Encoding Textual Variants of the Early Modern Slovenian Poetic Texts in TEI

UDC: 004.934:821.163.6-1"16/18"

IZVLEČEK

ZAPIS VARIANTNOSTI STAREJŠIH SLOVENSKIH PESNIŠKIH BESEDIL V TEI

1V prispevku obravnavamo problematiko zapisa verza in variantnih mest v znanstvenokritični izdaji Foglarjevega rokopisa, štajerske baročne pesmarice iz sredine 18. stoletja. Najprej prikažemo diplomatični zapis verza v izbranih problematičnih primerih. V nadaljevanju predstavimo metodo, uporabljeno za izdelavo kritičnega aparata variantnih mest. Temeljno besedilo, tj. Foglarjev rokopis, je primerjano z verzijami v osmih drugih rokopisih in tiskih iz 18. in začetka 19. stoletja. Variantna mesta so označena z elementi XML po Smernicah TEI (TEI Guidelines) kot enote kritičnega aparata. Prikazujemo nekaj primerov detajliranega označevanja rime, stopice, zamenjav verzov ter variantnih razlik na pravopisni, glasoslovni in leksikalni ravnini jezika. Na koncu orišemo več možnosti spletnega prikaza elektronskega diplomatičnega besedila. Pokazala se je potreba po prilagodljivosti teh orodij slovenskemu literarnemu izročilu.

2Ključne besede: slovensko slovstvo, Foglarjev rokopis, znanstvenokritična izdaja, kritični aparat, variantnost besedila, TEI

ABSTRACT

1The paper deals with the problem of encoding the verses and textual variants in the critical edition of Foglar’s Manuscript, a Styrian Baroque hymn book from the mid-eighteenth century. We first show the diplomatic transcript of the verse in selected problematic cases, after which we present the method applied to produce a critical apparatus for approaching textual variants. The base text, i.e. Foglar’s Manuscript, is compared with versions in eight other manuscripts and prints from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Variants are encoded with XML elements according to the TEI Guidelines as units of the critical apparatus. We highlight some examples of the detailed encoding of rhymes, feet, verse replacements, and textual variants on the spelling, vocabulary and lexical levels of the language. To conclude, we present a number of possibilities for the online display of the electronic diplomatic transcript. The need for the adaptability of these tools to the Slovenian literary tradition is evident.

2Keywords: Slovenian literature, Foglar’s Manuscript, critical edition, critical apparatus, textual variance, TEI

1. Introduction

1The texts that have been passed down to us over time via manuscript culture were transcribed from witness to witness over a long period of time. In this kind of textual transmission (Textüberlieferung), many textual variations appear in the text, which are called (variant) readings (Lesarten) or variants (Überlieferungsvarianten). Variant readings can be merely scribal mistakes or “errors”, but even these can range from using the wrong letter to the omission of an entire line. Variants, however, can also be the scribe’s intentional modifications of the text, including anything from orthographic differences and various word forms to major interventions in the text, such as additions, omissions, word order changes, transpositions of whole paragraphs or stanzas, etc. Textual variance also occurs in printed texts in general, that is, in the culture of the printed book: as soon as the same text is published again, variant readings start to appear, albeit not quite as extensively as in the handwritten tradition. Since very few medieval manuscript texts are preserved in the Slovenian language, the problem of textual variation in Slovenian only appears in the early modern age, especially in the Baroque era. Among the most common examples of the Slovenian transcription tradition are those of the Baroque texts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Among prose texts, for example, the Črnovrški Manuscript,1 the manuscripts on the Antikrist2 and the Poljane Manuscript3 are mentioned in the present paper, while handwritten hymn books were particularly popular among the common people. These hymn books were preserved through the textual transmission in all of the regional varieties of the Slovenian standard language4 existing in the Slovenian ethnic territories until the unification of the Slovenian standard language in the mid-nineteenth century. They were either copied by scribes from earlier printed or handwritten hymn books, flyers for special occasions (e.g., pilgrimage, church consecration), lectionaries, catechisms and prayer books, or were written from memory, or dictation.

2It is precisely by supplying scholarly evidence and an explanation of its textual tradition that the critical edition should provide us with the most authentic and complete version of a literary work’s text: “When a text is transmitted through more than one witness, a critical edition will generally take a strong interest in recording the variant readings of some or all of those manuscripts or editions” (Burghart 2017).

3Therefore, in addition to the original text, the critical edition should also hand down a textual tradition of witnesses, which exists in the form of transcripts, fragments, drafts, proof sheets, etc. in order to clarify the process of the text’s transformation and genesis: “The apparatus is a set of notes designed to foster in the reader an awareness of the historical and editorial processes that resulted in the text he or she is reading and to give the reader what he or she needs to evaluate the editor’s decisions” (Damon 2017, 202). In principle, digital editions offer more possibilities than printed versions to present the text in its various formats, as they allow for the juxtaposition of different forms of text (for example, a digital facsimile and a diplomatic transcript) in a selected size category and in precisely selected places, at the level of the paragraph, the stanza or the verse (Ogrin 2005, 9-10).

4In the present paper, taking as an example the diplomatic transcript of a selected hymnal manuscript, we present the question of encoding the variant readings of the text as reflected in its handwritten and printed versions according to the TEI Guidelines from 2019. These can be used to produce a variety of digital texts, from simple reading editions to scholarly critical editions, dictionaries and language corpora. The digital markup means that the structural elements of the text (e.g., verses, stanzas, notes) are encoded with TEI-defined tags that the computer can then recognise. The TEI recommendations consist of descriptions of the tags rendered in the XML markup language, which can be defined as an open encoding standard focused not on the display but on the structure and internal relations of the data. We can use these tags to mark in the electronic encoding the desired structure and other characteristics of the text (Ogrin and Erjavec 2009; Ogrin 2005, 14; Hockey 2000, 24). In this way, we have, since 2004, prepared nine editions of the eZISS library – Digital Scholarly Editions of Slovenian Literature (Ogrin and Erjavec 2009).

