The Portrayal of Africa in the Newspaper Zgodnja Danica from 1849 to 1859

IZVLEČEK

PRIKAZ AFRIKE V ČASOPISU ZGODNJA DANICA MED LETOMA 1849 IN 1859

1Članek se osredotoča na podobo Afrike in Afričanov v časopisu Zgodnja Danica med Slovenci v obdobju od leta 1849 do 1859. V tem času je katoliško misijo za Srednjo Afriko pod vodstvom Ignacija Knobleharja podpiralo tudi avstrijsko cesarstvo zaradi morebitne kolonialne širitve, desetletje pa je sovpadalo z začetkom slovenskega narodotvornega procesa. Po letu 1848 pa so prevladali neabsolutistični sistem in katoliška ideološka načela, tako da sta v slovenščini lahko izhajala le dva časopisa, eden od njiju Zgodnja Danica . Luka Jeran, urednik revije in odločen podpornik misijona, je objavil, prevedel in cenzuriral številna pisma in poročila Knobleharja in njegovih sodelavcev, ki so predstavljala pogled misijonarjev na značilnosti pokrajine in prebivalcev dežel, ki so danes del Egipta, Sudana in Južnega Sudana. Pokrajina je bila predstavljena kot “oddaljena” in z “nezdravim podnebjem”.

2Nasprotno so bili prebivalci na eni strani prikazani kot bistri, lepi in spretni, na drugi strani pa – z zahodnjaške perspektive razvoja in napredka – kot “leni in nerazviti”. Poleg tega so članki, ki so jih napisali ljudje, ki nikoli niso bili v Afriki, ustvarili stereotip “nemočnega in revnega” Afričana, medtem ko je bila dežela prikazana kot “temačna” in “nevarna”. Številne “zbiralne akcije” v podporo srednjeafriški misiji, ki predstavljajo del prevladujoče podobe, razkrivajo ne le, kako so Slovenci videli Afriko in Afričane, temveč tudi, kako so dojemali “sebe” v nasprotju z “drugimi”, pri čemer se je izoblikoval “avtosterotip” Slovencev, ki lahko “pomagajo” tistim, za katere menijo, da potrebujejo njihovo pomoč.

3Ključne besede: Afrika, Afričani, Zgodnja Danica, stereotipi, Drugi

ABSTRACT

1The article focuses on the image of Africa and Africans in the Zgodnja Danicanewspaper among Slovenians in the period from 1849 to 1859. At that time, the Catholic mission for Central Africa under the leadership of Ignacij Knoblehar was also supported by the Austrian Empire for the reasons of a potential colonial expansion, while the decade coincided with the beginning of the Slovenian nation-building process. After 1848, however, the non-absolutist regime and the principles of Catholic ideology prevailed, so that only two newspapers were allowed to be published in Slovenian, one of them Zgodnja Danica. Luka Jeran, the editor of the journal and strong promoter of the mission, published, translated, and censored numerous letters and reports by Knoblehar and his co-workers that presented the missionary’s view of the physical aspects and people of what are now Egypt, Sudan, and South Sudan. The land was portrayed as “distant” and as possessing an “unhealthy climate”.

2In contrast, the people were portrayed, on the one hand, as bright, beautiful, and skilled, while on the other hand, they were deemed as “lazy and undeveloped”, as they were seen from the Western perspective of development and progress. Moreover, the articles written by people who had never been to Africa generated the stereotype of the “helpless and poor” African, while the land was portrayed as “dark” and “dangerous”. As a part of the prevailing image, numerous “fundraisers” in support of the Central African mission reveal not only how Slovenians saw Africa and Africans, but also how they saw “themselves” in contrast to “the others”, forming an “autostereotype” of the Slovenian who can “help” those who, in their perception, needed their assistance.

3Keywords: Africa, Africans, Zgodnja Danica, stereotypes, the Others

1. Introduction

1The history of the (one-way) relations between Slovenians and Africans offers much material that can be interpreted from the viewpoint of the contemporary issues of intercultural dialogue and stereotypes regarding foreign cultures. 1 Precisely in the middle of the 19th century, Slovenians maintained one of the closest connections with the African continent through a Catholic mission led by the missionary Dr Ignacij Knoblehar (1819–1858), born in Škocjan na Dolenjskem, which is a part of today’s Republic of Slovenia (in continuation Slovenia). He was accompanied by fellow missionaries and artisans from Carniola and other parts of the territory that is now Slovenia, 2 as well as from other provinces that are nowadays parts of the Republic of Austria (in continuation Austria). They regularly reported to their homeland in the form of letters published in the Zgodnja Danica newspaper, a Catholic church newspaper published in the Slovenian language and printed in Ljubljana from 1849 to 1902. The decade coincided with Bach’s absolutist era in the Austrian Empire when Zgodnja Danica was one of only two newspapers published in the Slovenian language. Consequently, many Slovenians read Zgodnja Danica, which contained numerous articles based on the direct reports of Slovenians from the area that is nowadays the Arab Republic of Egypt (in continuation Egypt), the Republic of the Sudan (in continuation Sudan), and the Republic of South Sudan (in continuation South Sudan). The present article aims to show how Africa and Africans were presented to Slovenians in the pre-colonial period in the mid-nineteenth century in the missionary and Catholic ideology prevalent at the time. Despite many studies of the missionary Ignacij Knoblehar, in Central Africa, there has been no comprehensive, systematic, and in-depth study of the presentation of Africa in the articles of the Zgodnja Danica newspaper in the decade under consideration. To understand the genesis of the image of Africa among Slovenians, letters, reports, and articles about Africa in Zgodnja Danica from 1849 to 1859 will be examined using content analysis methods, mainly in a qualitatively combined quantitative manner. Moreover, the comparison of texts based on the writers’ direct and indirect experiences in Africa will be a valuable source for investigating the origins of representations, stereotypes, and prejudices about Africa and Africans among Slovenians. In the article, we will first address the historical context of the decade from 1849 to 1859, which is also the era of the beginning of the nation-building process of Slovenians, who were, at the time, a part of the Habsburg Monarchy. We will revisit the Habsburg colonial aspirations and the historical context of the Catholic mission in the area that is nowadays Sudan and South Sudan. The focus of the article will be an analysis of the content of the missionary reports in the Zgodnja Danica magazine. In the second part, we will analyse the texts in Zgodnja Danica, written by authors who never set foot in Africa but wrote about it nevertheless, and about the various activities related to Africa among Slovenians in the decade under consideration.

2. Slovenian Nation-building Process and the Role of National (Auto)Stereotypes

1Vasilij Melik placed the first developments of the Slovenian nation-building process in the 9th century, in the times of Carantania, 3 followed by Primož Trubar and the first book in the Slovenian language in the 15th century. For Melik, the turning point of the Slovenian nation-building process were the times of the national movements in the Habsburg Monarchy, under Maria Theresa and Joseph II’s rule, while Marko Pohlin emphasised the importance of the Slovenian language. 4 Fran Zwitter placed the beginning of the Slovenian nation-building process among the people who were culturally active during the Age of Enlightenment.5 Miroslav Hroch6 dated the onset of national agitation in the Slovenian region to around 1840–1848, to the period of “Metternich’s absolutism”, when the dissatisfied elites in the Slovenian territory started to gain sympathisers for the “national matter” (“za narodno stvar”). Knoblehar’s mission in Sudan coincided with the revolutionary year of 1848 and the first Slovenian political programme called “United Slovenia” (Zedinjena Slovenija), initiated by Matija Majar-Ziljski, which represented the official beginning of the Slovenian national aspirations. 7 The programme included the demand for the unification of Slovenians into a single political unit within the Habsburg state – that is, the dissolution of the old provincial borders according to the “national” criteria. 8 Slovenians were unable to implement the programme at the time, but they did gain ethnic individuality, name, and integrity.9 Although the 1848 revolution was suppressed by the Imposed Constitution, Slovenians were recognised as a single nation and a part of the Austrian Empire, while the Slovenian language became frequently used in the public sphere. 10 In 1855, the influence of the clergy on the Slovenian public life increased with the concordat with the Catholic Church, which gained control over schools and teaching staff.11 According to Peter Vodopivec,12 the Slovenian national activists of this period gathered around Janez Bleiweis, the editor of the Novice newspaper, believing in compromise and practical training; around Anton Martin Slomšek and Luka Jeran, the editor of Zgodnja Danica, who represented clerical principles; while Simon Jenko and Fran Levstik represented the freethinking youth. 13 In the 1850s, the first two groups dominated the Slovenian cultural scene with their newspapers Novice and Zgodnja Danica.14

