The Border River Phenomenon: the Example of the River Mura*

UDC: 341.222(282.24Mura)"1918/2004"

IZVLEČEK

FENOMEN MEJNA REKA: PRIMER MURE

1Avtor analizira dva vidika dolgega trajanja fenomena mejne reke na primeru reke Mure: a) razmerje med rečno strugo, mejno črto in antropogenimi učinki na reko; b) odkrivanje historičnih struktur skozi perspektivo mejnih sporov. “Zdravorazumsko” razumevanje mejnih rek predpostavlja ujemanje reke in mejne črte. Kljub temu je lahko v pokrajini in v kartografskih reprezentacijah velika razlika med tema dvema elementoma.

2Ključne besede: mejne reke, Mura, okoljska zgodovina, rečne regulacije, mejni spori

ABSTRACT

1The Author analyses two long-term aspects of the border river phenomenon with the example of the river Mura: a) the relationship between the river bed, the boundaryline, and the anthropogenic effects on the river; b) discovering the historical structures through the perspective of border disputes. The "common sense" ideas about border rivers imply that the river bed and the boundaryline usually match. However, in the actual landscape and cartographic representations, the differences between these elements can be significant.

2Key words: Border rivers, River Mura, Environmental History, River regulations, Border Disputes

1.

1Rivers were not invented by people. They are natural phenomena with their own dynamics, and can never be completely controlled. However, border rivers are different: they are social and political concepts that people "assign" to natural rivers. The basic goal of the project entitled "The Border River Phenomenon" has been to explore the relationship between "natural" rivers and the concept of border rivers, using selected examples. According to their classic sociological definition,1 borders are not a spatial fact with social effects, but a social fact manifesting itself in the space. Borders have a twofold character: they are a consequence of historical and political processes as well as originators of social order.2 Border rivers are a social fact as well, but they are essentially defined by "natural" rivers. Due to natural fluvial processes (changing river beds, floods, drying up), border rivers function "on their own", "speak for themselves", and their "activities" have social consequences. On the other hand, human activities influence rivers as well. In the article we will analyse two long-term aspects of the border river phenomenon with the example of the river Mura:

- the relationship between the river bed, the boundaryline, and the anthropogenic effects on the river;

- discovering the historical structures through the perspective of border disputes.

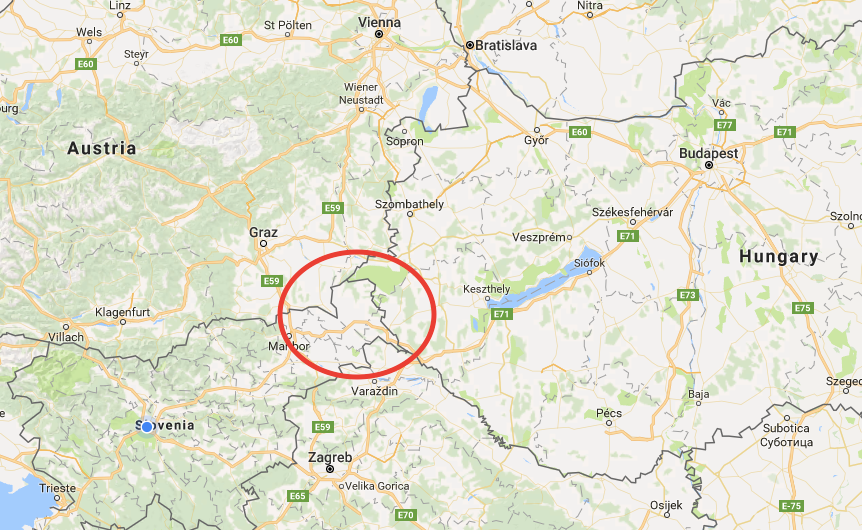

1Source: www.google/maps (November 16, 2017)

2. The Relationship Between the River Bed, the Boundaryline, and the Anthropogenic Effects on the River

1The "common‑sense" ideas about border rivers imply that the river bed and the boundaryline usually match. However, in the actual landscape and cartographic representations, the differences between these elements can be significant. The elements are mutually dependent: boundarylines are usually defined on the basis of the river beds. In turn, boundarylines may also influence the river beds (human activities on the river). Due to meandering and erosion, the river does not "stick" to the river bed as "captured" by the cartographers/geodesists in a certain historical moment. Boundarylines may also change due to political/administrative changes.

2The proximity of rivers calls for certain human activities. In case of border rivers, these activities become even more complicated: who has the jurisdiction to build there? Who finances the works? Who carries them out? Such activities require communication and coordination between the two entities, separated by the river. We can notice an interesting rule in the interaction between people and rivers: the rivers that are prone to changing their river beds often due to hydrological and geomorphological characteristics (meandering, dead river beds, gravel bars) – which means that they are active "in themselves" – call for a more significant human response than the rivers with relatively stable river beds. In case of border rivers we can underline an additional phenomenon. By changing its river bed often, a border river can cause political problems at the level of the two entities it separates. The regulation of such a river calls for the cooperation of both sides, which involves the coordination of works and expenses. Due to the problems with coordination and financing, the authorities from both sides frequently delay the works at the detriment of the population on both sides of the border. The history of river regulation is also exceedingly significant in the cases where the river has only recently gained the status of a border river. In such cases the history of regulations may be deemed as typical administrative legacy.

3The history of the river Mura is truly fascinating – in the sense of environmental history as well as regarding the delimitation of political entities. It is not remarkable in any way that many different disciplines have often focused on Mura and its history: political history, environmental history, various fields of geography, cartography, and hydrology. Due to the hydrological characteristics and lowlands environment, the downstream part of Mura has always kept changing. Mura is a part of the Black Sea drainage basin, a left‑bank tributary of the river Drava. It is a snow‑fed river system and belongs among lowland rivers, characterised by frequent river bed changes on the flood plains, meandering, and frequent floods (the frequency and scope of floods have been anthropogenically reduced by means of several hydro‑accumulation dams even before this river reaches Slovenia). In its totality, Mura is 465 kilometres long. It flows through Slovenia in the total length of 95 kilometres, and the section of the Slovenian "internal" Mura is approximately 33 kilometres long.3 Mura represents borders in the total distance of 115 km (25 % of the whole river). First it divides Slovenia and Austria between the villages of Ceršak and Petanjci (in the distance of over 33 km); then Slovenia and Croatia between Gibina and Krka (almost 34 km); and finally, Hungary and Croatia in the distance of 48 km between Krka and until it flows into the river Drava.4 This contribution will focus on three sections: the border river Mura between Slovenia and Austria; the Slovenian "internal" Mura; and the border river Mura between Slovenia and Croatia.