5In the following paragraphs, we present Foglar’s Manuscript, the selected base text, in a diplomatic transcript, along with its variant readings in the preserved versions of the hymns in other manuscripts and prints. The diplomatic transcript is important not only for locating the original version of the text, but also for comparing versions on all levels of the language. By using suitable web tools, we can also study the stanza forms, verse and metre. In addition to a presentation of selected tools, we were interested in the different kinds of display of the digital diplomatic text in the HTML layout.

2. The Text Corpus

1Foglar’s hymn book (1757–1762) is a Slovenian Baroque manuscript containing twenty-four hymns. It originates in the area of the then Austrian province of Styria in the parish of Kamnica near Maribor. The manuscript is named after Lovrenc Foglar, one of its authors (cf. Ditmajer 2017), and contains the following hymn texts: the oldest Slovenian hymns celebrating the pilgrimage to Mariazell in Upper Styria; four hymns dedicated to saints; a festive hymn dedicated to the Holy Trinity; two hymns with eschatological content; one worshipping Jesus’ name; one of repentance for the fasting period; and another praising the love of God. During the examination of preserved Slovenian religious hymns known to date, as well as other witnesses containing hymn texts, a number of hymns were discovered that could have served as a base text for Foglar’s Manuscript, or vice versa.

2To date, we have included eight variant texts in the critical edition:

- the hymnal manuscript Pesmarica from Gorje (1761–1792, NRSS Ms 113),

- Paglovec’s hymnal manuscript Cantilenae variae partim antiquae partim (1733–1759, NUK R 0 75843),

- Lavrenčič’s printed Misijonske pesme inu molitve (1757, NUK GS 0 10212),

- Krebs’s hymnal manuscript (1750–1800, NRSS Ms 022),

- the hymnal manuscript Cerkvene pesmi in molitve (ok 1778, NRSS Ms 052),

- Maurer’s hymnal manuscript (1754, NUL Ms 1485),

- Parhamer’s printed catechism entitled Obchinzka knisicza zpitavanya teh pet glavnih stukov maloga katekizmussa (1764, UKM R 20675), and

- Manuskript iz Podmelca (1802–1810, Archives of the ZRC SAZU Institute of Ethnomusicology, Kokošar’s Series, Ms. II., Sg. Ms. Ko. 101/125).

3The selected variant hymns were mostly produced in the eighteenth century in the regions of Styria, Carinthia, Carniola and Gorizia. Eleven of the hymns exist in a single version (for example, Pesem od svete trojce, Pesem od božje lubezni, Pesem od svete Notburge), and only one exists in two versions (Pesem od Marije Magdalene). All of the manuscripts and prints mentioned are listed among the <listWit> (witness list) source list added to the preface to the critical edition, and shown as follows:

3. The Diplomatic Transcript of the Base Text and its Variations

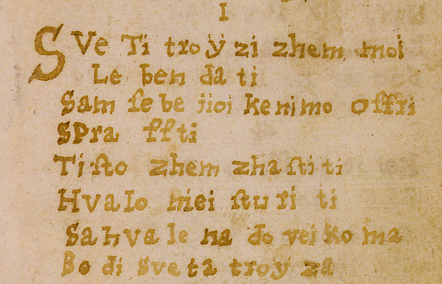

1In early Slovenian hymn books, one graphic line does not always correspond to a single metric verse. Frequently, due to a lack of paper space, scribes would write the next word or phrase on a second graphic line. In the diplomatic transcript, we used the TEI element <label> to number stanzas; verse lines encoded with an <l> (line) are embedded in an <lg> (line group) element following <label>; the refrain is nested in the parent stanza (i.e., <lg>)with an assigned type attribute; and the break of the verse line is simply marked with an <lb> (line break) element, as shown in the encoding example of the first stanza of Pesmi od Svete trojce:

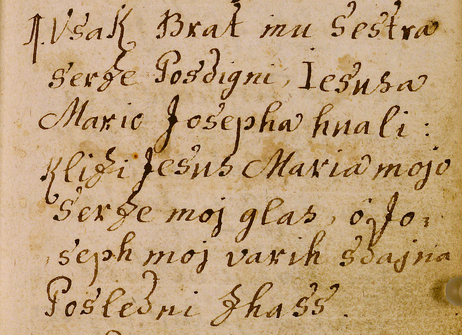

2Difficulties are caused above all by hymn texts in which the author has disregarded the verse line, rendering the hymn in prose form. In view of this, hymns with a second verse line continuing in the same graphic line where the first verse line begins were encoded with the <ab> (anonymous block) element, while the type attribute was used to mark the stanza, with line breaks indicated as shown in the following example:

3In addition to verse lines, stanzas and refrains, rhyme and foot can be specifically encoded in a machine readable format. However, this markup in our scholarly edition have not yet been taken into account. The rhyme patterns can be documented with the rhyme attribute, while the label attribute is used to specify which parts of a rhyme scheme a given set of rhyming words represent. The value of this attribute is usually one of the letters of the rhyme pattern.

