Irredentist Actions of the Slovenian Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists (the ORJUNA) in Italy and Austria (1922-1930)

UDC: 327.35(436+450=163.6)"1918/1941"

IZVLEČEK

IREDENTISTIČNE AKCIJE SLOVENSKE ORGANIZACIJE JUGOSLOVANSKIH NACIONALISTOV (ORJUNE) V ITALIJI IN AVSTRIJI (1922–1930)

1V prispevku so na podlagi razpoložljivega gradiva iz Arhiva Republike Slovenije, Hrvaškega državnega arhiva ter strateških načrtov in projektov, objavljenih v tiskovinah Organizacije jugoslovanskih nacionalistov (Orjune), predstavljena idejna načela, na katerih so temeljili ekspanzionistični načrti te organizacije. Posebna pozornost je posvečena iredentističnim akcijam, ki jih je slovenska veje Orjune opravila na ozemlju Italije (Trst, Gorica in Istra) in Avstrije (Koroška). Podrobno so opisana tudi idejna načela in metode dela organizacij Orjunavit (Organizacija jugoslovanskih nacionalistov v Italiji) in Fantovska zveza, ki sta Orjuni služili kot orodje za delovanje na ozemlju Italije in Avstrije. Ekspanzionistične ideje, ki so bile del Orjuninega ideološkega konstrukta in so se manifestirale z iredentističnimi akcijami na ozemlju sosednjih držav, so bile globoko ukoreninjene v temeljnih ideoloških načelih tega gibanja in posebnih zgodovinskih okoliščinah, v katerih je nastalo. Orjunini ideologi so svoje ekspanzionistične načrte o ustanovitvi Velike Jugoslavije, ki bi segala od Varne do Trsta in od Szegeda do Soluna, predstavljali kot boj za ustanovitev enotnega in celovitega etničnega telesa Južnih Slovanov. Vodstvo Orjune je na podlagi imperativa ohranitve etnične identitete slovenskega prebivalstva v obmejnih italijanskih in avstrijskih pokrajinah zagovarjalo sistematično uporabo organiziranega nasilja kot osnovnega orodja v boju za uresničitev svojih ciljev. Zmerna in legitimno usmerjena uradna zunanja politika jugoslovanskih oblasti ter oboroženi odpor uradnih varnostnih sil in paravojaških organizacij Italije in Avstrije sta vodstvu Orjune preprečila, da bi s terorizmom doseglo svoje zunanjepolitične cilje. Po drugi strani pa so se ekspanzionistične ideje, ki so bile ena od glavnih značilnosti ideologije Orjune, v medvojnem obdobju ohranile kot del idejnih konceptov vseh skrajnih desničarskih gibanj za jugoslovanski integralizem, ki so z manjšimi ali večjimi spremembami sprejela idejne konstrukte Organizacije jugoslovanskih nacionalistov.

2Ključne besede: ekspanzionizem, Orjunavit Slovenija, Organizacija jugoslovanskih nacionalistov, Trst, Istra, Koroška, Fantovska zveza, Marko Kranjec

ABSTRACT

1This paper aims to examine and analyse the documentation available in the Slovenian Historical Archives and the Croatian State Archives as well as the strategic plans and projects described on the pages of the ORJUNA printed pamphlets and bulletins in order to determine the ideological tenets that formed the basis of the foreign policy as conceived by the Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists (the ORJUNA). The focus of this paper will be on the irredentist actions taken by the Slovenian branch of the ORJUNA, carried out in the territories of Italy (Trieste, Gorizia, and Istria) and Austria (Carinthia). Special attention will be paid to the ORJUNAVIT (Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists in Italy) and Fantovska zveza (Slovenian Boys Union) organisations, which were effectively the instruments of the ORJUNA, carrying out its activities in the territories of Italy and Austria. The expansionist ideas that were part of the ORJUNA ideological constructs and their implementation, as manifested through irredentist actions carried out in the territory of Yugoslavia’s neighbouring countries, were firmly rooted in the fundamental ideological foundations of this movement and the specific historical circumstances in which it emerged. The ORJUNA ideologists presented their expansionist agenda to create a Greater Yugoslavia, extending over a vast territory from Varna to Trieste and from Szeged to Thessaloniki, as the ultimate result of the struggle to create a unified and all-encompassing ethnic body of South Slavs. Guided by the imperative of preserving the ethnic identity of the Slovenian population in the provinces bordering on Italy and Austria, the ORJUNA leadership promoted the systematic use of organised violence as the basic tool in the struggle to achieve its goals. Due to the restrained and legitimately-oriented official foreign policy of the Yugoslav governments, as well as in light of the armed resistance of the Italian and Austrian official security forces and paramilitaries, the leadership of the ORJUNA failed to achieve its foreign-political goals through the use of terror. On the other hand, the expansionist ideas that were one of the essential tenets of the ORJUNA’s ideology remained a part of the ideological concepts embraced by all far-right movements for the Yugoslav integralism in the interwar period, which, with slight modifications, adopted the ideological constructs advocated by the ORJUNA.

2Keywords: expansionism, ORJUNAVIT Slovenia, Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists, Trieste, Istria, Carinthia, Fantovska zveza, Marko Kranjec

1.

1The Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists (the ORJUNA)1 was established on 23 March 1921 in Split. Its founders came from the pre-war Yugoslav Nationalist Youth, which was an umbrella organisation that brought together ideologically rather diverse groups, associations, and individuals that advocated the idea of an integral Yugoslav nation. The ORJUNA was created at the time when the newly-established Yugoslav state was facing many challenges, ranging from the territorial pretensions of its neighbours, separatist movements, and conflicts between the proponents of the centralist concept and those who favoured federalism. The ORJUNA organisation was conceived as a bulwark of national and state Unitarianism, keeper of territorial integrity, and champion of the Yugoslav ethnic population, which had, in the wake of the Treaty of Versailles, found itself outside the borders that demarcated the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. 2 Guided by these principles and resorting to solutions offered by the ideologically similar movements from abroad (the Italian Fascism and German National Socialism), the ORJUNA leadership formulated a singular ideological system and devised a specific political practice that had no paragon in the Yugoslav region. In the period between 1921 and 1923, the ORJUNA established a number of affiliates throughout the territory of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The movement had its strongholds mostly in Dalmatia, Slovenia, and Vojvodina, while its organisational units in Croatia, Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbia were less developed.3 The movement was organised through committees, established on the local and regional level. The organisation was headed by the Central/Chief Committee, whereas the role of its executive body was assigned to its Directorate, which consisted of seven members and had its head office in Split. The president of the Central Committee was simultaneously the head of the Directorate and the leader of the entire movement. Due to a number of circumstances, such organisational structure was never fully implemented. In reality, heads of regional (provincial) committees acted independently, on their own, paying little concern to the instructions given by the Central Committee and the Directorate. The most eminent figure in the ORJUNA was Ljubo Leontić, who was the president of the Directorate in the period from 1923 to 1927, and who was more a symbol of its unity than effectively its leader.4 After 1925, due to the turbulent historical events that occurred in the political arena and conflicts within the organisation itself, the process of the ORJUNA’s gradual disintegration began to take place. The altered internal political context, pressures from the government, and conflicts between the Directorate and heads of the local committees resulted in a severe loss of membership and dissolution of a significant number of the movement’s local branches. After Ljubo Leontić left the ORJUNA in 1927, the movement underwent organisational restructuring. The General Secretariat was therefore established, headed by Miodrag Dimitrijević, while the headquarters of the movement were moved to Belgrade. 5 In the 1927–1929 period, the new leadership failed to impose its authority over the other strongholds of the movement (in Slovenia, Belgrade, and Southern Serbia). Hence, when the January 6 th Decree was promulgated and the Yugoslav parliamentarism was suspended, the ORJUNA found itself unprepared and subject to profound ideological and organisational confusion. Even though the royal dictatorial regime abolished all political organisations (paradoxically, it also quashed the ORJUNA, which was the only political organisation that espoused the ideology of Yugoslav integralism), the remaining cells of the ORJUNA organisation continued to be active in the early 1930s. They mostly carried out irredentist and terrorist actions, disguising themselves as legal organisations such as the National Defence and establishing new political groups and organisations. In 1929, these ORJUNA cells in the territory of Slovenia were brought together within the Association of Fighters of Yugoslavia,6 whereas the ORJUNA members from Dalmatia, Slavonia, and Serbia continued their activities within the Yugoslav Action movement.7

