaktivni samooskrbni večnamenski kiosk za enaindvajseto stoletje.

* Dr., znanstvena sodelavka, Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, Privoz 11, SI-1000 Ljubljana; marta.rendla@inz.si

1. Janez Malačič, »Razvoj prebivalstva Slovenije v povojnem obdobju.« Teorija in praksa: družboslovna revija 22, no. 4–5 (1985): 402.

2. »Za napredek naše arhitekture,« Arhitekt 1, no. 1 (1951): 1.

3. Andrej Mercina, Arhitekt Ilija Arnautović: Socializem v slovenski arhitekturi (Ljubljana: Viharnik, 2006), 19.

4. »Za novo arhitekturo,« Arhitekt 3, no. 8 (1953): 1.

5. Andrej Hrausky, »Poti sodobne slovenske arhitekture,« in Slovenska kronika XX. stoletja, ed. Marjan Drnovšek and Drago Bajt (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 1997), 364.

6. Interno študijsko gradivo za predmet Razvoj in teorija oblikovanja (Ljubljana: ALUO), 129.

7. Marta Rendla, »Hitro, gospodarno, po meri: sestavljivo sistemsko pohištvo v socializmu,« in Mimohod blaga. Materialna kultura potrošniške družbe na Slovenskem, ed. Andrej Studen (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2019), 165.

8. »Natečaj za stanovanjske bloke v Ljubljani,«Arhitekt 6, no. 18–19 (1956): 7.

9. Interno študijsko gradivo, 132.

10. Ibidem, 133.

11. Marta Rendla, »Kam ploveš standard?« Življenjska raven in socializem (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2018), 274.

12. Interno študijsko gradivo, 134.

13. Maja Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67,« in Sistemi, strukture, strategije, ed. Maja Vardjan, (Ljubljana: Muzej za arhitekturo in oblikovanje: Akademija za likovno umetnost in oblikovanje, 2016), 39, 40. Mercina, Arhitekt, 19.

14. Pika Leban, »Bienale industrijskega oblikovanja od ustanovitve leta 1963 do načrtov za prihodnost« (Thesis, Univerza v Ljubljani: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2009), 15−19.

15. Interno študijsko gradivo, 136, 137.

16. MAO - Eta 80, accessed May 6, 2023, https://mao.si/zbirka/eta-80/.

17. Martina Malešič, »Arhitekta France in Marta Ivanšek,« in Arhitekturna zgodovina (Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete, Zavod za gradbeništvo Slovenije, 2008), 170, 171.

18. Saša J. Mächtig’s development as an architect and designer was influenced by the B course of the experimental architecture study programme. Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema Kiosk K67,« 39.

19. Ibid.

20. Rendla, »Kam ploveš standard?,« 330, 331.

21. »Naslednja postaja kiosk, Saša J. Mächtig, arhitekt in industrijski oblikovalec,« RTV 365, accessed April 15, 2023, https://365.rtvslo.si/arhiv/dokumentarni-portret/174746857.

22. Saša J. Mächtig and Livia Paldi, »Sistem K-67. Intervju s Sašo J. Mächtigom,« in Next Stop Kiosk = Naslednja postaja Kiosk: Moderna galerija Ljubljana, 29. 10. – 30.11. 2003 (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija = Modern Art Museum; Frankfurt am Main: Revolver – Archiv für aktuelle Kunst, 2003), 149.

23. Špela Šubic, »Oblikovalec Saša J. Mächtig,« inSistemi, strukture, strategije, ed. Maja Vardjan, 71.

24. Ibid., 73.

25. Ana Panič, »Kiosk K67 ali blišč in beda nekega razvojnega preboja,« in Made in YU 2015, ed. Tanja Petrović and Jernej Mlekuž (Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, ZRC SAZU, 2016), 154, 155.

26. Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67,« 38, 39.

27. »Naslednja postaja kiosk.«

28. Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67,« 42.

29. Ibidem, 45.

30. Ibid., 43−45. »Naslednja postaja kiosk.«

31. Saša J. Mächtig, »Kiosk K67, I. generacija,« in Sistemi, strukture, strategije, ed. Maja Vardjan, 102.

32. Šubic, »Oblikovalec Saša J. Mächtig,« 72, Mächtig, »Kiosk K67, II. generacija,« 116.

33. Saša J. Mächtig, »Fenomeni v urbanskem okolju,« Kontakti 1, (1977): 5, 6.

34. Mateja Panter, »K67, kiosk, ki je po 50 letih spet oživel. Po evropskih mestih spet srečujemo legendarni kiosk slovenskega oblikovalca in arhitekta Saše Janeza Mächtiga,« Dnevnik, July 9, 2018, https://www.dnevnik.si/1042832279.

35. Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67,« 43−45. »Naslednja postaja kiosk.«

36. Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67,« 46.

37. Ibid.

38. Marjetica Potrč, »Kiosk je bil fenomen,« in Sistemi, strukture, strategije, ed. Maja Vardjan, 77.

39. Panič, »Kiosk K67 ali blišč in beda nekega razvojnega preboja,« 154, 155.

40. Znameniti kiosk, ki je iz Ljutomera osvajal svet. S slovitim kioskom Kiosk K67 je Ljutomer tesno povezan, saj so te modularne kioske izdelovali v ljutomerskem podjetju Imgrad, accessed May 11, 2021, https://www.prlekija-on.net/lokalno/20341/znameniti-kiosk-ki-je-iz-ljutomera-osvajal-svet.html.

41. Igor Vidmar, »Slavček ni umrl, postal je dediščina,« Dolenjski list, July 7, 2021, https://www.dolenjskilist.si/2021/06/13/249567/novice/dolenjska/Slavcek_ni_umrl_postal_je_dediscina/.

42. Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67,« 47.

43. Juliet Kinchin, »Zbirka inovativnih oblikovalskih praks,« in Sistemi, strukture, strategije, ed. Maja Vardjan, 81.

44. Marko Turk’s microphone was included in the MoMA Museum’s permanent collection in 1963.

45. Kinchin, »Zbirka inovativnih oblikovalskih praks,« 82.

46. Šubic, »Oblikovalec Saša J. Mächtig,« 65.

47. Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67,« 48.

48. Potrč, »Kiosk je bil fenomen,« 77.

49. The Times Square Design Lab is an initiative to implement and test various ideas regarding the public space in the immediate vicinity of Broadway. It provides solutions for seating, public signage, and storage in the squares. In some cases, the initiative involves new design ideas, and in others classic designs sharing the characteristic that they “ embody the creative spirit of New York and offer original solutions for a better pedestrian experience in a busy location”.

50. A. J., Kultni kiosk Saše Mächtiga kraljuje sredi newyorškega vrveža - RTV SLO, accessed April 17, 2023, https://www.rtvslo.si/kultura/vizualna-umetnost/kultni-kiosk-sase-maechtiga-kraljuje-sredi-newyorskega-vrveza/487724.

51. Ibid.

52. Panter, »K67, kiosk, ki je po 50 letih spet oživel.«

53. Vardjan, »Metamorfoze sistema kiosk K67,« 48.

54. Ibid., 48−50.

55. Potrč, »Kiosk je bil fenomen,« 77.

56. »Saša Maechtig, Kiosk K67, 1966. Zavod Big,« accessed May 9, 2021, https://zavodbig.com/portfolio-items/sasa-maechtig-kiosk-k67-1966/.

57. Ibid.

58. Aleksandra Zorko, »Kultni kiosk K67 na poštni znamki,« Deloindom, November 21, 2013, https://old.delo.si/druzba/panorama/deloindom-kultni-kioAndresk-k67-na-postni-znamki.html.

59. Vidmar, »Slavček ni umrl, postal je dediščina.«

60. Saša J. Mächtig, »Sistem Kiosk 21,« in Sistemi, strukture, strategije, ed. Maja Vardjan, 214.

61. Panter, »K67, kiosk, ki je po 50 letih spet oživel.«