Debating Evil: Using Word Embeddings to Analyse Parliamentary Debates on War Criminals in the Netherlands

UDC:003.295:342.537.6:355.012(492)"1940/1945"

IZVLEČEK

Razprave o zlu: analiziranje parlamentarnih razprav o vojnih zločincih na Nizozemskem z vektorskimi vložitvami besed

1Predstavljamo metodo za raziskovanje sprememb v zgodovinskem diskurzu, pri kateri se uporabljajo obsežni besedilni korpusi in modeli vektorske vložitve besed. Kot študijo primera raziskujemo razprave o kaznovanju vojnih zločincev v nizozemskem parlamentu v obdobju 1935–1975. Predstavili bomo, kako se za sledenje zgodovinskega razvoja parlamentarnega besedišča skozi čas lahko uporabljajo modeli vektorske vložitve besed, ki se učijo z Googlovim algoritmom Word2Vec.

2Ključne besede: vojni zločinci, zgodovina kaznovanja, parlamentarna zgodovina, Word2Vec, modeli vektorske vložitve besed

ABSTRACT

1We are proposing a method to investigate changes in historical discourse by using large bodies of text and word embedding models. As a case study, we investigate discussions in Dutch Parliament about the punishment of war criminals in the period 1945-1975. We will demonstrate how word embedding models, trained with Google’s Word2Vec algorithm, can be used to trace historical developments in parliamentary vocabulary through time.

2Keywords: War Criminals, Penal History, Parliamentary History, Word2Vec, Word Embedding Models

1. The Case: War Criminals

1Soon after German forces in the Netherlands surrendered in May of 1945, the question arose how the hundreds of suspected war criminals and thousands of Nazi collaborators in Dutch custody were to be treated. For the next five decades, this question caused a series of heated political controversies. The debates in Dutch parliament about the punishment, penalty reduction, or release of these people are not only among the longest debates in Dutch parliamentary history, but are generally considered to have been the most emotionally charged (Bootsma and Griensven 2003; Futselaar 2015; Tames 2013).

1.1. Discourse and Controversy

1In this paper, we use an implementation of word embedding models (WEMs) to analyse parliamentary discussions concerning incarcerated war criminals and Nazi collaborators after the end of the German occupation. At peak, in the summer of 1945, more than a hundred thousand people were incarcerated. They were accused of a variety of crimes, all committed during the occupation of the country: political and military collaboration, war crimes, and (complicity in) genocide. The majority of these prisoners were civilians, whose crimes amounted to little more than membership of national socialist organisations. These people, and other small fry, were released quickly. A small and dwindling number of serious offenders remained in prison, some of them until 1989. After the 1960s, all remaining prisoners were former German officials and officers, whose initial death sentences had been commuted to life in prison. These prisoners became the flashpoint of intense political and media attention. As long as they remained behind bars, plans for their release continued to resurface, and cause political controversy (Piersma 2005; Tames 2013; Futselaar 2015; Grevers 2013).

2The main medium of parliamentary communication is spoken language. We aim to demonstrate that a systematic investigation of the verbatim records of the language used in Dutch parliament to discuss these cases can reveal historical change. The results will enable us to track the vocabularies in these discussions through time. We assume that this vocabulary, as we will call it, reflects the changing parliamentary discourse about incarcerated war criminals in Dutch society. We aim to link these developments in parliamentary vocabulary to actual historical events, developments concerning the post-war dealing with war criminals, and discursive shifts in Dutch society (Olieman et al. 2017). Specifically, we aim to investigate the changing political attitude towards incarcerated war criminals and use our findings to test established notions prevalent in Dutch historiography.

3The published proceedings of the two houses of parliament provide us with a dataset comprising of all the words spoken in the plenary sessions. The completeness of the parliamentary dataset allows us to investigate the changing parliamentary vocabulary through time, and in the context of different discussions.

4We here focus on two questions directly related to the treatment of these delinquents in the Dutch penal system. The first of these concerns the focus on the identification of the wronged party: did politicians focus on crimes against the Dutch nation as a whole, or against specific groups of individual victims? The second concerns the appropriateness of harsh punishments, specifically whether or not life imprisonment was considered a just alternative for the death penalty. These questions both derive directly from historiography and serve to answer an overarching question: can we assess the validity of traditional scholarship using unsupervised text mining?

2. Parliamentary Proceedings

1In this investigation, we rely entirely on parliamentary proceedings, known in Dutch as the Handelingen der Staten-Generaal. The Handelingen are available in machine-readable form. The minutes of both houses of parliament for the period 1814-1995 were first digitised by the Royal Library of the Netherlands and made available to the public in 2010. The dataset was dramatically improved in the PoliticalMashUp project that ran from 2012 to 2016. This improved and enriched dataset is freely available, on request, from DANS, the Dutch national repository of research data. The dataset consists of a large collection of XML files containing the complete minutes of all the meetings of the lower and upper chambers of parliament, separated by date, speaker, political affiliation, etc. This makes it an excellent corpus for various forms of automated text analysis (Marx et al. 2012).