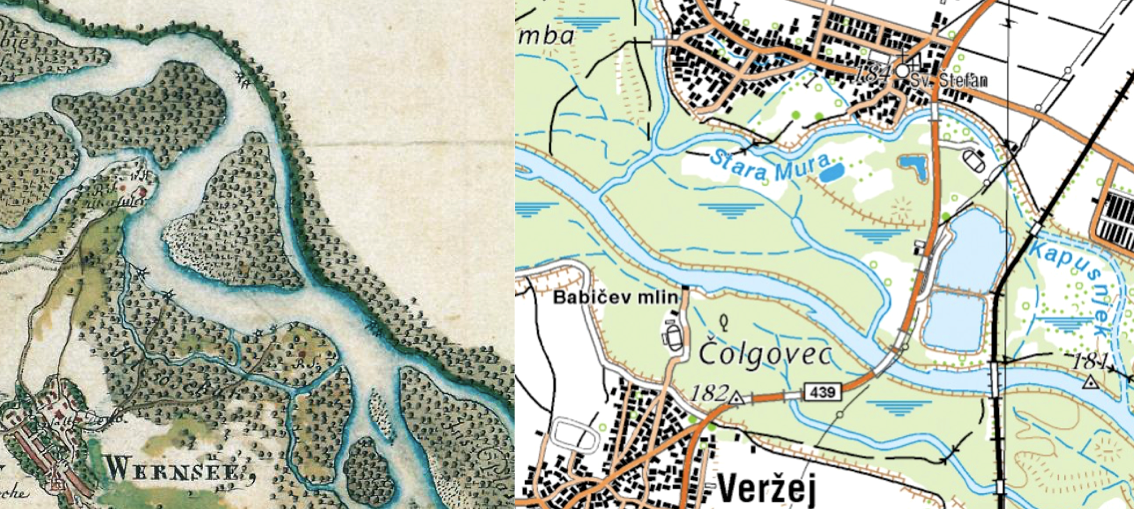

1Source: www.geopedia.si (November 16, 2017)

4In the language of political history, Mura's main characteristic could be described as "movement". However, the expression is not precise enough. Throughout its history, Mura has been creating new river beds and branches. Hydrologists describe it as a type of a meandering braided river, whose channel typically consists of a network of small channels. The majority of it does flow through its main river bed, but its diversion results in new main channels, while the old main channels turn into side channels.5 Mura does not only "move", but keeps changing its form as well. What was the cohabitation of the river and the people like in the circumstances before the modernisation processes? The unpredictable nature of the river impeded any permanent cultivation of the area by the river. For example, between the 15th and the 19th century, a large area of fallow land was created between the towns of Šentilj and Radgona, supposedly resulting predominantly from the untameable nature of the river. By the early modern period, the river Mura had shaped a large island between two of its branches, where the fortified border town of Radgona with its extensive fortification system and two strategically important bridges developed. According to the historian Hozjan, south of Radgona the river kept creating many new branches, and the Josephine maps reveal all sorts of river bed changes.6 The rate of flow ratio was supposedly, according to the Josephine maps, 40 % of water in the main channel versus 60 % of water in the branch.7 For centuries, the small Prekmurje region village of Dolnja Bistrica had been developing some distance away from the river bed. However, by the late 18th century Mura captured it into a U-shaped channel.8 According to hydrologists, in the Middle Ages the river's basin kept changing in case of high water in the north, and Mura even destroyed a few villages in the Apaško polje plains.9

5Until 1918, the section of Mura between Radgona and Gibina was a border river, while from Gibina to its mouth it was Hungarian. Regarding the issue at hand, we are especially interested in the fact that any human intervention in the river bed or river banks, no matter how small, was related to the border river political concept. Hydrological literature places the first unsystematic measures addressing the river's water regime management into the 16th century. Their goal was to protect the settlements and allow for the navigation of the river Mura. Since the late Middle Ages, Mura has had the greatest transport potential of all the Styrian rivers. In the early modern period, the centres of rafting on Mura were located in Ernovž, Cmurek, and Radgona. On the Hungarian side, legislation on securing the banks in order to protect the local settlements was already in force in the 17th century. In the first period of early modernisation – the Theresian period – Mura's river bed was surveyed (1753). On the basis of these surveys, a few meanders were shortened and the river banks secured.10

6In this period, the nascent Habsburg state was mostly interested in managing river navigation rather than in the border function of Mura. The planned river management with the aim of ensuring navigation began in 1770, when a special commission inspected the river bed. The works were overseen by Gabrijel Gruber, a Jesuit from Ljubljana, while the future mathematician Jurij Vega participated in the project as well. The thorough regulation of the river Mura could only be implemented at the section before Radgona.11 In 1799 the areas by the river were visited by a special bilateral commission with a geometer, which drew up plans to regulate the flow of Mura from Dokležovje to Veržej and Dolnja Bistrica. However, the plans fell through due to the Napoleonic Wars. The Hungarian and Styrian commissioners specified precisely which embankments and channels would be constructed by Styria and which by Hungary (the Zala County). The document summed up by Ivan Zelko reveals that the planned undertaking called for extensive coordination of the two political entities. Styrians were also supposed to carry out the construction in the Hungarian territory and vice versa.12

7In 1810 the meander near Razkrižje was shortened in order to protect the settlement from the annual floods. In 1822 Mura created a new water channel near Mursko Središče. Thus the bridge found itself on dry land and regulation was necessary in order to steer Mura back to its old river bed. The construction of the Ledava – Krka relief channel and the relocation of the mouth of Krka's tributary Ledava around 1850 were important as well. In the second half of the 19th century, large-scale regulation took place. In 1874 the government in Vienna adopted a decision to finance the regulation of three sections of the river Mura between Graz and Cven (the so-called Hohenburg Regulation 1874 – 1891). The majority of the works took place at the section between Graz and Wildon as well as between Wildon and Radgona.13 The expenses of the ambitions construction projects were shared by the central government (40 %), the province of Styria (40 %), and the district administrations between Graz and Ljutomer (10 %).14 During these works (between 1878 and 1879), high water and damage in the sections that had not yet been regulated occurred. The regulation was strengthened and expanded to other sections as well, but the works at the section bordering on Hungary were carried out very sparsely. The reasons for the Hungarian diminished interest in what was then its border river were closely connected with the border status of this section of the river. According to the Slovenski gospodar newspaper, on 8 October 1878 the Styrian Provincial Diet demanded that the government in Vienna persuade the Hungarian government "to take part in the joint regulation of the river Mura at the Styrian-Hungarian border.”15

1Sources: Rajšp, Vinko et al. (eds.). Slovenija na vojaškem zemljevidu 1763–1787. Band 6. Ljubljana, 2000; www.geopedia.si (November 16, 2017).

8In the beginning of the 20thcentury, the local large estate owners at the Hungarian side of Mura organised themselves and established a river cooperative in Lendava in 1901. The cooperative was supposed to address the water management problems in certain parts of the Zala County. It drew up plans for the regulation of streams and draining of certain areas, but the Zala County did not give its concession for the construction works until as late as 1907. The cooperative was supposed to broaden the river bed of Ledava and maintain the conditions of the following streams: Ledava, Krka, Kobiljski potok, Bukovnica, Libenica, Črnec, Lipnica, and Bogojinski potok. With the dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1918, the works at the river Mura stopped. Due to the abandonment of maintenance works at the section between Špilj and Radgona (after 1919 the new border between the Republic of Austria and the Kingdom of SHS), certain sections of Mura broadened significantly (up to 200 metres). Due to the neglect of its banks, Mura flooded several times between 1918 and 1926 (Bunčani, Veržej, Dokležovje, Melinci). The interwar period authorities only undertook the regulation works at the (new) internal section of Mura after the catastrophic floods.16 On 12 November 1925, Ledava and Kučnica flooded Murska Sobota. In just a few hours, the city transformed into a "Prekmurje Venice", and the homes of almost a third of its citizens were destroyed.17 Due to the poor state of Mura's river bed, the Interstate Commission for the Regulation of Mura was established in Maribor in 1926. It was tasked with managing all of the works at the (border) river. The states agreed that each of them would restore the extensive embankments on their respective banks of the border river Mura, while they would share the expenses for the works required at the river bed itself. The works were concluded in 1937/38, and since then Mura's rate of flow has increased significantly.18