4In the second example the met attribute indicates the metrical structure, where the symbol | marks the foot boundaries. If some lines divert from the metrical scheme documented in the met attribute, the deviation is documented with the real attribute:

5For a scholarly critical edition of a manuscript, especially one from an early period, it is essential to look for textual variants, as they facilitate the detection of errors in the overall text and aid the search for the base text. In the described critical edition, all of the preserved textual transmissions (traditions) are displayed and organised so as to be subordinate to the base text, that is, Foglar’s text. Our first attempt at encoding textual variance in poetic texts was the preparation of the digital critical edition of Anton Martin Slomšek’s poems, which was devised in the period 2006–2011 and is still in progress. The diplomatic transcript of Foglar’s hymn book was treated with the same apparatus criticus, applying the same parallel segmentation method5 and displaying the variant readings using the <app> element. The latter contains the base text (the lemma), and one or more variant readings encoded with the <rdg> (reading) element, each with a reference to the appropriate version via the witt (witness) attribute:

6The wit attribute value refers to the identifier of the description of manuscripts and prints with the aforementioned versions of hymnal texts, such as the value “M” for Maurerjeve pesmarice, or “POD” denoting the Manuskript iz Podmelca, as shown in the list of sources in the preceding section. The critical edition includes 988 units of the critical apparatus <app>, which contain 988 <lem> elements and 1072 <rdg> elements. Only pure textual variants were included as units of the critical apparatus, excluding the identification of the verse-stanza structure of the variant text.

7Particularly problematic are hymns whose entire stanzas, or simply the verses of a single stanza, are switched, such as in Pesem od vernih duš. Such switches can be more explicitly marked using the xml:id (identifier) and corresp (corresponds) attributes:

8In textual criticism, we distinguish two major groups of variant readings: substantive and accidental (Greg 1950). The latter include those changes that do not significantly affect the meaning, such as orthographic variants, although in some cases even these cause meaning-related dilemmas. The Baroque text of Foglar’s Manuscript is substantively marked by the non-standard use of spelling and the regional phonetic variation in various branches of the textual transmission. The scope of the critical apparatus and the degree of its granularity have been the subject of discussion in philology since the beginning of critical edition production, especially regarding the distinction between the level of purely orthographic differences, or so-called accidentals, and the level of more meaning-related differences, or so-called substantives, which go back to Greg’s theory of copy-text and beyond into the history of philology.6

9In order to provide a better visual representation of the various types of modification when applying tools for the display and analysis of texts, we need to classify these modifications more precisely and introduce more units of the critical apparatus within one verse line. In the eighteenth century – due to the lack of Slovenian textbooks on spelling and grammar, and of Slovenian books in general, as well as to the fact that school instruction was carried out in a foreign language (only elementary instruction was conducted in Slovenian) and that the education of copyists varied – the use of graphic characters for certain sounds varied significantly (marked in the critical edition with the type attribute value):

10Until the mid-nineteenth century, the Slovenian ethnic territories were characterised by the coexistence of regional varieties of the Slovenian standard language. We therefore encounter many phonological and morphological variant readings in this critical edition, which, like spelling variants, do not affect the meaning of a particular word.

11Lexical substitutions are of more importance, but in the manuscript texts included in the critical edition it is generally a case of synonyms:

4. Tools for Text Analysis and Display

1The XML-TEI encoding of textual variation shown above conveys the logical and semantic structure of the variant readings in the hymns, on the basis of which the editor of the critical edition is able to formulate his or her textological and philological analysis of the textual tradition of a given hymn in a machine readable format. However, this format is not intended for the reading public of the digital edition, that is, for actual reading from the screen. For this purpose, it has to be converted into a reader-friendly display format, such as HTML, where the meaning structure of the text is converted into the appropriate graphic design of the text.

2To show textual variance in the textual transmission of Foglar’s Manuscript, we used (or tested) three tools that have very different sets of functionalities for converting XML-TEI elements to the HTML format of display, and that are derived from very different concepts of the graphic representation of textual variants. Apart from these, Versioning Machine (VM)7 is the tool that probably has the longest history. Although it boasts plentiful functionalities, we did not opt for it in this case because we would have had to extensively adapt the XML format in order for the VM to display it well. The tools were evaluated according to how the relevant files, prepared in strict agreement with the TEI Guidelines, were converted without special adjustments.

5. XSLT Conversion

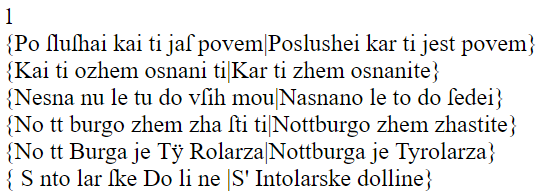

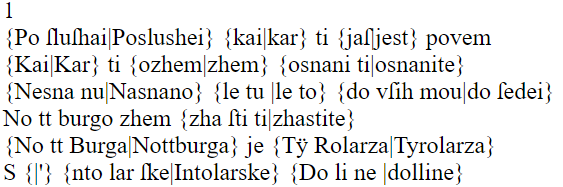

1During the preparation of the digital scholarly edition of Foglar’s hymn book, XSLT conversion was predominantly used, having been developed as a working tool for the emerging critical edition of the poems by A. M. Slomšek. A web-based tool8 supporting this conversion enables the conversion of documents from Word (.docx) into TEI and/or the conversion of TEI documents into HTML. For each conversion, a folder is created that is accessible online and contains both the source file and its converted TEI encoding, as well as the HTML file generated from it. The conversion works so that the general conversion of the TEI encoding (provided and continuously developed by the TEI Consortium) into its HTML version is enriched with local changes that the user can activate by selecting the appropriate profile. For our purposes, we developed a ZRC profile that upgrades the general conversion by placing the variant in braces {}, inside which first a lemma, then a variant reading are listed, separated by a vertical slash |. The name of the version referred to by wit/@witness is displayed when a user places a mouse hover over it.