3. Word Embedding Models and Historical Research

1We investigate the vocabularies used in parliament to discuss a broad category of inmates that could be described as political delinquents, as well as the changes of these vocabularies through time. This is a fairly normal investigation to undertake in traditional historical research - that is to say without computational analyses. Historians typically work by reading the relevant texts. This enables them to use and expand their domain knowledge while processing the data. Although this hermeneutic step is inevitably part of historical research, this approach has several disadvantages. In this particular case the corpus to be assessed is enormous, making reading and manual encoding of text problematic. More importantly, the traditional research process is highly vulnerable to the biases of the reader/researcher. When studying ethically charged controversies in the relatively recent past, this vulnerability to bias is evidently problematic. People with an interest in recent history and knowledge of the Dutch language almost inevitably hold an opinion on these issues and on the actors in the debate. How do we ensure that our personal political preferences do not influence our reading of the source materials?

3.1. Words in Vector Space

1A WEM provides a possible solution to these problems. WEMs are techniques to investigate words, and relations between words, in large text corpora. WEMs are based on the calculation of the average distance of unique words to all other unique words in a corpus. The position of each unique word can then be described as a list of numerical values, representing its distance to all other unique words. This list of values is called the ‘vector’ of the word. In principle, the number of values, also referred to as ‘coordinates’, or ‘dimensions’ of the vector, is the same as the number of unique words in the text, minus one. The complete trained corpus, or ‘spatial model’, is often referred to as a vector space. The method does not prioritize any particular words; the position of each unique word is investigated and given a vector in the model.

2The vectors of words within a corpus can be compared. That is to say, the closeness of one vector to another can be calculated. High closeness often reflects a close semantic relationship. Some words with similar vectors are synonyms or near synonyms, or have very similar usages (tea and coffee, for example). Here, we use cosine similarity to calculate the closeness of vectors, although other methods are also feasible.

3Since the position of unique words relative to other words is an average calculated on the basis of all occurrences in the text, WEMs are exceptionally effective at investigating relations between relatively frequent words in a sufficiently large text corpus. For historical research, insight in these relations is very useful, and goes far beyond mere closeness. With WEMs we are able to identify associations between words that are not self-evident and would not have been found by traditional means (Schmidt 2015).

3.2. Limitations of WEMs

1WEMs also have an important downside that is particularly relevant to historical research. Since the training of the model determines the position of a word relative to all other words in that specific corpus, its vector is meaningless in any other model. Word vectors, hence, can only be compared with other word vectors within the same spatial model. For historians, this means that comparisons between different moments in time are difficult. To make a comparison through time it would be necessary to divide the corpus into subsets representing different periods. For each of these period-specific corpora, a new model, based on a subset of the corpus, needs to be trained. Since vectors of different WEMs are not readily comparable, change through time is difficult to investigate with WEMs. This means that, while WEMs are perfectly adequate tools for fulfilling the first of our aims, investigating vocabularies, they are virtually useless for the second aim, investigating change through time. Since change through time is the core of virtually all historical research (including this investigation), this presents us with a major problem; how can we compare outcomes for different WEMs, for different periods in time?

2We have, however, developed a workaround to enable us to use WEMs to investigate changing ways to talk about certain topics through time. We do not directly compare the closeness of vectors within different models, but we calculate relative closeness of vectors for the same terms within different models by using cosine similarity.

3.3. Word2Vec

1For this investigation, we have used the relatively popular Word2Vec implementation of WEMs to train and analyse word embedding models. Word2Vec was developed by a team of Google engineers and published in 2013. It has been shown to be a particularly effective implementation. This algorithm, however, was developed with a different aim than the one for which we are using it. Initially, Word2Vec was a tool to investigate natural language itself, for example to identify (near) synonyms. In our, historical, investigation, the statistical modelling of language as such is not the objective. Rather than trying to identify linguistic regularities to investigate language, we focus on linguistic irregularities and patterns to identify the influence of political and historical change on the language used in political speech.

2For researchers using the R programming language, a package is readily available to analyse texts. This package, created and maintained by Benjamin Schmidt, has been used in this investigation as well (Schmidt 2015, 2017). Our method, however, is in no way dependent on this particular platform and could also be used in Python or any other environment. Neither is the method reliant on the Word2Vec algorithm. It would work broadly in the same way with another implementation of word embeddings. Here, however, we have chosen to use a popular WEM implementation in a relatively user friendly and accessible environment, with the added benefit of using open-source, free software.

4. Analytical Process

1Text analysis with WEMs involves two necessary steps. The first of these, the training of the corpus, creates the spatial model, the WEM itself. The second step is the analysis of the positions of specific words or word clusters within the virtual space of the model.

2The corpus of the Handelingen is vast by the standards of historical research (millions of words per year), but not very large for the kind of analysis we are undertaking. For the purpose of WEMs, the size is barely adequate. Therefore we have trained our dataset with a Skip-GramWord2Vec model, which has anecdotally been shown to yield better results on smaller samples (Gelbukh 2015). The vectors of different words can be compared within the model by using cosine similarity. Within a vector space, any two vectors by can be described, by definition, as lying within a horizontal plane. Cosine similarity calculates the angle between these vectors. Perfectly overlapping vectors would result in a cosine similarity of 1, a perfectly opposite relationship -1. In practice, WEMs consist only of positive space, which means that scores fall between 0 (low, or no similarity) and 1 (high, or perfect) similarity (Singhal 2001).