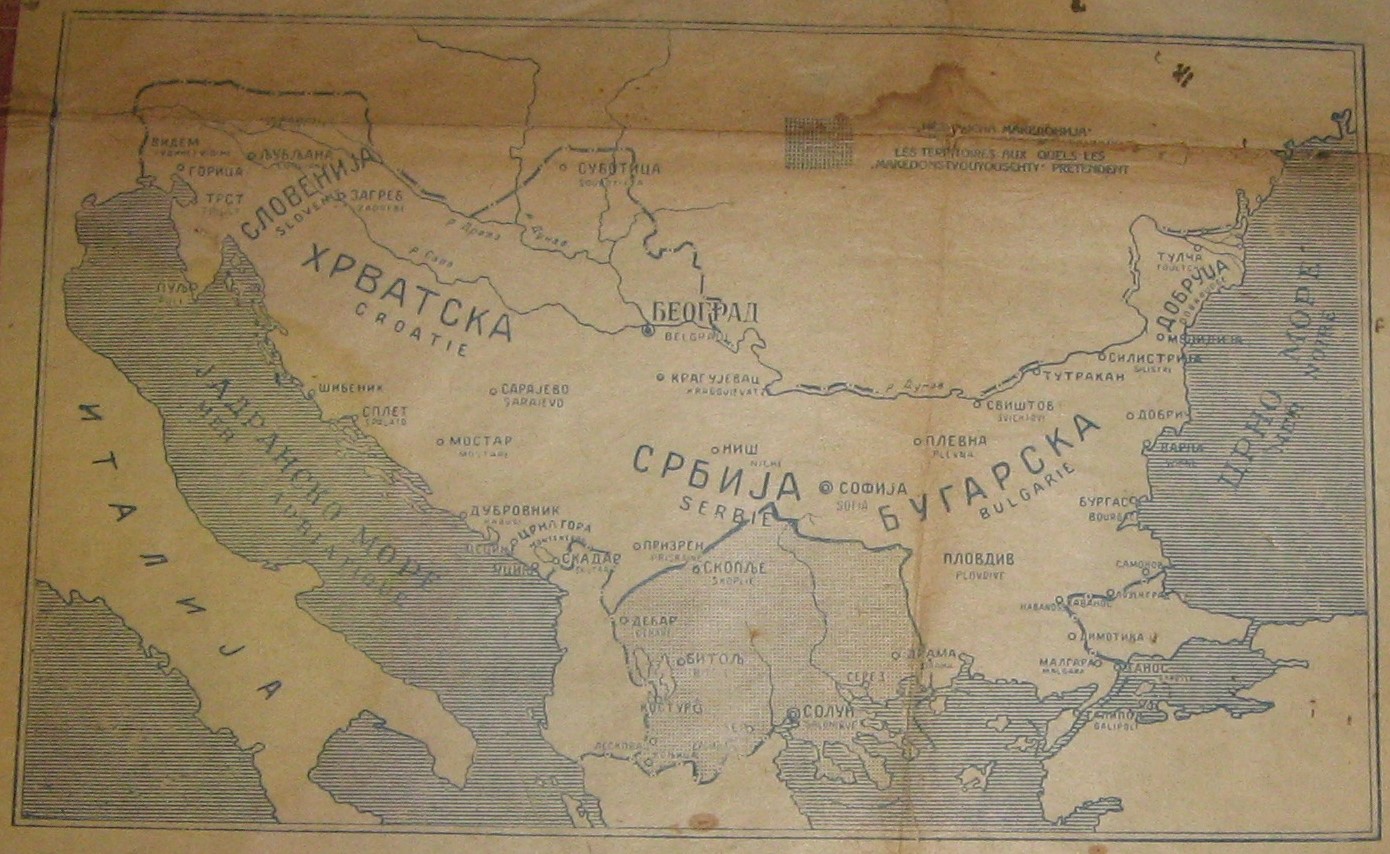

2The expansionist ideas that were part of the ORJUNA ideological construct and their implementation, as manifested through the irredentist actions carried out in the territory of Yugoslavia’s neighbouring countries, were firmly rooted in the fundamental notions from the ideology of this movement and the specific historical circumstances in which this movement came into being. Claiming that it was the direct heir of the political legacy of the Yugoslav Nationalist Youth (JNO), the ORJUNA saw itself as the torchbearer in the struggle of all Yugoslavs who strived for national independence. Given that during World War I, the Yugoslavs, led by Serbia and Montenegro, together with their allies, actively participated in the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the ideologists of the ORJUNA movement expected that the Entente Powers would allow the creation of the Yugoslav state, which would include all the territories populated by South Slavs. The provisions of the Versailles Peace Treaty were a major disappointment for the ORJUNA ideologists who – disregarding the fact that the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was among those that profited the most in terms of territorial enlargement in the wake of World War I – believed that Yugoslav interests were, to a large extent, unsatisfied and even jeopardised by the order established by the Treaty of Versailles. When reading articles such as Diplomatija iredentizma (Diplomacy of Irredentism)8 and Iz rupe u rupu (From One Hole to Another),9 it becomes clear that the ORJUNA ideologists were dissatisfied with the political map established under the Treaty of Versailles and the organisation of the League of Nations, which served “to break the bones of small nations in a nice way”.10 The negative stance taken by the ORJUNA regarding the existing borders of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and its eagerness to change them in accordance with its agenda was most evidently expressed in the resolution adopted at the ORJUNA assembly that took place in Split on 1 December 1923. Among other things, this document claims: “Faithful to its ideal of an integral Yugoslavia, the ORJUNA shall make every effort to rectify all those international treaties that have separated us from hundreds of thousands of our blood brethren and which have been brought about as a result of foreign imperialist violence and our own discord”.11 The ORJUNA ideologists presented their expansionist agenda to create a Greater Yugoslavia, which would spread over a vast territory from Varna to Trieste and from Szeged to Thessaloniki, as a struggle to create a unified and all-encompassing ethnic body of South Slavs. Such attitude was explicitly articulated in the article Naš put (Our Path),12 which was published on the front page of the first issue of the ORJUNA publication Pobeda (Victory). In this article, an anonymous author made a list of all the tasks that the newly-established state would have to face, highlighting that one of its principal goals was to expand the Yugoslav state to the extent that its borders would eventually be identical to the ethnic ones. Calling upon the right to incorporate all territories belonging to Yugoslav ethnic groups, the ideologists of ORJUNA demanded the inclusion of Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, Rijeka (Fiume), Zadar, Carinthia, Baranja, Aegean Macedonia, and Bulgaria into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which would consequently be renamed as Great Yugoslavia. The ORJUNA ideologists claimed that a unified Yugoslav nation was the main protagonist in the struggle against the anachronistic social and economic forces, religious fanaticism, ignorance, and backwardness. 13 Based on the theory first espoused by Prvislav Grisogono in his pamphlet titled Savremena nacionalna pitanja (Questions of Modern Nationalism) that Slavic tribes used to live in an autochthonous form of democracy,14 the ORJUNA ideologists described the fall of the Slavic tribes under the feudal yoke of the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires as a stage of regression in the political, cultural, and economic development of the Yugoslav nation. The Yugoslav revolution, which had led to the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman Empires during the Balkan Wars and World War I, was perceived as a victory of the progressive Yugoslav forces that fought against the reactionary and backward political, cultural, and economic phenomena (absolutism, clericalism, and feudalism). The primary political objective of the ORJUNA leadership was to incorporate the parts of the Yugoslav nation located outside the territory of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes into their mother country, whereby the capacities of the Yugoslav nation to carry out its cultural and historical mission would be enhanced. 15 In the article titled Jugoslovenska misija (Yugoslav Mission), an anonymous author pointed out that all great nations had a mission to accomplish so as to partake in the humanity, and that the mission of the Yugoslav nation as such was primarily to complete the process of its unification by means of war and to create a greater Yugoslav state, trumpeting that “our Liberation has stemmed from blood. The liberation of our misfortunate brethren who still languish in servitude … will not come to pass in any other way. Their liberation must also stem from our blood…” 16 The ORJUNA ideologists believed that once the ethnic borders of its territory were attained, the historical mission of the Yugoslav nation would be to lead the struggle for the unification of all Slavic nations.17 They argued that the Slavic peoples were a young race with much unused cultural potential that was destined to contribute to the renewal of the decadent Europe.18 The notion held by the ORJUNA ideologists – that by realising its historical mission through the unification of all Slavs, the Yugoslav nation would effectively deliver the decadent European civilisation – actually revealed a messiah complex of its architects, whom it also provided with a rational explanation of the expansionistic actions taken by their followers. In other words, the ideologists of the ORJUNA found a rational explanation for their aggressive course of actions in the field of foreign policy by depicting their expansionist plans as an (altruistically motivated) struggle for the cultural and political improvement of the European community of nations. Their expansionistic agenda was most explicitly set forth in articles such as Govor Predsednika Direktorijuma brata Leontića (Speech Delivered by the President of the Directorate, Brother Leontić),19 Makedonstvujuščima,20 and Bugarska i Jugoslavija (Bulgaria and Yugoslavia).21 The newspapers of the ORJUNA published articles that openly advocated the annexation of territories belonging to the neighbouring countries, i.e. Italy, Austria, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, and Albania. A characteristic example of this can be seen in the congratulations sent by the ORJUNA paper Vidovdan to the royal family on the occasion of the birth of the crown prince, which ends with the exclamation: “Long live the future Yugoslav Emperor, the only ruler of Istria, Gorizia, and the Adriatic”.22 A map published on the front page of the newspaper Yugoslavia, the bulletin of the Belgrade-based ORJUNA committee, provides the most obvious example of the full scope of the territorial pretensions that the ORJUNA had in the neighbouring countries. On this map, Great Yugoslavia is presented as also including the regions of Skadar and Debar, Malesia, Dobruja, the Thracian coast, and Eastern Thrace, in addition to the territories already mentioned. 23