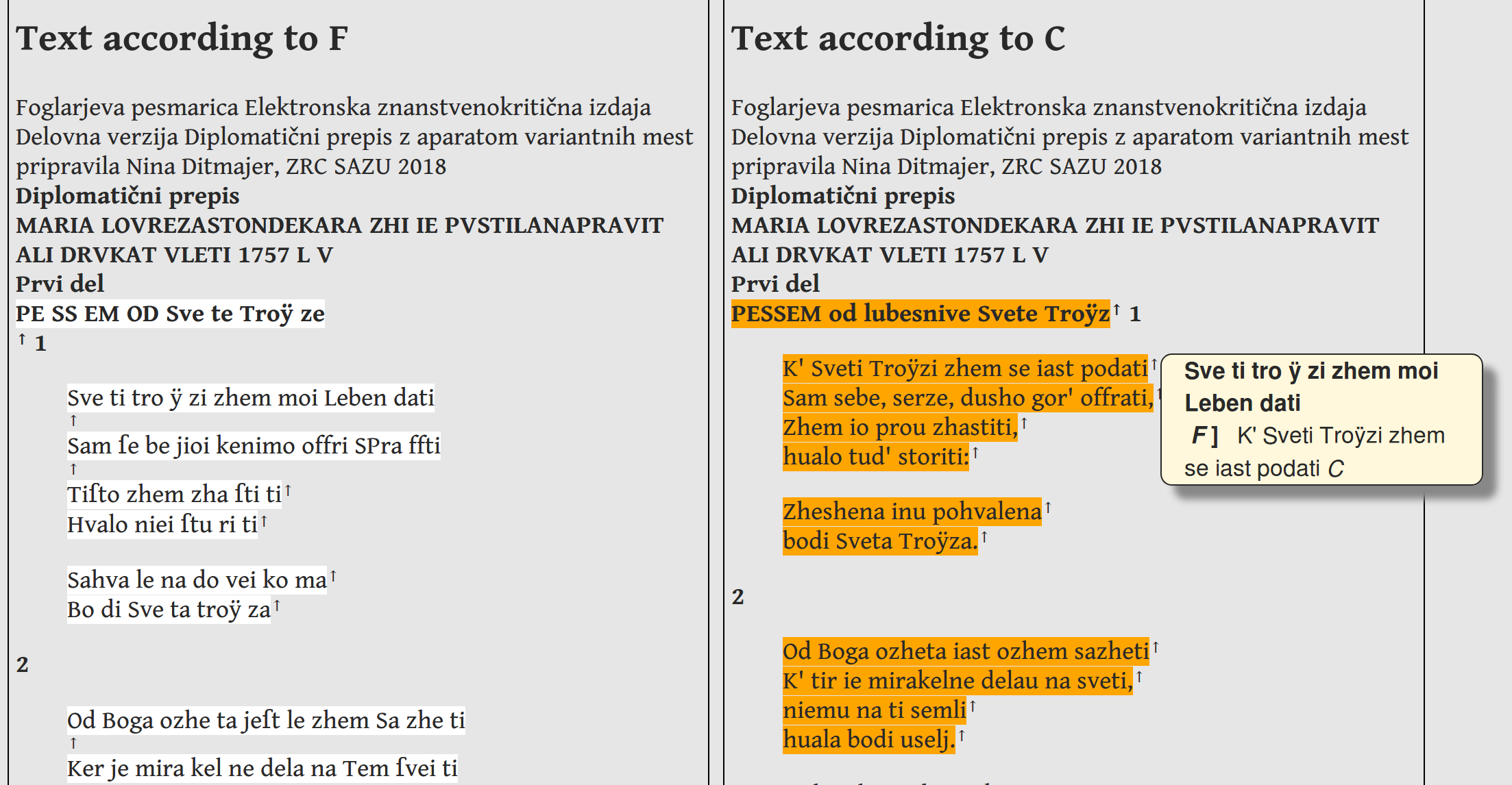

2The aforementioned issue of granularity of the critical apparatus, i.e., how detailed the information about individual variant readings should be (based either on words or larger sections), is clearly shown in Figures 3 and 4. First, Figure 3 shows the solution where the <lem> element contains the entire verse of Foglar’s text, followed by the <rdg> element containing the whole verse from the manuscript by Mihail Paglovec. In this case, the critical apparatus unit contains and defines the entire verse line as a variant reading. Figure 4, on the other hand, shows the same verse lines as Figure 3, but encoded in a way that each word is represented by its own unit, so each element containing a single word from Foglar’s text has a corresponding <rdg> element containing a single word from Paglovec’s text. Thus, all of the orthographic and substantive variants are likely to be more clearly shown, with the exception of the spaces between the syllables, which, although not so important for the analysis, does make reading somewhat more difficult.

3This tool, whose generic conversion according to the TEI Guidelines has been upgraded with a synoptic display of the critical apparatus in a main text line, is intended for a simple but philologically accurate presentation of textual variance in a digital scholarly edition. Its use is conditioned by the consistent adoption of the parallel segmentation method in TEI. Although not providing the reader with the greatest flexibility of display (for example, the ability to hide or display a specific version of the text), it is a valuable tool because it is available as an online service9 and can easily be installed on any computer, enabling it to be run at any time during the editorial process. It is ideal for displaying texts in which only two or three, perhaps four, versions are compared in each unit of the apparatus, which seems to be entirely appropriate for the actual range of textual variance established in the earlier Slovenian literary tradition.

6. TEI CAT

1The TEI Critical Apparatus Toolbox (TEI CAT) is a web service10 developed by a group led by Marjorie Burghart. It is explicitly intended for critical editors preparing digital scholarly editions with the parallel segmentation method under the TEI Guidelines. It therefore serves as a work aid enabling editors to check and visualise meaning components in the course of the preparation of their scholarly editions. Many functionalities are provided for this purpose, including those for checking errors and inconsistencies that emerge in the encoding process (Burghart 2016). We will focus on the functionalities that are the most relevant to our textual analyses.