4.1. Training the Models

1The first step of our workaround is to train two WEMs (more than two is equally feasible), based on two subsets of the corpus (in this case 1945-1955 and 1965-1975). Each of these subsets contains ten years of parliamentary speeches. When using this approach, it is necessary to use relatively similar training corpora, both in terms of size and in terms of language use. For historical research into relatively short periods of parliamentary history, this is not particularly problematic. For reasons of efficiency, we have limited ourselves to unique words that appear at least five times in the corpus and we have limited the number of dimensions of each vector to one hundred. This allows this investigation to be undertaken, and repeated, using fairly normal office grade hardware. We have experimented with more dimensions (several hundreds), but more vectors appear only to be useful with larger corpora. Training WEMs with several hundreds of dimensions also requires far more computational power.

4.2. Analysing Word Vectors

1Within each spatial model, we have identified the 250 words with the highest cosine similarity to the Dutch terms for ‘war criminal’ (singular and plural, see Table 1). With these 250 nearest neighbours, we have defined the time specific vocabulary used in the discussion of war criminals. Obviously, these are not the same 250 words in each model. To identify changes in the discussions surrounding our topic, we calculated the cosine similarity of each of the 250 nearest-neighbour words in each model to two different terms that are present in each of the two corpora. This allows us to compare the position of the vocabulary of the discussion on our topic (war criminals) in relation to, in this case, two stable concepts. The selection of these concepts is crucial for our investigation and for this method. It is here that we translate our research question into a formal, computational inquiry.

2For now, we have chosen a two-dimensional implementation of this technique. This is not theoretically necessary, but it allows us to visualize and analyse results more easily in two dimensions. What is important is that concepts used to investigate the relative position of each investigated word are the same in each of the models to be compared. It is also necessary that the concepts are relatively stable through time. Since concepts are represented by words in the corpus itself, words that shift meaning dramatically, such as the English word ‘gay’, are less suitable than ‘cheerful’ or ‘homosexual’, which have not undergone such dramatic change over time.

3When discussing concepts, the number of possible words referring to the same concept is often greater than one. Since our investigation focuses on concepts that may be described with multiple words, we need to create a so-called combined vector. We used synonyms and plurals to create a cluster of words with the shared meaning of the concept of interest. This cluster was used as a combined vector in the model by calculating the mean of all the vectors of the cluster words. That is to say that this word set was treated as a single term, resulting in a vector of similar length to a single-word vector. This combined vector allows us to investigate our corpus using all synonyms and near-synonyms of terms as if they were a single term, with a single vector.

| Concept | Concept represented by combined vector of the Dutch words: |

|---|---|

| Death penalty | ‘doodstraf’ and ‘doodstraffen’ |

| Life imprisonment | ‘levenslang’, ‘levenslange’, ‘vrijheidsstraf’, ‘gevangenisstraffen’, ‘gevangenisstraf’, ‘opsluiting’, and ‘hechtenis’ |

| Treason/traitor | ‘landverrader’, ‘landverraders’, ‘verrader’, ‘verraders’, and ‘landverraad’ |

| Victim | ‘slachtoffer’ and ‘slachtoffers’ |

| War Criminal | ‘oorlogsmisdadiger’ and ‘oorlogsmisdadigers’ |

4After selecting two concepts that are present in each of the two corpora, we can calculate the relative similarity of other terms in the corpus to each of them. Although vectors between the two trained WEMs are not comparable, the relative distance to two or more other vectors can be compared very well across several models, provided the underlying concepts are historically stable. When the terms used to estimate the relative position of vocabularies are related and dissimilar, or even perfectly opposite, a historically meaningful analysis becomes viable.