9A few fortification works at the (internal) river Mura were carried out in 1928, while between 1936 and 1938 it was regulated between Sladki vrh and Apače. Despite everything, the 1938 floods were catastrophic. Mura engulfed more than 40 villages on both sides, almost flooding the entire Mursko polje plains. In light of this disaster, the Prekmurje correspondent of the Slovenski gospodar newspaper complained that the authorities neglected the Prekmurje region, and that Mura should have been systematically regulated a long time ago. He also underlined that the inhabitants of Prekmurje could see clearly how Austria assisted the victims of the floods in its territory, and that "this certainly does not contribute to national awareness".19 After these floods, the authorities established an action committee tasked with ensuring a comprehensive protection of the area by constructing embankments along a lengthy section of the river. However, World War II started before any construction works even began. The period of the socialist Yugoslavia was the time of the most significant investments into the water infrastructure in the Pomurje region. We should also mention the construction of the dry relief channel Ledava-Mura, constructed in order to prevent floods in Murska Sobota (the works were initiated in 1948 and completed in 1958). The other tributaries of the river Mura were gradually regulated and dammed as well. In 1966 the regulation of the border river Kučnica began in cooperation with Austria. The expropriation, replacement of land plots, and new definition of the boundaryline were carried out as well.20 At this point we do not have enough space to list all of the regulation works in this period. In short, by 1985 the river Ledava had been completely regulated (the section bordering on Hungary was not regulated until as late as 1997). Due to occasional flooding (for example in 1972), experts supported the finding that in addition to strengthening the river bank, accumulations and dry reservoirs should be constructed on both sides of the river Mura as well. Until the end of the 1980s, three accumulations (lakes) and a single dry reservoir were constructed on each side of Mura.21

10By the dissolution of the common state, the Pomurje region had become, in the sense of its watercourses, a completely artificially-regulated landscape with channels, embankments, and artificial lakes that had not existed previously. The secondary river branches and marshes had largely disappeared from the landscape. The estimate that the geographical character of the landscape has changed most profoundly precisely due to watercourse regulation is not an exaggeration. However, human interventions into the nature of the river Mura and its tributaries have also resulted in unforeseen consequences. In the period of the so-called "natural" Mura, the width of the river and its secondary river beds reached up to 1.2 km, but it was narrowed to as little as 60 – 80 metres by means of hydrological interventions. These processes have resulted in a greater speed of the river and a more significant power of erosion. Due to the fortified banks, the erosion power of the river cannot be distributed throughout its bed: instead all of the energy goes toward deepening the river bed.22 Consequently the groundwater level in the whole Mura drainage basin is decreasing, the groves by the river are drying out, and the drinking water reserves are diminishing.23 In the study ordered by the Permanent Slovenian-Austrian Commission for Mura, the experts proposed the following measures in 2001: widening the basin of the border river Mura to 200 metres; constructing side branches (or restoring the old ones); and adding gravel.24 These measures can thus be interpreted as the very opposite of the interventions in the 19th and 20th century. From the viewpoint of environmental history, the example of Mura is interesting because of the relationship between the river and human interventions in the long run: if repeated attempts had been made to "capture" Mura into a single fortified river bed for more than three centuries (and regulate its unpredictable tributaries), in the last few decades measures have been initiated to undertake a (limited) reconstruction of the pre-regulation conditions.25

1Source: G Mayr: Südliches Steyermark. Illyrian, Friaul. Küstenland. Gotha 1872.

11According to the findings of hydrologists, after World War II the maintenance and construction works at the basin of the river Mura where it borders on Austria have been most thorough, while they have been less intensive at the river's internal sections and where it borders on Croatia.26 At the Slovenian-Croatian border, the river is – in comparison with the section bordering on Austria – still quite natural and belongs among moderately altered watercourses, while a few sections at this part of the river have been regulated as well, due to the danger of flooding.27 The extensive works aimed at systematically regulating the river in the territory of Slovenia were carried out between 1972 and 1990, up to the town of Bakovci. At a part of the river Mura, located downstream from Mursko Središće (at the border between Croatia and Slovenia), individual meanders have been separated from the main river bed.28 The main works (canals) were carried out from the 1960s and until as late as 1990. The works were carried out by Slovenia and Croatia, jointly and in accordance with the 50:50 system, regardless of the cadastral border. Hydrologists should supposedly observe the rule that the left bank is Slovenian and the right bank is Croatian.29 The Final Award of the Arbitral Tribunal (of 29 June 2017) also quotes a 1967 document mentioning the project of regulating Mura with channels near Hotiza.30

12Rivers as transnational natural phenomena with their unpredictable "lives" tend to force political entities to engage in long-term cooperation. We have already mentioned the first permanent bilateral commission between Austria and the Kingdom of SHS/Yugoslavia, established in 1926. On 16 December 1954, the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia signed the agreement on the establishment of a permanent bilateral commission for the river Mura, and ratified it in 1956. The commission was tasked with the joint investigation and resolution of water management issues, implementation of measures, and realisation of works at the border section of Mura and its branches due to pollution and drainage of water from the river. After it attained independence, the Republic of Slovenia ratified this agreement in 1993.31 It is relevant for the contemporary history of the border river Mura that after their independence, Croatia and Slovenia have not formed any dedicated bilateral commissions for this river. However, they did indeed agree (in 1996) to establish a Permanent Slovenian-Croatian Commission for Water Management. The rules on the activities of this Commission were not ratified by the two states until as late as 1998.32 The sub-commission for Mura operates in the context of this Commission as well.

3. Discovering Historical Structures Through Border Disputes

1How can we "discern" the role and changes of the political structures from the example of border rivers? Documents about border disputes represent an excellent source for analysing the relations between the state structures and the situation "in the field". Border river disputes can drag on for several centuries. In order to solve the current border disputes, it is especially important to understand the rich pre‑history (a part of the border rivers' administrative legacy). River border disputes can also "become obsolete" and calm down due to altered circumstances, or can also be created anew as a river acquires the status of a border river.

2At the river Mura between the towns of Radgona and Ljutomer, the border between the German part of the Roman Empire or Styria and Hungary had been settled by the middle of the 13th century, in so far as that was possible in the medieval circumstances.33 In the published medieval sources and older historiography we can find several reports on the river Mura border disputes. A more detailed analysis of these disputes reveals that one of the reasons for the disputes was the combination of this river's twofold role: Mura as a medieval border river (in view of the nature of the river, this border could only possess a zoning character); and Mura as an economic and geographic factor. The first recorded border dispute at the river Mura proves that the medieval actors would also use the natural might of the river for strategic and military purposes. If the border at the river Mura was relatively calm at the turn of the 12th century (at this time permanent settlements were developing there), after 1233 the border disputes reignited for a little while. In that year the Hungarian army invaded Styria, but it soon retreated. Judging from the Hungarian archive resources, Styrians supposedly used the tactics of flooding the river. They dammed the river Mura, and the water flooded several villages on the Hungarian side. The situation was remedied by a Hungarian dignitary who tore down the dam and restored the previous conditions.34