2The user sends an XML file to the online service to verify the correctness of the tagging. If the results are positive, the main text or the so-called critical text of the edition will be displayed for viewing. Beside each unit of the critical apparatus, an arrow appears on screen, which can be clicked to open a window with the content of the unit in a classic form based on the use of the right square bracket: everything to the left of the square bracket represents the lemma, while to the right is the variant reading marked with the abbreviation of the variation.

3In addition, we are free to select a number of controls, such as whether the system should display page breaks or colour the units of the apparatus that do not contain all of the versions, or, conversely, whether it should colour only those units of the apparatus that contain a specific version, etc.

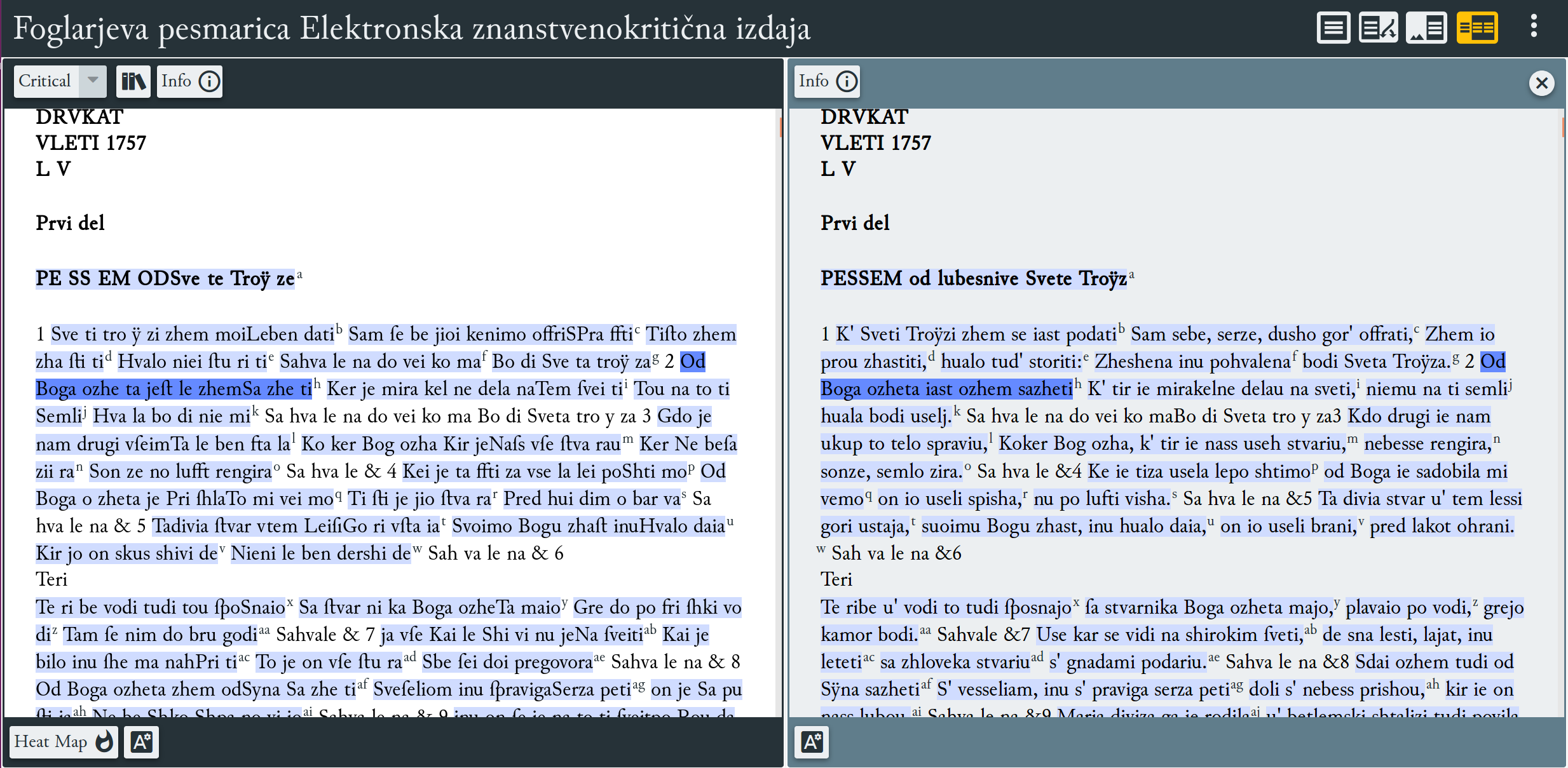

4The most important functionality offered by TEI CAT is a parallel view of all of the versions generated by the tool from the units of the critical apparatus. Regardless of the fact that, according to the TEI Guidelines, the recommended place for the list of versions <listWit> is in the so-called <teiHeader> metadata element, the CAT system will locate the <listWit> anywhere in the TEI document (in our case, it is placed in <back>), logically sorting its information with respect to the abbreviations. The user can then choose to view all of the versions in a parallel display, or, by ticking only the selected abbreviations, have individual versions displayed in parallel for comparison:

5The disadvantage of the parallel display in the TEI CAT tool is that, in longer texts, columns match only at the beginning of the file, while in the continuation the relationship can be broken, resulting in the reader losing reference for comparison. The tool cannot (yet) be downloaded to the user’s computer and run locally. It is in fact not primarily intended for preparing an edition as a publication for the general readership, but rather serves to allow verifications in the course of the editorial process. However, in addition to its being very practical for displaying the apparatus and several other functionalities, its greatest advantage is the basic statistical analysis that it produces of the document, not just of the TEI tags used, but also of the texts themselves: it generates a simple but informative frequency list of the words occurring in the edition, with any spelling variant being considered as a new word form, of course.