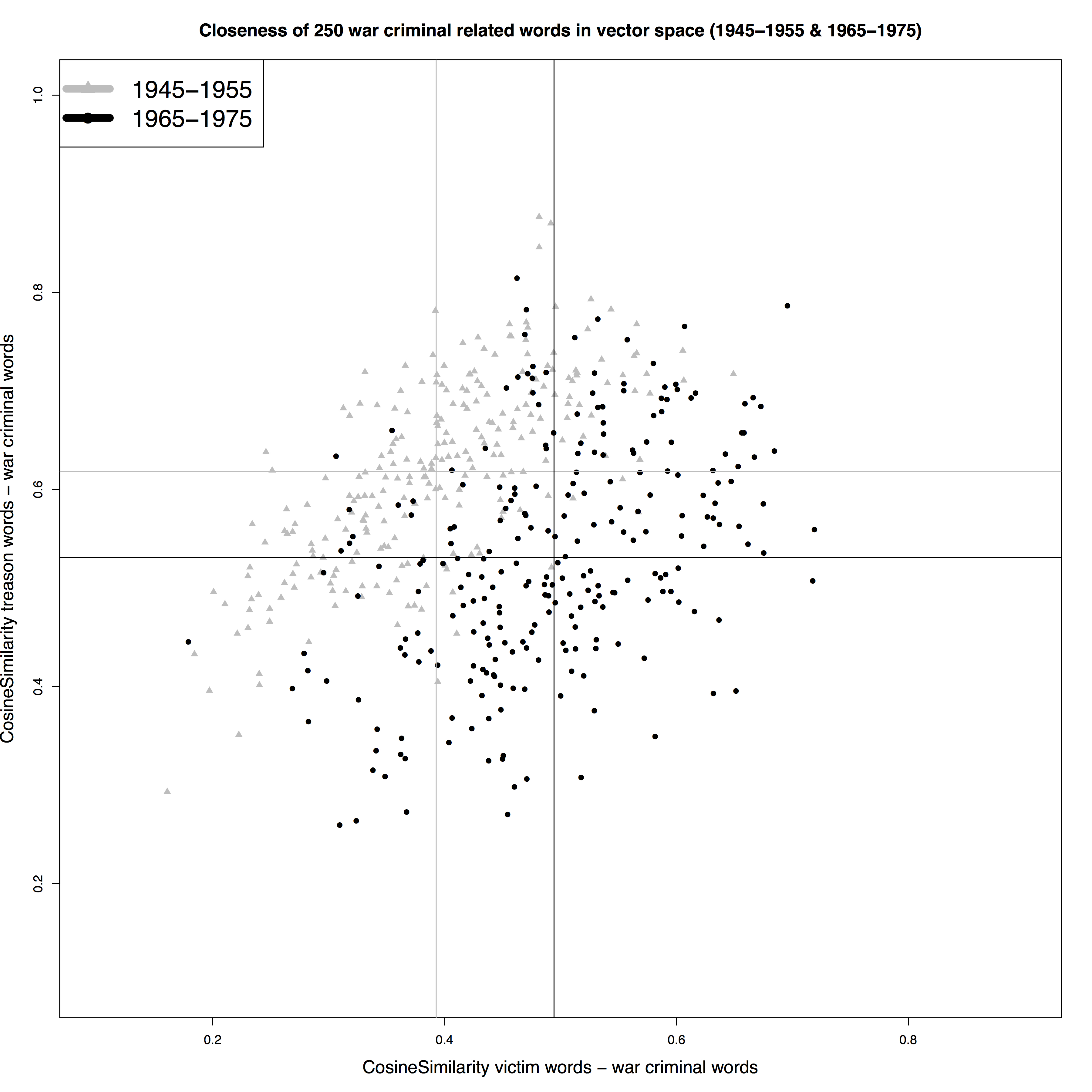

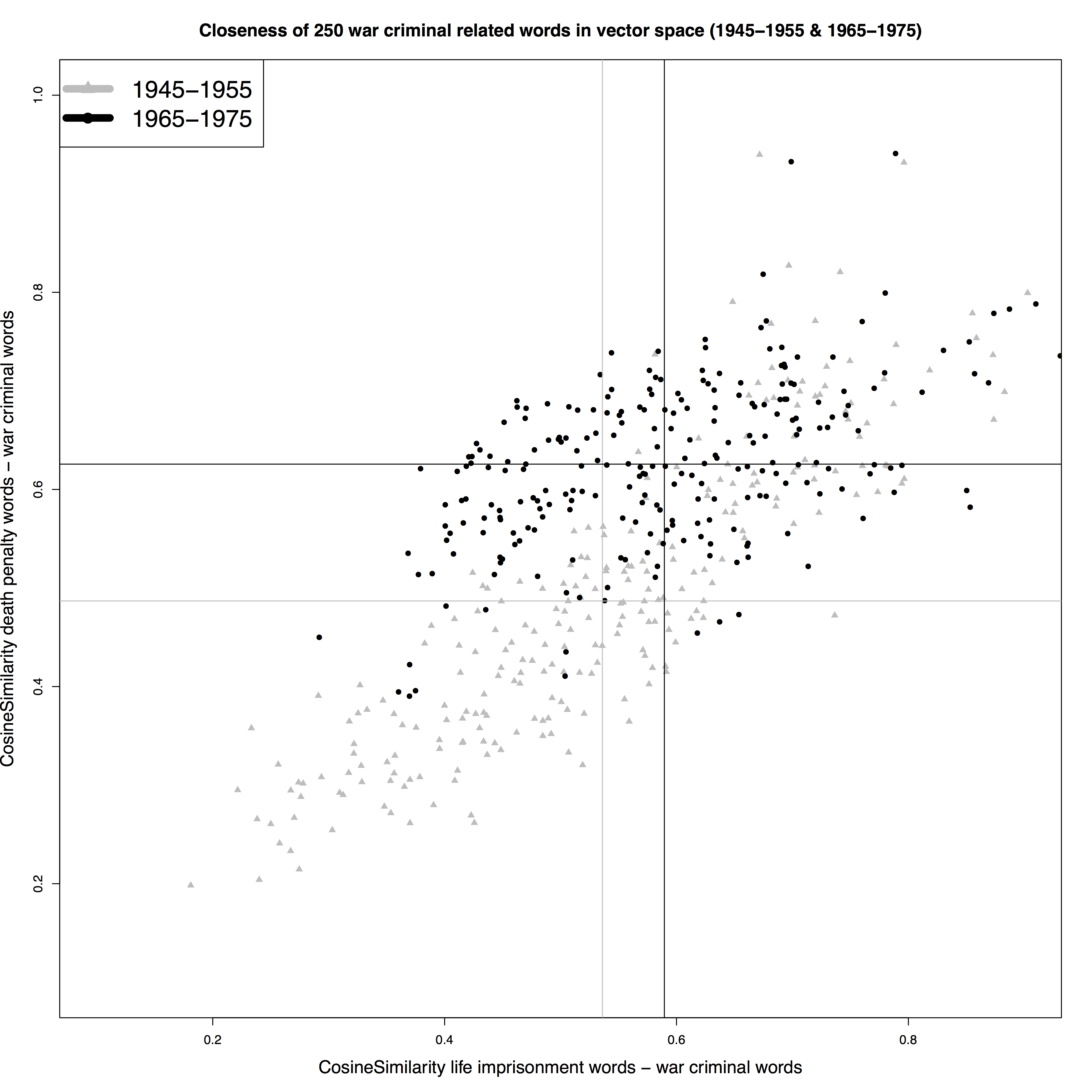

5Using two concepts allows us to plot our ‘vocabulary’, that is the top 250 war-criminal-related words in each of the two periods, in a two-dimensional space. Figure 1 and 2 show the similarity scores of each of the 250 word vocabularies relative to one concept that serves as the y-axis, and another on the x-axis. Each point represents one of the 250 words that form the war-criminal vocabulary for a specific time period. They are plotted based on their cosine similarity score to the combined vector of the concept ‘victim’ (x) and ‘treason’ (y) in Figure 1, and to ‘life imprisonment’ (x) and ‘death penalty’ (y) in Figure 2. The average scores of all 250 war criminal words on the two dimensions are shown as horizontal and vertical lines. Thus, we have arrived at a visual representation that allows for a comparison of word embedding results for more than one corpus and hence for a comparison through time (in this case, between two distinct historical periods).

5. Results

1Here, we present only two examples using four concepts and two time periods (1945-1955 and 1965-1975). Specifically, we try to identify differences in the way incarcerated war criminals and collaborators were discussed in the immediate aftermath of the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, and at the height of controversies surrounding the intended release of a number of German war criminals from Dutch prisons - namely Kotälla, Aus der Fünten, and Fischer (Piersma 2005).

2Obviously, the discussions in the two periods refer to different groups of perpetrators. In the immediate aftermath of the Nazi occupation the population of inmates was large and diverse, consisting of small-time war profiteers, minor collaborators and their families, but also mass murderers. In the second period, only a handful of elderly foreigners were left, whose crimes were relatively similar and also similarly egregious.

3For this investigation, however, our primary aim is not to unearth radically new insights into post-war penal policy in the Netherlands, but to confront the results of an unsupervised, ’distant’ reading of parliamentary records to an established historiography. Such a historiography is available for the case at hand; Dutch historians have identified a number of trends in the thinking about political delinquents that (if true) should be reflected in these discussions. Two changes have been identified in particular:

- A turn in focus from the nature of the crime committed and the person of the perpetrator towards the lasting, psychological damage endured by the victims (Heijden 2012; Haan 1997).

- A decline in the support, both public and political, for harsh, vengeful punishments, exemplified here in the discussions about the propriety of the death penalty. Although the death penalty was (again) abolished in the 1950s, it remained a point of discussion with regard to war criminals in custody (Futselaar 2015; Smits 2008).