3In the first half of the 16th century, disputes between the inhabitants of the two river banks would often arise due to Mura's inconstant flow. Tomaž Széchy, a landowner with land holdings in Gornja Lendava and Murska Sobota, attempted to protect his extensive properties in the Prekmurje region by constructing two river beds on his side, steering the flow of Mura towards the Styrian side. There the river started eroding the fertile land and getting closer to the settlements.35 The Styrian imperial representative contacted the Hungarian feudal landowner, who was unwilling to negotiate. In 1511 the Styrian side decided to implement unilateral measures. It deployed an engineer and his team of workers to the river Mura in order to construct a dam that would benefit Styria. After a few days Széchy attacked them, scattering the workers and imprisoning the engineer. Széchy's people strengthened the embankments even further, and due to the rushing river several fields and even a few villages on the right bank of Mura disappeared. When the Styrian provincial government once again sent its commissioners to the river in 1524, Széchy fired on them with cannons and rifles. The Styrian subjects attempted to fortify the river bank on their own, but the "Hungarians" would not allow them to drive stakes into the river. Anton Banffy, owner of land holdings in Dolnja Lendava, would allegedly behave in a similar manner. The disputes continued; various commissions would meet unsuccessfully; but nothing changed in the field. In 1537 Styrians excavated several ditches under military protection in order to prevent Mura from doing so much damage. However, Széchy's successor Aleksij Thurzo ordered that the ditches be buried immediately. Already next year the Hungarian lord once again repaired the embankments to his own benefit. When Styrians attempted to remedy the situation in 1539, armed conflicts broke out, and according to Kovačič "a Hungarian tax collector, who agitated the people, was thrown into the river Mura with his arms and legs bound". The disputes could not be appeased. Bloody skirmishes kept occurring, and year after year "bloody robbery and violence was reported". Nevertheless, towards the end of the 16th century the conflicts gradually cooled down.36

4According to Kovačič, it could also happen that Mura itself would remedy what "Hungarians took from Styrians unjustly". Towards the end of the 17th century, Mura changed its flow yet again. The inhabitants of the Styrian village of Hrastje acquired a bit of territory that they started using as grazing grounds. In the middle of the 18th century, attempts were made to take away the villagers' right to grazing, and therefore they complained to the provincial authorities. According to the older Slovenian historiography, the border between Hungary and Styria was supposedly settled in 1755, during the Theresian consolidation of the Habsburg Empire, especially in the upper part of the river Mura between Radgona and Mota.37 The subjects built dams and placed border stones in order to mark the border between the political entities. The latter would often be removed by the river, which kept flooding. However, according to Fran Kovačič, after this regulation major border disputes no longer occurred.38 In the 19th century, Mura became a "solid" state border for a short time, in 1848 and 1849, when the revolutionary Hungary achieved significant autonomy in its relations with Vienna. This was followed by a reaction from the Habsburg Court.39 On 11 September 1848, the Habsburg General and Croatian Ban Jelačić invaded Hungary over the river Drava near Varaždin and proceeded into the territory of Zala County, which included the south-eastern part of the Prekmurje region. On the same day the members of the Zala County National Guard burned the bridge over Mura near Lendava. On the basis of the memoirs of a Hungarian National Guard member we can identify the basic characteristics of the bridge that was destroyed by the defenders. The straw ropes, covered in an abundance of tar beforehand, were set on fire. As it was windy, the fire simply "devoured the dry planks and beams".40

5In the tumultuous times of the establishment of new states in the Central Europe and the formation of new state borders between 1918 and 1920, the status of the border at the river Mura changed a few times. On 12 August 1919, the Army of the Kingdom of SHS occupied the Prekmurje region, and this territory on the left bank of Mura was finally annexed to the Yugoslav state with the Treaty of Trianon (4 June 1920). It is interesting that during the occupation (between August 1919 and June 1920), the border at Mura was not abolished, but rather even strengthened. The passage of the inhabitants of Prekmurje over Mura was only possible with permits. In the autumn of 1920, Prekmurje was still a closed territory, and the Prekmurje press complained that soldiers would not let people cross Mura without the permits that were difficult to obtain.41 At the same time, the Hungarian authorities attempted to emphasise the significance of the border on the river Mura. On 15 April 1921, the Zala County lodged a complaint against the secession of the territories by the river. They emphasised that Mura was a broad and quick river that separated the villages on both sides "like the Great Wall of China". The inhabitants of the two river banks did not know each other, nor did they cooperate or trade. They also emphasised the fact that there were not any bridges across Mura throughout the whole border, from Radgona to Mursko središče.42

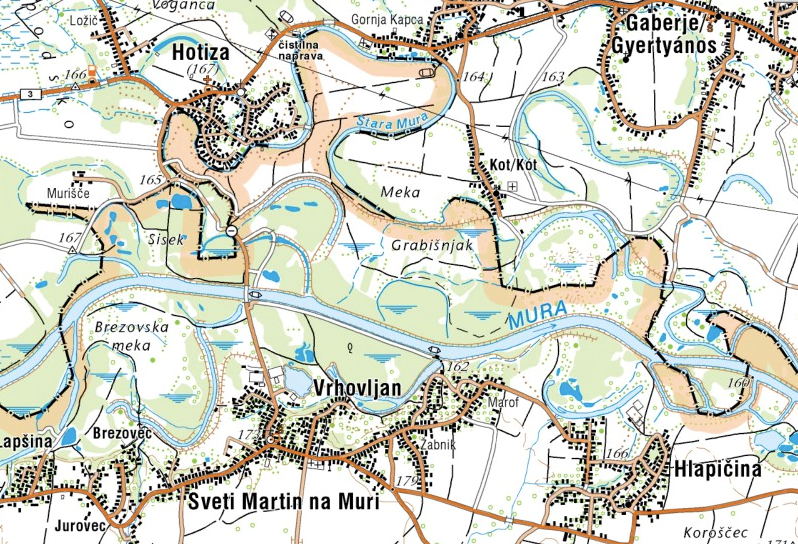

1Source: www.geopedia.si (November 16, 2017).

6The National Government in Ljubljana was well-aware of this. On 13 October 1919, the Commissioner of Social Welfare reported to Ljubljana that the only road connection with Prekmurje was the bridge in Radgona, which, however, now belonged to the Republic of Austria.43 The Slovenian political elite strived to ensure that the bridge over Mura near Veržej would be built as soon as possible, even though complications kept arising regarding the financing of the construction works.44 The Veržej bridge was opened solemnly on 23 April 1922.45 That the opening was related to the former border river status is also proven by the fact that the members of the Yugoslav-Austrian and Yugoslav-Hungarian delimitation commissions were invited to the event.46

7While the processes of approximation were underway at the former border section of the river Mura, at the new Austrian-Yugoslav border disputes and difficulties with the delimitation kept arising. The new state border at the river Mura between Cmurek and Radgona weighed heavily on the peasants between Drava and Mura. Until the end of 1921, the Yugoslav authorities allowed access to mills and saws at the border river, but in the beginning of 1922 the customs services prohibited the access. After the intervention of the Slovenian Members of Parliament in Belgrade, the access to the aforementioned mills and saws was included in the agreement on the frontier-zone traffic with the Republic of Austria.47 The paths that the local population could use to cross the border due to economic reasons or in emergencies were specified. Newspapers urged people not to transport prohibited goods across the Mura border: "Should smuggling start occurring at the border, the government will, as it has already threatened, immediately put a stop to the whole frontier-zone traffic. In such a case it would be very difficult to restore the current concessions".48 The next bridge over Mura, near Radenci, was not open until as late as 1940.49

8During the period of World War II (1941–45), Prekmurje was reannexed to Hungary, and subsequently (after the Soviet occupation and the arrival of the Yugoslav forces) to Yugoslavia or the People's Republic of Slovenia.50 The river Mura between Gibina and the triple border with Hungary may have indeed received the status of a border between two Yugoslav federal units (People's Republic of Slovenia and People's Republic of Croatia). However, no disputes regarding the border at the river Mura took place in the post-war period. It is interesting that the biggest border dispute between Slovenia and Croatia after World War II took place in the vicinity of Mura. The conflict occurred in the former Štrigova municipality, the only part of Međimurje that had been included in the "Slovenian" Drava Banate after the administrative reorganisation of 1929. After 1945, however, this territory was annexed to Croatia. Regardless of the dimensions of the dispute (people would also express their discontent with petitions and gatherings) and the proximity of the villages involved, the river Mura did not play any role in this particular border dispute.51