7. EVT

1Open source EVT – Edition Visualization Technology – is designed to produce and publish digital scholarly editions in TEI. As with TEI CAT, the encoding of the critical apparatus with the parallel segmentation method is required.11 A group led by Roberto Rosselli del Turco conceived EVT with the explicit aim of bridging the gap between the TEI Guidelines as a first-rate standard for the production of complex philological works, such as critical editions, and the problems that philologists face when they want their editions encoded in TEI visualised and published online (Rosselli del Turco 2014). Whether locally or online, EVT is opened and used as a web page in the selected browser. The tool is designed as a dynamic environment, with Javascript being used to upgrade HTML options. It offers a range of options for displaying critical texts and their variants, including a parallel version and various details about the particular units of the apparatus, which can be freely selected by switching between and generating various displays in real time (see Figure 6). Among the options that would be welcome for the type of editions contained in the eZISS library are support for the dynamic display of digital facsimiles, support for the designated entities and their lists, such as place and personal names, etc. (clearly, these must be appropriately encoded in TEI), and a high level of adaptability to specific project needs.

2The conception of the EVT tool is determined by the common conceptual world of Western European philology, whereby the critical editor normally choses to present the text of one selected manuscript accompanied by a smaller or larger number of versions of the same text presented in the form of a critical apparatus. This concept is based on a rich textual tradition composed of thousands of medieval manuscripts both in Latin and in various vernaculars. For example, the digital edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales prepared by Peter Robinson is based on a transcription of these stories in around 80 preserved manuscripts and incunabula. The Slovenian textual tradition is much less extensive: texts have been preserved in several versions only since the early modern era, while it is only from the eighteenth century onwards that the Slovenian literary tradition offers a significant increase in textual variance. Another large area extremely rich in variation is Slovenian folk poetry, which is not discussed here; nonetheless, EVT might be an ideal tool for studying the exceptional variation of Slovenian folk poetry.

3For the Slovenian manuscript culture to which Foglar’s Manuscript belongs, it is very often the case that only a single manuscript has survived of several witnesses of the text. In such situations, the rich textual tradition has only been passed down to us as one surviving manuscript, the so-called codex unicus. This becomes the sole object of a critical edition, which requires a meticulous and detailed presentation, in particular by distinguishing between its diplomatic and critical transcript, which is typical of a philology such as Slovenian philology. In the light of the above, the design of a quality and complex tool, such as EVT, should be appropriately adjusted to optimise the display of a parallel representation of a diplomatic and critical transcript of the same text (in some cases, it will involve critical apparatus, but unless at least two versions of the text have been preserved, the apparatus cannot be compiled).

4From this perspective, Foglar’s hymn book is a particularly demanding example. On the one hand, with eight previously recorded versions of textual transmission or tradition, it requires a classical Western European type of scholarly edition; on the other hand, a Slovenian philological type of scholarly edition is determined by the contrasting method involving the diplomatic and the critical transcript of the main text. In the future, this need should also be met by adjustments made to its reading display solutions.

8. Conclusion

1The article presents the method adopted to compile a critical apparatus of variant readings in the digital scholarly edition of Foglar’s Manuscript, a Slovenian Baroque hymn book from the mid-eighteenth century. The editor compared Foglar’s text with its versions in eight other manuscripts and old prints. The variant readings identified in the collation process were encoded with XML elements according to the TEI Guidelines as units of the critical apparatus. The problem of the variation of older poetic texts raises the problem that various tools embody various functionalities but no tool satisfies the needs of all researchers. This opens up (not entirely new) horizons, where the value of the canonical record of our edition in TEI is further increased, as it can be processed with various, ever evolving tools and according to various needs of presentation and research. Therefore, the first question that arose was how to label a maximum number of analytical findings about the variants using the TEI markup: how to indicate whether the differences are on the level of spelling, vocabulary, lexis, semantics, etc. The second question was how to best display variants of such diversity in the HTML format designed for reading from the screen. Taking into account the requirements of this critical edition, we tested and evaluated three tools for visualising the critical apparatus. In addition to technology-related differences and the diverse functionalities of these tools, their dependence on individual philological and manuscript traditions has also been shown. As well as the critical apparatus of variant readings, the Slovenian handwritten tradition requires support for the parallel presentation of a diplomatic transcript (with the apparatus) and a critical transcript intended for the wider reading public due to the significant orthographic differences between early and modern Slovenian. In further work we will continue to attempt to further bring the Slovene text tradition ever closer to an ideal method of displaying and publishing texts.

Sources and Literature

- Burghart, Marjorie. 2016. “The TEI Critical Apparatus Toolbox: Empowering Textual Scholars through Display, Control, and Comparison Features.” Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative 10 (2016). https://journals.openedition.org/jtei/1520#article-1520 .

- Burghart, Marjorie. 2017. “Textual Variants.” In Digital Editing of Medieval Texts: A Textbook. Edited by Marjorie Burghart.

- “Online course: Digital Scholarly Editions: Manuscripts, Texts, and TEI Encoding - Digital Editing of Medieval Manuscripts.” Digital Editing of Medieval Manuscripts.https://www.digitalmanuscripts.eu/digital-editing-of-medieval-texts-a-textbook/.

- Cankar, Izidor. 2007. S poti. Elektronska znanstvenokritična izdaja. Edited by Matija Ogrin, Luka Vidmar and Tomaž Erjavec. Elektronske znanstvenokritične izdaje slovenskega slovstva [Scholarly Digital Editions of Slovenian Literature], ZRC SAZU, IJS. http://nl.ijs.si/e-zrc/izidor/.