5.1. Historical Case

1Over the course of three decades, attitudes to incarcerated war criminals, as represented by the vocabularies used to discuss them, changed. In the first period the emphasis lay on crimes against the collective, whereas the focus shifted more towards the plight of individual victims. As can be seen in Figure 1, the initial emphasis on crimes against the nation (treason) in debates about war criminals declined. The average cosine similarity between war-criminal words and treason words (horizontal lines) decreased significantly when we compare 1945-1955 to 1965-1975. At the same time, we observed increased levels of closeness in vector space between war criminal related words to words associated with (individual) victims, as can be seen in Figure 1.

2At first glance, this observation is completely in line with the relevant historiography. Several authors have emphasized the sharp rise of interest into the mental health of individual war victims and their families as a decisive factor in policy making and the formation of political opinion. Figure 1 also indicates the observed shift in discourse from focusing on the initial crimes, committed by the war criminals, to the consequences of their deeds for individual people involved (Haan 1997; Heijden 2012; Smits 2008; Withuis 2002).

3This development can, however, not be considered a mere discursive change: the observed shifts in parliamentary vocabulary represent actual historical developments in the post-war dealing with war criminals. In the early 1970s, the only war criminals remaining in Dutch prisons were German nationals. Whereas in 1945, main part of the more than hundred thousand incarcerated war criminals were Dutch citizens. Evidently, the accusation of treason was only applicable to the latter group. Hence, if we compare the two periods, it is not surprising that the discursive element of ‘treason’ decreased in importance in the war criminal vocabulary in Dutch parliamentary debates between 1965 and 1975.

4Although the shifts in vocabulary indicate that there was an observable shift in discourse, we have to stress that our analysis also indicates continuity in the parliamentary vocabulary of 1945-1955 and 1965-1975. The scatterplots in Figure 1 indicate a shift, but do not show a complete turn of the parliamentary vocabulary on war criminals. The scatterplots in Figure 1 from both periods show overlap between the nearest neighbours of war criminal related words from 1945-1955 and 1965-1975, scored on closeness to both treason and victim words. We have observed a significant change, or shift. However, we also have to conclude that we did not find a complete turn in vocabulary, as our analysis also indicates continuity and a lasting importance for perpetration and treason in the war criminal debates.