9In the period between 1945 and 1991, Mura did not "actively" appear in the international (or inter-republican) disputes. The nature of the border between two Yugoslav federal units did not call for a precise demarcation or division of jurisdiction. However, with the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991, the relations in the Slovenia – Mura – Croatia triangle once again became complicated. The problem of the so-called twofold ownership appeared by the Slovenian-Croatian border at the river Mura, which had remained in the background before the emancipation of both of the states involved, even though even in the Yugoslav period there had been differences between the taxation of property in Croatia and Slovenia. In 1992, in the Lendava municipality, 2963 landowners from Croatia owned 805 hectares of land or 3.1 % of the territory. On the other hand, around 800 landowners from the Lendava municipality – most of them from Hotiza – owned land in Croatia as well.52 Near the Slovenian village of Hotiza, the border between the Slovenian and Croatian cadastre is furthest away from Mura, and therefore the considerable number of land property owners in Croatia is not surprising. The cadastral border between the states follows the river as it was identified by the creators of the Hungarian cadastral measurements in the 19th century. Since then the river has changed its flow considerably, while the cadastral municipality borders have remained in the ongoing administration of both states as the Habsburg administrative legacy.

10It is important for the future development of the events that the equalisation of the Slovenian-Croatian border and the cadastral border took place rather late. The border between Slovenia and Croatia might have had an administrative and state-legal character (the Yugoslav republics were defined as "states"). However, in the field the boundaryline was not defined precisely until as late as 1980. In 1980, the legislation on municipalities changed in Slovenia, and now set out that the territories of the municipalities should correspond to the cadastral municipalities. As the border between Slovenia and Croatia had been defined descriptively as the border between the Slovenian and Croatian municipalities, the border between the Slovenian and Croatian cadastres de facto became the Slovenian-Croatian boundaryline. In the first years of independence, Slovenian geodesists underlined that the border according to cadastral municipalities "will not be functional and prudent", and saw bilateral harmonisation with the assistance of joint commissions as the right way of defining the border.53

11The discrepancies between the cadastral border and Mura's river bed paved the way for the border incidents near Hotiza in 2006. Despite the multiple attempts at specifying the border between the states (e.g. the efforts of joint commissions between 1993 and 1998 and the so-called "Drnovšek-Račan Agreement" of 2001), the Slovenian-Croatian border at the river Mura in 2006 was just as vague as in 1991.54 The series of incidents began already in May 2005, when the Croatian authorities confiscated a river Mura ferry, owned by the inhabitants of Hotiza (internet 1). In March 2005, the Croatian side started building a bridge across Mura without any agreement with Slovenia, and did not open it for traffic until as late as the summer of 2006, due to high water. Because of the bridge, the Slovenian authorities protested more than once. According to the opinion of the Slovenian water experts, the bridge worsened the local flood safety.55

12The considerable flooding potential of the river Mura and the importance of flood protection embankments represented an important environmental and historical factor in this story.56 In August 2005 Mura flooded, and it turned out that new embankments should be constructed on both banks of the river in order to improve flood safety. However, who would be building in the territory under dispute? Before 1991 it was the Slovenian side that would traditionally build embankments on the left bank of Mura. Slovenian institutions started constructing the embankments, but only in the territory of the Slovenian cadastre.57 Towards the end of August 2006, the Croatian side started building embankments on the left bank of Mura (in the Croatian cadastre) without asking the Slovenian government for permission. The developments near Hotiza attained significant media dimensions. In Slovenia, the territory around Hotiza suddenly became a matter of national interest. After the meeting of both Prime Ministers in the disputed territory on 2 September 2006, an agreement was reached on the joint construction of embankments at the river Mura, and the issue temporarily vanished from the media. Not for long, though. The border dispute culminated on 13 September 2006, when the Croatian police detained a few Slovenian journalists due to their alleged illegal crossing of the state border. The Slovenian authorities reacted immediately and demonstrated force, deploying a fully-outfitted special police unit at the border.58 The Slovenian police lined up at the cadastral border and crossed it as well. They dug up the newly-constructed road and brought down two trees on it. This was a road within the borders of the Croatian cadastre, linking the hamlet of Murišče with the Croatian side. The miniscule settlement with nine inhabitants was caught in the "limbo" of the Slovenian-Croatian dispute. The hamlet has been entered into the Slovenian Register of Spatial Units, but within the Croatian cadastre.59 The conflict was appeased after the agreement of the Slovenian-Croatian Commission for Water Management of 15 September 2006 on the joint restoration of the high-water embankment Kot-Hotiza on the left bank of Mura.60

13There is no room here for an additional historical discourse analysis of the dispute. However, a short media analysis of the conflict by the border river Mura in 2006 indicates the importance of the representations of border rivers in various environments. Judging from the Croatian response, Croatia completely equalised the state border with the cadastral border. Meanwhile, for the Slovenian leadership the cadastral border represented merely one of the criteria for defining the borders in the future. While the Croatian media reported on the cadastre as the indisputable border between the states,61 the Slovenian press would relativise the cadastral border. The correspondent of the Dnevnik newspaper claimed that the disputed territory may well have been a part of the Croatian cadastre, but that it was nevertheless "sovereign Slovenian territory".62 The Slovenian media would not clarify the complex circumstances by the border river until the dispute escalated extremely and the police forces of both states were staring down the barrels of their guns.63

14The activities of the permanent inter-state bodies, which usually take place in the background, became inseparable from national interests. Only studying the border river discourse allows for the understanding of the relations at the landscape–politics–ideology level, and it especially has a role in comprehending the mechanisms of nationalist delimitation. Landscape changes (the movement of the river, flooding) call for measures to be implemented by both entities. This is exploited by various political groups that are looking to further their interests, and at the level of ideology and representations various media discourses, involved in the reporting/reflecting on the border dispute, are established. Even the mere choice of words can have a decisive impact on the main message: is this a cadastral border or a state border? In media discourses, however, particularly the outrage and feelings of endangerment tend to come to the forefront. If the Slovenian media were appalled at the Croatian construction projects on the left bank of Mura, then the Croatian media were horrified because of the presence of the Slovenian police in the territory of the Croatian cadastre. On the other hand, the media critical of nationalism and the contemporaneous leadership were indignant at the border disputes in general as well as at the demonstration of force.64 Meanwhile, the British BBC asked itself (in line with orientalist stereotypes) whether a new war might break out in the Balkans.65

15The political elites solved the issue by signing the Arbitration Agreement regarding the border in November 2009. Both governments submitted their territorial and maritime disputes to arbitration. The Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague was chosen as the arbitral institution.66 The Court of Arbitration announced its Final Award on 29 June 2017. However, at the time when this contribution was written, Croatia did not acknowledge the Final Award due to the 2015 audio surveillance scandal involving a Slovenian arbitrator. How did the Court of Arbitration solve the border dispute on the river Mura that had escalated in 2006? Generally it adhered to the cadastral border, with the exception of the aforementioned hamlet of Murišče, which went to Slovenia. The Slovenian interpretations of Mura as the Slovenian-Croatian border river were not successful. The Slovenian side counted predominantly on the division of administrative units in the period of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the fact that the left bank of Mura had been in the hands of the Slovenian side until as late as 1991.67