1Jugoslavija (Belgrade), I, No. 14, the National Library of Serbia

3The ORJUNA saw Italy as the main obstacle to the full-blown integration of all territories belonging to the body of the Yugoslav ethnic groups. Mussolini – who presented himself as the leader of the interventionist block that supported Gabriele D’Annunzio in Rijeka and gathered war veterans with the catchphrase “mutilated victory” – placed foreign policy in the very centre of the fascist ideology. The main obstacle to the Italian foray into the Balkans was the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which was the centre of the pro-French alliance Little Entente and stood as a guarantor of the order established under the Treaty of Versailles in Central and Southeast Europe. Aiming to destabilise the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, the fascist regime applied a series of politically subversive measures and terrorist methods which, nevertheless, had poor results. Even before the March on Rome, the Kingdom of Italy endeavoured in every way to obstruct the process of the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The Italian pre-fascist governments occupied Dalmatia; encouraged the formation of the Albanian separatist organisation Kosovo Committee; provided arms and training to the Albanian kachaks 24 and financed their political wing, i.e. the Jemiet political party; incited the so-called Christmas Rebellion, a separatist uprising in Montenegro that took place on 6 January 1919; provided financial support for the organisation of the Montenegrin Army in exile; 25supported the Austrian Heimwehr in the undeclared war between Yugoslavia and Austria over Carinthia; and provided a tacit support to D’Annunzio’s adventurous campaign in Rijeka. This multinational coalition of anti-Yugoslav forces created by Italy before the end of World War I continued to receive support from the new fascist regime, and therefore it continued to carry out its activities throughout the interwar period. 26 In the wake of World War I, the fascist regime established close ties with the Austrian Heimwehr, Gyula Gömbös’ Party of Racial Defense in Hungary, and the circles at the Bulgarian Court. 27 In that way, it besieged the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which became surrounded by revisionist states whose anti-Yugoslav actions were coordinated by the fascist government in Rome. The ORJUNA’s publications paid much attention to all aspects of the anti-Yugoslav actions taken by the Italian fascist government. In articles such as Dve metode (Two Methods),28 Sacro egoism,29 and Italija i naše duhovno jedinstvo (Italy and Our Spiritual Unity),30 the ORJUNA ideologists expressed their view of the Italian foreign policy as, essentially, a continuation of the imperialist legacy of the deceased Habsburg Monarchy, stressing that the same methods would be applied to settle accounts with Italy as was the case with the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In articles such as Musolinijevi ljudi u Trstu pale jugoslovenske domove (Mussolini’s Henchmen Setting Yugoslav Homes on Fire in Trieste),31 Iz zemlje naše tuge (From Our Country of Grief)32 Nova fašistička divljaštva u Goričkoj (New Fascist Barbarism in Gorizia),33 Crnim košuljama (To the Blackshirts)34 i Fašističko pokrštavanje (Fascist Evangelisation),35 the authors called public attention to the brutal terror and assimilation36 that the Yugoslav minority suffered under the fascist regime.37 In the period from 1920 to 1922 only, the members of the fascist militia smashed and demolished the premises of more than 150 centres of cultural, educational, and economic organisations belonging to the Yugoslav ethnic minority in Italy. The most flagrant of these actions was the burning of the Trieste National Hall (13 July 1920) and the Trieste Workers Cultural Centre (10 February 1921) as well as the trashing and destruction of the premises of the editorial staff and printing stores of newspapers Delo (10 February 1921)38 and Edinost (13 July 1920).39 Following the seizure of power by the fascist regime, the entire state apparatus was employed to put even more pressure on the Yugoslav population. Discriminatory laws were enforced that gradually pushed Slovenian language out of education and public use until the regime finally managed to ban and dismantle all cultural, educational, and economic organisations of the Yugoslav minority in 1928.40 Every day, the ORJUNA papers would publish news about the activities of the Italian government and the fascist party in Trieste, Istria, Gorizia, and Dalmatia.

4In articles such as Talijanski fašisti hoće da osnuju borbenu organizaciju u Splitu (Italian Fascists Want to Form a Military Organisation in Split)41 and Lega Nazionale u Šibeniku (Lega Nazionale in Šibenik),42 the authors warned the general public about the subversive activities that the Fascist Party carried out among the members of the Italian ethnic minority in Dalmatia, calling upon the public authorities to take appropriate measures. The ORJUNA papers would also publish news about the many border incidents and incursions of the fascist militia into the territory of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The ORJUNA papers stressed that its members were the only well-organised force that resisted such incursions and thus made great sacrifices for the Homeland.43 In articles such as Hrvatski borac (Croatian Fighter),44 Poslednji Mohikanci (The Last Mohicans)45 and Musolini izmišlja tako zvano Crnogorsko pitanje (Mussolini Invents the so-called the Montenegro Question),46 the authors accused the fascist government of supporting the separatist movements in Croatia and Montenegro. Articles such as Albansko pitanje (The Albanian Question),47 Pred Musolinijev podvig na Balkanu (Ahead of Mussolini’s Feat in the Balkans)48 i Natezanje sa Musolinijem (Bickering with Mussolini)49 make it clear that the ORJUNA papers paid close attention to the steps taken by the Italian government in Albania. The authors agreed in their opinions that the Tirana Pact served to strengthen the Italian influence in the Eastern Adriatic and that it posed a threat to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The ORJUNA ideologists believed that Italy would use its newly-established influence in Albania to incite a rebellion of kachaks in the territory of Old Serbia (Kosovo and Metohija as well as Macedonia), which would provide them with an excuse to attack the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Many articles published in the ORJUNA papers – such as Sloboda Jadranskog mora (Freedom of the Adriatic Sea)50 and Italija na Sredozemnom moru (Italy in the Mediterranean Sea)51 – cautioned that Italy would sooner or later attack the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes with the aim of seizing the territories that had been promised to it under the Treaty of London. In articles such as Musolinijeva agresivnost i naša spoljna politika (Mussolini’s Aggressiveness and Our Foreign Policy),52 authors warned the public that the aggressive plotting of the fascist Italy was backed by Great Britain, while France remained indifferent to the Yugoslav-Italian conflict. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was therefore mostly left to its own devices. Notwithstanding such grim prospects, the ORJUNA members had no doubts about the outcome of an armed conflict between Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Their firm belief that they would be victorious in such a war was most explicitly expressed in the article Naš prekomorski sused i mi (Our Overseas Neighbor and Ourselves),53 whose anonymous author states that in case of war, the mighty Italian fleet would surely seize the Yugoslav islands and destroy the coastal towns, but that the army of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes would advance into the River Po valley and conquer large Italian cities, thus annulling the conquest made by the Italian naval forces. In its campaign aimed against the aggressive policies of the fascist Italy, the ORJUNA (itself strongly anti-communist) even employed a tactic of cooperating with the left-wing opposition to Mussolini’s regime.54 A testimony to this can be found in the article Protiv rata sa Jugoslavijom (Against the War with Yugoslavia),55 a declaration made by the antifascist left-wing organisation Head Committee for Workers’ Defence against Fascism, published on the front page of the ORJUNA paper Vidovdan. Reacting to the provocations of Italian fascists in the border zone, the ORJUNA action squads made various forays into the Italian territory, attacking Italian military garrisons and fascist militia posts.56 In the early 1920s, the ORJUNA action squads came into conflicts with the Italian Army and fascist militia, mostly as a defensive reaction. Of these defensive actions, it is worth mentioning two events taking place in October 1922 and August 1923 respectively, when the ORJUNA drove out a fascist militia squad that tried to occupy Sušak and when the ORJUNA members clashed with the Italian Army on Mount Triglav. 57