2According to Globočnik,15 in the first half of the 19th century, autostereotypes and heterostereotypes also emerged among Slovenians together with the nation-building processes. According to Musek, 16 the fundamental functions of national stereotypes include the identification of the people, the creation of a positive national identity, the simplification of self-esteem, and defensive action. The members of a particular national community use national heterostereotypes for members of other national communities. 17

3. Habsburg Colonial Aspirations

1Slovenians were never part of a colonial state “per se”. In the decade between 1849 and 1859, they were a part of the Austrian Empire (1804–1867). Although it seems, at first glance, that the Habsburg Empire (Austro-Hungarian from 1867 to 1918) had no imperialist and colonial aspirations, certain plans and projects did exist. 18 According to Robert Musil,19 the Habsburg Empire that stretched from the Adriatic to Ukraine possessed colonies within its borders, unlike France and Germany. Therefore, it did not need to compete in the colonial race with England, France, and Germany, as the borders of this multi-ethnic state did not need to be crossed to experience something foreign. However, as Walter Sauer 20 writes, there were certain individuals – “travellers”, “explorers”, and missionaries from the Habsburg Empire – who “explored” the territories overseas with “civilising” or “research missions” in mind. They did so in the contemporaneous political and colonial context, as the government needed information about transport routes, weather conditions, food and water supplies, and the economic and political potentials of the overseas territories. One of the Austrian Empire’s colonial attempts was the Jesuit missionaries’ effort to establish an Austrian colonial presence in today’s Sudan and South Sudan, represented by Ignacij Knoblehar, who was active among the peoples living along the Nile between 1848 and 1858. 21 According to Marko Frelih,22 Knoblehar’s missionary and scientific work was also promoted by Emperor Franz Joseph I, who provided personal patronage of the mission and appropriate material support. Knoblehar’s visit to Vienna stimulated the Austrian interest in dominating East Africa in many ways, as the control of the trade routes along the White Nile was crucial for many European countries. The trade in ivory and natural resources also had a significant economic impact. The English, the French, the Germans, and increasingly the Austrians were aware of this. By establishing the mission, the Austrian government seized the opportunity to become politically and economically active on African soil.

4. The History of Missionaries from the Territory of Today’s Slovenia in Africa

1Evidence exists that Franciscan missionaries from the territory of today’s Slovenia were present in Egypt as early as the 18th century, but not in other parts of Africa.23 Ignacij Knoblehar, born in 1819 in Škocjan, Lower Carniola (Dolenjska), was among the first missionaries to the newly founded Apostolic Vicariate for Central Africa in Khartoum. During this time, the region north of Khartoum (the 12 th northern latitude) was under the administrative and military rule of the Ottoman Empire in Egypt. Although people along the Nile already had their religion, the Church claimed it was possible to found Catholic missions in the area further south of Khartoum.24 The missionaries set up two Catholic missions among the Bari people in Gondokoro (near present-day Juba) and the Kyk people at the St Cross station (near today’s city of Bor). As Frelih writes, the Bari and Kyk people quickly recognised the advantages of the missionaries’ arrival, as they offered protection from slave hunters and provided food during famines. In 1850, Knoblehar returned to Europe, brought an extensive collection of ethnological artefacts of the peoples living along the Nile Valley, and donated it to the Provincial Museum of Carniola ( Kranjski deželni muzej). He gained the patronage of Emperor Franz Joseph I and successfully presented his plans to Pope Pius IX, who appointed him Provicar for Central Africa. 25

1Source: Documentation of Slovene Etnographic Museum (Slovenski etnografski muzej)

2When Knoblehar returned to Sudan for the second time, he was joined by several missionaries, teachers, and artisans from various Austrian provinces, including Carniola (a part of what is nowadays Slovenia).26 Slovenian missionaries who joined the first group were Martin Dovjak, who arrived in Africa in 1851 and died in 1854; Matevž Milharčič, arrived in 1851, died in 1853; Oton Trabant arrived in 1851, died in 1854; Jernej Mozgan, arrived in 1851, died in 1858; and Janez Kocjančič, arrived in 1851, died in 1853. The climatic conditions and malaria, for which there was no cure, caused illness and death among the missionaries.

3During the time of Knoblehar, the slave trade and ivory trade endangered the population along the Nile Valley. Some peoples disappeared entirely, others intermingled, and some moved far away from the navigable rivers.27

4The second group that joined the mission in 1854 included the priest Jožef Lap from Preddvor, the craftsman Franc Bališ, who returned home in 1855, Jakob Šašel, who arrived in 1853 but returned in 1854, and Janez Klančnik, a craftsman. There were also priests from Brixen – Jožef Gostner, Alois Haller, and Martin Ludwig Hansal, whose letters were translated into Slovenian and published in Zgodnja Danica. After Knoblehar died in 1858, there were no missionaries from the Slovenian territory in Africa for about 40 years. As Zmago Šmitek 28 writes, Knoblehar’s co-workers contributed significantly and provided an essential part of the study of the region along the Nile, its inhabitants, and its cultures.

5. Representation of Africa in Zgodnja Danica 1849–1859

1In 1850, Slovenians could familiarise themselves with the missionaries’ presentation of what is nowadays Sudan and South Sudan by reading a monograph written by Vinko Fereri Klun based on the Knoblehar’s diary titled Potovanje po Beli reki (Journey on the White Nile).29 Luka Jeran, the editor of Zgodnja Danica, was a committed supporter of the mission in Central Africa 30 as he, for nearly ten years, regularly published, translated, and probably also censored letters and reports by the missionaries in Egypt, Sudan, and South Sudan.31 Letters from Central Africa were probably widely read, as the newspaper’s advertisement reads: “The newspaper will appear in this spirit as it began, and we hope that it will continue to bring many fascinating letters from Central Africa.”32 According to Frelih,33 after some time, Knoblehar’s close associates and external observers were often critical of the mission he led in Central Africa. However, the Catholic press persistently rejected any negative responses and, through direct propaganda, made sure that the readers did not doubt the Central African mission’s purpose. However, Knoblehar’s death finally confirmed that the illusion of the “great mission” came to an end.

1Source: Franc Jaklič, Apostolski provikar Ignacij Knoblehar in njegovi misijonski sodelavci v osrednji Afriki. Ljubljana: Ljudska knjigarna, 1943

6. Presentation of Africa Based on the Direct Experience of Missionaries Living in Africa

1The following analysis will focus on the most prevalent and repetitive representations of Africa. The letters and articles must be read in the historical context and the context of the mission propaganda. It is important to note that, as Charles Ralph Boxer34 claims, missionaries were, at the time, predisposed to considering themselves the bearers of not only a superior religion but also a superior culture. Our analysis will focus especially on the contrast between the articles written by those who reported directly from Africa and those who never set foot in Africa but wrote about it nevertheless. Although the articles include rich content about the living conditions and people in Egypt and Khartoum, only texts about the people living south of Khartoum will be analysed due to the lack of space.

1Source: Zgodnja Danica, 1851, naslovnica, https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-VHTO993P/be2ff442-ddb9-498c-b995-b45dd7771468/PDF, pridobljeno 27. 10. 2021.