4. Conclusion

1The "longue durée" border river status indirectly affects the shape and dynamics of the river bed. In the time when Mura represented the border between the Austrian and Hungarian parts of the Habsburg Empire (in various forms ever since the late 18th century), the "internal" Austrian part of the river was regulated, while the section of Mura bordering on Hungary was neglected. In the historical press we can come across several reports on the demands of the Styrian province that the central (Austrian) government in Vienna should demand that Hungary co-finance the regulation works at the border river Mura (the today's Slovenian "internal" Mura). At the same time, the Hungarian side took its own initiatives to regulate the river and its tributaries. After 1918, a different dynamics became noticeable. The section of the river at the Yugoslav-Austrian border was well-maintained (joint commission after 1926), while its internal part between Styria and Prekmurje was neglected (i.e., works would only be initiated after catastrophic floods). In the period after World War II, the section of Mura bordering on Austria was still the best-maintained part of the river, while significant improvement of regulation works was also noticeable at the internal Mura and at the section bordering on Croatia, as the border between the republics did not impede them. As Mura moved from the cadastral borders, the left‑bank flood protection embankments were also constructed in the territory of Croatian cadastral municipalities, for example near Hotiza and Petišovci. Until 1991 the rule was that both states had to take care of their respective banks, regardless of the location of the cadastral border. However, since the border in the area of Hotiza had not been defined, after the emancipation of Slovenia and Croatia conflicts arose with regard to the administrative jurisdiction.

2Who, then, is responsible for the 2006 border dispute? The answer is simple: the river Mura, which has its own life and refuses to stick to its river bed. The history of border disputes points out the difficult relationship between the river in the landscape and the borders. All the sections of Mura that we have analysed in this contribution had the status of a border river in certain periods of time. From the longue durée perspective, we can establish that the border disputes by the river Mura took place in two periods: in the Middle Ages / early modern period; and in the contemporary history. Could we propose a hypothesis that border disputes tend to arise when the constellations of the political spaces and borders are not specified? Our findings do support this, even though this interaction cannot be completely proved. However, we can definitely underline the significant importance of administrative legacy. We can also apply the concept of phantom borders, i.e. borders that no longer exist, yet continue to structure the political and actual space.68 Administrative legacy also includes the types of historical layers of the border that activate in a certain socio‑political contexts and function in a phantom manner.

3For the borders in the Slovenian space, the administrative legacy of cadastral municipalities is the most significant.69 The smallest territorial units of the state, set out by the Habsburg officials and geometers in the early 19th century in order to allow for tax exploitation and the exertion of general control over the state's territory, are still alive. The former river beds, marked on cadastral maps, possess a strong "phantom" potential, which can activate itself in the appropriate political situation. In case of Mura, this happened during the dissolution of Yugoslavia and formation of two independent countries. The administrative legacy of the cadastral municipalities, which had merely possessed a "boring" technical character before 1991, suddenly became a "hot" political (and ideological) instrument afterwards.70

Sources and Literature

- “Zapisnik XI. zasedanja Stalne slovensko-hrvaške komisije za vodno gospodarstvo, Ljubljana, 9. in 10. 6. 2015.” Accessed August 5, 2017. http://gis.arso.gov.si/related/evode/vg_komisije/SLO-CRO_zasedanje%2011_junij%202015.pdf.

- ”Balvani na Muri.” Slobodna Dalmacija, September 15, 2006. Accessed August 5, 2017. http://arhiv.slobodnadalmacija.hr/20060915/novosti03.asp.

- ”PCA CASE NO. 2012-04 IN THE MATTER OF AN ARBITRATION UNDER THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA, SIGNED ON 4 NOVEMBER 2009 BETWEEN THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA AND THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA, FINAL AWARD, 29 June 2017.” Accessed August 5, 2017. https://pcacases.com/web/sendAttach/2172.

- Arbitraža, Vlada Republike Slovenije. Accessed October 10, 2017. http://www.vlada.si/teme_in_projekti/arbitraza/.

- Balažic, Simon. ”Meja na Muri.” In: 17. Mišičev vodarski dan, zbornik referatov. Maribor: Vodnogospodarski biro, 2006.

- Baumann, Norbert, Štefan Fartek, Rudolf Hornich, Jožef Novak and Oliver Rathschüler. Načelna vodnogospodarska zasnova za mejno Muro, I. Faza. Gradec/Graz: Stalna slovensko-avstrijska komisija za Muro, 2001.

- Belec, Borut. ”Hrvaška zemljiška posest v občini Lendava kot sestavina mejne problematike.” Dela 12 (1997), 183–93.

- Bizjak, Aleš. ”Transboundary Cooperation of the Republic of Slovenia – Obligations, Good Practices and Benefits.” Paper on the 2nd Workshop on Assessing the Water-Food-Energy-Ecoystem Nexus and Benefits of Transboundary Cooperation in the Drina River Basin, Belgrade, 8 – 9 November 2016. Accessed 3 August 2017. https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/documents/2016/wat/11Nov_08-10_Nexus_2nd-WS_Drinabasin_Belgrade/day_3/ab_UNECE_NEXUS_BELGRADE__Transboundary_Cooperation_091116.pdf.

- Brilly, Mitja, Mojca Šraj, Anja Horvat, Andrej Vidmar and Maja Koprivšek. ”Hidrološka študija reke Mure.” In: 20. Mišičev vodarski dan 2011, zbornik referatov. Maribor: Vodnogospodarski biro, 2011.

- Čepič, Zdenko. ”Oris nastajanja slovensko-hrvaške meje po drugi svetovni vojni.” In: Mikužev zbornik, edited by Zdenko Čepič, Dušan Nećak and Miroslav Stiplovšek. Ljubljana: Oddelek za zgodovino Filozofske fakultete, 1999, 201–16.

- Cipot, Boris and Sebastijan Kopušar. ”Hotižani: Dež prehitel diplomacijo.” Dnevnik, August 30, 2006.

- Cipot, Boris. “Hrvati so si privoščili še eno provokacijo.” Dnevnik, August 28, 2006.

- Demšar, Božo. ”Ureditev državne meje Slovenije s Hrvaško.” Geodetski vestnik 36, No. 4 (1992): 298–303.

- Dnevnik, September 14, 2006. ”Novinarje so pridržali, na meji specialci.”

- Dnevnik, September 15, 2006. ”Regulacija Mure izvor nesoglasij.”

- Eigmüller, Monika. ”Der duale Character der Grenze. Grenzsoziologie, die politische Strukturierung des Raumes.” In: Grenzsoziologie, die politische Strukturierung des Raumes, eds. Monika Eigmüller and Georga Vobruba. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaft, 2006.

- Fujs, Metka. “Izhodišča madžarske okupacijske politike v Prekmurju.” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 37, No. 2 (1997): 175–86.

- Hirschhausen, Béatrice von, Hannes Grandits, Claudia Kraft and Dietmar Müller. ”Phantomgrenzen im ostlichen Evropa, Eine wissenschaftliche Positionierung.” In: Phantomgrenzen, Räumen und Akteure in der Zeit neu denken, edited by Béatrice von Hirschhausen, Hannes Grandits, Claudia Kraft, Dietmar Müller and Thomas Serrier. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2015.

- Hozjan, Andrej. ”Reka Mura na Slovenskem v novem veku.” Ekonomska i ekohistorija 9 (2013):16–27.

- Jutro, April 25, 1922, 2.

- Kerec, Darja. ”Prekmurske Benetke leta 1925.” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 51, No. 3 (2011): 25–36.