5Reacting to such outright provocations of the fascist Italy and the aggressive stance assumed by its satellites, in the mid-1920s, the ORJUNA formed its secret organisations in the territories of Italy and Austria. The key role in their establishment was played by the members of its Slovenian branch (the local committees in Ljubljana and Maribor), namely Marko Kranjec, Andrej Verbič, Anton Kukec, and Ivan Rehar. The most notable ORJUNA border-zone organisation was ORJUNAVIT (abbreviation for the Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists in Italy), founded in 1925 in the Julian March. When ORJUNAVIT was established, the ORJUNA members used the existing organisation called the TIGR (abbreviation for Trieste-Istria-Gorizia-Rijeka), which had been founded in 1924 in Trieste, 58 and brought together the members of the Slovenian and Croatian ethnic minorities living in the Italian territory.59 Initially, this organisation, led by the lawyer Ivan Marija Čok,60 was engaged primarily in cultural and educational activities aimed at the Slovenian and Croatian population in the Italian territory.61 It did not have a clearly defined ideology. Instead, it was a heterogeneous group of political and cultural cliques that had a wide range of political views. 62 According to the account given by Dorče Sardoč (one of the activists of the TIGR organisation), the youth that gathered within the TIGR and, later on, the ORJUNAVIT came from various political groups (ranging from communists to Christian socialists and liberals). All of these groups emphasised that their political differences were of secondary importance and that they all subscribed to the ideal that they shared: to make Venezia Giulia a part of the Yugoslav territory. 63 This assertion was further confirmed by the fact that one of the arrested activists claimed to the Italian authorities that he was a member of the Italian Communist Party and the ORJUNA.64 Led by Marko Kranjec, the TIGR joined about 20 other cultural and educational organisations of the Yugoslav ethnic minority, which united in the ORJUNAVIT (abbreviation for the Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists in Italy) in December 1925. 65 The management board of this newly-established organisation was formed by Kranjec and Verbič from the ORJUNA and by Gaberšek, Rejec and Kocijančić as the representatives of the Yugoslav ethnic minority organisations in Italy.66

6The ORJUNAVIT leadership divided the Julian March territory into six operative zones and established an armed squad and an intelligence network, managed by a commander, in each of them. 67 According to the information of the Italian government, an important role in the organisation of ORJUNAVIT activities in Italy was played by its Great Chief, the Chetnik military commander Ilija Trifunović Birčanin, who marshalled the Yugoslav irredentist actions in the Julian March based on his experience with the Chetnik actions carried out in Macedonia between 1903 and 1912. 68 Consequently, the ORJUNA members in Italy organised themselves in troikas that kept their activities top secret. 69 Recruited from the Yugoslav ethnic minority in Italy, Yugoslav refugees from the Julian March, and Italian antifascists, the ORJUNAVIT members spread antifascist propaganda, gathered intelligence and information of military and political importance, and sabotaged military posts and transport infrastructure.70 According to the information of the Italian Ministry of Internal Affairs in the 1926–1930 period, the ORJUNAVIT carried out 99 acts of sabotage and terrorism. 71 Certain documents indicate that when carrying out such tasks, the ORJUNAVIT cooperated with Andreas-Hofer-Bund, an illegal German ethnic minority organisation affiliated with the Austrian fascist organisation Heimwehr, which was active in South Tyrol. 72 This fact is seemingly paradoxical, given that the ORJUNA was openly antagonistic to Heimwehr with regard to the question of the Austrian province of Carinthia. The biggest armed actions carried out by the ORJUNAVIT included the assault on the printing shop of a local fascist paper in Trieste and the assault on the Italian military garrison in Postojna. 73 The first action, carried out by the Action Squad in the Italian territory, was the assault in Prestranek. On 3 April 1926, a group of five armed ORJUNA members crossed the border, broke into the ticket office at the Prestranek railway station, threatened the Italian clerks with firearms, and walked off with a sum of 246,000 lire. On the way back, before they entered the Yugoslav territory, they were intercepted by a fascist militia troop. A shootout ensued in which two ORJUNA members and two fascist militia members lost their lives. The money stolen by the ORJUNA members was intended for the acquisition of firearms for the ORJUNAVIT fighters operating in Italy. 74 Another significant armed action, carried out by the ORJUNAVIT in Italy, was the assault on the National Home in Trieste, which was the seat of the local branch of the Fascist Party and the editorial office of the local fascist paper. On 8 March 1926, a small group of ORJUNAVIT activists (Jakob Geržem i Herman Šolar)75 machine-gunned the façade of the building and threw a bomb at the editorial office premises.76 On 3 November 1926, the ORJUNA members planted an explosive device in the army barracks of the fascist militia in Saint Peter in Krain, killing three fascist militiamen. In the first half of 1927, the ORJUNA members performed several armed attacks on the fascist militia border patrols, killing several more fascist militiamen. 77 In addition to terrorist actions, the ORJUNAVIT also engaged in various military intelligence activities. When the ORJUNAVIT was founded in 1926, the ORJUNA’s Great Chief Marko Kranjec established contacts with the intelligence unit of the Drava Division Corps and the Ministry of Defence, which provided financial resources to set up the ORJUNAVIT intelligence network in Italy. 78 The ORJUNAVIT and the Yugoslav Army had close connections, as attested to by the fact that the intelligence unit of this organisation that covered the area stretching from Postojna to Vipava was headed by Stanko Lavrenčić – an active-duty officer of the Yugoslav Army (as well as an emigrant from Postojna). 79 A part of the intelligence obtained by the ORJUNAVIT was also forwarded to the French Consulate,80 which, in return, partially funded the ORJUNA secret service in Italy.81 The ORJUNA agents obtained some of the information by bribing Italian Army officers and fascist militia, while funds for that purpose were provided through the Yugoslav Consulate in Trieste.82 Many servicemen belonging to the Yugoslav ethnic minority were among the ranks of the Italian Army and fascist militia, which made it easier for the ORJUNAVIT to infiltrate these formations with the aim of setting up its intelligence network within their ranks. With the help of such collaborators, the ORJUNAVIT activists would, on many occasions, carry out their subversive intelligence and sabotage activities dressed in the uniforms of the fascist militia and the Italian Army. 83 The ORJUNA intelligence service was not active only in the Italian territory, as its agents managed to gain long-term insight into the official correspondence of the Italian Consulate in Ljubljana. 84 At that point, the ORJUNA members uncovered information indicating that a number of agents working for the Italian secret service had infiltrated their ranks. This information led to a conflict within the ORJUNA organisation itself. On Marko Kranjec’s orders, the ORJUNA members killed Eduard Perić, a member of the organisation whose name was discovered on the list of the Italian secret agents at the Italian Consulate in Ljubljana. Following this assassination, Kranjec was arrested, together with his closest collaborators Andrej Verbič and Anton Kukec. 85

7The irredentist ORJUNA actions gained new momentum with the events that took place on 18 June 1926. On that day, an ORJUNA unit in Ljubljana organised a gathering of its members on the occasion of a flag consecration ceremony, after which the members formed a procession that was supposed to march through Ljubljana. Some 800 ORJUNA members headed toward the centre of the city. There they came across police cordons that stopped them on their way to the building of the Italian Consulate in the Prešernova ulica street to prevent any possibility of anti-Italian protests. After a brief argument with Leontić and Kranjec, who were leading the crowd, the police commissioners directed the ORJUNA procession into the streets that go around the Italian Consulate. A group of approximately 150 ORJUNA members became infuriated with the police reaction, so they attacked the police cordon, trying to push through it and get to the Italian Consulate. Following a ten-minute brawl, in which the police used rubber truncheons and sabres, several ORJUNA members opened fire at the police, which responded in kind. After the shooting, in which more than 70 bullets were fired, the ORJUNA members ran off. Three people were seriously wounded in the skirmish, while another six policemen and three ORJUNA members suffered minor injuries. Following this incident, 68 ORJUNA members were arrested and another 18 were taken into custody and charged with attacking police officers. The ORJUNA leaders accused the police forces that they opened fire first, claiming that the ORJUNA members merely reacted in self-defence. The trial against the perpetrators of this incident did not result in any verdicts due to the lack of evidence (as they fled, the ORJUNA members threw their guns in the river Ljubljanica). 86 Pressing charges against the ORJUNA unit in Ljubljana for endangering the public safety and order, the Government officially banned it on 29 June 1926. However, the members of the Slovenian ORJUNA continued to take actions regardless of the government prohibition, using their bulletins to ridicule the state authorities. Following this incident, the members of the Slovenian ORJUNA, led by Kranjec, reorganised themselves and continued resolutely to carry out their underground irredentist activities in Italy. In the first half of 1927, the ORJUNA organised its units in Trieste and initiated a series of field actions, of which the establishment of the clandestine paper Borba should be pointed out.87 In May 1927, the military authorities in Sušak warned police officers that the local ORJUNA members were planning to take advantage of Mussolini’s visit to Trieste on 24 May to assassinate him. As a result of that timely information, the police managed to arrest the ringleaders behind this plan, thus preventing a severe diplomatic incident. 88 In November 1927, the Drava Division Corps command informed the General Staff that the ORJUNA action squads had made an incursion into the Italian territory and opened fire on the Italian Army, the police, and the fascist militia. The command pointed out that the ORJUNA members stated they carried out those actions following the orders of the military and underlined the dangers of spreading such false news. 89 During 1928, the best members of the ORJUNA action squads from Slovenia were assembled to form a special combat unit called Crni Vrazi (Black Devils), which was supposed to carry out terrorist actions in Italy.90 In 1928, the ORJUNA squads, reorganised in that manner, carried out a series of attacks on the fascist militia border patrols. The most dramatic of these were the assault on 20 February (when three fascist militiamen were wounded) and the one launched on 1 July (when two squad members were killed). In both of these instances, the ORJUNA members went into hiding in the territory of the Kingdom SHS after launching the attacks. The last of these incidents provoked a reaction from the Italian authorities, which arrested a large number of people suspected to be members of the ORJUNA border-zone organisation. 91 In June 1928, the Italian Ministry of the Internal Affairs warned the Italian authorities in Dalmatia that a number of ORJUNA groups, whose task was to set Italian schools on fire, had infiltrated the region and ordered that the fascist militia should secure the school buildings in Zadar.92 The intensified ORJUNA terrorist actions in Italy eventually led to a conflict within the organisation. After the ORJUNA squads had assaulted Prestranek in 1926, the TIGR left the ORJUNAVIT, believing that Marko Kranjec was much too hot-tempered and prone to reckless actions. 93 There are certain indications suggesting that the cooperation between these two organisations in fact ended due to a conflict over the division of loot taken in the assault on the railway station in Perestranka. Namely, the leaders of the TIGR accused Marko Kranjec of using all of the plunder for the ORJUNA’s needs in the Kingdom of SHS, while Kranjec claimed that the looted money intended for the requirements of the organisation in Italy was kept by Raiko Samso, who was among the raiders that launched the assault in Perestranka. This question remained unresolved, and it was believed that Samso’s murder in June 1929 was an act of revenge by Kranjec. 94