7. Presentation of Africa: Physical Aspects

1One of the most prevalent concepts regarding physical Africa was the claim that it was far away. This is interesting because Africa is, in fact, closer to Europe than, for example, North America. Therefore, we denounce that the concept of the “faraway land” could also signify cultural and not only physical differences. “Beloved Europeans... Beloved Slovenians! I send greetings over fields and mountains, desert and country, kingdoms and sea, cities and villages.”35

2In almost every letter, the climate conditions are mentioned and presented from the European perspective. The focus is on the temperature of the air: “Instead, I have to protect myself from the burning sun so that my brain does not catch fire because the heat is between 26 and 30 degrees Celsius.”36

3Another common topic was illness. Malaria was widespread in the region along the Nile, and at that time, there was no cure for it: “This fever is so widespread around here that everyone in Khartoum and the distant surroundings is ill; in many houses, there is no one healthy to help others, and there is no cure, so poor people suffer without any assistance.” 37

4The glorification of the river Nile and presentations of various animals and plants are omnipresent in the letters. Knoblehar depicts the sight of the Nile as “a magnificent view of the high water.”38 Trabant writes about Egypt as the “blessed land” as well as about the various plants and animals living along the bank of the “good Nile”.39

8. Presentation of Africa: People Living along the White Nile

1Carl Ralph Boxer writes that “by the early seventeenth century, the western intruders were inclined to rate the Asian cultures as the highest, however still below the level of occidental Christendom: the major American civilizations (Aztec, Inca, Maya) as next best; and Black Africans in the bottom position as untamed “savages”.40

2The importance of direct experience and stereotypes based on the prevailing image can be traced in the following passage: “They are not as wild in their behaviour as we often thought. They are friendly, sociable, and eloquent.” 41 Yet the authors of the texts still referred to Africans as “savages”: “I cannot believe that I live in a land of savages.”42

1Zgodnja Danica, 5. 9. 1850, https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-YUYXR7SX/e2e7c63f-364b-4244-894e-a7bc7dd74a29/PDF, pridobljeno 27. 10. 2021.

8.1. Who is a “zamorec/ka”?

1When referring to Africans, several terms were used. The most common include zamorec/zamorka, zamurec/zamurka, zamurče, černak, černuh, černenc, černi, while references to children include words such as zamurček/zamurčica, zamurčik, černuček, černiček. The literal translation of the term “zamorec” would be “a person beyond the sea”. 43 However, not everyone who “came from the other side of the sea” was a “zamorec” for Slovenians, as the articles imply that it is characteristic of the actual “zamorec/ka” that they have a “velvet black skin colour” and “a quick temper”. 44

8.2. The many

1The writings acquainted the readers with the missionaries’ assumption that many Africans could be converted to the Catholic faith. “The praised Nile Valley is quite crowded with people, as there is one village after another here.”45

2One of the characteristics of the texts about Africa is the apparent homogeneity or “non-differentiation” of the continent:46 “Here, however, I had the opportunity to make sure that there was also a significant difference between the savages.”47 However, the early missionary press provides a various and culturally diverse image of the many peoples living in today’s Sudan and South Sudan, named with their original names Bari, Nubians, Dinka, Kyk, Shilluk, Nuer, Chir, Heliab, Bor, Arol, etc.

8.3. Skilful, bright, lively, happy, beautiful

1People living along the White Nile were presented with characteristics perceived as positive, e.g. skilful: “people who are willing and generally able to learn arts and crafts”. 48 African children were characterised as “bright”, but in connection to educating them in the Christian doctrines. “The children are hearty, happy, and very bright: they learn everything – including the Christian doctrine – very quickly.” 49 The missionaries further characterised Africans as lively and happy: … “Our boys exhibit self-satisfied liveliness and joy due to their hot blood.” Moreover, in general, missionaries saw Africans as beautiful in terms of their physical appearance: “A ‘zamurec’ is generally thin, fit and strong… If it seems that ‘zamorci’ are not beautiful, I would disagree and say that they are beautiful people.”50

8.4. Wild, savage, military spirit, hot blood

1Although the majority of the missionaries wrote about Africans favourably and respectfully, they still referred to them as “wild” and “savage”: “I wish that two priests would come to teach with me in schools and present the Catholic religion to the wildest nations.” 51 Later, the missionary press created a stereotype of the helpless African. However, the reports by the missionaries who were actually in Africa reveal that: “They (Africans) possess a belligerent spirit and dedicate a lot of their time to the army – village fighting against village, nation against nation.” 52 The letters by Janez Klančnik, a craftsman, express the most extreme views of all the analysed material. He referred to Africans as inhuman: “These people are more like cattle than people in their behaviour and life because they think nothing, nothing of God, and neither do they care for food or clothing; they are even more ugly than cattle.” 53 Another letter reveals that the missionaries were of a similar opinion as well: “The esteemed missionary says that baptism is slow: savages must first become human, and only then they can become Christians, so it takes time.” 54

8.5. Lazy and “underdeveloped”, slavery

1On the other hand, the missionaries described the people living along the White Nile with negative characteristics such as “lazy” and “underdeveloped”. The authors wrote from the Western viewpoint of development and progress. Furthermore, characterising people in Africa as lazy can be considered a binary opposition to “diligence” (pridnost), which is one of the autostereotypes about Slovenians. 55 Oton Trabant wrote: “There are fertile places along the Nile, yet the people are poor because they are too lazy to cultivate the land.” 56 Slavery was mentioned in the context of the “slave trade”. According to the articles, missionaries fought against it and sympathised with the Africans: “These poor people are sold at the fair like dumb cattle. It is heartbreaking when mothers and children are separated.” 57

8.6. “Superstition”

1Catholic missionaries were completely convinced that only their religion represented “the way, truth, and life.” 58 The disregard for the local African religions is evident, as the missionaries referred to them as superstitions and characterised them with profoundly negative adjectives such as “stupid”, “ugly”, “delusional”, and even “dangerous”. “Many people may have been amazed by such stupid and ugly ‘zamur’ superstitions: let us believe that there is no shortage of such idiots among us who ascribe strength to moderate people. However, are such men not much blacker than unbelieving fools who, in the light of the holy faith, nevertheless attribute the power of God to man? Shame on you, the ugly enemy who steals the glory of God and a good name for men! Woe to you, the ugly fellow who blinds people against the first commandment of God with superstition and empty religions.” The failure to recognise the importance of rain men, a highly esteemed position among Africans – “The ‘zamurec’ is superstitious and pays dearly for his imaginary rain-men,” 59 – turned against the missionaries in time of drought, as they started to be blamed for the lack of rain.60

2The missionary press kept publishing invitations to Slovenians to join the mission in Central Africa. The predominant belief was that only conversion to the Catholic faith and consequently the acceptance of the European way of life could lift Africans out of “poverty”, “underdevelopment”, and the so-called “spiritual darkness”: “Pray that God may have mercy on your black sisters and send devout women to this land who can educate the poor girls; otherwise, they will not learn anything. They do not know how to pray. They do not knit, they do not sew, they do not wash; they are also practically without any clothes, even when they grow up.” 61

1Zgodnja Danica, 9. 10. 1851, https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-OCKF4MTL/152dd4c4-6594-4232-8675-b269502702c0/PDF, pridobljeno 27. 10. 2021.

9. Writing about Africa from Home – Indirect Experience

1Several articles about Africa, published in the Zgodnja Danica newspaper, were written by people who never set foot on the African continent. These texts reveal the collective imagination about Africa and Africans, seen as “exotic” by the Europeans62 of the mid-19th century. It was typical of these texts that the missionaries were glorified and portrayed as people who left the territory of today’s Slovenia to “pull out the thorns in a foreign land”. 63 Missionaries were seen as “heroes” who sacrificed their lives by travelling to a “dangerous faraway land” full of dangerous animals to help the “poor” Africans by leading them to “salvation”. Generally, the “indirect” articles presented Africans as a homogenous entity and “an unfortunate clan that believed in terrible superstitions and was sold into slavery in distant lands.” 64 Africans were mainly presented as “unhappy, ignorant poor black fools”,65 “abandoned, savage, indecent, cruel, inhuman, neglected in soul and body.”66

2Conversely, the land of today’s Slovenia was presented as “free, full of light, joyful” because of the “light of our faith, which is the only right thing.” This is why Slovenians should “show mercy to the poor ‘zamurci’ and help them from their mental and physical slavery. 67 Slovenians saw missionary activities as “charitable acts” and their actions (donation actions) as benevolent help to Africans. Simultaneously, several donation actions, poems, and a theatre play encouraging people to “help the Africans” represented an integral part of Zgodnja Danica.