5It remains imperative to remain aware of the possible pitfalls of this type of investigation. This is evident in the sharp rise of references to the death penalty in war criminal vocabulary that we observed (see Figure 2). During the second period under scrutiny, capital punishment had long been discontinued in the Netherlands and could not have been discussed as a serious penal option. Closer scrutiny of the data revealed that in many discussions, capital punishment was not advocated, but merely used as a reference point. The war criminals in question had originally been condemned to die, but their punishment had been commuted into life imprisonment. Several members of parliament felt that a pardon would mean that the original verdict (death penalty) would be watered down twice. In these discussions, capital punishment was often referenced, even when its application was not a viable (or even legal) option (Futselaar 2015).

6. Conclusion

1This paper outlines a method for studying discursive changes in history. We trained WEMs and calculated cosine similarities between two opposite or related concepts for specific periods. This enabled us to compare WEMs for different periods. This opens the door for the use of word embeddings as a tool for historical research, because it enables us to investigate change through time in sufficiently large and consistent historical textual datasets. Parliamentary records are perhaps the best example of such datasets. This method holds considerable promise because parliamentary proceedings and other historical sources are increasingly digitised and made available in machine-readable form.

2We have shown how developments in vocabulary can be considered reflective of discursive changes. These changes are related to historical events and developments in the post-war dealing with war criminals in Dutch society. Recent historiography has suggested a dramatic shift away from the crime committed by war criminals and towards the consequences of these deeds for victims and their relatives. We do recognize that victims became more prominent in discussions about war criminals, but this did not diminish the importance of the deed they committed. In other words, the shift is there, but it appears to be far less radical then suggested.

3We could also demonstrate that actual historical developments regarding the type of war criminals incarcerated in the Netherlands (from many local convicts, to a handful of foreigners) were reflected by a discursive shift, in which closeness to ‘treason’ declined. German officials, in the eyes of post-war Dutch parliamentarians, did not commit treason by committing crimes against the Dutch nation.

4We have also encountered examples of pitfalls of an overly enthusiastic reliance on word embeddings as an analytical tool. Capital punishment was mentioned particularly frequently in the 1970s, but not because the possibility of executing the war criminals was seriously entertained. Distributional semantics are a powerful new tool for historians, but they do not remove the need for hermeneutic awareness. In this paper, the method is itself the main object of inquiry. We believe we have shown that it possible, feasible, and useful to develop and implement a coherent and widely applicable method for investigating historical change using WEMs.

7. Discussion

7.1. Method Evaluation

1For this paper, we have used two corpora, each representing ten years of parliamentary debate to train our WEMs. More interesting, from a research perspective, would be to find out how stable our results are when using smaller, overlapping windows of corpora over time, say with one year steps. It is likely (but not certain) that using more fine-grained windows will reveal similar developments and shifts in language use over time. Repeating the analysis with more data points has the potential to gain more insights in the graduality and the pace of the observed shifts in language used. That said, there is a potential trade-of between detail and precision given that the corpora available to historians are mostly modest in size.

2A second ambition is to look more seriously into the distribution of the cosine similarity scores, and the changes in these distributions over time. It will be interesting to measure, visualise, and statistically evaluate these distributions more closely, and to see whether they can be linked to, for example, unanimity and/or homogeneity in parliamentary discussions.

7.2. Historical Evaluation

1Another remaining ambition is to compare the parliamentary vocabularies used to discuss ‘domestic’ collaborators and foreign (usually German) war criminals. Furthermore, we also hope to position the war criminal debates in a broader context: how distinct are they from other war related debates, and from other discussions about penal law or criminals in a more general sense? Just as a closer investigation of different categories of perpetrators is viable and useful, different groups of war victims who were discussed in parliamentary debates also license further investigation. These may have included first and second generation victims of wartime violence and persecution, former forced labourers, holocaust survivors and the children of holocaust victims, etc. Given the emphasis on the protection of war victims mentioned above, we are interested to see if there have been changes in the groups emphasized in political debate about the topic.

7.3. Acknowledgements

1We are grateful to the participants of our Text Mining workshop at the Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C2DH) in Esch-sur-Alzette (June 2018), for their comments, input, and criticism. We would also like to thank the participants and organisers of the Language Technologies and Digital Humanities Conference in Ljubljana (September 2018).

Sources and Literature

Datasets and Academic Software:

- Van Lange, Milan. 2019. Debating Evil. Distributed by Github. https://github.com/MilanvanL/debating_evil.

- Marx, M., J. Van Doornik, A. Nusselder, and L. Buitinck. 2012. “Thematic collection: PoliticalMashup and Dutch Parliamentary Proceedings 1814-2013.” Distributed by Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS). https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-zg8-9x2v.

- Schmidt, Benjamin. 2017. “Bmschmidt/WordVectors: Tools for Creating and Analyzing Vector-Space Models of Texts Version 2.0 from GitHub.” GitHub. Accessed on November 5, 2017. https://rdrr.io/github/bmschmidt/wordVectors/.

- Wickham, Stefan Milton Bache and Hadley. 2014. Magrittr: A Forward-Pipe Operator for R (version 1.5). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=magrittr.

Literature:

- Bootsma, Peter, and Peter van Griensven. 2003. “‘Teleurstelling Is Mijn Opperste Emotie’: Vragen over Emotie in de Politiek Aan A.A.M. van Agt.” In Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis, 2003. Emotie in de Politiek, edited by Carla van Baalen, Willem Breedveid, Jan Willem Brouwer, Peter van Griensven, Jan Ramakers, and Inke Secker, 121 – 25. Den Haag: SDU Uitgevers.