8Some of the ORJUNA members from Slovenia, led by Vladimir Levstik, believed that armed actions in Italy were counterproductive and that they would result in the dissolution of the movement. When Kranjec and his closest collaborators were arrested in December 1928 for the murder of Eduard Perić, Levstik was appointed by the ORJUNA Secretary-General Miodrag Dimitrijević to take over the administration of the organisation in Slovenia and tasked with putting an end to the practice of plotting terrorist actions in Italy. 95 The terrorist actions carried out by the ORJUNA and its affiliated organisation across the border in Italy played an important part in the dissolution of the organisation following the promulgation of the January 6th Decree. In the words of Vladimir Levstik, one of the leaders of the Slovenian ORJUNA, the terrorist actions plotted by Marko Kranjec in the territories of Italy and Austria were the main reason why the regime made ORJUNA illegal in the wake of the January 6th Decree.96 Once he was released from prison, Kranjec refused to abide by the state decree that banned ORJUNA and its affiliated organisations across the border and continued to plot terrorist actions in Italy, 97 which is telling enough and counters the assumption that the ORJUNA was under the direct control of the Belgrade-based government and its military command. Marko Kranjec was known to the Italian intelligence service, which suspected that the ORJUNA continued its activities within the National Defence. The information available to the Italian secret agents indicated that Kranjec enjoyed the support of the Chetnik military commander Kosta Milovanović Pećanac, an experienced guerrilla fighter who had plotted the incursions of the ORJUNA squads into the Italian territory. 98 In January 1929, Italian secret agents warned the Italian border authorities that the ORJUNA had issued a circular letter to its members announcing that a war between Italy and France was imminent, and that the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes would take part in it as France’s ally, while the role the ORJUNA had to play in that conflict was to incite riots in Dalmatia and Albania.99 The Italian secret service particularly emphasised the fact that the ORJUNA (which at that time operated under the cloak of the National Defence) possessed 70,000 firearms that would be used against Italy in the coming spring. 100 In February 1929, Kranjec formed an unarmed squad in Sušak, which was supposed to make a foray into the Italian territory.101 The Italian border authorities stressed that the members of the dissolved ORJUNA intensified their activities in March and April 1929. The Italian secret agents pointed out that the ORJUNA members from Ljubljana disseminated antifascist (communist) literature and leaflets in Italy. 102 In March 1929, the Italian intelligence service reported that the ORJUNA members organised special groups intending to carry out a series of assassinations of high-ranked Fascist Party officials.103 In early 1930, the ORJUNA members from Slovenia, led by Marko Kranjec, established ties with the Italian antifascist emigrants in Paris, who would join the fight against the fascist regime in Italy. These political émigrés were mostly members of the Italian Communist Party, and the Yugoslav authorities therefore feared that the former ORJUNA members would fall under the influence of Communist propaganda. These fears motivated the Yugoslav authorities to move Kranjec, considered to be the mastermind behind the irredentist actions, from the customs offices in Slovenia first to Skopje 104 and then to Niš.105 On Saturday, 2 September 1930, the ORJUNA organisation across the border in Italy suffered a severe blow when Jože Kukec, one of the most prominent activists in the movement, was killed in a skirmish with the fascist militia.106 The situation was additionally complicated by the fact that the Italian authorities found a number of compromising documents in Kukec’s possession, which endangered the very existence of the ORJUNA’s activist and intelligence network in Italy.107 In October 1930, when Kranjec left Slovenia, the ORJUNA squads that carried out terrorist actions in Italy reorganised themselves within the Propaganda Department on the Coast. The head commander of these squads was General Rudolf Maister, who had played a prominent role in the war that Yugoslavia had waged against Austria in 1918–1919 over Styria and Carinthia, and who would later become the honorary president of the Association of Fighters of Yugoslavia BOJ. Under his command, these squads stopped plotting terrorist actions in Italy and instead focused their activities on patrolling the border and taking in the fugitives from Italy. 108 Later on, most of the ORJUNA members from this organisation continued their activities in the Drava Banate within the National Defence, 109 which was led by Josip Cepuder, a former leader of the ORJUNA branch in Ljubljana.110

9The ideologists of the ORJUNA were particularly mistrustful of Austria as the successor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that kept pursuing the Habsburg pretensions in the Balkan Peninsula. This was most explicitly expressed in the article Balkanske stvari (Balkan Issues),111 whose anonymous author pinpointed Vienna as the epicentre of various anti-Yugoslav groups that freely gathered and operated there, ranging from the Croatian pro-Habsburg loyalists, organised under the command of Lieutenant Field Marshal Stjepan Sarkotić, to groups of clericalists and Hungarian nationalists, to Soviets who used their embassy to support the Communist Party in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. However, in the ORJUNA’s opinion, the Austrian province of Carinthia was the main point of dispute between the two neighbouring countries. This territorial dispute dated back to the final stage of World War I, when Slovenian nationalists, encouraged by the presence of the Serbian Army, undertook a large-scale action aiming to incorporate this province into the newly-formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. As a reaction to these challenges, units of volunteers were formed throughout Austria under the name of Heimwehr (Home Guard), intended to counter the incursions from the neighbouring countries. In this conflict, the Heimwehr forces (politically and financially supported by Italy and right-wing groups from Germany) were defeated, while the Slovenian volunteer units secured the cities of Maribor and Celovec (Klagenfurt). 112 The Triple Entente decided that the dispute over these territories would be settled by means of a plebiscite in 1920. At that point, most of Carinthia remained a part of Austria, whereas Styria and the city of Maribor were included into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. 113 This undeclared war between the hostile volunteer units resulted in the ideological radicalisation on both sides of the newly-established border. In Austria, groups within the Heimwehr, which had previously not carried out joint operations, started to become aware that they had to cooperate with one another. The idea of Pan-Germanism was on the rise, whereas in the Slovenian regions within the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes the ideology of Yugoslav integralism was taking root together with the idea of Great Yugoslavia – a country that would eventually regain Carinthia and Styria, populated by Slovenians, from Austria. Many Slovenian members of the ORJUNA took part in this undeclared war, and the issue of Carinthia and its incorporation into Yugoslavia was argued for in many articles published in the ORJUNA newspapers, such as Diplomacija iredentizma (Diplomacy of Irredentism),114 Beč i Beograd (Vienna and Belgrade),115 Govor Predsednika Direktorijuma brata Leontića (Speech Delivered by the President of the Directorate, Brother Leontić),116 Koruška (Carinthia),117 and Orjunaši u Koruškoj (ORJUNA in Carinthia).118 The ORJUNA ideologists did not accept the results of the Carinthian plebiscite, believing that it was symptomatic of the repression that Slovenians in Carinthia were subjected to by the Heimwehr and the representatives of the Austrian authorities. 119 Consequently, the ORJUNA did not give up or abandon its claim that this territory should become a part of the Yugoslav state120 as soon as the international relations made such an outcome achievable.121 Just like in the case of Istria, Trieste, and Gorizia, the ORJUNA took concrete steps with the aim of facilitating the incorporation of Carinthia into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In the 1920s, the ORJUNA established its illegal organisation in the territory of Carinthia called Fantovska zveza. Set up similarly as the ORJUNAVIT, the Fantovska zveza organisation carried out armed attacks in Carinthia, assaulting the representatives of the Austrian government and local Austrian nationalists. The most prominent action carried out by the Fantovska zveza was the assault in Celovec (Klagenfurt) in December 1925, on the occasion of the 6 th anniversary of the Carinthian plebiscite. The police informers who had infiltrated the ORJUNA tipped off the gendarmerie corps in Ljubljana, informing them that the ORJUNA, in cooperation with the Action Squads from Maribor, was plotting to launch an attack on the Austrian border somewhere around Pliberk (Bleiburg), while the fighters from the Fantovska zveza, assisted by the Action Squads, would make a simultaneous attack on the attendees of the celebration in Celovec. The members of the Action Squads and the Fantovska zveza were armed with guns and bombs, and the latter had already planted infernal machines (time bombs) in the city centre of Celovec, where they would be detonated prior to the assault. The assault was supposed to be a reprisal for the persecution of the Slovenian population in Carinthia, for which the Heimwehr was responsible. Having received a timely warning, the gendarmerie corps in Ljubljana arrested the ringleaders behind this action, although some ORJUNA members managed to get away and cross over to the Austrian territory, where they were captured by the Austrian police. 122