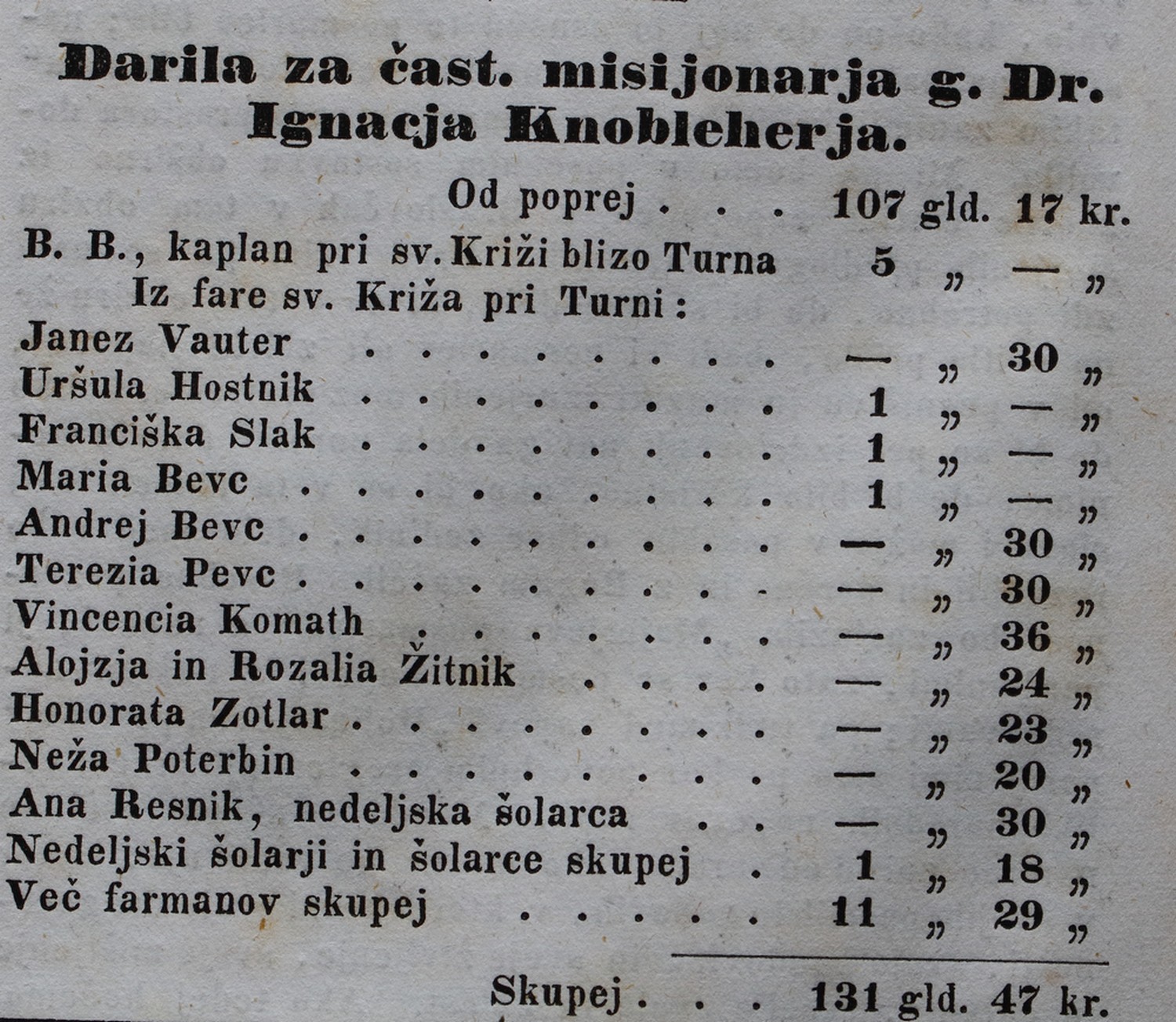

3The request for “gracious donations for the African mission” together with a list of people who have donated money, tools, books, and liturgical objects was regularly published in Zgodnja Danica.68

1Zgodnja Danica, 31. 10. 1850, https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-OOW95BWE/89976a47-bd7c-4542-8231-f50556be861a/PDF, pridobljeno 27. 10. 2021.

4The editor of Zgodnja Danica, Luka Jeran, started the action “Redemption of an African child” (Odkup zamorčka), where Slovenians raised money to purchase African children from the slave markets in Khartoum and Cairo to be raised in the Catholic faith.69 The “godfather” could give a young African a new name, often typically Slovenian; for example, Jožef Kranjski, 70 because “this is how more benefactors can experience the joy of adopting a ‘zamorček’ child.”71 The theatre play focused on whether it was better to help locally or in a “faraway land”. “I want to say that there are many such beggars who are lazy and spend money on drinking. Therefore, it is ten times better to give the money to the ‘zamurcik’”. 72

5Zgodnja Danica reported about Sudanese children brought to the lands of today’s Slovenia to become missionaries and nuns themselves and later spread the Catholic faith among the local people.73 A series of four front-page articles about the broadly attended baptism rites of African children shows the importance of the event for Slovenians. After baptism, the Sudanese children were supposed to become “our (Slovenian) brothers and sisters.” However, they were still perceived as “the Other” among Slovenians, probably because of the colour of their skin. 74

6The excitement of Slovenians about Africa can be summed up with the continuous reports about church bells transported to Gondokoro: “New bells for Khartoum are definitely near Alexandria. God give them luck on the way.” On the other hand, Africans, who were most probably never asked about what they wish, showed what they thought of the missionaries’ activities by hanging the bells from Ljubljana “on a tree, so they (Africans) could ring them.” 75

10. Conclusion

1The Zgodnja Danica newspaper was the most important medium for generating representations and stereotypes about Africa and Africans in the mid-19th century in the territory of what is nowadays Slovenia. The analysed articles include the missionaries’ descriptions of the habits and customs in the African societies living along the Nile at the time, which – in the context of the mission and in combination with the ethnographic collection kept in the Slovenian Ethnographic Museum – can be regarded as a valuable source about Sudan and South Sudan. Moreover, they represent the Slovenian heritage that can also be an excellent source for understanding the mindset of the authors, collectors, and “Slovenians” in general about “the Other” during the decade under consideration. The popularity of stories from Central Africa went hand in hand with the continuous donation actions, while the broadly attended baptism rites of African children in Ljubljana might exhibit elements of contemporaneous “sensationalism” and propaganda in favour of the mission.

2To summarise, the missionaries presented people living along the Nile as “good savages”. They described them with favourable characteristics such as skilful, bright, kind, agile, and therefore as people who had the potential to become good Christians. However, their mission had to address the characteristics perceived as unfavourable: belligerence, laziness, ignorance, and the lack of tools to cultivate the land along the Nile that the missionaries glorified. Therefore, the readers of Zgodnja Danica got an impression that Africa was far away in the physical as well as cultural sense, compared to Slovenian culture. The presentation of various (sometimes also dangerous) animals and plants, unhealthy climate, and recurring illnesses created a stereotype of Africa as a dangerous land. Perhaps this even enhanced the appreciation of the territory that is nowadays Slovenia, consolidating and enhancing the emerging national aspirations of Slovenians. On the one hand, the missionaries presented the various African societies living along the White Nile and therefore not creating a homogeneous sociological category, while at the same time, they homogenised these people by referring to them as uncivilised savages. We can focus on the detailed descriptions of everyday life, habits, accommodations, and rituals of the people living along the Nile, keeping in mind that the texts in question were written in the context of the missionary ideology and the Western perception of development and progress. Authors who never set foot in Africa portrayed it in an even more patronising way, emphasising the stereotype about the helpless African living on a dark continent where poor, unhappy, and abandoned people lived so far away. With the Catholic population in the majority, the Slovenian lands were portrayed as the exact opposite of Africa: as the land of the “true” faith. Africa, on the other side, was depicted as the home of uncivilised and helpless “savages” who could become “civilized” and “developed” only with the assistance and support from Slovenian/European Catholics. The front-page reports about baptisms of young African children, the continuous fundraising for the Central African mission, the action to redeem an African child ( Odkup zamorčka), and the continuous following of the Slovenian church bells on their way to Gondokoro indicate the mass interest of Slovenians in “helping” the “poor Africans”.