- Damon, Cynthia. 2016. “Beyond Variants: Some Digital Desiderata for the Critical Apparatus of Ancient Greek and Latin Texts.” In Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories and Practices , edited by Matthew James Driscoll and Elena Pierazzo, 201-18. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

- Ditmajer, Nina. 2017. “Romarske pesmi v Foglarjevi pesmarici (1757–1762).” In Rokopisi slovenskega slovstva od srednjega veka do moderne, edited by Aleksander Bjelčevič, Marija Ogrin and Urška Perenič, 75–82. Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete. http://centerslo.si/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Obdobja-36_Ditmajer.pdf.

- Ditmajer, Nina, and Matija Ogrin. 2018. “Foglarjeva pesmarica [Foglar’s Hymn Book]. Ms 123.” In Register slovenskih rokopisov 17. in 18. stoletja [Register of Baroque and Enlightenment Slovenian Manuscripts]. http://ezb.ijs.si/nrss/.

- Greg, W. W. 1950. “The Rationale of Copy-Text.” Studies in Bibliography 3: 19–36.

- Hockey, Susan. 2000. Electronic Texts in the Humanities . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ogrin, Matija. 2005. “Uvod. O znanstvenih izdajah in digitalni humanistiki.” In Znanstvene izdaje in elektronski medij , edited by Matija Ogrin, 7–21. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, ZRC SAZU.

- Ogrin, Matija, and Tomaž Erjavec. 2009. “Ekdotika in tehnologija: elektronske znanstvenokritične izdaje slovenskega slovstva.” Jezik in slovstvo 54, No. 6: 57–72.

- Ogrin, Matija, and Tomaž Erjavec. 2009. “Elektronske znanstvenokritične izdaje slovenskega slovstva eZISS: metode zapisa in izdaje.” Infrastruktura slovenščine in slovenistike, Simpozij Obdobja 28, edited by Marko Stabej, 123–28. Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete. http://www.centerslo.net/files/file/simpozij/simp28/Erjavec_Ogrin.pdf.

- Ogrin, Matija, and Andrejka Žejn. 2016. “Strojno podprta kolacija slovenskih rokopisnih besedil: variantna mesta v luči računalniških algoritmov in vizualizacij.” Zbornik konference Jezikovne tehnologije in digitalna humanistika , edited by Tomaž Erjavec and Darja Fišer, 125–32. Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete, Jožef Stefan Institute.

- “P5 Guidelines – TEI: Text Encoding Initiative.” TEI Consortium . http://www.tei-c.org/Guidelines/P5/.

- Rosselli Del Turco, Roberto, Giancarlo Buomprisco, Chiara Di Pietro, Julia Kenny, Raffaele Masotti, and Jacopo Pugliese. 2014. “Edition Visualization Technology: A Simple Tool to Visualize TEI-based Digital Editions.” Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative 8. https://journals.openedition.org/jtei/1077 .

- Sahle, Patrick. 2013. Digitale Editionsformen. Zum Umgang mit der Überlieferung unter den Bedingungen des Medienwandels. Teil 1: Das typografische Erbe. Norderstedt: BoD.

- TEI Consortium. 2018. TEI P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. Version 3.3.0. [31 Jan. 2018].

Nina Ditmajer, Matija Ogrin, Tomaž Erjavec

ENCODING TEXTUAL VARIANTS OF THE EARLY MODERN SLOVENIAN POETIC TEXTS IN TEI

SUMMARY

1In the process of textual transmission (Textüberlieferung), many textual variations appear in the text, which are called (variant) readings (Lesarten) or variants (Überlieferungsvarianten). The problem of textual variation in Slovenian literary history, which is particularly evident in numerous handwritten and printed hymn books, only appears in the early modern age, especially in the Baroque era. Hymnal texts were transmitted among the people both through oral and written traditions. In the present paper, taking as an example the diplomatic transcript of Foglar’s hymn book, we present the question of encoding the variant readings of this hymnal text as reflected in its handwritten and printed versions according to the TEI Guidelines from 2019. The TEI recommendations consist of descriptions of the tags rendered in the currently most widely used XML markup language. We present Foglar’s Manuscript, the selected base text, whose diplomatic transcript contains a critical apparatus of its variant readings located in the other eight preserved hymn books originating in the four historical Slovenian regions. We first highlight examples of the diplomatic transcript of verse lines, differentiating between the graphic and the verse line. Various elements and attributes can be added for the machine analysis of the text, such as an analysis of stanzas and feet. We then present ways of encoding variant readings, using the parallel segmentation method and focusing on verse line switches within stanzas and on substantive and accidental variants. Considering the fact that Slovenian literary texts were significantly marked by the regional varieties of the standard language prior to its unification in the mid-nineteenth century, including by an orthographic heterogeneity, we decided to introduce a number of units of the critical apparatus within a verse line and assign each variant reading an type attribute value. In the final section, we present three tools for text analysis and display: our own XSLT conversion tool, the TEI Critical Apparatus Toolbox and the open source Edition Visualization Technology tool. For the critical edition in question, XSLT conversion, which generates a static web site with a visually separate display of the variant readings in a line, turned out to be reasonably appropriate. The TEI CAT tool provides a very useful parallel display of the variants, but is not intended for final publication.

2Generally distinguished by powerful functionalities, the EVT tool should be slightly adjusted for the Slovenian textual tradition, in which the diplomatic and critical transcripts of the same text play the major role. Future technological solutions for digital scholarly editions will have to take into account, in particular, the diverse, complex differences in the structure of both transcripts: the diplomatic transcript, for example, with its specific problems is encoded and shown as a paragraph in which several interventions have taken place; the critical transcript, on the other hand, can display the same text in linguistically regularised forms, as a stanza of rhymed verse with a marked metric structure, etc. The parallel representation of the digital facsimile and two methodologically completely different transcriptions (and possibly even a classical critical apparatus) potentially represents a significant technological problem; however, only such an ecdotic (text-critical) conception of the scholarly critical edition can reveal all of the semantic wealth of early modern Slovenian texts.