10Overall, the irredentist actions of the Slovenian ORJUNA in Italy and Austria did not have a significant influence on the foreign-political situation of that time. Their intensity and violent character faithfully reflected the legacy of the ethnic conflicts in the Habsburg Monarchy at the end of the 19th century as well as the reception of the modern political practice of the ideological system that came to power in Italy in 1922. Guided by the imperative of preserving the ethnic identity of the Slovenian population in the marginal provinces of Italy and Austria, the ORJUNА leadership promoted the systematic use of organised violence as a basic tool in the struggle to achieve its goals. Due to the restrained and legitimately oriented official foreign policy of the Yugoslav governments as well as because of the armed resistance provided by the official security forces and paramilitaries of Italy and Austria, the leadership of the ORJUNA failed to achieve its foreign-political goals through the use of terror. On the other hand, the expansionist ideas that represented one of the essential tenets of the ORJUNA’s ideology would remain a part of the ideological concepts espoused by all far-right movements that supported the Yugoslav integralism in the interwar period, which, with slight modifications, adopted the ideological constructs advocated by the Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists. In their political agendas and manifestos, the Yugoslav Action, Association of Fighters of Yugoslavia, and the Yugoslav National Movement Zbor would embrace and cherish the idea of the Greater Yugoslavia, whose borders would be more or less identical to the model established by the ORJUNA ideologists. The rise of revanchist states, restrictive security policies applied by the Yugoslav regimes, and rudimentary organisational forms of paramilitary militias in the 1930s were the factors that frustrated the leaderships of the far-right movements for Yugoslav integralism in their attempts to employ direct violent irredentist actions to further their expansionist agenda, thus restricting their activities to the field of culture and education, propaganda, and cooperation with the pro-Yugoslav elements in the neighbouring countries.

Sources and Literature

- AY – Archives of Yugoslavia:

- ○ Ministarstvo pravde Kraljevine Jugoslavije (Fund No. 63).

- CSA – Croatian State Archives:

- ○Režimske i reakcionarne organizacije - grupa VII.

- SI AS – The Archives of the Republic of Slovenia:

- ○ SI AS 1931, Republiški secretariat za notranje zadeve SRS.

- Bartulović, Niko. Od revolucionarne omladine do ORJUNE: Istorijat jugoslovenskog omladinskog pokreta. Split: ORJUNA, 1925.

- Bosworth, J.R.B. Mussolini’s Italy: Life under the Dictatorship 19151945. London: Penguin Books, 2006.

- Čop, Robert. "ORJUNA prototip političke organizacije." Graduation thesis defended at the Faculty of Social Sciences in Ljubljana, 2006.

- Djordjević, Mladen. “Organizacija jugoslovenskih nacionalista (ORJUNA).” NSPM, Vol. XII, No. 1-4 (2006).

- Ekmečić, Milorad. Stvaranje Jugoslavije 1790-1918 II. Belgrade: Prosveta, 1989.

- Ferenc, Tone, Kacin-Wohinz, Milica in Tone Zorn. Slovenci v zamejstvu: Pregled zgodovine 1918-1945. Ljubljana: Državna založba Slovenije, 1974.

- Filipič, France. „Nekaterne značilnosti delavskega revolucionarnega gibanja v Mariboru in njegovem zaleđu v letih 1921–1925.“ Revolucionarno delavsko gibanje v Sloveniji v letih 1921-1924: Referati z znanstvenega posvetovanja v Ljubljani 6. in 7. junija 1974, 151-173. Ljubljana, 1975.

- Gligorijević, Branislav. „Organizacija jugoslovenskih nacionalista (Orjuna).“ Istorija XX veka: zbornik radova (1962).

- Gligorijević, Branislav. „Politički pokreti i grupe sa nacionalsocijalističkom ideologijom i njihova fuzija u Ljotićevom Zboru.“ Istorijski glasnik, No. 4 (1965).

- Gligorijević, Branislav. Kralj Aleksandar Karadjordjević: Srpsko-hrvatski spor. Belgrade: Zavod za udzbenike i nastavna sredstva, 2002.

- Grisogono, Prvislav. Savremena nacionalna pitanja. Split: ORJUNA, 1923.

- Kacin-Wohinz, Milica. Narodnoobrambno gibanje primorskih Slovencev v letih 1921-1928 II. Koper: Lipa; Trst: Založništvo tržaškega tiska, 1977.

- Kacin-Wohinz, Milica. „Slovenci i Hrvati pod fašističkom Italijom.“Jugoslovenski istorijski časopis, No. 3 (1987).

- Kacin-Wohinz, Milica. Prvi antifašizem v Evropi. Koper: Lipa, 1990.

- Mlakar, Boris. „Radical Nationalism and Fascist Elements in Political Movements in Slovenia Between the Two World Wars.“ Slovene studies, No. 1 (2009).

- Mlakar, Boris. „Zaton Organizacije jugoslovanskih nacionalistov - Orjune pod budnim očesom italjanskih fašističnih oblasti.“ Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino, No. 2

- Payne, Stanley G. A History of Fascism 1914-1945. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003.

- Perovšek, Jurij. V zaželjeni deželi: slovenska izkušnja s Kraljevino SHS/Jugoslavijo 1918-1941. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2009.

- Vodušek Starič, Jerca. Slovenski špijoni in SOE 1936-1942. Ljubljana: samozal., 2002.

- Budućnost, I, No. 3, 30th December 1922. “Hrvatski borac.”

- Budućnost, I, No. 3, 30th December 1922. “Poslednji Mohikanci.”

- Budućnost, II, No. 9, 3rd March 1923. “Beč i Beograd.”

- Jugoslavija (Belgrade), II, No. 26, date illegible (year 1928). “Fašističko pokrštavanje.”

- Jugoslavija (Belgrade), II, No. 26, date illegible (year 1928). “Sacro egoism.”

- Jugoslavija (Skopje), I, No. 2, 20th February 1927. “Crnim košuljama.”

- Jugoslavija (Skopje), I, No. 3, 28th February 1927. “Makedonstvujuščima.”

- Jugoslavija (Skopje), I, No. 5, 27th March 1927. “Bugarska i Jugoslavija.”

- Lahman, Ivo. “Kulturno Jugoslovenstvo.” Pobeda, I, No. 7, 24th September 1921.

- Leontić, Ljubo. “Govor Predsednika Direktorijuma brata Leontića.” Pobeda, V, No. 40, date illegible (year 1925).

- Leontić, Ljubo. “Sloboda Jadranskog mora.” Jugoslovenski Jadran – special ORJUNA publication published on the occasion of its meeting in Dubrovnik, 23rd – 24th March 1926.

- Orjuna, I, No. 30, 15th July 1923. “Iz zemlje naše tuge.”

- Orjuna, I, No. 30, 15th July 1923. “Obnavljanje nemčurstva v severni Sloveniji.”

- Orjuna, II, No. 51, 18th October 1924. “Spominski shod za Koroško u Mariboru.”

- Pobeda, I, No. 1, 28th June 1921. “Naš put.”

- Pobeda, I, No. 6, 17th September 1921. “Dve metode.”

- Pobeda, No. 7, 24th September 1921. “Diplomatija iredentizma.”

- Pobeda, I, No. 19, 24th December 1921. “Jugoslovenska misija.”

- Pobeda, V, No. 31, date illegible (year 1925). “Naš prekomorski sused i mi.”