3Perhaps besides describing Africans, the articles reveal even more about Slovenians themselves at that time. The formation of the Slovenian nation and the first claims to the Slovenian entity “needed” “the Others” and therefore created a heterostereotype about Africans as the complete opposite to the autostereotype of Slovenians as diligent, cultivated, white, hard-working people. The period under consideration coincided with the 1848 revolution and the subsequent neo-absolutist. Perhaps the popularity of reports from Africa and the recurring donation actions of Slovenians “to help the poor Africans” was one of the elements contributing to the process of the Slovenian national perception, which could be, in a way, also constructed around the identity of those who “benevolently help” the “poor ‘zamorci’.”

Sources and Literature

- Bach, Ulrich E.. Tropics of Vienna. Colonial Utopias of the Habsburg Empire. Berghahn Books: New York, Oxford, 2016.

- Boxer, C. R.. The Church Militant, and Iberian Expansion, 1440–1770. Baltimore/ London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1978.

- Frelih, Marko. Sudanska misija 1848–1858, Ignacij Knoblehar - misijonar, raziskovalec Belega Nila in zbiralec afriških predmetov = Sudan mission 1848–1858, Ignacij Knoblehar - Missionary, Explorer of the White Nile and Collector of African Objects. Ljubljana: Slovenski etnografski muzej, 2009. Available at https://www.etno-muzej.si/files/sudanska_misija.pdf.

- Frelih, Marko. Slovenci ob Belem Nilu - Dr. Ignacij Knoblehar in njegovi sodelavci v Sudanu sredi 19. stoletja = Slovenians Along the Nile - Dr. Ignacij Knoblehar and his Associates in Sudan in the mid 19th Century. Stična: Muzej krščanstva na Slovenskem, 2019. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-1H55SW1C/e095c5a2-de85-4722-8e57-d731a72be84e/PDF.

- Globočnik, Damir. »Gosposka škrijcasta suknja in slovenstvo: izbor stereotipnih upodobitev v slovenski karikaturi.« In Irena Novak – Popov (ed.). 43. seminar slovenskega jezika, literature in kulture. Ljubljana: Filozofska fakulteta, 2008. Available at http://centerslo.si/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/43.-SSJLK.pdf.

- Granda, Stane. »Revolucionarno leto 1848 in Slovenci.« In Slovenska kronika XIX. stoletja. 1800–1860, 303–12. Ljubljana: Nova revija. 2001.

- Gundani, Paul. »Views and Attitudes of Missionaries Toward African Religion in Southern Africa During the Portuguese Era.« In Religion and Theology, Vol 11, Issue 3-4. (Brill: Leiden, 2004): 298– 312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/157430104X00140.

- Jaklič, Franc. Apostolski provikar Ignacij Knoblehar in njegovi misijonski sodelavci v osrednji Afriki. Ljubljana: Ljudska Knjigarna, 1943.

- Janzen, John. Catastrophe Africa: Getting through Stereotypes and Qick Fixes to the Social Reproduction of Health (2004). Available at https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/14950/Janzen_Representation,Ritual,&Social_Renewal.pdf;jsessionid=BC611D806C885B0C73373C59795D1408?sequence=1.

- Kovačev, Asja Nina. »Nacionalna identiteta in slovenski avtostereotip. « In Psihološka obzorja, Vol. 6, Nr. 4 (1997): 49–63. Ljubljana: Društvo psihologov Slovenije. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-9TA88HA6/815fa898-0128-4bca-8714-607a93ea4f68/PDF.

- Knoblehar, Ignacij and Vinko Fereri Klun. Potovanje po Béli reki. Ljubljana: Kleinmayer in F. Bamberg, 1850. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-3ZGI0PGW/1003e183-e708-4bce-83e8-c295f1d62af9/PDF.

- Melik, Vasilij. »Slovenci skozi čas. « In Slovenci 1848–1918. Razprave in članki,19-22. (Maribor: Litera, 2002), 19–22. Available at https://www.sistory.si/11686/file2282.

- Melik, Vasilij. »Leto 1848 v slovenski zgodovini.« In Slovenci 1848–1918. Razprave in članki, 36–50. Maribor: Litera, 2002. Available at https://www.sistory.si/11686/file2282.

- Musek, Janek. Psihološki portret Slovencev. Ljubljana: Znanstveno in publicistično središče, 1994.

- Ognjišče. »Luka Jeran.« (2008). Available at https://revija.ognjisce.si/revija-ognjisce/27-obletnica-meseca/1837-luka-jeran.

- Prunk, Janko. Kratka zgodovina Slovenije. Založba Grad: Ljubljana, 2008.

- Slovar slovenskega knjižnega jezika. Available at www. fran. si.

- Sauer, Walter. »Habsburg Colonial: Austria-Hungary's Role in European Overseas Expansion Reconsidered.« In Austrian Studies Vol. 20, Colonial Austria: Austria and the Overseas (2012): 5–23, https://doi.org/10.5699/Austrian studies.20.2012.0005. and https://doi.org/10.5699/Austrian studies.20.2012.0005..

- Studen, Andrej. »Jožef Kranjski in drugi Jeranovi zamorčki,« In Slovenska kronika XIX. stoletja.1800–1860. 429–30. Ljubljana: Nova revija. 2001.

- Šmitek, Zmago. Klic daljnih svetov, Slovenci in neevropske kulture. Ljubljana: Založba Borec, 1986.

- Ule, Mirjana. Socialna psihologija: Analitični pristop k življenju v družbi. Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2009.

- Vodopivec, Peter. Od Pohlinove slovnice do samostojne države. Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2006.

- Zajc, Marko and Janez Polajnar. Naši in vaši. Iz zgodovine slovenskega časopisnega diskurza v 19. in začetku 20. stoletja. Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, 2012. Available at https://www.mirovni-institut.si/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/nasi-in-vasi-mediawatch-23.pdf.

- Zwitter, Fran. »Slovenci in Habsburška monarhija.« In O slovenskem narodnem vprašanju, Vasilij Melik (ed.), 56. Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 1990.

- Zgodnja Danica, 1850-1857.

- 1850

- "Misijonar Dr. Ignaci Knobleher," 5. 9. 1850. Available at: https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-YUYXR7SX/e2e7c63f-364b-4244-894e-a7bc7dd74a29/PDF.

- "Darila za čast. misijonarja g. Dr. Ignacja Knobleherja," 31. 10. 1850. Available at:https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-OOW95BWE/89976a47-bd7c-4542-8231-f50556be861a/PDF.

- 1851

- "Zgodnja Danica," 1851, naslovnica. Available at:https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-VHTO993P/be2ff442-ddb9-498c-b995-b45dd7771468/PDF.

- "Nekoliko iz pisma misjonarja gosp. Kociančiča," 9. 10. 1851. Available at:https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-OCKF4MTL/152dd4c4-6594-4232-8675-b269502702c0/PDF.

- 1852

- Knoblehar, Ignacij. »Misijonska naznanila g. Dr. Knobleharja do središniga odbora Marijne družbe na Dunaju.« Zgodnja Danica, 19. 7. 1852. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-RVRXMSFE/9d393e9b-9aff-4c6e-b934-6979d298fc24/PDF.

- Knoblehar, Ignacij. »Misijonska naznanila Dr. Knobleharja do središniga odbora Mariine družbe na Dunaju.« Zgodnja Danica, 1. 7. 1852. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-BVNGDEE8/4425c841-1c79-4a5f-b5ff-992994a593ce/PDF.

- Partel, Jožef. »Sužnji Kamov rod in ladija rješenja.« Zgodnja Danica, 8. 4. 1852. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-FCRTC2X5/8f0449b9-666e-4612-8460-a27d0876ed96/PDF.

- Trabant, Oton. »Iz pisma misionarja gospotla Otona Trabanta iz Hartuma.« Zgodnja Danica, 7. 11. 1852. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-KHABNOBZ/637a4bce-a7f3-4850-b5d8-6c1d38cf2fed/PDF.

- Trabant, Oton. »Pismo misijonarja g. Otona Trabanta do milostiviga visokočastitljiviga Lavantinskiga kneza in škofa.« Zgodnja Danica, 17. 6. 1852. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-JMTYP75Y/d3197e9a-71bc-4eba-9d4d-c00983de8d66/PDF.

- Unsigned. »Slovenilka.« Zgodnja Danica, 5. 2. 1852. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-OUE3LWQC/a2dfae4b-1c88-496d-89cf-0b535b94351b/PDF.