- Komac, Blaž, Karel Natek and Matija Zorn. Geografski vidiki poplav v Sloveniji. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, 2008.

- Kontler, László. Madžarska zgodovina. Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 2005.

- Kos, Milko. Srednjeveški urbarji za Slovenijo, Urbarji Salzburške nadškofije. Ljubljana: Akademija znanosti in umetnosti, 1939.

- Kovačič, Fran. Ljutomer, Zgodovina trga in sreza. Maribor: Zgodovinsko društvo, 1926.

- Kralj, Marjeta and Mojca Zorko. ”Vrsta pozivov k pomiritvi.” Dnevnik, September 15, 2006.

- Lesjak, Aleš. ”Mura skozi čas.” In: 25. Mišičev vodarski dan, zbornik referatov. Maribor: Vodnogospodarski biro, 2014.

- Mayer, László and András Molnár, eds. Viri za zgodovino Prekmurja 1 / Források a Muravidék történetéhez 1. Szombathely – Zalaegerszeg: Arhiv županije Vas in Arhiv županije Zala, 2008.

- Mayer, László and András Molnár, eds. Viri za zgodovino Prekmurja 2 / Források a Muravidék történetéhez 2. Szombathely – Zalaegerszeg: Arhiv županije Vas in Arhiv županije Zala, 2008.

- Novak, Jožef and Vladimir Vratarič. ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri.” In: 14. Mišičev vodarski dan, zbornik referatov. Maribor: Vodnogospodarski biro, 2003.

- Ribnikar, Peter, ed. Sejni zapisniki Narodne vlade Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov v Ljubljani in Deželnih vlad za Slovenijo 1918-1921, 2. Del. Ljubljana: Arhiv republike Slovenije, 1999.

- Ribnikar, Peter. ”Zemljiški kataster kot vir za zgodovino,” Zgodovinski časopis 36, No. 4 (1982): 321–37.

- Šiftar, Vanek. ”Prekmurje 1918–1920.” Časopis za zgodovino in narodopisje 61, No. 1 (1989): 33–53.

- Simmel, Georg. ”Der Raum und die räumlichen Ordnungen der Gesellschaft.” In: Grenzsoziologie, die politische Strukturierung des Raumes, eds. Monika Eigmüller and Georg Vobruba. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaft, 2006.

- Slovenec, April 19, 1922, 2.

- Slovenec, February 5, 1922, 2.

- Slovenski gospodar, October 1, 1874, 345.

- Slovenski gospodar, June 1, 1938, 7.

- Slovenski gospodar, September 24, 1940, 4.

- Slovenski gospodar, October 8, 1878, 413.

- STA: BBC: Hotiza povod za nov konflikt na Balkanu (September 18, 2006). Accessed August 5, 2017. https://www.sta.si/1088579/bbc-hotiza-povod-za-nov-konflikt-na-balkanu-18-9.

- Uradni list Republike Slovenije 11/1998. “Uredba o ratifikaciji Pravilnika stalne slovensko-hrvaške komisije za vodno gospodarstvo.”

- Zajc, Marko. “Phantom and Possessed borders.” Conference Borders and Administrative legacy, Ljubljana, 24. – 26. 11. 2016. Accessed August 5, 2017. http://www.sistory.si/11686/37233.

- Zajc, Marko. “The slovenian-Croatian border: History, Representations, Inventions,” Acta Histriae 23, No. 3 (2015): 499–510.

- Žebot, Franjo. ”Mali obmejni promet,” Slovenski gospodar, December 28, 1922, 53.

- Žebot, Franjo. ”Resnica o mlinih in žagah ob Muri,” Slovenski gospodar, August 24, 1922, 35.

- Zelko Ivan. Zgodovina Prekmurja, Izbrane razprave in članki. Murska Sobota: Pomurska založba, 1996.

- Žerdin, Ali H.”Napeti petelini.” MLADINA.SI, September 21, 2006. Accessed August 5, 2017. http://www.mladina.si/92602/napeti-petelini/.

Marko Zajc

FENOMEN MEJNA REKA: PRIMER MURE

POVZETEK

1Avtor analizira dva vidika dolgega trajanja fenomena mejne reke na primeru reke Mure: a) razmerje med rečno strugo, mejno črto in antropogenimi učinki na reko; b) odkrivanje historičnih struktur skozi perspektivo mejnih sporov. “Zdravorazumsko” razumevanje mejnih rek predpostavlja ujemanje reke in mejne črte. Kljub temu je lahko v pokrajini in v kartografskih reprezentacijah velika razlika med tema dvema elementoma. Vsi odseki reke Mure, ki jih analiziramo v članku, so imeli v določenih obdobjih status mejne reke. Status mejne reke dolgem trajanju posredno vpliva na obliko i dinamiko rečne struge. Nekdanje rečne struge, ki so “ujete” v katastrskih mapah, imajo velik “fantomski” potencial, ki se lahko aktivira v pravem političnem trenutku. V primeru Mure se je to zgodilo z razpadom Jugoslavije in vzpostavitvijo dveh neodvisnih držav.

* The authors acknowledge the project Phenomenon of Border Rivers (J6-6830) was finacially supported by the Slovenian Research Agency.

** Research associate, PhD, Institute of Contemporary History, Kongresni trg 1, SI-1000 Ljubljana, marko.zajc@inz.si

1. Georg Simmel, ”Der Raum und die räumlichen Ordnungen der Gesellschaft,” in: Grenzsoziologie, die politische Strukturierung des Raumes, eds. Monika Eigmüller and Georg Vobruba (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaft, 2006), 22.

2. Monika Eigmüller, ”Der duale Character der Grenze. Grenzsoziologie, die politische Strukturierung des Raumes” in: Grenzsoziologie, die politische Strukturierung des Raumes, eds. Monika Eigmüller and Georga Vobruba (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaft, 2006), 55.

3. Jožef Novak and Vladimir Vratarič, ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri,” in: 14. Mišičev vodarski dan, zbornik referatov (Maribor: Vodnogospodarski biro, 2003), 119.

4. Simon Balažic, ”Meja na Muri,” in: 17. Mišičev vodarski dan, zbornik referatov (Maribor: Vodnogospodarski biro, 2006), 38.

5. Aleš Lesjak, ”Mura skozi čas,” in: 25. Mišičev vodarski dan, zbornik referatov (Maribor: Vodnogospodarski biro, 2014), 183–90.

6. Andrej Hozjan, ”Reka Mura na Slovenskem v novem veku,” Ekonomska i ekohistorija 9 (2013): 17.

7. Balažic, ”Meja na Muri,” 40.

8. Hozjan, ”Reka Mura,” 22.

9. Novak, Vratarič, ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri,” 114.

10. Ibid.

11. Hozjan, ”Reka Mura,” 26.

12. Ivan Zelko, Zgodovina Prekmurja. Izbrane razprave in članki (Murska Sobota: Pomurska založba, 1996), 68.

13. Novak and Vratarič, ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri,” 115.

14. Slovenski gospodar, 1. 10. 1874, 345.

15. Slovenski gospodar, 8. 10. 1878, 413.

16. Novak and Vratarič, ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri,” 116.

17. Darja Kerec, ”Prekmurske Benetke leta 1925,” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 51, No. 3 (2011): 26.

18. Novak and Vratarič, ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri,” 116.

19. Slovenski gospodar, 1. 6. 1938, 7.

20. Novak and Vratarič, ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri,” 118, 119.

21. Ibid., 120.

22. Lesjak, ”Mura skozi čas,” 188.

23. Novak and Vratarič, ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri,” 121.

24. Norbert Baumann, Štefan Fartek, Rudolf Hornich, Jožef Novak and Oliver Rathschüler, Načelna vodnogospodarska zasnova za mejno Muro, I. Faza (Gradec/Graz: Stalna slovensko-avstrijska komisija za Muro, 2001), 5.

