Evaluation Remarks About Slovenian Parliamentary Democracy at Its Twenty-Fifth Anniversary

UDC: 328(497.4)"2014/2016"

IZVLEČEK

OCENA SLOVENSKE PARLAMENTARNE DEMOKRACIJE OB NJENI PETINDVAJSETLETNICI

1V članku je z namenom podati oceno dosedanjih praks slovenske parlamentarne demokracije podan kronološki pregled sprememb in prevladujočih demokratičnih vzorcev v državi od prvih parlamentarnih volitev po sprejemu ustave do aktualnega časa. Osrednjo mesto analize, ki je v prvem delu članka utemeljena prvenstveno na statističnih podatkih v drugem delu pa na sekundarnih virih, med njimi spoznanjih že izvedenih raziskovalnih študij ter medijskih zapisov, je namenjeno parlamentarnemu in vladnemu vedenju političnih strank v posameznem volilnem obdobju. Analiza pokaže, da je bila slovenska parlamentarna demokracija v prvem, poosamosvojitvenem obdobju pretežno predvidljivo osredotočena v temeljni demokratični razvoj in ni beležila pomembnejših sprememb skozi čas. Na drugi strani pa predvsem zadnja tri volilna obdobja (t.i. drugo obdobje demokracije) kažejo na bistvene spremembe od prvotno zastavljenega delovanja in jih zaznamuje prevlada notranjih strankarskih interesov ter konfliktov, kar ima učinek na celotni demokratični prostor v državi. Na podlagi vsega prikazanega je eno od ključnih spoznanj članka, da politične stranke v Sloveniji ohranjajo temeljno vlogo gradnika parlamentarne demokracije, vendar pa izvajanje njihovih vlog in aktivnosti tako znotraj parlamentarne kot vladne arene v zadnjih obdobjih pospešeno opozarja na premislek o osrednjem poslanstvu ter demokratičnih funkcijah političnih strank. Prav tako je zlasti v zadnjem obdobju možno zaznati, da se možnosti nezanesljivega in nepredvidljivega volilnega rezultata za stranke povečujejo sorazmerno z njihovimi notranjimi ter medstrankarskimi konflikti, ki na parlamentarno demokracijo države mečejo izrazito negativno podobo.

2Ključne besede: Državni zbor Republike Slovenije, demokracija, volivci, vlada, spremembe

ABSTRACT

1In order to evaluate the existing practices of the Slovenian parliamentary democracy, the author conducted a chronological overview of the shifts in prevailing democratic patterns, starting with the first parliamentary elections after the country gained independence onwards. Parliamentary and governmental political party behaviour was central to the analysis and, thus, was analysed using both statistical data and secondary sources, which primarily consisted of academic and research papers and media records. The analysis revealed that Slovenian parliamentary democracy in the initial (first) decade was according to the electoral data predictable and by programme orientation oriented towards democratic development. However, over the past three election cycles (second decade), the situation began to change quickly, indicating a predominance of internal party interests and conflicts that affect the country’s entire democratic arena. One of the main findings of the article suggests that political parties in Slovenia remain a fundamentally important pillar of parliamentary democracy, but their roles and activities within the parliamentary, governmental and other arenas increasingly warn of their central mission and democratic system functions. It can be detected that the potentials for electoral uncertainties increase with the intensities of internal and inter-parties’ conflicts which all give distinctly negative connotation to the country’s parliamentary democracy.

2 Key words: National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia, Democracy, Voters, Government, Changes

1. The Place of the Political Parties in the Parliamentary Democracy

1In Europe, political parties are an essential aspect of parliamentary-party democracy,1 as they allow the parliamentary arena to function normally. Because of this, political parties represent the core of modern politics.