Nina Ditmajer, Matija Ogrin, Tomaž Erjavec

ZAPIS VARIANTNOSTI STAREJŠIH SLOVENSKIH PESNIŠKIH BESEDIL V TEI

POVZETEK

1V procesu rokopisne preoddaje (Textüberlieferung, Textual transmission) nastajajo v besedilu številne razlike, ki jih imenujemo variante (Lesarten, readings) ali variantna mesta (Überlieferungsvarianten, variants). V slovenski literarni zgodovini se problem variantnosti pojavi še posebej v dobi baroka, ta pa je najbolj vidna v številnih rokopisnih in tiskanih pesmaricah, ki so se med ljudstvom širile tako pisno kot ustno.

2V prispevku na primeru diplomatičnega prepisa Foglarjeve pesmarice prikazujemo problematiko zapisa variantnih mest istega besedila v preostalih rokopisnih in tiskanih verzijah po Smernicah TEI (TEI Consortium 2019). Priporočila TEI sestavljajo opisne razlage teh oznak, ki so izražene v trenutno najbolj razširjenem računalniškem označevalnem jeziku (markup language) XML. Foglarjev rokopis je v naši izdaji prepoznan kot temeljno besedilo (base text), ki smo mu v diplomatičnem prepisu dodali kritični aparat variantnih mest, najdenih v osmih drugih pesmaricah iz štirih slovenskih historičnih pokrajin. Najprej prikazujemo primere diplomatičnega zapisa verza z razlikovanjem med grafično in verzno vrstico. Za strojno analizo besedila lahko zapisu dodajamo različne oznake in atribute, npr. za analizo rime in stopice. Nato z uporabo metode vzporednega segmentiranja variantnih mest (parallel segmentation method) prikazujemo primer zapisa variantnih mest. Še posebej se osredotočamo na označevanje zamenjav verzov v kitici ter substancialnih in akcidentalnih variantnih mest. Ker so slovenska besedila pred poenotenjem slovenskega knjižnega jezika precej pokrajinsko obarvana in izkazujejo tudi neenoten pravopis, smo poskusili znotraj enega verza uvesti več enot kritičnega aparata in variante označiti z vrednostjo atributa type. Na koncu smo predstavili in preizkusili tri orodja za prikaz in analizo besedil: našo lastno pretvorbo XSLT, orodje TEI Critical Apparatus Toolbox in odprtokodno orodje Edition Visualization Technology. Kot razmeroma primerna se je za našo izdajo izkazala pretvorba XSLT, ki izdela statično spletno stran z vizualno ločenim izpisom variantnih mest v vrstici. Orodje TEI CAT omogoča zelo uporaben vzporedni prikaz variantnih mest, vendar ni namenjeno končnemu publiciranju. Orodje EVT bi bilo potrebno ob že razvitih zmogljivih funkcionalnostih nekoliko prilagoditi za slovensko besedilno izročilo, kjer imata največjo vlogo diplomatični in kritični prepis istega besedila. Bodoče tehnološke rešitve elektronskih znanstvenokritičnih izdaj bodo morale upoštevati zlasti raznolike, kompleksne razlike v strukturi obeh prepisov: diplomatični prepis je denimo s svojimi specifičnimi problemi označen in prikazan kot odstavek, v katerega je posegalo več rok ipd.; kritični prepis pa lahko prikazuje isto besedilo v jezikoslovno regulariziranih oblikah, kot kitico rimanih verzov z označeno metrično strukturo itn. Vzporedni prikaz digitalnega faksimila in dveh metodološko povsem različnih prepisov (in eventualno še klasičnega kritičnega aparata) potencialno predstavlja nemajhne tehnološke probleme; vendar šele takšna ekdotična (tekstnokritična) zasnova edicije razpre vse semantično bogastvo starejših slovenskih besedil.

* Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Novi trg 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, nina.ditmajer@zrc-sazu.si

** Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Novi trg 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, matija.ogrin@zrc-sazu.si

*** Department of Knowledge Technologies, Jožef Stefan Institute, Jamova Cesta 39, SI-1000 Ljubljana, tomaz.erjavec@ijs.si

1. The text is treated in the Register of Baroque and Enlightenment Slovenian Manuscripts (NRSS Ms 124).

2. Cf. the Register of Baroque and Enlightenment Slovenian Manuscripts (NRSS Ms 15, Ms 17, Ms 24, Ms 71).

3. Cf. the Register of Baroque and Enlightenment Slovenian Manuscripts (NRSS Ms 23, Ms 28).

4. The Eastern Slovenian standard language with its Prekmurje and Eastern Styrian varieties and the Central Slovenian standard language with its Carniolan and Carinthian varieties.

5. For a detailed description of the method, see section “12.2 Linking the Apparatus to the Text” of the TEI Guidelines, 12 Critical Apparatus - The TEI Guidelines, https://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/TC.html.

6. For a comprehensive historical outline of the views that have been formed in textual criticism with regard to this question, see Sahle (2013, 172-73).

7. Cf. Versioning Machine 5.0, http://v-machine.org/.

8. DOCX to TEI to HTML conversion, http://nl.ijs.si/tei/convert/.

9. The conversion service operates at the address http://nl.ijs.si/tei/convert/, by selecting the conversion profile ZRC.

10. The consortium developing the tool includes CNRS and the University of Lyon, cf. TEI Critical Apparatus Toolbox, http://teicat.huma-num.fr/index.php.

11. The EVT tool is freely available for download to a personal computer and is easy to install.