- 1853

- Janez (undersigned as Janez and the reader of Danica). »Zamurček Jožef Kranjski.« Zgodnja Danica, 14. 7. 1853. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-W15KGZ5R/7823391a-2ce7-43d7-b72b-af9802bfb28d/PDF.

- Janez (undersigned as Janez and the reader of Danica). »Jožef Krajnski.« Zgodnja Danica, 21. 7. 1853. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-2CL9UWFE/e1bf9b34-4fcf-4fbb-ac17-7de0f97aa875/PDF.

- Kocijančič, Janez. »Pisma gospod Kocijančiča, misijonarja v Hartumu VIII.« Zgodnja Danica, 19. 5. 1853. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-PWRUNMFK/2aaf925f-1440-4e75-967c-f4a6fa0c19b0/PDF.

- Trabant, Oton. »Pismo misijonarja Otona Trabanta do prečestitega grova Lavantinskega.« Zgodnja Danica, 9. 6. 1853. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-6VCDF60N/1d375854-01b7-43a3-87f3-e87232116a92/PDF.

- Unsigned. “Mili darovi,” Zgodnja Danica, 21. 4. 1853, 68. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-DTAJWZQN/6e349b00-4fee-4f78-be3a-3ed18559db32/PDF.

- Unsigned. »Naročevanje na Zgodnjo Danico.« Zgodnja Danica, 16. 6. 1853. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-9HPO6IAZ/9116025f-9f81-4f97-8828-5d0e14264e55/PDF.

- 1854

- Gostner, Jožef. »Pismo gosp. Misijonarja Jožefa Gostnerja iz Hartuma.« Zgodnja Danica, 18. 5. 1854. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:doc-3FI1HQ6R/da3f28cb-295c-425c-ab21-cbf36960dd81/PDF.

- Klančnik, Janez. »Iz Hartuma. Nekoliko iz pisma, ki ga je pisal rokodelec Janez Klančnik vrisokocastitemu g. J. Volču, duhovnemu vodniku v ljubljanski duhovsnici.« Zgodnja Danica, 6. 4. 1854. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-MVJEBMUT/2ec3c006-97a1-4627-9991-026a53fd66dc/PDF.

- 1855

- Unsigned. »Z Bele reke v srednji Afriki.« Zgodnja Danica, 25. 1. 1855. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-EPH0AEZH/14bdb8c5-c2ec-475e-8138-1c450999a179/PDF.

- 1856

- Knoblehar, Ignacij. »Misijonska naznanila prečastitega gospoda provikarja Dr. Ignacija Knobleharja do kardinala Franconija- vodja v Rimski propagandi. « Zgodnja Danica, 11. 12. 1856. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-XQVFSFK1/5502804d-45f2-4318-a11d-7f87e85d32a1/PDF.

- Unsigned. »Iz srednje Afrike.« Zgodnja Danica, 31. 1. 1856. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-JT6FQXTF/15c39d1c-b428-47be-8d9f-f3c7d0ccbdee/PDF.

- Unsigned. »Kerst ljubljanski nunski cerkvi in ubogi zamorski otročiči.« Zgodnja Danica, 9. 11. 1856. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-Y1CS97C8/f030342b-d2c5-4e1d-8ba6-d0c287fb6f33/PDF.

- Unsigned. »Kerst v ljubljanski nunski cerkvi in ubogi zamorski otročiči.« Zgodnja Danica, 16. 11. 1856. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-GAGSGQMX/f26a2981-9f38-488d-ab10-31f4e2d9bc12/PDF.

- Unsigned. »Kerst v ljubljanski nunski cerkvi in ubogi zamorski otročiči.« In Zgodnja Danica, 23. 11. 1856. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-BSGFGCP3/1dadf897-d701-4a73-8268-f58139d1577b/PDF.

- 1857

- Klančnik, Janez. »Iz pisma Janeza Klančnika od Sv. Križa pri Beli reki. « Zgodnja Danica, 9. 7. 1857. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-FUDULRIC/812ebe98-c9fa-4ee4-a9de-edd3e049c4a5/PDF.

- Klančnik, Janez. »Iz pisma Janeza Klančnika od Sv. Križa pri Beli reki.« Zgodnja Danica, 16. 7. 1857. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-49C67DM2/38a8d4e4-4fac-4ba7-91a8-a59bed1636e4/PDF .

- Unsigned. »Ogled po Slovenskim.« Zgodnja Danica, 2. 7. 1857. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-GR0AYXOW/a4f8e19a-9e1e-4701-9f1b-678f6bb994e2/PDF.

- Unsigned. »Kerst dveh zamorskih dekličev v Škofji Loki.« Zgodnja Danica, 23. 4. 1857. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-TALFSTUO/884cadc6-5126-49b0-9cd9-aa3b29de3d0e/PDF.

- 1850

Anja Polajnar

PRIKAZ AFRIKE V ČASOPISU ZGODNJA DANICA OD LETA 1849 DO 1859

POVZETEK

1Ignacij Knoblehar, rojen v Škocjanu na Dolenjskem (danes del Slovenije), je v desetletju 1849–1858 vodil katoliški misijon v Srednji Afriki med ljudmi, ki so živeli ob Belem Nilu v današnjem Sudanu in Južnem Sudanu. Knoblehar in njegovi sodelavci so v omenjenem desetletju redno pisali pisma, poročila in pesmi, v katerih so opisovali svoje poglede na tamkajšnje razmere in ljudi. Pisma so bila redno objavljana v časopisu Zgodnja Danica, urednik Luka Jeran pa jih je cenzuriral. To obdobje sovpada z desetletjem po prelomnem letu 1848, ko so Slovenci začeli graditi svojo državo in zahtevali avtonomijo kot del avstrijskega cesarstva. V tem desetletju je slovenska prizadevanja za uveljavitev naroda zatrl neoabsolutistični režim, poleg tega pa sta bila dovoljena le dva časopisa v slovenskem jeziku s pretežno konservativno in katoliško vsebino. Eden od njiju je bil časopis Zgodnja Danica, ki je zato takrat verjetno predstavljal redno branje med Slovenci in Slovenkami. Analiza razkriva razliko med članki, ki temeljijo na neposredni izkušnji iz Afrike, in tistimi, ki so jih napisali avtorji, ki na tej celini nikoli niso bili, a so kljub temu pisali o njej. Misijonarji so deželo in ljudi, ki so živeli ob Belem Nilu, predstavljali z zahodne perspektive, pri čemer so omenjali »nezdrave« podnebne razmere, izjemno vročino, nevarne živali, bolezni in odročnost.

2Po eni strani so ljudi, živeče na ozemlju, ki je danes Sudan in Južni Sudan, predstavljali kot bistre, lepe, prijazne, srečne in spretne. Po drugi strani pa so bili opisani tudi kot leni, nerazviti, necivilizirani in bojeviti. Nekatera besedila so opisovala ljudi kot nečloveške in omalovaževala njihovo vero, ki so jo imenovali »vraževerje«. Članki ne homogenizirajo celine v eno samo enoto, temveč opisujejo različna ljudstva, ki živijo ob Nilu, in jih imenujejo z njihovimi izvirnimi imeni.

3Drugi del analize se osredotoča na besedila, igre in pesmi avtorjev, ki niso nikoli stopili na afriško celino. Ta besedila konstruirajo in homogenizirajo ljudi, ki živijo v Afriki, in jim pripisujejo lastnosti, kot so »nemoč« in »revnost«, življenje v »temni« deželi, po drugi strani pa poveličujejo misijonarje, ki so po njihovem mnenju žrtvovali svoja življenja, zapustili dom in odpotovali »daleč« v »nevarne« kraje, da bi »pomagali« »revnim« Afričanom. Nasprotno pa so ljudje in področje, kjer je danes Slovenija, prikazani kot »razsvetljeni«, »civilizirani« in »razviti«. Dobrodušni Slovenci naj bi »pomagali« Afričanom s sodelovanjem pri različnih »donatorskih« akcijah, s katerimi so po eni strani zbirali sredstva za Srednjeafriško katoliško misijo, po drugi strani pa med slovenskim prebivalstvom širili velik ugled misije. Slovenci so poleg tega vsebine, ki so se nanašale na Afriko in Afričane ter Afričanke, dojemali kot »fascinantne« in najverjetneje tudi zato kupovali revijo. Analizirana besedila kažejo, da so se prebivalci Slovenije videli kot pravo nasprotje Afričanov in Afričank, zato so želeli in znali pomagati tistim, za katere so menili, da živijo v »slabših« razmerah. Nekateri stereotipi in predsodki o Afriki in Afričanih ter Afričankah iz 19. stoletja so še dandanes občasno del medijskega diskurza. Razumevanje njihovega izvora lahko pomaga pri njihovem premagovanju, saj preprečuje reprodukcijo v sodobnem javnem diskurzu.