- Pobeda, V, No. 66, date illegible (year 1925). “Koruška.”

- Pobeda, V, No. 69, date illegible (year 1925). “Talijanski fašisti hoće da osnuju borbenu organizaciju u Splitu.”

- Pobeda, V, No. 72, date illegible (year 1925). “Musolinijevi ljudi u Trstu pale jugoslovenske domove.”

- Pobeda, V, No. 78, date illegible (year 1925). “Orjunaši u Koruškoj.”

- Pobeda, VI, No. 18, date illegible (year 1926). “Svesni orijunaši na granici u službi Otadžbine.”

- Pobeda, VI, No. 66, date illegible (year 1926). “Nova fašistička divljaštva u Goričkoj.”

- Pobeda, VII, No. 3, 22nd December 1927. “Musolini izmišlja tako zvano Crnogorsko pitanje.”

- Pobeda, VII, No. 4, 29th January 1927. “Lega Nazionale u Šibeniku.”

- Pobeda, VII, No. 9, date illegible (approximately February-March 1927). “Albansko pitanje.”

- Pobeda, VII, No. 10, date illegible (year 1927). “Italija i naše duhovno jedinstvo.”

- Pobeda, VII, No. 10, date illegible (approximately February-March 1927). “Pred Musolinijev podvig na Balkanu.”

- Pobeda, VII, No 28, 15th July 1927. “Musolinijeva agresivnost i naša spoljna politika.”

- Pobeda, VII, No. 29, 29th April 1927. “Natezanje sa Musolinijem.”

- Silobrćić, J. M.. “Naša borba.” Orjuna, II, No. illegible, 25th March 1923.

- Vidovdan, II, No. 90, 6th October 1923. “Protiv rata sa Jugoslavijom.”

- Vidovdan, V, No. 322, 28th February 1926. “Balkanske stvari.“

- Vidovdan, VI, No. 377, 15th January 1927. “Iz rupe u rupu.”

- Vidovdan, VI, No. 397, 22nd May 1927. “Italija na Sredozemnom moru.”

Vasilije Dragosavljević

IREDENTISTIČNE AKCIJE SLOVENSKE ORGANIZACIJE JUGOSLOVANSKIH NACIONALISTOV (ORJUNE) V ITALIJI IN AVSTRIJI (1922–1930)

POVZETEK

1V prispevku so predstavljeni konceptualni okviri zunanjepolitičnih idej Organizacije jugoslovanskih nacionalistov (Orjune). V uvodnem delu članka sta tako opisana kratka zgodovina Orjune in proces razvoja njene ideologije s poudarkom na ekspanzionistični ideji. Ekspanzionistični načrti vodilnih Orjuninih ideologov, utelešeni v načrtu Velike Jugoslavije, ki bi segala od Varne do Trsta in od Szegeda do Soluna, so bili neločljivo povezani s teorijo jugoslovanskega integralizma, v skladu s katero naj bi na tem ozemlju živeli izključno jugoslovanski prebivalci. Orjunini ideologi so bili prepričani, da mora biti enotnost Jugoslovanov najpomembnejša vodilna ideja jugoslovanske zunanje politike. Vodstvo Orjune je na podlagi imperativa ohranitve etnične identitete slovenskega prebivalstva v pokrajinah ob meji z Italijo in Avstrijo zagovarjalo sistematično uporabo organiziranega nasilja kot osnovnega orodja v boju za uresničitev svojih ciljev. Posebna pozornost je posvečena iredentističnim akcijam, ki jih je slovenska veja Orjune opravila na ozemlju Italije (Trst, Gorica in Istra) in Avstrije (Koroška). Izpostavljeni sta tudi organizaciji Orjunavit in Fantovska zveza, ki sta Orjuni služili kot orodje za delovanje na ozemlju Italije in Avstrije. Zmerna in legitimno usmerjena uradna zunanja politika jugoslovanskih oblasti ter oboroženi odpor uradnih varnostnih sil in paravojaških organizacij Italije in Avstrije sta vodstvu Orjune preprečila, da bi s terorizmom doseglo svoje zunanjepolitične cilje. Ekspanzionistične ideje kot ena glavnih značilnosti Orjunine ideologije so se v medvojnem obdobju ohranile v okviru idejnih konceptov vseh skrajnih desničarskih gibanj za jugoslovanski integralizem. Ta so z manjšimi ali večjimi spremembami sprejela ideološke konstrukte, ki jih je zagovarjala Orjuna.

* Dr., Istorijski Institut Beograd, Knez Mihajlova 36/II, SR-11000 Beograd, v.dragosavljevic@yahoo.com

1. Originally, the name of the organisation was the Yugoslav Progressive Nationalist Youth (JNNO). In May 1922, having changed its articles of association, a new name was adopted – i.e. the Organisation of Yugoslav Nationalists – the ORJUNA.

2. Mladen Djordjević, “Organizacija jugoslovenskih nacionalista (ORJUNA),” NSPM, Vol. XII, No. 1–4 (2006): 188–93.

3. Branislav Gligorijević, “Organizacija jugoslovenskih nacionalista (ORJUNA),” Istorija XX veka: Zbornik radova V (Beograd, 1963), 326–31.

4. Ibid., 333–38.

5. Djordjević, “Organizacija jugoslovenskih nacionalista,” 202–07.

6. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvesture o Orjuni (report of 26 January 1929). SI AS 1931, 935-600-12, document: Elaborat o ORJUNI.

7. Branislav Gligorijević, “Politički pokreti i grupe sa nacionalsocijalističkom ideologijom i njihova fuzija u Ljotićevom Zboru,” Istorijski glasnik, No. 4 (1965): 41–43.

8. “Diplomatija iredentizma,” Pobeda, I, No. 7, 24 September 1921.

9. “Iz rupe u rupu,” Vidovdan, VI, No. 377, 15 January 1927.

10. Ibid.

11. Niko Bartulović, Od revolucionarne omladine do ORJUNE: Istorijat jugoslovenskog omladinskog pokreta (Split: ORJUNA, 1925), 113.

12. “Naš put,” Pobeda, I, No. 1, 28 June 1921.

13. Ivo Lahman, “Kulturno Jugoslovenstvo,” Pobeda, I, No. 7, 24 September 1921.

14. Prvislav Grisogono, Savremena nacionalna pitanja (Split: ORJUNA, 1923), 7.

15. “Jugoslovenska misija,” Pobeda, I, No. 19, 24 December 1921.

16. Ibid.

17. The ideologists of the ORJUNA were not clear about the way in which the unification of Slavic countries was to be accomplished. Given that Russia, as the biggest Slavic country, was at the time under the Bolshevik regime, which denied its nationhood, it makes sense to ask how Russia could become involved in such unification process – that is, whether the ORJUNA ideologists had plans to carry out an armed intervention to topple the Bolshevik regime in the USSR.

18. J. M. Silobrćić, “Naša borba,” Orjuna (Ljubljana), 25 March 1923.

19. “Govor Predsednika Direktorijuma brata Leontića,” Pobeda, V, No. 40, date illegible.

20. “Makedonstvujuščima,” Jugoslavija (Skopje), I, No. 43, 28 February 1927.

21. “Bugarska i Jugoslavija,” Jugoslavija (Skopje), I, No. 5, 27 March 1927.

22. Vidovdan, II, No. 82, 8 September 1923, 1.

23. Jugoslavija (Belgrade), I, No. 14, 1 December 1927, 1.

24. J.R.B. Bosworth, Mussolini’s Italy: Life under the Dictatorship 1915–1945 (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 283, 284.

25. Branislav Gligorijević, Kralj Aleksandar Karadjordjević: Srpsko-hrvatski spor (Belgrade: Zavod za udzbenike i nastavna sredstva, 2002), 160–65.

26. Milorad Ekmečić, Stvaranje Jugoslavije 1790-1918 II (Belgrade: Prosveta, 1989), 820–25, 827.

27. Bosworth, Mussolini’s Italy, 284.

28. “Dve metode,” Pobeda, I, No. 6, 17 September 1921.

29. “Sacro egoismo,” Jugoslavija (Belgrade), II, No. 26, date illegible (year 1928).

30. “Italija i naše duhovno jedinstvo,” Pobeda, VII, No. 10, date illegible (year 1927).

31. “Musolinijevi ljudi u Trstu pale jugoslovenske domove,” Pobeda, V, No. 72, date illegible (year 1925).

32. “Iz zemlje naše tuge,” Orjuna, I, No. 30, 15 July 1923.

33. “Nova fašistička divljaštva u Goričkoj,” Pobeda Vi, No. 66, date illegible (year 1926).

34. “Crnim košuljama,” Jugoslavija (Skopje), I, No. 2, 20 February 1927.

35. “Fašističko pokrštavanje,” Jugoslavija (Belgrade), II, No. 26, date illegible (year 1928).