- Futselaar, Ralf. 2015. Gevangenissen in oorlogstijd: 1940-1945. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Boom.

- Gelbukh, Alexander. 2015. Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 16th International Conference, CICLing 2015, Cairo, Egypt, April 14-20, 2015, Proceedings. Springer.

- Grevers, Helen. 2013. Van landverraders tot goede vaderlanders: de opsluiting van collaborateurs in Nederland en België, 1944-1950. Amsterdam: Balans.

- Haan, Ido de. 1997. Na de ondergang: de herinnering aan de Jodenvervolging in Nederland 1945-1995. Den Haag: SDU.

- Heijden, Chris van der. 2012. Dat nooit meer: de nasleep van de Tweede Wereldoorlog in Nederland. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Atlas Contact.

- Olieman, Alex, Kaspar Beelen, Milan van Lange, Jaap Kamps, and Maarten Marx. 2017. “Good Applications for Crummy Entity Linkers? The Case of Corpus Selection in Digital Humanities.” CoRR abs/1708.01162. http://arxiv.org/abs/1708.01162.

- Piersma, Hinke. 2005. De Drie van Breda: Duitse Oorlogsmisdadigers in Nederlandse Gevangenschap, 1945-1989. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Balans.

- Schmidt, Benjamin. 2015. “Vector Space Models for the Digital Humanities.” Ben’s Bookworm Blog. Accessed October 25, 2015. http://bookworm.benschmidt.org/posts/2015-10-25-Word-Embeddings.html.

- Singhal, Amit. 2001. “Modern Information Retrieval: A Brief Overview.” Bulletin of the IEEE Computer Society Technical Committee on Data Engineering 24: 9.

- Smits, Hans. 2008. Strafrechthervormers en hemelbestormers: opkomst en teloorgang van de Coornhert-Liga. Amsterdam: Aksant.

- Tames, Ismee. 2013. Doorn in het vlees: foute Nederlanders in de jaren vijftig en zestig. Erfenissen van Collaboratie. Amsterdam: Balans.

- Withuis, Jolande. 2002. Erkenning: van oorlogstrauma naar klaagcultuur. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

Milan M. van Lange, Ralf Futselaar

DEBATING EVIL: Using Word Embeddings to Analyse Parliamentary Debates on War Criminals in the Netherlands

SUMMARY

1This paper presents a case study to investigate the application of text mining techniques in historical research. We demonstrate the usability, advantages, and limitations of distributional semantics when investigating large diachronic historical datasets with word embedding models (WEMs). WEMs are applied to a large digitised and machine-readable historical dataset, namely the verbatim proceedings of both houses of Dutch parliament for the period 1945-1975.

2WEMs are techniques to investigate relations between words in large corpora. WEMs are based on the calculation of the average distance of unique words to all other unique words in a corpus. The position of each unique word can then be described as a list of numerical values, representing its distance to all other words. This list of values is called the ‘vector’ of the word. These numerical vectors can be compared. That is to say, the closeness of one vector to another can be calculated. High closeness often reflects a close semantic relationship between words. Some words with similar vectors are (near) synonyms or have very similar usages (tea and coffee, for example). For historical research insight in these relations is very useful. It goes far beyond mere closeness. With WEMs we are able to identify associations between words that are not self-evident and would not have been found by traditional means.

3The paper uses WEMs to investigate a case study on the vocabulary in parliamentary discussions concerning the punishment, incarceration, and release of Nazi collaborators and war criminals in the Netherlands. We identify changes related to historical events and developments in the post-war dealing with war criminals. Recent historiography on the topic has suggested a dramatic shift away from the crime committed by war criminals and towards the consequences of these deeds for victims and their relatives. We focus on two questions directly related to the treatment of these delinquents in the Dutch penal system. The first of these concerns the focus on the identification of the wronged party: did politicians focus on crimes against the Dutch nation as a whole, or against specific groups of individual victims? The second concerns the appropriateness of harsh punishments, specifically whether or not life imprisonment was considered a just alternative for the death penalty. These questions both derive directly from historiography and serve to answer an overarching question: can we assess the validity of traditional scholarship using text mining?

4In the paper we show how victims became more prominent in discussions about war criminals. This did, however, not diminish the importance of the deed they committed. In other words, the shift is there, but it appears to be far less radical then suggested. We also demonstrate that actual historical developments regarding the type of war criminals incarcerated in the Netherlands (from many local convicts in 1945, to a handful of foreigners in the 1970s) were reflected by a discursive shift in the debates. This paper also shows examples of pitfalls of an overly enthusiastic reliance on WEMs as an analytical tool in historical research. Capital punishment was mentioned particularly frequently in the debates of the 1970s, but not because MPs discussed the actual possibility of executing the war criminals.

5To conclude: distributional semantics are a powerful new tool for historians, but they do not remove the need for hermeneutic awareness. In this paper, the method is itself the main object of inquiry. We believe we have shown that it possible, feasible, and useful to develop and implement a coherent and widely applicable method for investigating historical change using WEMs. We believe that the outcomes of this investigation show that WEMs can be a useful and powerful tool in historical research, provided they are used cautiously and with sufficient domain knowledge.