* Mag., PhD student, University of Nova Gorica, Vipavska cesta, SI-5000 Nova Gorica; anja.polajnar@gmail.com

1. It shall be noted that in the period under consideration (1849–1859), Slovenians were emerging as a nation. Furthermore, by referring to Africans, the author (AP) also generalises the heterogeneity of the people living in the African continent.

2. It shall be noted that we are referring to the area of today’s Slovenia, which was, in the analysed period, a part of the Austrian Empire, which became the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867.

3. Vasilij Melik, “Slovenci skozi čas,” in: Slovenci 1848–1918. Razprave in članki (Maribor: Litera, 2002), 19–22.

4. Ibidem, 27.

5. Fran Zwitter, “Slovenci in Habsburška monarhija,” in: O slovenskem narodnem vprašanju (Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 1990), 56.

6. Marko Zajc and Janez Polajnar, “Zamorcev ne bomo umivali. Podoba zamorca v slovenskem časopisju v 19. in začetku 20. stoletja,” in: Naši in vaši. Iz zgodovine slovenskega časopisnega diskurza v 19. in začetku 20. stoletja (Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, 2012). Available at https://www.mirovni-institut.si/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/nasi-in-vasi-mediawatch-23.pdf.

7. Vasilij Melik, “Leto 1848 v slovenski zgodovini,” in: Slovenci 1848–1918. Razprave in članki (Maribor: Litera, 2002), 36.

8. Ibid., 28.

9. Janko Prunk, Kratka zgodovina Slovenije (Založba Grad: Ljubljana, 2008), 73.

10. Stane Granda, “Revolucionarno leto 1848 in Slovenci,” in: Slovenska kronika XIX. stoletja. 1800–1860 (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 2001), 303–12.

11. Peter Vodopivec, Od Pohlinove slovnice do samostojne države (Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2006), 68.

12. Ibid., 69

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid., 70. With its publishing activities, the clergy exerted a general influence on the Slovenian public. The books and publications had a Catholic and patriotic content, written in a moral and educational tone. In 1849 and 1851, however, Campe’s Version of Robinson Crusoe was translated into Slovenian, while in 1853, a Slovenian translation of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published as well.

15. Damir Globočnik, “Gosposka škrijcasta suknja in slovenstvo: izbor stereotipnih upodobitev v slovenski karikaturi,” in: Irena Novak – Popov (ed.), 43. seminar slovenskega jezika, literature in kulture (Ljubljana: Filozofska fakulteta, 2008), 156. Available at http://centerslo.si/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/43.-SSJLK.pdf.

16. Janek Musek, Psihološki portret Slovencev (Ljubljana: Znanstveno in publicistično središče, 1994), 32, 33.

17. Ibid. Mirjana Ule, Socialna psihologija: Analitični pristop k življenju v družbi (Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2009), 180.

18. Walter Sauer, “Habsburg Colonial: Austria-Hungary’s Role in European Overseas Expansion Reconsidered,“ in: Austrian Studies, Vol. 20, Colonial Austria: Austria and the Overseas (2012): 5, https://doi.org/10.5699/austrianstudies.20.2012.0005..

19. Robert Musil and Ulrich E. Bach, Tropics of Vienna. Colonial Utopias of the Habsburg Empire (New York, Oxford: Berghahn, 2016), 2.

20. Ibid., 7–12.

21. Ibid., 8.

22. Marko Frelih, Sudanska misija 1848–1858, Ignacij Knoblehar – misijonar, raziskovalec Belega Nila in zbiralec afriških predmetov = Sudan mission 1848–1858, Ignacij Knoblehar – Missionary, Explorer of the White Nile and Collector of African Objects (Ljubljana: Slovenski etnografski muzej, 2009), 141. Available at https://www.etno-muzej.si/files/sudanska_misija.pdf.

23. Zmago Šmitek, Klic daljnih svetov, Slovenci in neevropske kulture (Ljubljana: Založba Borec, 1986), 109–11.

24. Frelih, Sudanska misija, 11–14.

25. Ibid., 14–18.

26. Ibid., 24.

27. Ibid., 67.

28. Ibid., 111–16.

29. Ignacij Knoblehar and Vinko Fereri Klun, Potovanje po Béli reki (Ljubljana: Ign. pl. Kleinmayerja in Fedor Bamberga, 1850). Available at http://www.dlib.si/?URN=URN:NBN:SI:DOC-3ZGI0PGW.

30. Marko Frelih, Slovenci ob Belem Nilu – Dr. Ignacij Knoblehar in njegovi sodelavci v Sudanu sredi 19. stoletja = Slovenians Along the Nile - Dr Ignacij Knoblehar and his associates in Sudan in the mid-19th Century (Stična: Muzej krščanstva na Slovenskem, 2019), 22. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-1H55SW1C/e095c5a2-de85-4722-8e57-d731a72be84e/PDF.

31. Frelih, Sudanska misija, 15.

32. Unsigned (probably translated by Luka Jeran from the letters of Josef Gostner and Anton Ueberbacher), “Naročevanje na Zgodnjo Danico,” Zgodnja Danica, 16. 6. 1853. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-9HPO6IAZ/9116025f-9f81-4f97-8828-5d0e14264e55/PDF.

33. Frelih, Sudanska misija, 14.

34. C. R. Boxer, The Church Militant and Iberian Expansion, 1440–1770 (Baltimore, London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1978), 40.

35. Janez Klančnik, “Iz Hartuma. Nekoliko iz pisma, ki ga je pisal rokodelec Janez Klančnik visokočastitemu g. J. Volču, duhovnemu vodniku v ljubljanski duhovsnici,” Zgodnja Danica, 6. 4. 1854, 64, 65. Available at http://www.dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-MVJEBMUT.

36. Oton Trabant, “Iz pisma misionarja gospotla Antona Trabanta iz Hartuma,” Zgodnja Danica, 7. 11. 1852, 161. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-KHABNOBZ/637a4bce-a7f3-4850-b5d8-6c1d38cf2fed/PDF.

37. Jožef Gostner, “Pismo gosp. Misijonarja Jožefa Gostnerja iz Hartuma,” Zgodnja Danica, 18. 5. 1854, 86. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:doc-3FI1HQ6R/da3f28cb-295c-425c-ab21-cbf36960dd81/PDF.

38. Ignacij Knoblehar, “Misijonska naznanila Dr. Knobleharja do središniga odbora Mariine družbe na Dunaju,” Zgodnja Danica, 1. 7. 1852, 106. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-BVNGDEE8/4425c841-1c79-4a5f-b5ff-992994a593ce/PDF.

39. Oton Trabant, “Pismo misjonarja Antona Trabanta do prečastitljiviga knezoškofa Lavantinskiga,” Zgodnja Danica, 17. 6. 1852, 99. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-JMTYP75Y/d3197e9a-71bc-4eba-9d4d-c00983de8d66/PDF.

40. Boxer, The Church Militant.

41. Unsigned (probably translated by Luka Jeran from the letters of Josef Gostner and Anton Ueberbacher), “Iz srednje Afrike,” in: Zgodnja Danica, 31. 1. 1856, 17. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-JT6FQXTF/15c39d1c-b428-47be-8d9f-f3c7d0ccbdee/PDF.

42. Ibid., 18

43. The dictionary of Slovenian Literary Language states that nowadays the term “zamorec” is a derogatory term for a person of “black race”. The synonym is “črnec”. “Zamorec” is also a term for a person who works hard and who has the hardest and worst-paid job – e.g., he works as a “zamorc”. – Slovar slovenskega knjižnega jezika. Available at www.fran.si.