36. Boris Mlakar, “Radical Nationalism and Fascist Elements in Political Movements in Slovenia Between the Two World Wars,” Slovene studies, No. 1 (2009): 7.

37. Out of nine death sentences pronounced by the fascist Special Court for State Defense, in eight cases the sentences were passed against Slavic irredentists. (See: Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism 1914–1945 (Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), 117).

38. Tone Ferenc, Milica Kacin-Wohinz and Tone Zorn, Slovenci v zamejstvu: Pregled zgodovine 1918–1945 (Ljubljana: Državna založba Slovenije, 1974), 48–51.

39. Milica Kacin-Wohinz, Primorski Slovenci pod Italijansko zasedbo (Maribor, 1972), 313, 314.

40. Milica Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi (Koper: Lipa, 1990), 24.

41. “Talijanski fašisti hoće da osnuju borbenu organizaciju u Splitu,” Pobeda, V, No. 69, date illegible (year 1926).

42. “Lega Nazionale u Šibeniku,” Pobeda, VII, No. 4, 29 January 1927.

43. “Svesni orijunaši na granici u službi Otadžbine,” Pobeda, VI, No. 18, date illegible (year 1926).

44. “Hrvatski borac,” Budućnost, I, No. 3, 30 December 1922.

45. “Poslednji Mohikanci,” Budućnost, I, No. 3, 30 December 1922.

46. “Musolini izmišlja tako zvano Crnogorsko pitanje,” Pobeda, VII, No. 3, 22 December 1927.

47. “Albansko pitanje,” Pobeda, VII, No. 9, date illegible (approximately February–March 1927).

48. “Pred Musolinijev podvig na Balkanu,” Pobeda, VII, No. 10, date illegible (approximately February-March 1927).

49. “Natezanje sa Musolinijem,” Pobeda, VII, No. 29, 29 April 1927.

50. Ljubo Leontić, “Sloboda Jadranskog mora,” Jugoslovenski Jadran – a special ORJUNA publication published on the occasion of its meeting in Dubrovnik on 23 and 24 March 1926.

51. “Italija na Sredozemnom moru,” Vidovdan, VI, No. 397, 22 May 1927.

52. “Musolinijeva agresivnost i naša spoljna politika,” Pobeda, VII, No. 28, 15 July 1927.

53. “Naš prekomorski sused i mi,” Pobeda, V, No. 31, date illegible (year 1925).

54. Boris Mlakar, “Zaton Organizacije jugoslovanskih nacionalistov - Orjune pod budnim očesom italjanskih fašističnih oblasti,” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino, 53, No. 2 (2013): 58.

55. “Protiv rata sa Jugoslavijom,” Vidovdan, II, No. 90, 6 October 1923.

56. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 51, 58, 60, 61.

57. Gligorijević, Organizacija jugoslovenskih nacionalista, 332, 349.

58. Milica Kacin-Wohinz, Narodnoobrambno gibanje primorskih Slovencev v letih 1921–1928 II (Koper: Lipa; Trst: Založništvo tržaškega tiska,1977), 431.

59. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 10 August 1936).

60. The founder and leader of the Yugoslav irredentist organisation TIGR (abbreviation for Trieste-Istria-Gorizia-Rijeka) in Italy. In 1926, TIGR became a part of the ORJUNA border-zone terrorist organisation ORJUNAVIT. In 1931, during the period of dictatorship, Čok formed the organisation Alliance of Yugoslav Emigrant Associations in the Julian March. In the activities of this organisation, Čok relied on the support from Drago Marušić, Ban of the Drava Banovina, a former ORJUNA member and a protégé of the Association of Fighters of Yugoslavia BOJ. At the elections held in 1935, he ran on the electoral list of Bogoljub Jevtić. Due to his engagement in the Yugoslav National Party, the regime of Prime Minister Milan Stojadinović and the Cvetković-Maček government repressed the association of emigrants from the Julian March.

61. SI AS 1931, 935-600-8 document: Političke stranke na Primoriju.

62. Milica Kacin-Wohinz, “Slovenci i Hrvati pod fašističkom Italijom,” Jugoslovenski istorijski časopis, No. 3, (1987): 90.

63. Dorče Sardoč, Tigrova sled: Pričevanje o uporu primorskih ljudi pod fašizmom (Ljubljana, 1983).

64. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 254, 255.

65. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 10 August 1936).

66. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 54, 55.

67. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 20 December 1927).

68. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 10 August 1936).

69. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 20 December 1927). SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 10 August 1936).

70. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Elaborat o Orjuni.

71. Kacin-Wohinz, “Slovenci i Hrvati pod fašističkom Italijom,” 91. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni.

72. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 1 March 1929). SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Predmet ORJUNA.

73. ARS, SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Predmet ORJUNA.

74. Robert Čop, "ORJUNA prototip političke organizacije" (Graduation thesis defended at the Faculty of Social Sciences in Ljubljana, 2006), 72.

75. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 58.

76. Čop, "ORJUNA", 71.

77. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 60, 61.

78. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 13 March 1929).

79. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 52.

80. Later on, during 1930s, the ORJUNA activists also cooperated with the British Secret Intelligence Service. In the wake of World War II, the former ORJUNA intelligence network in Italy and Austria was reorganised and became a part of the National Defense. It intensified its actions and carried out various intelligence tasks, acts of sabotage, and other actions for the British Intelligence Service. (Jerca Vodušek Starič, Slovenski špijoni in SOE 1938–1942 (Ljubljana: samozal., 2002), 111, 112, 143, 150, 161).

81. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Predmet ORJUNA.

82. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 10 August 1936).

83. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 60.

84. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Predmet ORJUNA.

85. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 12 December 1928).

86. АY, fund no. 63, file no. 83/1926, Police report by Police Department in Ljubljana (2 July 1926).

87. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 221–23.

88. CSA, Režimske i reakcionarne organizacije – grupa VII, document No. 858.

89. Ibid.

90. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 5 June 1928).

91. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 245, 246.

92. CSA, Režimske i reakcionarne organizacije – grupa VII, document No. 858.

93. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Kosec Lipe.

94. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 58, 59.

95. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 16 October 1928).

96. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 4 April 1929).

97. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 354.

98. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 25 January 1929).

99. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 22 January 1929).

100. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 26 January 1929).

101. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 1 February 1929).

102. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 29 March 1929).

103. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 9 March 1929).

104. Due to the repressive measures taken by the Italian authorities in reaction to the armed attacks launched by the ORJUNA and TIGR in the period from 1922 to 1931, more than two thousand members of the Slovenian ethnic minority were forced to leave Italy. In order to maintain good relations with Italy, the Yugoslav government resettled most of these emigrants in the region of Bistrenica in Macedonia, with the aim of preventing them from taking part in any further armed actions of the ORJUNA. (Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 280, 316, 317, 329, 230).

105. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 10 August 1936).

106. Following Kukec’s death, the operational leadership of the irredentist ORJUNA organisation in Italy was taken over by Lipe Kosec. (Vodušek Starič, Slovenski špijoni in SOE, 114).

107. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 301, 302.

108. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Materijal goričke kvestre o Orjuni (report dated 12 October 1929).

109. Kacin-Wohinz, Prvi antifašizem v Evropi, 356.

110. SI AS 1931, 935-600-12 document: Elaborat o ORJUNI.

111. “Balkanske stvari,” Vidovdan, V, No. 322, 28 February 1926.

112. Ferenc, Kacin-Wohinz in Zorn, Slovenci v zamejstvu, 139.

113. Jurij Perovšek, V zaželjeni deželi: slovenska izkušnja s Kraljevino SHS/Jugoslavijo 1918–1941 (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2009), 72–74.

114. “Diplomacija iredentizma,” Pobeda, I, No. 7, 24 September 1921.

115. “Beč i Beograd,” Budućnost, II, No. 9, 3 March 1923.

116. Ljubo Leontić, “Govor Predsednika Direktorijuma brata Leomtića,” Pobeda, V, No. 40, date illegible.

117. “Koruška,” Pobeda, V, No. 66, date illegible.

118. “Orjunaši u Koruškoj,” Pobeda, V, No. 78, date illegible.

119. “Obnavljanje nemčurstva v severni Sloveniji,” Orjuna, I, No. 30, 15 July 1923.

120. France Filipič, “Nekaterne značilnosti delavskega revolucionarnega gibanja v Mariboru in njegovem zaledju v letih 1921–1925,” Revolucionarno delavsko gibanje v Sloveniji v letih 1921–1924: Referati z znanstvenega posvetovanja v Ljubljani 6. in 7. junija 1974 (Ljubljana, 1975), 151–73.

121. “Spominski shod za Koroško u Mariboru,” Orjuna, II, No. 51, 18 October 1924.

122. CSA, Režimske i reakcionarne organizacije – grupa VII, document No. 855.