Milan M. van Lange, Ralf Futselaar

RAZPRAVE O ZLU: ANALIZIRANJE PARLAMENTARNIH RAZPRAV O VOJNIH ZLOČINCIH NA NIZOZEMSKEM Z VEKTORSKIMI VLOŽITVAMI BESED

Povzetek

1V prispevku je prikazana študija primera, pri kateri se proučuje uporaba metod za rudarjenje besedil v zgodovinskih raziskavah. Predstavljamo uporabnost, prednosti in omejitve distribucijske semantike pri proučevanju obsežnih diahronih zgodovinskih podatkovnih nizov z modeli vektorske vložitve besed ( word embedding models – modeli WEM). Modele WEM smo uporabili za analizo obsežnih digitaliziranih in strojno berljivih zgodovinskih podatkovnih nizov, in sicer dobesednih zapisov postopkov v obeh domovih nizozemskega parlamenta v obdobju 1945–1975.

2Modeli WEM so metode za proučevanje povezav med besedami v obsežnih korupusih. Temeljijo na izračunu povprečne oddaljenosti edinstvenih besed od vseh drugih edinstvenih besed v korpusu. Položaj vsake edinstvene besede se potem lahko opiše kot seznam numeričnih vrednosti, ki predstavlja njeno oddaljenost od vseh drugih besed. Seznam vrednosti se imenuje "vektor" besede. Te numerične vektorje je mogoče primerjati. To pomeni, da je mogoče izračunati, kako blizu so si posamezni vektorji. Če so si zelo blizu, to pogosto pomen, da so besede tesno semantično povezane. Nekatere besede s podobnimi vektorji so (skoraj) sopomenke ali imajo zelo podobno rabo (na primer čaj in kava). Vpogled v te povezave je zelo koristen za zgodovinske raziskave in presega samo vprašanje bližine. Z modeli WEM lahko prepoznamo povezave med besedami, ki niso očitne in jih ne bi bilo mogoče najti na tradicionalne načine.

3V prispevku smo uporabili modele WEM za proučitev študije primera besedišča iz parlamentarnih razprav o kaznovanju, zaporni kazni in izpustitvi nacističnih kolaborantov in vojnih zločincev na Nizozemskem. Ugotavljali smo spremembe, povezane z zgodovinskimi dogodki in dogajanjem v povojni obravnavi vojnih zločincev. V novejšem zgodovinopisju, posvečenem tej tematiki, lahko opazimo precejšen premik od zločinov, ki so jih zagrešili vojnih zločinci, k posledicam teh dejanj za žrtve in njihove sorodnike. Osredotočili smo se na dve vprašanji, ki sta neposredno povezani z obravnavo teh zločincev v nizozemskem sistemu kazenskega pregona. Prvo vprašanje je povezano z osredotočanjem na opredelitev žrtev: ali so se politiki osredotočali na zločine proti nizozemskemu narodu kot celoti ali proti posameznim skupinam individualnih žrtev? Drugo vprašanje zadeva ustreznost strogih kazni, zlasti ali je dosmrtna zaporna kazen veljala za pravično alternativo smrtni kazni. Obe vprašanji izhajata neposredno iz zgodovinopisja in omogočata odgovor na širše vprašanje: ali lahko presojamo tehtnost tradicionalne znanosti z rudarjenjem besedil?

4V prispevku smo pokazali, kako lahko žrtve dobijo pomembnejše mesto v razpravah o vojnih zločincih. S tem pa se ni zmanjšal pomen dejanj, ki so jih zločinci zagrešili. Povedano drugače, premik je mogoče opaziti, vendar se zdi, da je precej manjši od pričakovanega. Pokazali smo tudi, da so se dejanski zgodovinski dogodki, povezani z vojnimi zločinci, ki so bili na Nizozemskem kaznovani z zaporom (od številnih lokalnih obsojencev leta 1945 do nekaj tujcev v sedemdesetih letih 20. stoletja), izrazili v diskurzivnem premiku v razpravah. V prispevku so prikazani tudi primeri različnih pasti, ki jih prinese preveč navdušeno opiranje na modele WEM kot analitično orodje v zgodovinskih raziskavah. Smrtna kazen se je pogosto omenjala predvsem v razpravah v sedemdesetih letih 20. stoletja, vendar ne zato, ker bi poslanci razpravljali o dejanski možnosti usmrtitve vojnih zločincev.

5Zaključimo lahko, da je distribucijska semantika koristno novo orodje za zgodovinarje, vendar to ne pomeni, da hermenevtična zavest ni več potrebna. V tem prispevku je glavni predmet proučevanja sama metoda. Menimo, da smo dokazali, da je mogoče, izvedljivo in koristno razviti in uporabljati usklajeno ter za široko rabo primerno metodo za proučevanje zgodovinskih sprememb z modeli WEM. Verjamemo, da rezultati te raziskave dokazujejo, da so modeli WEM lahko koristno in uporabno orodje v zgodovinskih raziskavah, če jih uporabljamo previdno in z ustreznim znanjem.

* NIOD, Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Herengracht 380, 1016CJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands, m.van.lange@niod.knaw.nl

** NIOD, Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Herengracht 380, 1016CJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands, r.futselaar@niod.knaw.nl