44. Unsigned, “Kerst v ljubljanski nunski cerkvi in ubogi zamorski otročiči,” Zgodnja Danica, 16. 11. 1856. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-GAGSGQMX/f26a2981-9f38-488d-ab10-31f4e2d9bc12/PDF

45. Oton Trabant, “Pismo misijonarja g. Otona Trabanta do milostiviga visokočastitljiviga Lavantinskiga kneza in škofa,” Zgodnja Danica, 17. 6. 1852, 99. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-JMTYP75Y/d3197e9a-71bc-4eba-9d4d-c00983de8d66/PDF.

46. John Janzen, Catastrophe Africa: Getting through Stereotypes and Quick Fixes to the Social Reproduction of Health (2004). Available at https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/14950/Janzen_Representation,Ritual,&Social_Renewal.pdf;jsessionid=BC611D806C885B0C73373C59795D1408?sequence=1.

47. Ignacij Knoblehar, “Misijonska naznanila g. Dr. Knobleharja do središniga odbora Marijne družbe na Dunaju,” Zgodnja Danica, 19. 7. 1852, 134. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-RVRXMSFE/9d393e9b-9aff-4c6e-b934-6979d298fc24/PDF.

48. Unisgned, “Z Bele reke v srednji Afriki,” Zgodnja Danica, 25. 1. 1855, 14. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-EPH0AEZH/14bdb8c5-c2ec-475e-8138-1c450999a179/PDF.

49. Ibid.

50. Unsigned (probably translated by Luka Jeran from the letters of Josef Gostner and Anton Ueberbacher), “Iz srednje Afrike,” Zgodnja Danica, 31. 1. 1856, 17. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-JT6FQXTF/15c39d1c-b428-47be-8d9f-f3c7d0ccbdee/PDF.

51. Ignacij Knoblehar, “Misijonska naznanila prečastitega gospoda provikarja Dr. Ignacija Knobleharja do kardinala Franconija – vodja v Rimski propaganda,” Zgodnja Danica, 11. 12. 1856. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-XQVFSFK1/5502804d-45f2-4318-a11d-7f87e85d32a1/PDF.

52. Unsigned (probably translated by Luka Jeran from the letters of Josef Gostner and Anton Ueberbacher), “Iz srednje Afrike,” Zgodnja Danica, 31. 1. 1856, 17. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-JT6FQXTF/15c39d1c-b428-47be-8d9f-f3c7d0ccbdee/PDF.

53. Janez Klančnik, “Iz pisma Janeza Klančnika od Sv. Križa pri Beli reki,” Zgodnja Danica, 16. 7. 1857, 116. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-49C67DM2/38a8d4e4-4fac-4ba7-91a8-a59bed1636e4/PDF.

54. Janez Klančnik, “Iz pisma Janeza Klančnika od Sv. Križa pri Beli reki,” Zgodnja Danica, 9. 7. 1857, 112. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-FUDULRIC/812ebe98-c9fa-4ee4-a9de-edd3e049c4a5/PDF.

55. Asja Nina Kovačev, “Nacionalna identiteta in slovenski avtostereotip,” Psihološka obzorja Vol. 6, Nr. 4 (1997): 59. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-9TA88HA6/815fa898-0128-4bca-8714-607a93ea4f68/PDF.

56. Oton Trabant, “Pismo misijonarja Otona Trabanta do prečestitega grova Lavantinskega,” Zgodnja Danica, 9. 6. 1853, 95. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-6VCDF60N/1d375854-01b7-43a3-87f3-e87232116a92/PDF.

57. Janez Kocijančič, “Pisma gospod Kocijančiča, misijonarja v Hartumu VIII,” Zgodnja Danica, 19. 5. 1853, 81. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-PWRUNMFK/2aaf925f-1440-4e75-967c-f4a6fa0c19b0/PDF.

58. Paul Gundani, “Views and Attitudes of Missionaries Toward African Religion in Southern Africa During the Portuguese Era,” Religion and Theology, Vol 11, Issue 3–4 (2004): 300. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/157430104X00140.

59. Unsigned (probably translated by Luka Jeran from the letters of Josef Gostner and Anton Ueberbacher), “Iz srednje Afrike,” Zgodnja Danica, 31. 1. 1856, 17. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-JT6FQXTF/15c39d1c-b428-47be-8d9f-f3c7d0ccbdee/PDF.

60. Frelih, Sudanska misija, 15.

61. Janez Kocijančič, “Pisma gospod Kocijančiča, misijonarja v Hartumu VIII,” Zgodnja Danica (Ljubljana: Jožef Blaznik, 1853b), 66. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-DTAJWZQN/6e349b00-4fee-4f78-be3a-3ed18559db32/PDF.

62. For more about the 19th-century “human zoos” and the way in which people were put on display as a form of entertainment in many cities across the “Western” world as well as in Trieste, which was part of the Habsburg Monarchy, see the article by Daša Ličen, “ Razstaviti drugega/Saidin prihod v Trst,” Glasnik Slovenskega etnološkega društva = Bulletin of the Slovenian Ethnological Society, Nr. 1/2 (Ljubljana: Slovensko etnološko društvo, 2018): 5–15.

63. See more in Unsigned, “Slovenilka the poem,” Zgodnja Danica, 5. 2. 1852, 21. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-OUE3LWQC/a2dfae4b-1c88-496d-89cf-0b535b94351b/PDF.

64. Jožef Partel, “Sužnji Kamov rod in ladija rešenja,” Zgodnja Danica, 8. 4. 1852, 57. Available at https://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-FCRTC2X5/8f0449b9-666e-4612-8460-a27d0876ed96/PDF.

65. Unsigned (probably translated by Luka Jeran from the letters of Josef Gostner and Anton Ueberbacher), “Ogled po Slovenskim,” Zgodnja Danica, 2. 7. 1857, 108. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-GR0AYXOW/a4f8e19a-9e1e-4701-9f1b-678f6bb994e2/PDF.

66. Unsigned (probably written by the editor Luka Jeran), “Kerst dveh zamorskih dekličev v Škofji Loki,” Zgodnja Danica, 23. 4. 1857, 65. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-TALFSTUO/884cadc6-5126-49b0-9cd9-aa3b29de3d0e/PDF.

67. Unsigned (probably written by Luka Jeran), “Kerst v ljubljanski nunski cerkvi in ubogi zamorski otročiči,” Zgodnja Danica, 23. 11. 1856, 187. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-BSGFGCP3/1dadf897-d701-4a73-8268-f58139d1577b/PDF.

68. Unsigned (probably translated by Luka Jeran from the letters of Josef Gostner and Anton Ueberbacher), “Mili darovi,” Zgodnja Danica, 21. 4. 1853, 68. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-DTAJWZQN/6e349b00-4fee-4f78-be3a-3ed18559db32/PDF.

69. Andrej Studen, “Jožef Kranjski in drugi Jeranovi zamorčki,” in: Slovenska kronika XIX. stoletja. 1800–1860 (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 2001), 429, 430.

70. Janez (in bralec Danice), “Zamurček Jožef Kranjski,” Zgodnja Danica, 14. 7. 1853, 116. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-W15KGZ5R/7823391a-2ce7-43d7-b72b-af9802bfb28d/PDF.

71. “Luka Jeran,” Ognjišče. Available at https://revija.ognjisce.si/revija-ognjisce/27-obletnica-meseca/1837-luka-jeran.

72. See “Jožef Krajnski,” Zgodnja Danica, 21. 7. 1853, 119. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-2CL9UWFE/e1bf9b34-4fcf-4fbb-ac17-7de0f97aa875/PDF.

73. For a detailed description of the baptism rite, see: Unsigned, “Kerst ljubljanski nunski cerkvi in ubogi zamorski otročiči,” Zgodnja Danica, 9. 11. 1856, 178. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-Y1CS97C8/f030342b-d2c5-4e1d-8ba6-d0c287fb6f33/PDF.

74. Frelih, Sudanska misija, 18.

75. Unsigned, “Ogled po Slovenskim,” Zgodnja Danica, 2. 7. 1857, 109. Available at http://www.dlib.si/stream/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-GR0AYXOW/a4f8e19a-9e1e-4701-9f1b-678f6bb994e2/PDF.