25. Ibid., 17.

26. Novak and Vratarič, ”Mura nekoč, danes, jutri,” 119.

27. Balažic, ”Meja na Muri,” 40.

28. Mitja Brilly , Mojca Šraj, Anja Horvat, Andrej Vidmar and Maja Koprivšek, ”Hidrološka študija reke Mure,” in: 20. Mišičev vodarski dan 2011, zbornik referatov (Maribor: Vodnogospodarski biro, 2011), 158.

29. Balažic, ”Meja na Muri,” 40.

30. ”PCA CASE NO. 2012-04 IN THE MATTER OF AN ARBITRATION UNDER THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA, SIGNED ON 4 NOVEMBER 2009 BETWEEN THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA AND THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA, FINAL AWARD, 29 June 2017,” accessed August 5, 2017, https://pcacases.com/web/sendAttach/2172.

31. Aleš Bizjak, ”Transboundary Cooperation of the Republic of Slovenia – Obligations, Good Practices and Benefits,” 2nd Workshop on Assessing the Water-Food-Energy-Ecoystem Nexus and Benefits of Transboundary Cooperation in the Drina River Basin, Belgrade, 8 – 9 November 2016,” accessed August 3, 2017, https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/documents/2016/wat/11Nov_08-10_Nexus_2nd-WS_Drinabasin_Belgrade/day_3/ab_UNECE_NEXUS_BELGRADE__Transboundary_Cooperation_091116.pdf.

32. “Uredba o ratifikaciji Pravilnika stalne slovensko-hrvaške komisije za vodno gospodarstvo,” Uradni list Republike Slovenije 11/1998.

33. Milko Kos, Srednjeveški urbarji za Slovenijo, Urbarji Salzburške nadškofije (Ljubljana: Akademija znanosti in umetnosti, 1939), 12.

34. László Mayer and András Molnár, eds., Viri za zgodovino Prekmurja 1 / Források a Muravidék történetéhez 1 (Szombathely – Zalaegerszeg: Arhiv županije Vas in Arhiv županije Zala, 2008), 45.

35. Zelko, Zgodovina Prekmurja, 65.

36. Fran Kovačič, Ljutomer, Zgodovina trga in sreza (Maribor: Zgodovinsko društvo, 1926), 24.

37. Zelko, Zgodovina Prekmurja, 68.

38. Kovačič, Ljutomer, 25.

39. László Kontler, Madžarska zgodovina (Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 2005), 203.

40. Mayer and Molnár, Viri za zgodovino Prekmurja 1, 354.

41. Vanek Šiftar, ”Prekmurje 1918–1920,” Časopis za zgodovino in narodopisje 61, No. 1 (1989): 49.

42. László Mayer and András Molnár, eds., Viri za zgodovino Prekmurja 2 / Források a Muravidék történetéhez 2 (Szombathely – Zalaegerszeg: Arhiv županije Vas in Arhiv županije Zala, 2008), 330.

43. Peter Ribnikar, ed., Sejni zapisniki Narodne vlade Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov v Ljubljani in Deželnih vlad za Slovenijo 1918–1921, 2. del (Ljubljana: Arhiv republike Slovenije, 1999), 385.

44. Slovenec, February 5, 1922, 2.

45. Jutro, April 25, 1922, 2.

46. Slovenec, April 19, 1922, 2.

47. Franjo Žebot, ”Resnica o mlinih in žagah ob Muri,” Slovenski gospodar, August 24, 1922, 35.

48. Franjo Žebot, ”Mali obmejni promet,” Slovenski gospodar, 28. 12. 1922, 53.

49. Slovenski gospodar, September 24, 1940, 4.

50. Metka Fujs, ”Izhodišča madžarske okupacijske politike v Prekmurju,” Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 37, No. 2 (1997): 175-86.

51. Zdenko Čepič, ”Oris nastajanja slovensko-hrvaške meje po drugi svetovni vojni,” in: Zdenko Čepič, Dušan Nećak and Miroslav Stiplovšek, eds., Mikužev zbornik (Ljubljana: Oddelek za zgodovino Filozofske fakultete, 1999), 201-16.

52. Borut Belec, ”Hrvaška zemljiška posest v občini Lendava kot sestavina mejne problematike,” Dela 12 (1997): 186.

53. Božo Demšar, ”Ureditev državne meje Slovenije s Hrvaško,” Geodetski vestnik 36, No. 4 (1992): 298-303.

54. Arbitraža, Vlada Republike Slovenije, accessed October 10, 2017, http://www.vlada.si/teme_in_projekti/arbitraza/.

55. Balažic, ”Meja na Muri,” 41.

56. Blaž Komac, Karel Natek and Matija Zorn, Geografski vidiki poplav v Sloveniji (Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, 2008), 138.

57. Boris Cipot in Sebastijan Kopušar, ”Hotižani: Dež prehitel diplomacijo,” Dnevnik, August 30, 2006.

58. ”Novinarje so pridržali, na meji specialci,” Dnevnik, September 14, 2006.

59. ”Regulacija Mure izvor nesoglasij,” Dnevnik, September 15, 2006.

60. “Zapisnik XI. zasedanja Stalne slovensko-hrvaške komisije za vodno gospodarstvo, Ljubljana, 9. in 10. 6. 2015,” accessed August 5, 2017, http://gis.arso.gov.si/related/evode/vg_komisije/SLO-CRO_zasedanje%2011_junij%202015.pdf.

61. ”Balvani na Muri,” Slobodna Dalmacija, September 15, 2006, accessed August 5, 2017, http://arhiv.slobodnadalmacija.hr/20060915/novosti03.asp.

62. Boris Cipot, “Hrvati so si privoščili še eno provokacijo,” Dnevnik, August 28, 2006.

63. Marjeta Kralj and Mojca Zorko, ”Vrsta pozivov k pomiritvi,” Dnevnik, 15. 9. 2006, 4.

64. Ali H. Žerdin: ”Napeti petelini,” MLADINA.SI, September 21, 2006, accessed August 5, 2017, http://www.mladina.si/92602/napeti-petelini/.

65. STA: BBC: Hotiza povod za nov konflikt na Balkanu? (September 18, 2006), accessed August 5, 2017, https://www.sta.si/1088579/bbc-hotiza-povod-za-nov-konflikt-na-balkanu-18-9.

66. Marko Zajc, “The slovenian-Croatian border: History, Representations, Inventions,” Acta Histriae 23, No. 3 (2015): 502.

67. PCA CASE NO. 2012-04, 125.

68. Béatrice von Hirschhausen, Hannes Grandits, Claudia Kraft and Dietmar Müller, ”Phantomgrenzen im ostlichen Evropa, Eine wissenschaftliche Positionierung,” in: Béatrice von Hirschhausen, Hannes Grandits, Claudia Kraft, Dietmar Müller and Thomas Serrier, eds., Phantomgrenzen, Räumen und Akteure in der Zeit neu denken (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2015), 7-13.

69. Peter Ribnikar, ”Zemljiški kataster kot vir za zgodovino,” Zgodovinski časopis 36, No. 4 (1982): 334.

70. Marko Zajc, ”Phantom and Possessed borders,” Conference Borders and Administrative legacy, Ljubljana, 24. – 26. 11. 2016, accessed August 5, 2017, http://www.sistory.si/11686/37233.