2With the advent of mass democracy in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the existence of a direct link between the state and individuals became more and more unrealistic; this shift has contributed to the legitimisation of political parties as intermediaries between individual citizens and the state.2 As a result, political parties have taken on the role of an interface, or a connecting point between the citizens and state institutions. Parties have begun to function as a key element of the integration of the people’s will and the respective governing authorities. In this regard, the implementation of universal and free voting has led to an assertion of power by the political parties.

3Despite their relatively recent appearance on the political stage, parties have made such a strong mark on contemporary politics and democracy that twentieth-century democracy could be best described as a ‘party democracy’.3 Parties not only became an indispensable part of the democratic society’s existence; they also became a fundamental factor for changes in democratic societies.4

4Up until this point, democratic theorists did not consider the role of political parties to be an important factor in the changing patterns of democracy. Numerous studies on the institutional and procedural functions of political parties exist,5 including some that explore the relationship between citizens and the state,6 but few have focused on political parties as the third fundamental constitutive pillar of democracy.

5With regard to a system-wide democracy, political parties exist and work on two levels:

- Level 1 refers to the platform political parties create for themselves in the external environment; this includes their attitudes and their making related to their voters, to their work in political institutions etc.

- Level 2 refers to internal party dynamics, which are reflected in their internal political processes, how they perceive their own mission and jurisdictions in the system and, consequently, any adequate cadre, financial, intellectual and other operational resources allocated to them.7

6The most recent research has found that parties are losing relevance as vehicles of representation, mobilisation and channels for interest articulation and aggregation. All of this together makes parties increasingly incapable of carrying out their essential function and, consequently, have had an indirect impact on citizens’ decreasing trust and confidence in political institutions and politics in general.8

7The primary aim of this article is to recognise and assess the patterns of Slovenian parliamentary democracy; these patterns are identified using electoral experiences from the independence of the state onwards. The behaviour of the parliamentary and governmental political parties are at the centre of the analysis. In order to structure the chronological overview, the analysis focuses on each electoral term as an individual unit in which the prevailing frameworks represent the wider political context, upgraded with the political party arenas’ main specifics of the analysed time periods. The analysis uses statistical data and other secondary sources – which consist primarily of academic research papers and media records – to explore these themes.

2. The Slovenian Experience as an Example: The Broader Political Context of Parliamentary Democracy from Independence Until Today 9

1After gaining independence in 1991, the first election of representatives to the National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia took place in 1992. There have since been an additional seven election cycles, and ten governments have been elected to the National Assembly.10

2Basic electoral indicators11 show that on average, 20 political parties participate in parliamentary elections. At least 17 political parties participated in the 2008 and 2014 elections. In contrast, 26 parties participated in the 1992 elections. Bigger variations in the number of competing political parties between the two consecutive elections were not recorded.

| 1992 | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2008 | 2011 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of candidates | 1475 | 1300 | 1007 | 1395 | 1182 | 1300 | 1246 |

| No. of competing parties | 26 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 20 | 17 |

| No. of elected parties | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| No. of newly elected parties | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| No. of unelected parties | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| No. of coalition parties | 14, later 23 and then 2 | 3 dropping to 2 | 5 dropping to 4 | 4 | 4 | 15 (SDS term) / 24 (PS term) | 3 |

3Source: Adapted from the Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia (2016), National Electoral Commission (2016) and Government of the Republic of Slovenia (2016)

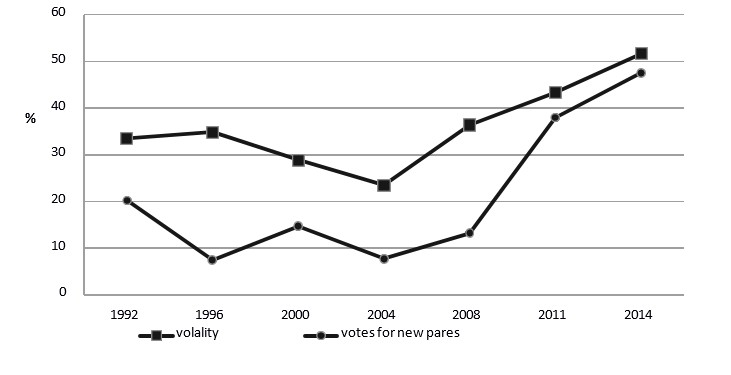

4The number of elected, re-elected and unelected parties remains stable. On average, two new parties are elected in each election, whereas two parties fail re-election. This data supports the volatility phenomena, which suggests that political party electoral support changes according to their past electoral success. Based on statistical data, since Slovenia’s 2004 elections (and even more so from 2008 onwards), the volatility rates have reflected the electoral success and after that immediate and complete failure of new political parties to enter the parliament.

1Source: Adapted from Kustec Lipicer and Henjak (2015)

5On average, the government coalition consists of four parties. On average, within one government office term, two shifts occur in coalition partners, whether due to their resignation or to their replacement by the prime minister. The only exception was the coalition in the 2004–2008 term, the only one in Slovenian parliamentary history to sustain a complete electoral period term in the initial composition.12

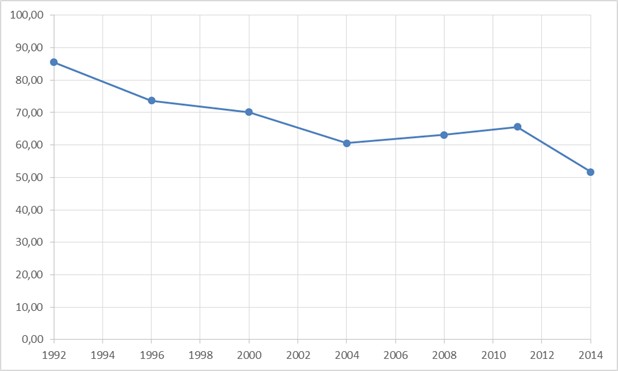

6These circumstances have resulted in a significant decrease in trust in the government and the National Assembly generally and in the political parties specifically. Over the past two electoral periods, the level of trust in political parties has fallen below 5 %.13 However, the average electoral participation is still slightly higher than 70 %. After 2004, the turnout rate dropped to the aforementioned average, with participation in the last elections in 2014 barely exceeding 50 %, all of which points to a decrease in the legitimacy of electoral participation, something that needs to be taken into consideration in the democratic political system.

1Source: National Electoral Commission (2016)

3. Parliament 1992–1996

1Slovenia’s first National Assembly of the Republic election in 1992 was influenced by the early period of democracy. Based on constitutional norms, internal visions of action and fundamental political visions regarding how to model and develop a democratic state and market system, political parties – together with the parliament and the government, which function as fundamental pillars of democracy – began to build up their democratic experience.14 Internal party conflicts that related to new social movements’ internal democratic processes were prevalent and ultimately resulted in their separation or integration of social movements into political parties formations which consequently indicated a farewell of the former from the political system.15 In the shadow of these processes, the first coalition was very diverse. Consisting of parties from both the left and the right, this new coalition was led by the relative winner of the elections, the left-centred liberal democracy of Slovenia (LDS), and its president, Janez Drnovšek, became the prime minister.

2In March 1994, the affair ‘Depala vas’ was revealed. Though it was the only one, it induced a huge polemic of the aforementioned office term. This affair also directly affected the governmental coalition’s internal instability. The coalition leading, the left-winged LDS, was primarily a reason for deposing the then Minister of Defence, which led to the resignation of the right positioned social democratic party SDSS, whose members included said Minister of Defence, from the governmental coalition. Further, in 1994, the then Foreign Minister from the quota of another, also in the right political pole positioned partner Slovenian Christian Democrats, SKD, also resigned from the Government. However, despite this, the SKD remained in the coalition. Six months before the 1996 general elections, the left-wing social democrats, ZLSD, the second of the four coalition partners, resigned from the coalition.16

4. Parliament 1996–2000

1The second term of the National Assembly was again marked by the relative victory of the LDS party. The party’s president, Janez Drnovšek, formed a new governmental coalition, this time with the newly elected, interest-driven Democratic Party of Retired Persons of Slovenia, DeSUS, and the center–right agrarian party of Slovenian People’s Party, SLS.

2The coalition, despite its constant internal tensions, endured until six months before the next election, where the National Assembly, on the recommendation of the Prime Minister, called for a vote of no confidence in the government. The coalition did not pass. This was the first time in history that the National Assembly voted that they had no trust in the government.17 Instead of calling early elections for a six month period, the government was taken over from the (already) united former right coalition party SLS and the right-wing opposition parties SKD (SLS + SKD), as well as the Slovenian Democratic Party SDS (formerly the SDSS). The coalition was lead by the prime minister, Andrej Bajuk from SLS + SKD. The main characteristic marking this half-year long right-wing coalition was the numerous politically driven personal replacements.18

3Aside from another round of internal coalition tensions and other parliamentary-party turbulences, the second parliamentary term remained influenced by the further development of the market-economic model, as well as the starting processes of integrating the country into the international arena. After the Depala vas affair, another similar military-police political affair emerged (Vič Holmec) during the same term, together with the already mentioned affairs connecting the political cadre replacements in this period’s last months.

5. Parliament 2000–2004

1The third parliamentary elections were again won by the left-positioned LDS, this time with the vast majority of 36,26 of the votes. LDS President, Janez Drnovšek, assembled a governmental coalition for the third time. This third coalition was described as a ‘large heterogeneous coalition’.19 In the beginning of the mandate, the coalition was composed of five parties, all of which had already cooperated with the mandatary back when he had been leading the two previous governments.20 In 2002, Prime Minister Drnovšek ran and was subsequently elected for the President of the Republic. The new prime minister within the same coalition became Drnovšek’s former party colleague.21 Tone Rop, the former minister of finances, became the ruling party’s new president.

2Strong disagreements emerging in the coalition almost a year before the new parliamentary elections led to the resignation of the right SLS ministers. In this parliamentary term, an active opposition action was recognised. Also, a vote of no confidence in the government, which did not pass, was proposed by the right leading opposition parties SDS and Nsi.22 A programme interested governmental report on Slovenia’s 2000–2004 development23 was prepared for this occasion, and it served as a valuable written side-effect remark of this political act.

3This period was positively influenced by external politics, namely, formal membership in the EU and NATO. External factors, along with the encouraging economic indicators and, consequently, social indicators,24 showed the successful realisation of the country’s development model that was set a decade ago, which was focused on the economic and international consolidation and stabilisation of the country.

4In contrast to the increasingly numerous internal political affairs and party conflicts, decreased trust in the fundamental political institutions and lower electoral participation were notable in this period and thus influenced the processes of democratic political institution consolidation. Most notably, in 2003, Udba.net media archive was released by the right-wing parties, which referred to the list of previous employees in the communist times.25 Parallel to this, some other examples of pre-election and election allegations of appointing political staffing26 were present. From the stated internal and mutual party relation perspective, the Slovenian political development first showed bigger democratic wounds and prevented a smooth continuation of democratic growth.

6. Parliament 2004–2008

1After the fourth elections in 2004, the mandate to form the government was taken over by the centre-right coalition for the first time. The governmental coalition included the election winner, SDS, the right parties, NSi and SLS, and the centrist DeSUS party. All parties had already had prior experience in the previous coalitions.

2The country had successfully completed the process of integration and entry into the international arena during this term, which they did by adopting the European currency, the Euro, presiding, as the first CEE member state, to the Council of the EU in 2008 and implementing the so-called ‘borderline rules’ of the Schengen area.27 The initial development model in the economic, social and international segments was successfully completed.28 However, the consolidation of the state and government democratic structures, on the other hand, could not be confirmed. The mandate was influenced by a number of internal and international high-profile affairs, such as regulating the problems of the Roma people, the rights violations of the so-called ‘erased’, the beginning of the Partia affair, the Piranski zaliv affair and numerous personnel changes, which were thought to be linked with the political parties.29 Despite the fact that all of the democratic institutions had been established for over a decade and a half following the country’s independence, their final consolidation and credibility was constantly undermined by a number of internal scandals and affairs, conflicts, personnel exchanges and, with that, logically related institutional instability. All of this had the same common denominator: the parliamentary and, specifically, the ruling government political parties’ uncertainties.

3In this term, internal coalition disagreements culminated again half a year before the next elections, with the vote of confidence in the parliament. The tensions of the coalition partners SLS and DeSUS complicated the internal coalition relations, as did a new proposal by the prime minister to vote for the future of this government. The government passed a vote of confidence and was the only one in the country’s current government and parliamentary history to endure over the same coalition structure until the end of the regular term.

7. Parliament 2008–2011

1The fifth parliamentary elections were marked by a tight election result. The mandate to form a government was again assigned to the coalition of the leftist parties. The coalition was included the leading Social Democratic party, SD, which led the government for the first time; the barely elected LDS; the newly established political party, Zares (although the majority of the Zares consisted of members of the old LDS); and the permanent coalition partner, DeSUS.

2This period, despite the programme affinity and the manageable number of coalition partners, was characterized by continuous internal issues, coalition unrest and scandals. Furthermore, this period was also affected by the global economic crisis, to which the country had responded with excessive borrowing, thereby putting a growing burden on the national budget.30

3Initial personnel moves by Prime Minister Borut Pahor led to the coalition partners’ request to convene an extraordinary session of the coalition summit in 2009. A wave of resignations from ministers and other high officials followed in 2010. Almost one-third of the ministers were replaced. Resignations continued in 2011, following the resignation of the Minister of Higher Education, Science and Technology and the president of the Zares party. Interpellations were actively filled, and all governmental reform proposals were obstructed by the opposition; later, proposals were also obstructed by the voters on the referenda. Six referendums were tendered during this parliamentary term, namely, arbitration, reform referendums on the mini jobs, a pension reform referendum and a referendum on the Law on the Prevention of Labour and Employment in the black, as well as a referendum on the RTV contribution and archives.31

4This mandate was also marked by a number of internal political scandals in addition to the aforementioned personnel affairs – for example, the unsuccessful rehabilitation of the banking system; the construction of the sixth block of the Šoštanj Thermal Power Plant; the insolvency of once successful companies, such as Vegrad, Istrabenz, Mura; and government Falcon aircraft. Other corruption scandals included the bullmastiffs affair, the Ultra affair, the rental of the National Bureau of Investigation premises and the Dimic affair.

5In terms of Slovenia’s international activities, this mandate was marked by the agreement of the Republic of Slovenia’s and the Republic of Croatia’s prime ministers in November 2009, which stated that open border conflict issues would be resolved through international arbitration. Besides this, the appearance of the top Slovenian politicians in the international arena visibly faded in all other topics. Civil servants were often involved in political decision-making processes on behalf of the state, or the state was not represented in aforementioned processes.32 The situation above was expressed when first DeSUS and later Zares resigned from the coalition a year before the new election was called. The National Assembly requested for a vote of confidence on the Prime Minister’s proposal and, for the second time in history, the government did not pass the vote. Therefore, the President of the Republic convened the first early elections for autumn 2011.

8. Parliament 2011–2014

1The results of the 2011 autumn elections brought a major twist to the parliamentary political arena. Competition for votes between old and successful new political parties became a pure fact, with the new ones gaining more and more electorate trust.

2Despite the very real prospect of early parliamentary elections, political parties were not as sufficiently prepared, either financially or organisationally, as the political parties in the previous National Assembly elections. The role of the two new political parties established just before the elections – left-positive Slovenia (PS) and centre-right Civic List (DL)33 – was one of the key innovations of the pre-electoral, the electoral and, subsequently, the post-election period from the party perspective. Both parties personalised their leaders, who were both politically recognisable figures, namely, Zoran Janković, the second-time elected mayor of the capital city of Ljubljana (PS), and Gregor Virant, one of the hitherto most prominent members of the SDS party and the Minister of Public Administration from 2004 to 2008 (DL). These two parties occupied 41 % of all parliamentary seats. For the first time since 1992, after 12 years as the country’s leading government party, the LDS did not pass the electoral threshold. The party received only 1.48 % of the votes. The only national party in Slovenia, the SNS, received only 1.80 % of the votes in the 2011 elections and so did not enter the parliament. Zares, which had been elected into the parliament immediately after its establishment before the 2008 parliamentary elections, also failed to pass the electoral threshold. However, after a three-year break between 2008 and 2011, the NSi reached the electoral threshold and re-entered the parliament.

3The existing old political parties, shocked by the election results but still more politically experienced, formed the government coalition, after the newly established left-wing party PS together with the future members of a coalition failed to nominate the Speaker of the Parliament and afterwards the government. Hence PS left the mandate to the second best party, the experienced right-wing SDS.

4The SDS composed a short-term government with a five-member coalition that was, despite its size, quite close ideologically. The SDS coalition partners were also a new political party, DL, two old right-wing coalition partners SLS and Nsi and a constant in all coalitions present party DeSUS. Soon after the government’s formation, Prime Minister Janez Janša (SDS) was first (and again) accused of direct political intervention in replacements and nomination of staffing since the beginning of the term,34 and afterwards the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption released a report pointing to the financial accusations against the prime minister and, a few weeks later, the president of PS, the largest parliamentary party,35 which resulted in the resignation of both politicians from their senior positions. Janša resigned as prime minister after the National Assembly rejected the vote of confidence, while Janković temporarily resigned as the PS party president. Leadership of the PS party was temporarily and ‘as a last resort’ left to Alenka Bratušek after the aforementioned incident. Alenka Bratušek became a mandatary and, in March 2013, she took over the leadership of the ninth Slovenian government, which was composed of the left-social democratic party SD and former coalition partners DL and DeSUS. However, internal conflicts in the PS, along with the new success of the PS founding president at the party electoral congress, led to the resignation of Prime Minister Bratušek just one year after she took over the government. The President of the Republic called for early elections for the second time in a row in late spring 2013.36

5This term was marked by the disability of both governments, which were facing many of their internal and between political parties’ pressures, divisions and ambitions, despite their attempts to solve the economic and financial crisis and their work to return the country to the international arena. However, the biggest international slip at the end of mandate was Bratušek’s self-nomination for the European Commissioner.37

9. Parliament 2014 -

1The seventh parliamentary election, which was also the second preliminary election in Slovenia, was implemented at the beginning of summer vacation on July 13, 2014. The election results again followed a similar parliamentary arena patterns as the previous elections.

2The biggest winner of the 2014 elections was the newly established centre Party of Miro Cerar, or the SMC. Once again, this party had been established just before the elections and had one main driving figure: the publicly well-known and respectful constitutional lawyer Miro Cerar. The party gained 40 % of the votes and was renamed the Modern Centre Party in early 2015;it formed a left-centred government coalition in September 2014 together with the left-wing social democrats, SD and DeSUS.

3Insights into the parliamentary arena show that in addition to the SMC, the threshold was as well achieved by two new left-wing parties, the United Left (ZL) and nearly passed the electoral threshold new party of the former prime minister, ZaAB. In contrast to the past elections, these three political parties did not enter the parliamentary arena. Two of them were successful new parties at the former elections and members of the governmental coalition. The third unsuccessful party was the right-positioned SLS, the historically oldest party, as well as a frequent, but generally conflictual, member of many former governmental coalitions.

4Similar to the recent terms of office coalition, work so far has been marked by internal party accusations and tensions, as well as remarks on the lack of leadership capacities. A set of opposition activities has been well activated against the work of the coalition.38 During the current government activity from autumn of 2014 until nowadays, the public-financial conditions were stabilised, particularly the control over the allowed budget deficit. Additionally, legally transparent frames for managing state assets were accepted, economic growth increased importantly, while unemployment rate decreased to the level before the crisis in 2008. A greater emphasis was placed on the protection and management of natural resources. The government, however, once again more actively cooperates in the international community, particularly through participation in migration policy.39

10. Conclusion

1Slovenian’s 25 year-old parliamentary democracy has revealed some patterns throughout its quite active and also turbulent development. These patterns can be divided into two periods: 1) the implementation period for democratic state model and its positioning in the international environment (1992–2008) and 2) the period of internal political and party crises and the search for a new model of growth (2008–present).

2The state democracy’s first period was characterised by a clear and distinct, ideologically distant programme vision, as well as by a focus on the international environment and the internal ability of the political parties and elites to establish the democratic management foundations and the modes of governing. In contrast, the second, still ongoing period is characterised by political parties’ prevailing dominance throughout the political system (or so-called partitocracy).40 Political parties express tendencies for controlling all of the state (sub)systems, which are not and should not depend on political parties’ policies and influence (e.g. cartelisation patterns).41 Therefore, political parties are also involved in most of the state's affairs and political staffing. This means that parties do not use their powers and functions to mediate and control the political system’s conflictual issues and problems but are actively helping to shape them. As political parties (as well as individuals in these parties) are still pursuing their own interests, they are constantly causing disagreements and turbulences. Not only does this not lead to forming successful coalition partnerships, it also disables individual party functioning, as well as it also enables the winning potentials of completely new and undefiled parties to enter the parliament or even win the forthcoming elections.

3Effective management of the coalition so far corresponds to the great importance of having individuals in politics whose knowledge and skills correspond to transparent political leadership, as well as the importance of controlling party speculations. These speculations include different kinds of pressure that coalition partners put on a leading party, as well as how some parties tactically chose to resign just before the specific term of government ran out. In this regard, it is clear that political parties forming the governmental coalition play a direct and decisive role in political stability. Hence, in terms of government experience, we can see that the failure of all of the previous coalition governments was directly related to the internal coalition partners’ affairs and disagreements. However, they never directly related to the success of opposition parties’ pressures to the coalition work.

4There are also not real differences possible to detect between left- and right- positioned political parties, in addition to coalitions that

share the same patterns over time in all of the three analysed arenas. Some differences in this regard could potentially be noticed in the cases of new political parties, but as they would be mostly Mayflys up until today, lacking the capacities and experiences for implementing stable and sustainable democratic stability through their parliamentary group and coalition work, their long-term effect on democracy is mostly unseen.

5With the 1992 elections as a starting point, a total of 148 political parties have competed at the elections, while 51 have constituted the country’s parliamentary arena afterwards. 12 new political parties have been elected to the National Assembly, though 14 of them have not been successful in re-entering the parliament, and only one of the older parties has been voted back into Parliament. Not a single one of the newly elected political parties has been re-elected in the subsequent elections, though the old political parties are on the whole losing their election success with each election cycle. Because of all of the stated, the nature of the Slovenian parliamentary democracy is still considered reasonable, although it signals clear warnings of the risks, especially those of the practices and functions undertaken inside the party arenas. Citizens still recognise political parties as the intermediators between their will and the political institutions’ work. This is still reasonably moderate, although on one hand political participation as seen through election turnout data is constantly falling. On the other hand the share of effective votes is very high, but the volatility rate shows that voters more and more give voice for the political newcomers and activations from the civil society initiatives in the last three terms.

6One of the main findings of the article suggests that political parties in Slovenia remain a fundamentally important pillar of parliamentary democracy, but their roles and activities within the parliamentary, governmental and other arenas increasingly warn of their central mission and democratic system functions. It can be detected that the potentials for electoral uncertainties increase with the intensities of internal and inter-parties’ conflicts which all give distinctly negative connotation to the country’s parliamentary democracy.

Sources and Literature

- Dalton, Russell J., David M. Farrell and Ian McAllister.Political parties and democratic linkage. How parties organize democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- "European Journal of Political Research." Political Data Yearbook. Slovenia, 2016. Accesed 20 June 2016. URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)2047-8852/homepage/slovenia.htm.

- Fink - Hafner, Danica. Nova družbena gibanja – subjekti politične inovacije. Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 1992.

- Gallagher, Michael, Michael Laver and Peter Mair. Representative Government in Western Europe. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

- Gašparič, Jure. Slovenski parlament. Politično-zgodovinski pregled od začetka prvega do konca šestega mandata (1992–2014) – 1.0. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2014. Accesed 29 June 2016. URL: http://www.sistory.si/SISTORY:ID:26950.

- Katz, Richard S. "Party in Democratic Theory." In: Handbook of Party Politics, eds. Richard S. Katz and Daniel Crotty, 34–47. London: Sage, 2006.

- Krašovec, Alenka and Ladislav Cabada L. "Kako smo si različni. Značilnosti vladnih koalicij v Sloveniji, Češki republiki in na Slovaškem."Teorija in praksa 50, No. 5/6 (2013): 717–35.

- Krouwel, Andre. "Party Models." In: Handbook of Party Politics, eds. Richard S. Katz and Daniel Crotty, 249–270. London: Sage, 2006.

- Kustec Lipicer, Simona and Andrija Henjak. "Changing dynamics of democratic parliamentary arena in Slovenia. Voters, parties, elections." Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino 55, No. 3 (2015): 84–104.

- Kustec Lipicer, Simona and Niko Toš. "Analiza volilnega vedenja in izbir na prvih predčasnih volitvah v Državni zbor." Teorija in praksa 50, No. 3-4, (May-August 2013): 503–29, 685.

- Lajh, Damjan and Zdravko Petak, eds. EU Public Policies Seen from a National Perspective. Slovenia and Croatia in the European Union. Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2015.

- Ljiphart, Arendt. Patterns of Democracy. Yale: Yale University Press, 2012.

- Lorenčič, Aleksander. Prelom s starim in začetek novega. Tranzicija slovenskega gospodarstva iz socializma v kapitalizem (1990–2004). Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2012.

- Mair, Peter and Ingrid van Biezen. "Partymembership in twenty European democracies, 1980–2000." Party Politics, No. 7 (2011): 5–21.

- Mair, Peter. "Party System Change." In: Handbook of Party Politics, eds. Richard S. Katz and Daniel Crotty, 63–75. London: Sage, 2006.

- Noč, Boštjan. Kazalniki zadolženosti Slovenije. Paper, prepared for the Conference Statistični dnevi, 2011. Accesed 20 May 2016. URL: http://www.stat.si/StatisticniDnevi/Docs/Radenci2011/Noc-Kazalniki_zadolzenosti-prispevek.pdf.

- Pečauer, Marko. "Skoraj vsak mandat se konča s krizo." Delo, 19 September 2008. Accesed 22 May 2016. URL: https://m.delo.si/clanek/174052.

- Prunk, Janko and Tomaž Deželan, eds. Dvajset let slovenske države. Maribor: Aristej and Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, Center za politološke raziskave, 2012.

- Toš, Niko, ed. Vrednote v prehodu VIII. Slovenija v srednje in vzhodnoevropskih primerjavah 1991–2011. Ljubljana and Wien: Univerza v Ljubljani, Fakulteta za družbene vede and IDV-CJMMK – