Socialist Yugoslavia’s Efforts to Democratise International and Intercultural Communication: a Reappraisal*

IZVLEČEK

PREMISLEK O PRISPEVKIH SOCIALISTIČNE JUGOSLAVIJE K MEDNARODNEMU IN MEDKULTURNEMU KOMUNICIRANJU

1V tem članku predstavljam (ponovno) branje nekaterih svojih raziskav in razprav o množičnem komuniciranju in razvoju socialistične demokracije v Jugoslaviji, objavljenih v zadnjih dveh desetletjih obstoja večnacionalne federacije pred njenim nenadnim in nasilnim propadom. Članek je zasnovan kot ponovna presoja ključnih idej in rezultatov nekaterih empiričnih raziskav, ki sem jih zasnoval in izvajal v sedemdesetih in osemdesetih letih prejšnjega stoletja do osamosvojitve Slovenije leta 1991. Vključujejo več različnih tematik, kot so komuniciranje med republikami v Jugoslaviji, tuja radijska propaganda in delovanje tiskovne agencije Tanjug, zbiranje novic in redakcijsko odbiranje ter razvoj komunikologije kot znanstvene discipline v Jugoslaviji.

2Ključne besede: Jugoslavija, medkulturno komuniciranje, množični mediji, socializem

ABSTRACT

1In this article, I present an annotated (re)reading of selected research and writings on mass communication and the development of socialist democracy in Yugoslavia that I published in the final 20 years of this multinational federation’s existence prior to its sudden and violent collapse. The article is conceived as a reappraisal of key ideas and results of certain research I designed and conducted in the 1970s and 1980s up until Slovenia attained its independence in 1991. They include a range of diverse topics like communication among the republics in Yugoslavia, foreign radio propaganda, news gathering and editorial gate-keeping, the performance of the Tanjug news agency, as well as the development of communication science as a scientific discipline in the federation.

2Keywords: Yugoslavia, intercultural communication, mass media, socialism

1. Introduction

1In this article, I present an annotated reading of selected research and writings on mass communication and the development of socialist democracy in Yugoslavia that I published during the final 20 years of this multinational federation’s existence before its sudden and violent collapse. The article is conceived as a reappraisal of key ideas and results of certain empirical research I designed and conducted in the 1970s and 1980s up until Slovenia’s independence in 1991. They include diverse topics like communication among the republics in Yugoslavia, foreign radio propaganda, news gathering and editorial gate-keeping, the performance of the Tanjug news agency, along with the development of communication science as a scientific discipline in Yugoslavia. This reappraisal is not meant to replace a systematic review and comprehensive analysis of the topics and approaches, unity and differences in mass communication research during socialist Yugoslavia and does not pretend to represent the entirety of media research in the federation. However, a review of my personal research efforts and publications over the last two decades of the former state can reveal at least two things. It first indicates which topics were considered relevant in scientific terms. In addition, given that most empirical research was publicly funded, it also (at least partly) indicates which research topics were then considered socially (and politically) legitimate.

2The Yugoslav communication system(s), like the political system of socialist self-management, was born following the liberation and social revolution completed after the Second World War and after the ideological and political conflict with the Soviet Union and expulsion from the socialist bloc in 1948. The early development of the press and radio in the new Yugoslavia unfolded in the framework of state-party centralism and the revolutionary system of agitation and propaganda, and was burdened by traditional revolutionary notions of the transmission role of the press as part of the political avant-garde of the working class. The steady transition from autocratic communication to forms of socialisation and democratic communication intensified after the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution. Greater autonomy of the constituent federal units (republics) and the self-management of state-owned enterprises and institutions was introduced by the Constitution, yet they remained difficult and controversial. The relationships among the republics were always marked by their great economic and cultural differences. The differences resulting from the different political interests of the republics, which were becoming stronger, led to growing conflicts between them and made it hard to establish common interests and benefits that everyone would recognise, with the ‘national question’, and even the interethnic political conflicts that remained unresolved until the federation’s demise.

3At the same time, ideologised notions of the unreserved and uncontroversial self-governing development of communication, the uniqueness of the Yugoslav socialist paradigm of the future and its incomparability with the development of other social and communication systems in the world were gaining ground in Yugoslavia’s development. The maintenance of a normative ‘understanding’ of development and its planning, which did allow for new perspectives and alternatives to development, was facilitated by the absence of critical self-reflection, a forward-looking consideration of both the future and the ‘outside’ world that we were in permanent – albeit often denied – interdependence. The development of mass communication in Yugoslavia was also challenged from the outside by the developed communication systems of societies that had already moved into the new historical formation of the ‘information society’ with modern information technology and information processes, participatory communication, and a culture of political dialogue. While the socialist authorities had invested in developing media from the very beginning, the lack of economic development, technical infrastructure and skilled journalists in the early stages hampered this development. Inter-republics differences in development were also visible in the increase in communication inequality, while the population’s national and linguistic diversity on the other hand also spurred the development of media pluralism in federal units. Apart from a short period of time in the 1940s, Yugoslavia did not have federal media able to spread the same content across the country: the media, like culture, education and research, was the sole responsibility of the republics and their authorities. The only real exception was television news since the republics gradually introduced new broadcasting technology and built production facilities, and in the period before national television programmes were fully established, the TV broadcasters of the republics retransmitted the news produced by Serbian Television (TV Belgrade) in Serbo-Croatian, as the common language of Croats, Montenegrins and Serbs was then called.

4When I entered the field of media studies as a young researcher, my international experience was modest, yet very inspiring. As an undergraduate, I had an opportunity to listen to lectures by foreign visiting professors, including Dallas Smythe, and I assisted Professor Alex Edelstein in conducting surveys on interpersonal communication and decision-making in Ljubljana. Soon after I started to work for the University of Ljubljana in July 1971, I participated in an international summer school on international journalism on the Croatian island of Dugi otok in the Adriatic Sea, where most of the around 20 participants came from the USA, and one lecturer was Jim Halloran, president of the IAMCR, who had made an important contribution to audience research and the establishment of media studies as a research field. Generally, I can say that I was brought up with a very liberal attitude to ‘bourgeois science’. I developed my critical-Marxist orientation only after completing my master’s degree in 1974, when I started writing my doctoral dissertation on mass communication, human freedom and alienation, defended in 1979 and published in Slovenian in 1981.1

5Following my early liberal experiences in the early 1970s, my first live encounter with an international conference – the 1974 IAMCR conference at Karl Marx University in Leipzig, then German Democratic Republic – in which I participated as an aspiring research assistant with a paper on international radio propaganda, made me quite frustrated. On one hand, I acquired first-hand experience of real ‘ideological imbalances’ as I listened to the ideologically orchestrated presentations and discussions of the Eastern European and Russian participants. Still, it was releasing to listen to prominent critical scholars like Dallas Smythe and Herb Schiller in an open-stage dialogue criticising representatives of conservative/administrative empirical research represented by Elisabeth Noelle Neumann. 2 This was undoubtedly a turning point in my research career, later most clearly expressed in my doctoral dissertation.

6While my early research was largely empirically based, interest in theoretical conceptualisations later prevailed, although I always remained in close contact with methodology and empirical research. In fact, in socialism there was a natural alliance between empirical and critical research, as opposed to capitalism where empirical research is more often associated with administrative research. In what follows, I look back at 20 years of communication research in Yugoslavia, in which I was directly involved, to present selected findings that shed light on the controversies surrounding media development in socialist Yugoslavia. After briefly discussing the beginnings of media and communication research in Yugoslavia and Slovenia, I review research projects on foreign propaganda against Yugoslavia, news gathering and selection in both RTV Ljubljana and Tanjug, and intercultural information and communication flows in Yugoslavia, which I carried out in the 1970s and 1980s.

2. The Pitfalls of Media Research in Socialist Yugoslavia

1While the development of society in most areas from the economy to education was dominated by socialist ideas and regulated by the Communist Party (renamed the League of Communists in 1952), media research that began in the 1960s has only exceptionally been under such a strong influence. The development of the new discipline or field of media and communication research in Yugoslavia was largely marked by “productive inclusivism” or eclecticism, a kind of ‘cohabitation’ of different communication schools and theoretical paradigms that had contributed to its definition, development and institutionalisation at universities. This was primarily due to the absence of original ‘Marxist thought’ in (mass) communication theories on which the discipline’s development could have been based or subordinated to, thereby making the new discipline significantly different from many other disciplines like sociology, in which such a ‘gold standard’ existed. In its early beginnings in Yugoslavia, for example, sociology was often labelled a bourgeois science by the League of Communists’ ideological authorities. To counter this view (with potentially dangerous consequences) and to prove sociology's progressive or Marxist character, sociological authors regularly cited Marx’s works. As reported by Milić, out of 20 classical sociological theorists, including Durkheim, Habermas, Lorenz, Mills, Parsons, Sorokin and Weber, 30% of all citations in Yugoslav sociological articles between 1966 and 1985 referred to Marx. 3 In contrast, in a similar analysis of articles on media and communications published in Yugoslav scientific journals between 1965 and 1986, just 4.6% of citations referred to Marx, even though he still stood out as the most cited author. 4 Contrary to sociology, it would be difficult to argue that Marx(ist) theory – despite the significance of Marx’s early debates on freedom of the press and his later writings on ideology and political economy – could prevail over all other contributions to the field of communication, and thus become the main or even only theoretical foundation for the new discipline's definition, development and academic institutionalisation.

2Like other socialist countries of the twentieth century, political bureaucracies in Slovenia and Yugoslavia were particularly suspicious of empirical research. From the very beginning and for a long time, sociology was seen as a ‘bourgeois science’ and restrictively integrated into academic life, as opposed to the ideologically preferred political sciences. Later, this anti-Marxist ‘class character’ was especially attributed to its empirical – considered administrative – research, notably surveys. Yet, in fact, empirical research in the former socialist societies often acted as a critical impulse against ideologised abstract social sciences, against formalism and simplified generalisations, and was aimed at investigating differences in interests and social contradictions in the processes of socialism's development.

3It should thus come as no surprise that not only books but also the vast majority of communication-related journal articles published in this period were not the result of empirical research. Between 1964 and 1986, just 18.7% of 311 articles related to (mass) communication, as published by 181 authors in 32 Yugoslav social science journals, had an empirical character, a further 7.7% were both theoretical and empirical, yet only 7.1% of them included statistical data analysis.5 The first media-related empirical studies in Yugoslavia were published as late as in 1969, and dominated the scene during the short period of democratisation until 1974 (particularly reporting social survey and audience research results), but after 1975 they almost disappeared for some time.

4During socialism in Yugoslavia, theoretical, often intuitive-speculative approaches combined with normative idealism generally dominated in the scholarly books and journal articles on communications. The prevalence of an intuitive/speculative approach over robust theoretical approaches was reflected in the fact that of all 311 articles included in a 23-year analysis between 1964 and 1986, a mere 2.9% comprised a critical assessment of the theory applied or elaborated on. In total, almost 57% of the citations referred to original publications (44.5%) or translations (12%) in Yugoslav languages. The most often cited media and communication scholars in this period were members of diverse schools of thought, such as Critical Theory (Adorno, Habermas, Enzensberger, Bourdieu), Functionalism (Katz, Lasswell, Lazarsfeld, Merton, Schramm, Riley) and “productive inclusivism” (McLuhan, McQuail, Kayser, Cazeneuve, Weiss). Despite bureaucratic pressures, a kind of ‘cohabitation’ of communication paradigms existed, although they were not equally widespread.

5Nevertheless, the authors most frequently referred to were ‘classical Marxists’ (Marx, Engels, Lenin) and top Yugoslav politicians (Tito, Kardelj, Šetinc, Vlahović). Particularly in the late 1970s, citations reflecting the ‘arguments’ of authorities dominated: in addition to Marx, Edvard Kardelj, the leading Yugoslav party ideologue, was the most often cited author during this period, partly ‘explaining’ the absence of ‘the critical’ in theoretical essays. Papers referring to Marx and Critical Theory could hardly be seen as a systematic “critique of bourgeois mass communication research”, as conceptualised, for example, by Lothar Bisky in the German Democratic Republic.6 Citations of Marxist authors gave no evidence of intellectual commitment to their works. They were often quoted more to ‘legitimise’ their political correctness than substantiating the theoretical relevance of a particular contribution.

6A similar pattern emerged in the organisation of scientific conferences, with reference to the League of Communists' documents and doctrines serving as proof of the social legitimacy (and political correctness) of research. For instance, at the Yugoslav Conference on Inter-Republican Communication held in April 1975, in his opening presentation Firdus Džinić discussed the “ideological basis of inter-republican communication in the documents of the 10 th congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia”.7 Džinić emphasised that the Yugoslav information system should be built according to the attitudes approved by the 10th Congress of the Yugoslav League of Communists and on a unified ideological basis as an integral part of the socialist, self-governing socio-political system. It was supposed to enable the ‘free flow’ of information between individual parts of Yugoslavia, which would practically mean that no “closed communication areas” would exist.8 Following this obligatory reference to party ideology, the conference was conducted according to routine scientific standards. Despite the widespread belief in the West at the time that research findings were questionable because of Marxist influence and “an ideological imbalance toward the left because of the political orientation” of Yugoslavia,9 this could not be proven in empirical research. On the contrary, and not always without reason, bureaucratic party critics pointed to the “positivist and functionalist methods” used in empirical research, along with “revisionist theories”, “technocratic liberalism”, and “abstract humanism”. Western concerns with “ideological imbalances toward the left”, whatever that may have meant, were especially absurd in light of the administrative measures taken against the social sciences in several Yugoslav republics. The official ideological critique also endangered the university programme for journalism in Ljubljana, as it was said to be impregnated with “positivism and bourgeois theories”. The Director of the Yugoslav Institute of Journalism in Belgrade wrote a letter to Slovenian authorities “denouncing Vreg’s communication theory as non-Marxist and proposing that Slovenian journalists should be trained in Belgrade”. 10 As I recall, he also denounced the UNESCO-funded study of foreign radio propaganda in Yugoslavia11 conducted by the Faculty of Sociology, Political Science and Journalism at that time as being a threat to national security.

3. News Gatekeeping Studies and the Role of the Tanjug News Agency

1Notwithstanding ideological and political obstacles, empirical research into the media in Yugoslavia had advanced considerably since the late 1960s. I first encountered empirical media research while completing my journalism studies in the early 1970s as an associate in the Programme Studies Department (PSD) at the Slovenian national public broadcaster Radio-Television Ljubljana. Lado Pohar, a former journalist and correspondent from the USA, the first head of Television Ljubljana, who was the initiator and first leader of the PSD and conducted some audience research with external collaborators even before the department was formally established, held a very ambitious vison of the newly established research department: “Our goal is to help the institute achieve even greater openness in communicating with the audience, and to enable the audience to have an even more important impact on the programme. At the same time, we want to complement if not replace the intuition in the daily programming and directing the development of the policy of both media in our country with the findings of communication research and other sciences” 12

2Similar research units performing audience and readers surveys and content analysis of newspapers, radio, and television programmes were also set up by public broadcast corporations and major newspapers in other Yugoslav republics.13 Yet, following the initial orientation of these departments to enhance the quality of programmes, their operations were more strongly focused on supporting advertising or were discontinued altogether, as occurred with the PSD in Ljubljana.

3Although the research department at Radio and Television Ljubljana mostly administered surveys on listening to and watching radio and television programmes, it also completed more sophisticated empirical research.14 In 1973, I designed a gatekeeping study that analysed 9,102 news items received by Ljubljana radio and television news programmes from news agencies, Yugoslav RTV centres, journalists, and correspondents in the 2 weeks between 24 September and 7 October. Following editorial decisions, 3,597 news items (39.5%) were broadcast on radio and television news programmes. No significant differences between radio and television news were found in the editorial decision-making criteria, albeit almost twice as much news was used in the radio newsroom (50.3% acceptance rate) than for the television programme (28.5%). In a historical perspective, analysis of a selection of news in retrospect reveals interesting peculiarities in the news values held by the Slovenian (broadcast) media in the 1970s.

4In particular, the analysis shows quantitatively balanced reporting on the three world political blocs of the time – the Western and Eastern blocs and the “Third World” or non-aligned countries. While news input was strongly dominated by reporting on the Western bloc, editorial selection sought to reduce this dominance. Second, and not surprisingly, military conflicts were privileged, followed by international relations, while reporting was the most selective when covering science and culture. I would venture to argue that the priorities today are hardly different. Third, the selection of news in RTV Ljubljana was typically related to sources. At that time, Tanjug also sent its customers a selection of news bulletins of major world press agencies (AFP, AP, UPI, TASS, Reuters) as part of its regularly daily service (representing 30% of the total news supply), which was the only official source for the media, even though they also unofficially observed some foreign agencies. The news selection clearly revealed preferences for AFP, which was a major news source for news from third world countries (60.8% of news items used), followed by Reuters (42.6%), TASS (39.8%), AP (36.9%) and UPI (27.6%). The frequency of selecting news reported by Tanjug's own correspondents was slightly below average (36%). Tanjug was, of course, the most common source of news from Yugoslavia, which relates to another feature of news selection at the time. The news release rate was the lowest in reporting on events from Yugoslavia (compared to Western, Eastern and Third-World “blocs”) and the highest with respect to Slovenia: there was a 1.6-times higher probability that news from Slovenia would be selected than news from elsewhere in Yugoslavia. The growing tendency of a relatively weak flow of news and media content within Yugoslavia and people's only slight interest in events in other Yugoslav republics during the 1970s and 1980s was also shown by other analyses and surveys, as discussed later.

| Input structure | Output structure | Acceptance rate | |

| International relations | 43.3 | 50.6 | 46.1 |

| Armed conflicts | 5.3 | 8.5 | 64.0 |

| Internal politics & economics | 25.4 | 25.0 | 38.9 |

| Culture & science | 8.2 | 5.4 | 26.3 |

| Crime, accidents | 2.5 | 1.7 | 28.2 |

| Other | 15.0 | 10.0 | 23.1 |

| Total news items = 100% | 9,102 | 3,597 | 39.5 |

| West | 39.3 | 39.8 | 40.0 |

| East | 20.9 | 23.9 | 45.2 |

| Third World | 25.9 | 29.7 | 45.4 |

| Yugoslavia | 44.2 | 39.8 | 35.5 |

| Slovenia | 13.0 | 18.6 | 56.5 |

| TOTAL | 143.4* | 151.8* | 39.5 |

Source: Slavko Splichal, Pretok sporočil na radiu in televiziji. Bilten SŠP, No. 17 (Ljubljana: RTV Ljubljana, Služba za študij programa, 1976).

5Immediately after completing the gatekeeping study at RTV Ljubljana, I had an opportunity to design a new study focused on foreign news selection criteria at Tanjug's headquarters. A research project on the Yugoslav news agency Tanjug and the Non-Aligned News Agencies Pool (NANAP, established in 1975) was funded by UNESCO as part of its international communication research programme. Already at the outset, the project drew ideological attacks from Belgrade in particular, claiming the research team was providing (ideological) adversaries with confidential information about the work of both Tanjug and other non-aligned news agencies. Although the criticism was disguised as ideological, it was in fact more an expression of envy regarding the new research group in Ljubljana, which was a threat to the monopoly held by the Belgrade-based Yugoslav Institute of Journalism (JIN) in the area of international cooperation, especially as concerns Tanjug and the non-aligned news pool.

6As the leading agency in the pool, Tanjug became a world-renowned news agency at the time. Its national news services aimed at the Yugoslav media and other (generally political) subscribers relied on three main types of sources in foreign news coverage. In September 1977, the average input in Tanjug totalled 3,102 foreign news items per day, of which Tanjug selected 327 or 10.5% for its Yugoslav subscribers. Accounting for 52% of all foreign news delivered, the most important suppliers were the five big international news agencies, AFP, Reuters, TASS, AP and UPI. Tanjug’s own staff of foreign correspondents, numbering 46 by the autumn of 1977, provided 8.3% of the news inflow, while the remaining 34.5% came from 70 national news agencies with which Tanjug was cooperating under a contract.

7In 1963, AP, Reuters, AFP and TASS (UPI did not then exist) supplied Tanjug with over 70% of all news, 5.5% was sent by Tanjug’s own correspondents, 2% was taken from foreign newspapers and radio stations, and the remaining 20% came from all other national agencies. After then, the relative share held by the four major news agencies in Tanjug's structure of incoming foreign news was steadily declining (by almost one-third in 15 years), yet rising in absolute terms. At the same time, the share of national, especially non-aligned, agencies in Tanjug’s news services almost doubled, notably after 1975, when the pool of non-aligned news agencies began operating.

8The 1979 gatekeeping study in Tanjug found that universal selection criteria like ethnocentrism, the economic power of actors reported on, personification or crises and conflicts were not implemented by all agencies. The most significant departure from such universal criteria was seen in the reports of Tanjug and the news agencies of the non-aligned countries. Tanjug’s policy and the non-aligned news agencies’ inclusion in the international news exchange held important consequences for the Yugoslav media. An international comparative study of news exchange conducted in 29 countries around the world 15 found that among all 29 countries Yugoslavia and Poland had reported less news from within its own geopolitical sphere than from any other region. While in most countries the focus was on regional events and news breaking in other parts of the world received only secondary attention, Tanjug supplied Yugoslav media with news on events in the global peripheries.

| Region | Sources of Tanjug’s news services | TOTAL | Discarded news | ||||||||

| Reuters | AP | UPI | AFP | TASS | POOL | Tanjug | Others East | Others West | |||

| Western Europe | 33.1 | 29.2 | 34.4 | 35.9 | 19.9 | 7.4 | 23.9 | 14.9 | 38.0 | 25.2 | 89.0 |

| Eastern Europe | 11.1 | 13.6 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 43.4 | 1.9 | 26.8 | 39.1 | 2.5 | 15.3 | 88.6 |

| Arab countries | 14.3 | 14.5 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 9.5 | 41.9 | 15.9 | 6.4 | 19.4 | 19.1 | 89.6 |

| Asia and Australia | 11.9 | 10.0 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 19.3 | 8.0 | 14.7 | 4.5 | 11.1 | 90.3 |

| Africa | 7.6 | 4.3 | 6.5 | 6.0 | 3.4 | 5.8 | 2.4 | 7.2 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 91.1 |

| North America | 10.8 | 17.4 | 19.3 | 13.9 | 12.8 | 6.0 | 9.9 | 5.0 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 90.0 |

| Latin America | 3.5 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 1.5 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 3.8 | 14.9 | 5.6 | 86.0 |

| International organisations | 7.6 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 6.3 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 4.6 | 8.9 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 85.7 |

| N = 100% | 12.8 | 12.3 | 14.2 | 12.7 | 5.3 | 17.1 | 8.3 | 5.9 | 11.5 | 100.0 | 89.0 |

| Discarded news | 91.7 | 91.9 | 92.5 | 94.4 | 96.3 | 90.3 | 46.3 | 98.6 | 98.7 | ||

4. Yugoslavia as a Target of Foreign Radio Propaganda

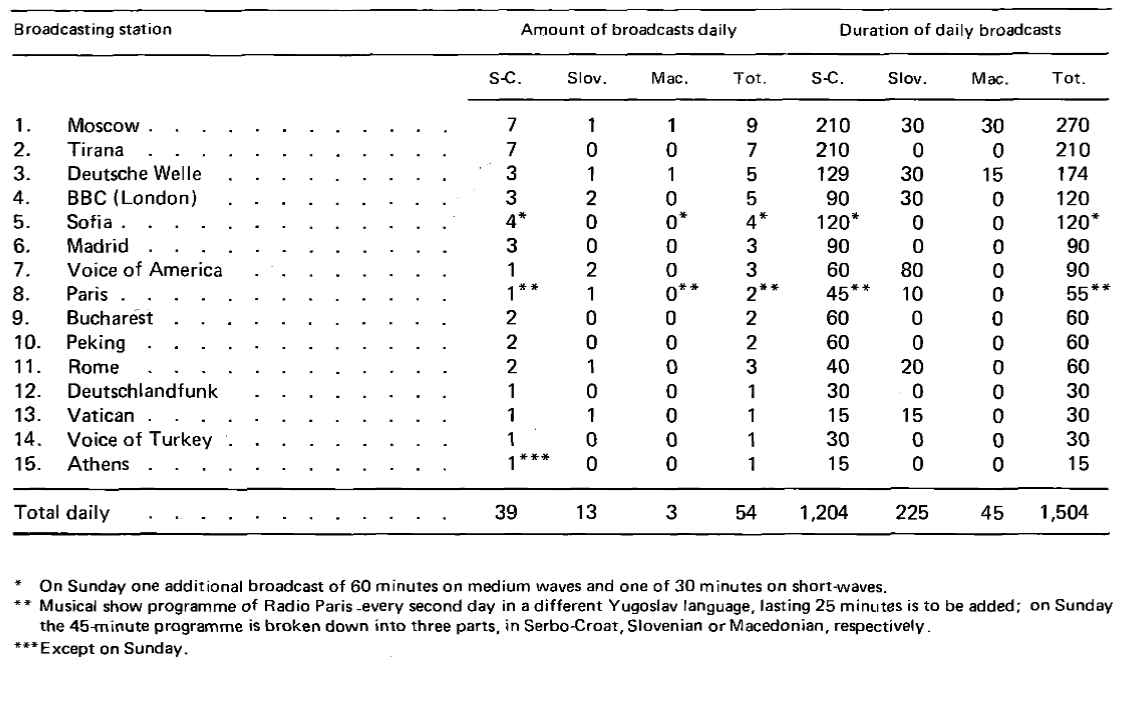

1Despite newer tools of international propaganda emerging in the 1960s and 1970s, international broadcasting more than doubled from 1950 to 1960 and again from 1960 to 1970, reaching a total of over 12,000 hours of external radio programming per week. Throughout its existence, Yugoslavia was high on the agenda of international propaganda due to the armed uprising against the German and Italian occupiers and their allies, the socialist revolution and then the conflict with the Soviet Union, and later because of its leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement. After the Second World War and during the Cold War, radio was the most important medium for international propaganda. All major actors in international politics funded the operation of radio propaganda stations, many of which also broadcast in Yugoslav languages.

2Comparative data on audiences and motives for listening to foreign radio stations in Yugoslavia were not systematically collected while the results of surveys conducted by major propaganda stations in Europe (especially the US Radio Liberty broadcasting from the Federal Republic of Germany, and Deutsche Welle) were of dubious value since they were often used for propaganda purposes. Nevertheless, occasional estimates of the number of listeners reveal the importance of international radio propaganda at the time.

3According to a survey conducted by the Belgrade Institute of Social Sciences on a Yugoslav sample, listening to foreign stations halved between 1965 and 1968, from 27% to 15% of the adult population (yet, it is unclear whether the 1968 figures were collected before or after the invasion of Czechoslovakia). 16 During that time, Voice of America, Radio Moscow, Bucharest and Tirana – each from a different ideological grouping – had the largest audiences in Yugoslavia. More than half the listeners of foreign radio stations stated that they listened to more than one foreign station in order to compare news and commentaries from various sources and thereby create a more objective picture, as the vast majority (90%) of listeners believed that foreign stations only sometimes or never reported objectively.

Source: Tomo Martelanc, Slavko Splichal, Breda Pavlič, Anuška Ferligoj, Vlado Batagelj and Mojca Drčar Murko, External Radio Broadcasting and International Understanding: Broadcasting to Yugoslavia. Reports and papers in mass communication, No. 81 (Paris: UNESCO, 1977), 10.

4A postal survey conducted by Deutsche Welle among its listeners in Slovenia in 1973 showed a relatively large potential impact of radio propaganda programmes because the number of listeners increased greatly during times of crisis. The survey indicated average annual growth of 2%–5% of their listeners in Slovenia (excluding the simultaneous dropout of listeners), but during periods of crisis the level rose to 11%–16% (e.g. during the fall of Ranković in 1965, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, or the Middle East war in 1970). 17 In this light, the decline in listening to foreign radio stations from 41.6% of at least occasional listeners among adult citizens in Slovenia in 1969 to just 19% in 1976 detected by the “Slovenian Public Opinion” survey18 should be taken cum grano salis as it was the first measurement of listening carried out immediately after the Czechoslovak crisis, and the second measurement in a relatively calm political period.

5A critical attitude to the perceived reliability and objectivity of the news not only applied to foreign radio stations, but also the Yugoslav media. In the Slovenian Public Opinion surveys of 1968 and 1972, almost half the respondents agreed that “in our country one must at least sometimes read foreign newspapers, listen to foreign stations or watch foreign television programmes if one wants to be well informed”. The fact that the four most listened to foreign radio stations in Yugoslavia (Voice of America, Moscow, Bucharest, Tirana) came from different ideological clusters suggests that listening to foreign propaganda stations was motivated by the need to compare news and commentary from different sources and not just by general distrust of the domestic media.

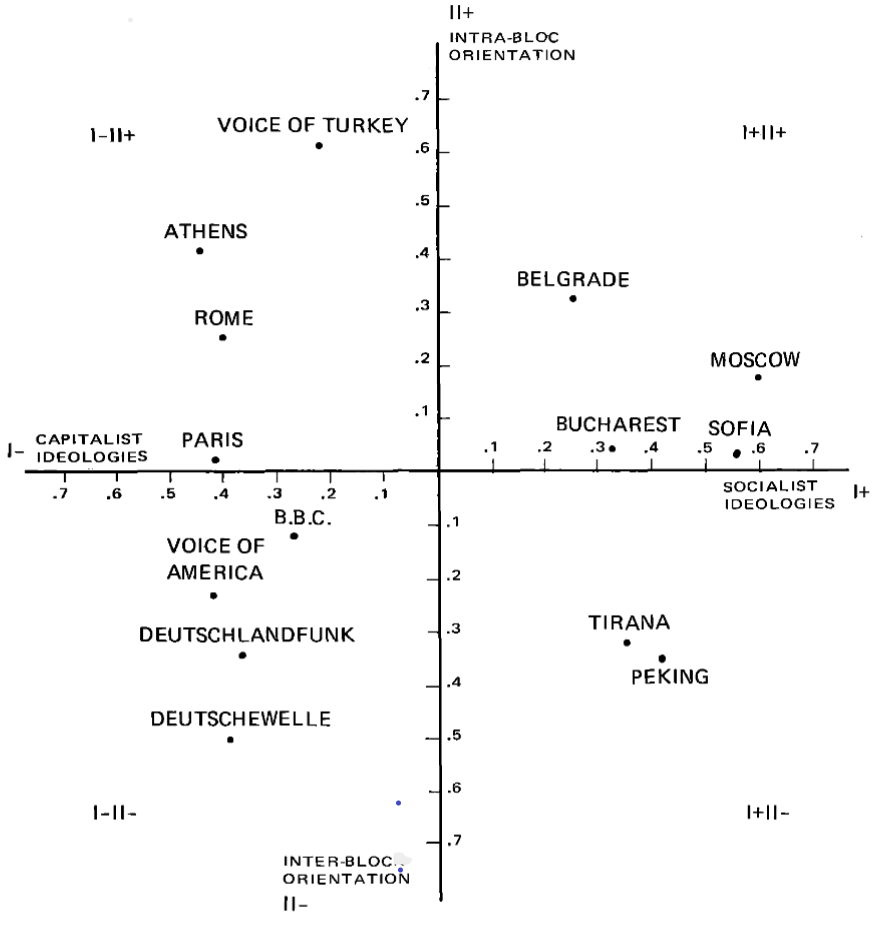

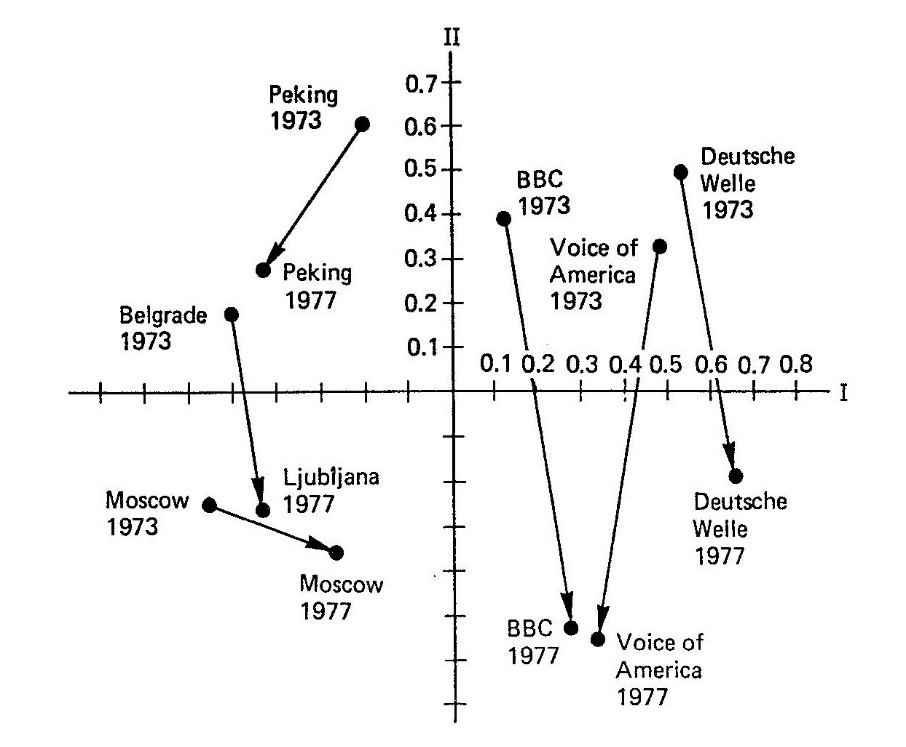

6In this context, an analysis of external radio broadcasting to Yugoslavia was conducted. In 1971, UNESCO adopted an international programme for communication research. Within that programme, research into international communication structures was one of the most important themes. The first 3-year project of this programme (1973–1976) was conducted in Slovenia, and I was in charge of designing research to analyse 15 news programmes of foreign radio stations from 14 countries broadcast in the Yugoslav languages to different national audiences in socialist Yugoslavia, aiming at identifying the common features and differences in radio propaganda.19 The 1-week analysis was repeated in 1997 on a smaller sample of eight foreign broadcasts in Slovene.

7The analysis was focused on symbols as the most significant indicators of ideological systems (re)presented by propaganda, on the evaluation of subjects of international relations (states and international organisations), and distribution of attention to such subjects’ actions. The main feature of the analysed programmes in two different periods was no doubt the consistent and mutually exclusive evaluative (ideological) orientations of various broadcasts. In both periods of the analysis, external radio programmes for Yugoslavia were clustered using different multivariate methods into two exclusive groups: those of the western versus those of the eastern hemisphere. The temporal changes only concerned differences in the distribution of attention, i.e. the fact that the activity of several subjects in international relations, except of the superpowers, varied between different periods.

Source: Martelanc et al., External Radio Broadcasting, 20.

Source: Slavko Splichal and Anuška Ferligoj, “Ideology in International Propaganda,” in: Sociometric Research: Data Collection and Scaling, eds. Willem E. Saris and Irmtraud N. Gallhofer (Houndmills: Macmillan Press, 1988), 69–89.

8The findings of the analysis confirm the significance of propaganda’s ideological dimension, i.e. its subordination to the ruling political and economic interests. This dimension stood out in the sample of radio propaganda stations in each single period as well as cross-time analysis as the factor with the largest explanatory power in factor analysis and the most important discriminatory dimension between clusters obtained by hierarchical agglomerative and local optimisation procedures. The results not only indicated a competitive but an exclusive relationship between the orientations of the capitalist and socialist-oriented groups of propaganda stations. The ideological dimension, while dominant in the programmes of all stations analysed, was more typically discriminatory within the cluster of eastern stations than within the cluster of western ones.

9While none of the analysed stations paid much (or any) attention to the events in Yugoslavia, 20 they all clearly supplemented the Yugoslav media in terms of their potential (dis)socialising impact on Yugoslav audiences. Foreign programmes aimed at Yugoslav listeners reported on generally the same events as the Yugoslav media did (represented in the sample by the External Service of Radio Belgrade and Radio Ljubljana), without providing any deeper knowledge, yet evaluating them differently and associating them with different values. The distribution of attention to international events and associated actors changed considerably over 4 years (1973–1977), but did not differ significantly between eastern and western stations. Nevertheless, western stations (BBC, Voice of America, Deutsche Welle) were more sensitive to changes over time; their programmes were more focused on current events than on major symbolic or ideological themes that were at the forefront of eastern radio stations (Beijing, Moscow). In contrast, the evaluative/ideological orientations were relatively constant over time in all programmes and varied significantly between the western and eastern stations, thus promoting relatively stable agenda-setting profiles over time. As radio stations sought to convince listeners of what were the most important issues from their particular ideological point of view, the dominant actors and values did not change much over time. This led to relatively stable structural relationships between the radio programmes: while they changed slightly between the two analysed periods, their variability did not have a significant effect on the differences between the programmes.

10The characteristics of the content of individual foreign radio programmes and specific ideological clusters of radio stations differed significantly from the characteristics of the Yugoslav stations (Belgrade and Ljubljana) in each period, thus showing a certain incongruence with the prevalent Yugoslav ideology and potential dissocialising effects upon Yugoslav listeners. The dissonance between the content of the foreign radio broadcasts and the Yugoslav media clearly had potentially negative effects on the target communication system. Potentially negative effects increase along with the increase in development level of the transmitting and receiving communication system. The relatively high level of development and openness of the Yugoslav communication system meant that this problem did not reach critical proportions in Yugoslavia. Still, the consequences could be significantly more serious for less developed countries, which was the main reason for the initiative for non-aligned countries to collaborate in the communication field and on the creation of a new global information and communication order in the 1970s.

5. Intercultural Communication in Yugoslavia

1While Yugoslavia had taken decisive action to improve the imbalanced flow of news from around the world, it failed to effectively address the same problem at home. Yugoslavia was not only very different in many respects, including different religions, languages and alphabets, but was also very differently developed economically. Among other things, Yugoslavia was characterised by an “unbalanced flow of news” between the six republics and two autonomous provinces, a problem resembling the challenge that the Yugoslav state, together with the Non-Aligned Movement, sought to address by establishing a pool of non-aligned news agencies. Like the fields of culture, art, education, science and, in part, sports, the media was the domain of republican policies and regulations. Following amendments to the Federal Constitution of 1971, regulation of the media was transferred to the individual republics’ legislation such that the federation only remained responsible for regulating international communication and criminal law for communication offences. After many years of discussions, the Federal Law on the Foundations of the Public Information System was adopted in 1985, intended to bring about greater unity in the normative regulation of relations in the communications sphere. The new law established the basic principles of “public information” in Yugoslavia, the fundamental rights, obligations and responsibilities of the media, its founders and sources of information, and ways of pursuing “special social interests” in the media, while the creation and operation of media organisations remained the republics' exclusive responsibility. Internal political and economic decentralisation ran parallel to the country’s opening up to the outside world in the 1970s. 21

2Considerable differences existed between the communication systems of republics and provinces in terms of media production and consumption, occasionally leading to competition and even conflicts, e.g. over the development of television. Interethnic communication and dissemination of information were supposed to play an important role in eliminating ethnic stratification in Yugoslavia by transforming vertical differences between nations and nationalities into horizontal differences between them and developing cultural pluralism. However, these efforts remained largely normative.

3In 1984, more than 3,000 newspapers (including 27 dailies) and over 1,500 journals with a total yearly circulation of 1,434 million copies were published in Yugoslavia. More than two-thirds of them, with over 80% of the total Yugoslav circulation, were published in Serbo-Croatian, the official language in four of the six Yugoslav republics. The most important publishing centres were in Belgrade (Serbia) and Zagreb (Croatia). Croatian and, particularly, Serbian newspapers were largely dispatched to the other republics, yet no Yugoslav newspaper covered the whole federation. The relative circulation of daily newspapers on average was 95 copies per 1,000 inhabitants, but varied considerably among individual republics.

4Radio and television broadcasting represented a further pluralistic dimension of the Yugoslav communication system(s). In 1984, 202 radio stations produced over 418,000 hours of programming for about 5 million subscribers. One-third of all radio broadcasting was transmitted by 8 central radio stations (1 in each republic and autonomous province), 14% by regional and 5.3% by local radio stations. While the central stations were founded by republican socialist alliances, regional and, especially, local stations were also created by groups in civil society like national minorities, students and cultural organisations.

5Nine television stations transmitted 15 programmes, totalling over 50,000 hours per year, to about 4 million Yugoslav households possessing TV sets in 1984. The number of households with TV sets varied from nearly 80% in the more developed parts of the federation (Slovenia, Croatia, Vojvodina) to less than 50% in Montenegro and Kosovo. Four TV stations broadcast their programmes in Serbo-Croatian (Belgrade, Zagreb, Sarajevo, Titograd), and one each in Slovenian (Ljubljana) and Macedonian (Skopje). TV Koper broadcast programmes in Italian intended for the Italian minorities in Slovenia and Croatia, but also viewed in Italy. Programmes of Television Pristina and Television Novi Sad were broadcast in several languages reflecting the population’s multinational structure (Albanian, Roma and Turkish in Kosovo, and Hungarian, Romanian, Slovak and Ruthenic in Vojvodina).

6The local production of television stations did not exceed one-quarter of the total programming time, while the Yugoslav production combined accounted for two-thirds of the total programming time, with the remaining time being filled by foreign broadcasts. Audiences only had a limited choice in watching television broadcasts that could only be received within the republic of one’s origin and in parts of the neighbouring republics. Still, access to all programmes would not have meant any considerable changes as the programmes were largely the same. In 1987, only 20 cable systems existed in Yugoslavia with no more than 50,000 home terminals, all exclusively being distribution systems without local programming in the local head-ends. In the 1980s, own television production gradually increased, while production from other republics began to be replaced by imported Western programmes, chiefly the United States and the United Kingdom (see Table 4).

| 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | |

| Total programming (in thousand minutes) | 356 | 388 | 383 | 404 | 417 |

| Own programming, in % | 22 | 28 | 31 | 35 | 38 |

| - % of repeats | 27 | 34 | 35 | 34 | 36 |

| Other Yugoslav TV, in % | 46 | 39 | 37 | 28 | 22 |

| - % of repeats | 22 | 19 | 14 | 13 | 9 |

| Foreign-made, in % | 32 | 33 | 32 | 37 | 40 |

| - % of repeats | 21 | 22 | 25 | 24 | 19 |

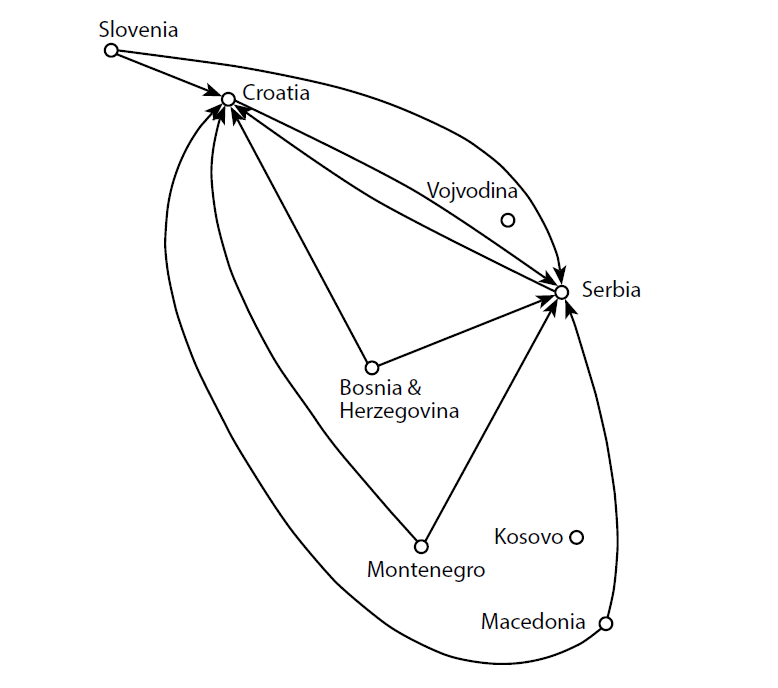

7Asymmetric relations among the republics became ever more apparent in both media reporting and the exchange of television programmes, and were also reflected in mutual (dis)information among citizens of different republics. There was a relatively weak interethnic flow of economic, political and cultural information between parts of Yugoslavia. A large share of the population was not informed about past and current factors and events important for understanding the situation and development of the other Yugoslav nations and nationalities. The nations about which most information was available in Yugoslavia were the biggest ones, i.e. Serbs and Croats, while the smaller nations were, on average, significantly less visible in the media of other republics.

8According to a 1980 Yugoslav survey, the history of other nations arouses the greatest interest of citizens in all republics and both provinces (26.3% of respondents on average, from 20.0% in Macedonia to 36.6% in Kosovo), followed by the economy (18.8%), political events (15.5%), culture and the arts (14.8%), sports (11.0%) and entertainment (8.2%). Interest in economic information was significantly stronger among citizens from the most developed republics (Slovenia and Croatia), but also in the least developed province of Kosovo.22 In addition to the citizens of Montenegro and Serbia, political news was given priority by respondents in Montenegro, Serbia and Kosovo. Despite the lack of knowledge about other republics and provinces, in the late 1970s almost 50% of respondents in the whole of Yugoslavia believed the amount of information in the national media covering other republics and provinces was adequate and only one-tenth of them were very disappointed with the amount of intercultural news in the media. Only one-fifth of the Yugoslav population knew all eight central national dailies: 79.5% knew Politika, published in Serbia, 70.0% Vjesnik (Croatia), 48.1% Rilindja (Kosovo; perhaps also because of the paper's non-Slavic title without really knowing it), 46.7% Delo (Slovenia), 43.0% Oslobodjenje (Bosnia and Herzegovina), 31.0% Pobjeda (Montenegro), 26 .4% Večer (Macedonia) and 24.0% Dnevnik (Vojvodina). Similar or less mutual knowledge (or ignorance) also existed about other historical, economic, political and cultural characteristics of individual republics.

9The pattern of information exchange between the republics through print and television media that was discerned in the 1980s could hence be expected. Only the newspapers published in Belgrade and Zagreb successfully crossed each republic’s borders. This was especially true for the sports dailies Sportske novosti (published in Zagreb) and Sport (Belgrade), which in 1984 sold 40% and 38% of their circulation, respectively, in other republics. Five political dailies sold more than 20% of their circulation outside the republics in which they were published: the Croatian Vjesnik and tabloid Večernji list, published in Zagreb, and the Serbian Politika and tabloids Politika ekspres andVečernje novosti, published in Belgrade. The daily newspaper Borba had special editions in Cyrillic and Latin, thus covering the entire Serbo-Croatian language area; most readers were in Serbia (61% of total circulation), followed by Croatia (21%) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (10%). Some magazines had most of their readers in other republics; again, the largest share of circulation sold outside the republic of publication was held by the sports magazine Tempo weekly from Belgrade, with two-thirds of its total circulation sold in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in particular.

10A similar pattern emerged with the exchange of television programmes among the broadcasting centres in the Yugoslav republics. The normatively declared “interconnection and transmission of cultures” through television was often one-way, primarily from the Serbo-Croatian language area to the smaller national and linguistic communities (Macedonian, Slovenian, Albanian). Since this was a period of terrestrial television, television broadcasts made by other republics were not available to watch directly, except in the border regions of the republics. In 11 of 14 programmes, most broadcasts were in the Serbo-Croatian spoken language or were subtitled in Serbo-Croatian. The only exceptions were Channel 1 in Ljubljana (in Slovenian) and Skopje Television (in Macedonian) and the Pristina Television programme (in Albanian; see Table 5). As shown by the arrows in Figure 3, the only important creators of external television programmes were Television Belgrade (Serbia) and Television Zagreb (Croatia), from which all four of the other republics imported over 10% of the programmes they broadcast in 1984, whereas in the opposite direction the programme exchange was close to zero.

| Television station | Total hours | Percent of own production | Percent of programme in | ||||

| Serbo-Croatian | Slovenian | Macedonian | Albanian | Other | |||

| Belgrade 1 | 4,003 | 33 | 95 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Belgrade 2 | 2,617 | 37 | 89 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Ljubljana 1 | 3,415 | 34 | 19 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Ljubljana 2 | 2,299 | 4 | 83 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Novi Sad | 2,1185 | 47 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 47 |

| Prishtina | 3,092 | 48 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 71 | 23 |

| Sarajevo 1 | 3,724 | 19 | 96 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Sarajevo 2 | 2,116 | 15 | 88 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Skopje 1 | 3,971 | 31 | 38 | 0 | 55 | 3 | 4 |

| Skopje 2 | 2,417 | 15 | 62 | 1 | 33 | 1 | 3 |

| Titograd 1 | 3,836 | 9 | 96 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Titograd 2 | 2,529 | 2 | 88 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Zagreb 1 | 3,564 | 36 | 95 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Zagreb 2 | 2,152 | 25 | 91 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

Source: Splichal in Vreg, Množično komuniciranje, 105.

6. Conclusion

1In retrospect, the conclusion seems obvious: socialist Yugoslavia’s efforts to democratise its international and intercultural communication were ambitious and partly successful in the short term, but ultimately failed – as did the Socialist Yugoslavia project itself. The results of research looking at the characteristics of external radio broadcasting, news selection and newspaper and television traffic in Yugoslavia during the 1970s and 1980s show that asymmetry, bias, imbalance, and one-way traffic strongly marked both the external (international) and internal (intercultural) communication of Yugoslavia. Of course, the results of this research are more illustrative than a systematic explanation of the internal and external communication processes in Yugoslavia.

2In 1986, I concluded my essay in Mass Communication and the Development of Democracy by arguing, “Despite the many contradictions with the establishment of social ownership and the development of self-management in the field of mass communication, the potential of Yugoslav society is far from being exploited”.23

3Even 35 years later, I find this assessment to be very accurate. Let me illustrate this in three points.

4In the light of contemporary debates on the autonomy of public service media in Slovenia and elsewhere across Europe (and beyond), I recall my dispute over the draft law on public information in 1985.24 At that time, I was critical of the lack of powers that media councils possessed under the (new) law, yet today I can say that media councils were more democratically designed in the 1980s than, for example, today’s RTV Slovenia Programme Council (under the 2005 law). These councils, as key social governing bodies in the media, were made up of delegates of employees of communication organisations and delegates of users in the proportion determined by the founding act. It was essential, however, that the delegates be appointed directly by the relevant organisations and communities defined in the founding act, without the interference of the founder, who was typically the Socialist Alliance of Working People. One of my biggest criticisms 25 was that the editor-in-chief was not appointed by the council but directly by the founder. Still, compared to the current ‘democratic’ regime dominated by (ruling) political parties directly and indirectly represented in the Programme Council of Radio and Television Slovenia, the councils in the 1980s enjoyed greater political autonomy. According to modern standards of public service media autonomy, this remains the most appropriate path to follow to ensure their autonomy.

5In the international comparative analysis of media reporting conducted in 1984 mentioned earlier, Slovenian newspapers proved to be the most internationally-oriented among other media in 29 countries. The considerable attention paid to international events outside the world’s centres was largely due to Yugoslavia’s foreign policy of non-alignment. Tanjug, with its extensive correspondent network and cooperation with the press agencies of non-aligned countries, provided the Yugoslav media with news about events that had attracted the attention of peripheral areas. In general, at that time, daily newspapers and radio and television news programmes devoted more space, time and resources, including their own correspondents, to international news than they do today, which also had a significant impact on people’s international orientation. Such media policy was principally in line with the ideas of a new world information and communication order (NWICO) 26 reaffirmed today in discussions on global Internet governance, but was abandoned after Slovenia’s independence, transition to capitalism, and growing nationalism.

6On the other hand, ethnocentric interests prevailed in the intercultural communication in Yugoslavia even before the federation’s final disintegration. Mutual interest among the republics was quite low, limited in the media to protocol political news, which correlated with people in individual republics' general disinterest in news from other republics and ethnic groups with a different linguistic, religious and cultural heritage. The news values proclaimed and applied to the international flow of news were not applied in intercultural communication within Yugoslavia. What Schöpflin described as “a semi-authoritarian system by consent” that is supposed to characterise all post-communist systems, which were “democratic in form and nationalist in content”27 and consisted of “an evident element of consent for semi-democratic practices” and “legitimated either by nationalism or by etatism, or by a subtle combination of the two”, already emerged in late socialist or pre-capitalist Yugoslavia. Ethnonationalism first erupted in Yugoslavia in the early 1970s and was never really curbed later. Ethnocentric news media contributed to the rising political and economic nationalisms that eventually shattered the country to pieces. They may have missed the opportunity to contribute to a rationally guided separation, as occurred in Czechoslovakia, which was founded in the same year as the first Yugoslavia (1918) and peacefully dissolved in 1993, 2 years after Slovenia and Croatia declared independence.

7In my 1994 book Media Beyond Socialism, I challenged the view that the burial of authoritarian practices in socialist countries had been followed by a smooth transition to democracy. Instead, I argued that the post-communist media had mimicked Western economic and political practices and was often exposed to the negative influences of authoritarianism, commercialism and nationalism. Many countries have suffered enormously not only from a lack of civic participation and control, but also from the erosion of the indigenous intellectual foundations of social transformation that were lost after the sudden takeover of political and economic power. Although political changes have significantly broadened the horizons of human freedom, today I unfortunately conclude that not only was my assessment of the new threats quite accurate at the time, but the situation in several countries, including Slovenia, has even worsened following the rise of authoritarian governments.

Sources and Literature

- Bisky, Lothar. Zur Kritik der bürgerlichen Massenkommunikationsforschung. Berlin, DDR: VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1974.

- Džinič, Firdus and Ljiljana Bačević. Inostrana propaganda u Jugoslaviji. Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka, 1958.

- Foreign News in the Media: International Reporting in 29 Countries, Reports and papers on mass communication, No. 93. Paris: UNESCO, 1985.

- Klinar, Peter, Slavko Splichal and Niko Toš. Informiranost o republikama i pokrajinama, narodima i narodnostima. Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka, 1980.

- Kostanjšek, Breda. Izveštaj o emitovanom televizijskom programu u 1989. godini. Interno gradivo. Ljubljana: RTV Slovenija, 1990.

- MacBride Report. Communication and Society Today and Tomorrow: Many Voices One World. Towards a New More Just and More Efficient World Information and Communication Order. Paris: Unesco, 1980.

- Milić, Vojin. “Primena nekih bibliometrijskih i prosopografskih postupaka u proučavanju istorije sociologije.” Sociološki pregled 12, No. 1-2 (1988): 73–98.

- Martelanc, Tomo. “Jugoslovansko posvetovanje o medrepubliškem komuniciranju.” Teorija in praksa 12, No. 4-5 (1975): 527–30.

- Martelanc, Tomo, Slavko Splichal, Breda Pavlič, Anuška Ferligoj, Vlado Batagelj and Mojca Drčar Murko. External Radio Broadcasting and International Understanding: Broadcasting to Yugoslavia. Reports and papers in mass communication, No. 81. Paris: UNESCO, 1977.

- Pohar, Lado. Problematika Službe za študij programa (mimeo). Ljubljana: Služba za študij programa, RTV Ljubljana, 1975.

- Pohar, Lado and Tilka Jamnik. Bibliografija raziskav radia in televizije, opravljenih v raziskovalnih centrih jugoslovanskih RTV ustanov v letih 1952–1977, Bilten SŠP, No. 7. Ljubljana: Služba za študij programa, RTV Ljubljana, 1978.

- Schöpflin, George. “Post-Communism: A Profile.” Javnost-The Public 2, No. 1, (1995): 63–73.

- Smith, Stanley. “Mass Media and International Understanding by France Vreg.” In: International and Intercultural Communication Annual, Vol. 6. Ed. Nemi C. Jain, 116–19. Annandale, Va.: Speech Communication Association, 1982.

- Splichal, Slavko. Socializacijske vsebine na televiziji, Bilten SŠP, No. 8. Ljubljana: Služba za študij programa, RTV Ljubljana, 1974.

- Splichal, Slavko. Pretok sporočil na radiu in televiziji, Bilten SŠP, No. 17. Ljubljana: Služba za študij programa, RTV Ljubljana, 1976.

- Splichal, Slavko. Množično komuniciranje med svobodo in odtujitvijo. Maribor: Obzorja, 1981.

- Splichal, Slavko. “Razsežnosti svobode komuniciranja. Ob osnutku zakona o javnem obveščanju.” Naši razgledi, January 25 and February 8. 1985.

- Splichal, Slavko. Mlini na eter: propaganda, reklama in selekcija sporočil v množičnem komuniciranju. Ljubljana: Partizanska knjiga, 1984.

- Splichal, Slavko. “Self-management and the Media.” In: Censorship and Libel: The Chilling Effect (Studies in Communications, Vol. 4). Ed. Thelma McCormack, 1–20. London: JAI Press, 1990.

- Splichal, Slavko. “Indigenisation vs. Ideologisation: Communication Science on the Periphery.” European Journal of Communication 4, No. 3 (1994): 329–59.

- Splichal, Slavko. Media Beyond Socialism. Boulder: Westview, 1994.

- Splichal, Slavko and Anuška Ferligoj. “Ideology in International Propaganda.” In Sociometric research: Data Collection and Scaling. Eds. Willem E. Saris and Irmtraud N. Gallhofer, 69–89. Houndmills: Macmillan Press, 1988.

- Splichal, Slavko and France Vreg, Množično komuniciranje in razvoj demokracije. Ljubljana: Komunist, 1986.

- Šrot, Vida. “Zgodovina raziskovanja RTV programov in občinstva: Služba za študij programa in njeni nasledniki.” Javnost – The Public 15, supplement (2008):133–50.

- Vreg, France. “Trideset let komunikacijske znanosti na Slovenskem.” Teorija in praksa 28 (1991): 8–9, 1018–24.

Slavko Splichal

PREMISLEK O PRISPEVKIH SOCIALISTIČNE JUGOSLAVIJE K MEDNARODNEMU IN MEDKULTURNEMU KOMUNICIRANJU

POVZETEK

1V tem članku predstavljam (ponovno) branje nekaterih svojih raziskav in razprav o množičnem komuniciranju in razvoju socialistične demokracije v Jugoslaviji, objavljenih v zadnjih dveh desetletjih obstoja večnacionalne federacije pred njenim nenadnim in nasilnim propadom. Članek je zasnovan kot ponovna presoja ključnih idej in rezultatov nekaterih empiričnih raziskav, ki sem jih zasnoval in izvajal v sedemdesetih in osemdesetih letih prejšnjega stoletja do osamosvojitve Slovenije leta 1991. Vključujejo več različnih tematik, kot so komuniciranje med republikami v Jugoslaviji, tuja radijska propaganda in delovanje tiskovne agencije Tanjug, zbiranje novic in redakcijsko odbiranje ter razvoj komunikologije kot znanstvene discipline v Jugoslaviji.

2V mednarodni primerjalni analizi poročanja medijev v 29 državah iz leta 1984 so se slovenski časopisi izkazali za najbolj mednarodno usmerjene. Precej je k pozornosti, ki je bila posvečena mednarodnim dogajanjem izven svetovnih središč, prispevala jugoslovanska zunanja politika neuvrščenosti. Tiskovna agencija Tanjug je s svojo razvejano dopisniško mrežo in sodelovanjem s tiskovnimi agencijami neuvrščenih držav jugoslovanskim medijem posredovala novice o dogodkih, ki so pritegovali pozornost območij zunaj svetovnih političnih in ekonomskih središč. Na splošno so takrat slovenski dnevni časopisi ter radijske in televizijske informativne oddaje mednarodnim novicam namenjali več prostora, časa in sredstev, skupaj z lastnimi dopisniki, kot danes, kar je pomembno vplivalo tudi na mednarodno usmerjenost ljudi. Takšna medijska politika je bila v skladu z idejami o novem svetovnem informacijsko-komunikacijskem redu (NWICO), ki se danes ponovno uveljavljajo v razpravah o globalnem upravljanju interneta, vendar so se ji slovenski mediji po osamosvojitvi Slovenije, prehodu v kapitalizem in z naraščajočim nacionalizmom odrekli.

3Po drugi strani pa so v medkulturnem komuniciranju v Jugoslaviji prevladovali etnocentrični interesi že pred dokončnim razpadom federacije. Vzajemni interes med republikami je bil precej šibek, v medijih je bil omejen na protokolarne politične novice, kar je bilo v korelaciji s splošnim nezanimanjem ljudi v posameznih republikah za novice iz drugih republik in etničnih skupin z drugačno jezikovno, versko in kulturno dediščino. Novičarske vrednote, ki so bile uveljavljene v mednarodnem poročanju, niso prevladovale tudi v medkulturnem komuniciranju znotraj Jugoslavije. Etnonacionalizem je v Jugoslaviji prvič izbruhnil v zgodnjih sedemdesetih letih prejšnjega stoletja in ga pozneje nikoli niso zares zajezili. Etnocentrični mediji so prispevali k naraščajočemu političnemu in gospodarskemu nacionalizmu, ki je sčasoma pripeljal do razpada države. Morda so tudi mediji prispevali k zamujeni priložnosti, da bi omogočili racionalno razpravo in ločitev republik po mirni poti, kot se je to zgodilo na Češkoslovaškem, ki je bila ustanovljena istega leta kot prva Jugoslavija (1918) in mirno razpuščena leta 1993, dve leti po razglasitvi neodvisnosti Slovenije in Hrvaške.

4V začetku devetdesetih let preteklega stoletja sem oporekal prepričanju, da je pokopu avtoritarnih praks v socialističnih državah sledil gladek prehod v demokracijo. Spremembe po letu 1990 so nakazovale, da so postkomunistični mediji posnemali zahodne gospodarske in politične prakse in bili pogosto izpostavljeni negativnim vplivom avtoritarnosti, komercializacije in nacionalizmov. Očitno ni šlo le za demokratični primanjkljaj, odsotnost državljanske udeležbe in nadzora, temveč tudi za erozijo avtohtonih intelektualnih temeljev družbene preobrazbe, ki so se izgubili po nenadnem prevzemu politične in gospodarske oblasti. Čeprav so politične spremembe tistega časa bistveno razširile obzorja človekove svobode, danes žal ugotavljam, da je bila moja takratna ocena novih groženj precej natančna in da so se razmere v marsikateri državi, tudi v Sloveniji, z vzponom avtoritarnih strank celo poslabšale.

* This work was financially supported by the Slovenian Research Agency, contract number J5-1793.

** Professor, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Kardeljeva ploščad 5, SI-1000, Ljubljana; slavko.splichal@fdv.uni-lj.si

1. Slavko Splichal, Množično in javno komuniciranje: od množičnega komuniciranja kot negacije javnega v razvitem kapitalizmu do možnosti za vzpostavitev njune enotnosti v samoupravni socialistični demokraciji: doktorska disertacija (Ljubljana: Fakulteta za sociologijo, politične vede in novinarstvo; S. Splichal, 1979). Slavko Splichal, Množično komuniciranje med svobodo in odtujitvijo (Maribor: Obzorja, 1981).

2. Anteil der Massenmedien bei der Herausbildung des Bewußtseins in der sich wandelnden Welt, Internationale wissenschaftliche Konferenz, IX. Generalversammlung der AIERI, Leipzig (DDR), 17. 9. – 21. 9. 1974, 2 Bde. (Leipzig: Sektion Journalistik, VDJ der DDR, AIERI, 1975).

3. Vojin Milić, “Primena nekih bibliometrijskih i prosopografskih postupaka u proučavanju istorije sociologije,” Sociološki pregled 12, No. 1–2 (1988): 73–98.

4. Slavko Splichal, “Indigenisation vs. Ideologisation: Communication Science on the Periphery,” European Journal of Communication 4, No. 3 (1994): 329–59.

5. Ibidem.

6. Lothar Bisky, Zur Kritik der bürgerlichen Massenkommunikationsforschung (Berlin, DDR: VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1974).

7. Tomo Martelanc, “Jugoslovansko posvetovanje o medrepubliškem komuniciranju,” Teorija in praksa 12, No. 4–5 (1975): 527–30.

8. Ibid., 528.

9. Stanley Smith, “Mass Media and International Understanding by France Vreg,” International and Intercultural Communication Annual, Vol. 6, ed. Nemi C. Jain (Annandale, Va.: Speech Communication Association, 1982), 116–19.

10. France Vreg, “Trideset let komunikacijske znanosti na Slovenskem,” Teorija in praksa 28, No. 8-9 (1991): 1018–24, 1021.

11. Tomo Martelanc, Slavko Splichal, Breda Pavlič, Anuška Ferligoj, Vlado Batagelj and Mojca Drčar Murko, External Radio Broadcasting and International Understanding: Broadcasting to Yugoslavia. Reports and papers in mass communication, No. 81 (Paris: UNESCO, 1977).

12. Vida Šrot, “Zgodovina raziskovanja RTV programov in občinstva: Služba za študij programa in njeni nasledniki,” Javnost – The Public 15, supplement (2008): 133–50, 134. Lado Pohar, Problematika Službe za študij programa (mimeo) (Ljubljana: Služba za študij programa, RTV Ljubljana, 1975).

13. Lado Pohar and Tilka Jamnik, Bibliografija raziskav radia in televizije, opravljenih v raziskovalnih centrih jugoslovanskih RTV ustanov v letih 1952–1977, Bilten SŠP, No. 7 (Ljubljana: Služba za študij programa, RTV Ljubljana, 1978).

14. Slavko Splichal, Socializacijske vsebine na televiziji, Bilten SŠP, No. 8 (Ljubljana: Služba za študij programa, RTV Ljubljana, 1974). Slavko Splichal, Pretok sporočil na radiu in televiziji, Bilten SŠP, No. 17 (Ljubljana: Služba za študij programa, RTV Ljubljana, 1976).

15. Foreign News in the Media: International Reporting in 29 Countries, Reports and Papers on Mass Communication, No. 93 (Paris: UNESCO, 1985).

16. Firdus Džinič and Ljiljana Bačević, Inostrana propaganda u Jugoslaviji (Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka, 1968).

17. Slavko Splichal, Mlini na eter: propaganda, reklama in selekcija sporočil v množičnem komuniciranju (Ljubljana: Partizanska knjiga, 1984).

18. The longitudinal “Slovenian Public Opinion” survey was established in 1968 at the School of Political Sciences in Ljubljana, later transformed into the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Ljubljana.

19. The study was completed in 1977 upon publication of the monograph External Radio Broadcasting and International Understanding: Broadcasting to Yugoslavia in the “UNESCO Reports and papers in mass communication.”

20. The only exception was Radio Madrid in 1973, which had a markedly negative assessment of Yugoslav domestic politics and explicitly supported Yugoslav political emigration.

21. For more details, see e.g. Slavko Splichal and France Vreg, Množično komuniciranje in razvoj demokracije (Ljubljana: Komunist, 1986). Slavko Splichal, “Self-management and the Media,” in: Censorship and Libel: The Chilling Effect (Studies in Communications, Vol. 4), ed. Thelma McCormack (London: JAI Press, 1990), 1–20.

22. Peter Klinar, Slavko Splichal and Niko Toš, Informiranost o republikama i pokrajinama, narodima i narodnostima (Beograd: Institut društvenih nauka, 1980).

23. Slavko Splichal and France Vreg, Množično komuniciranje in razvoj demokracije (Ljubljana: Komunist, 1984), 179.

24. Slavko Splichal, “Razsežnosti svobode komuniciranja. Ob osnutku zakona o javnem obveščanju,” Naši razgledi, 25 January and 8 February 1985.

25. Ibid.

26. Communication and Society Today and Tomorrow: Many Voices One World. Towards a New More Just and More Efficient World Information and Communication Order (MacBride Report) (Paris: UNESCO, 1980).

27. George Schöpflin, “Post-Communism: A Profile,” Javnost-The Public 2, No. 1 (1995): 63-73, 63, 66.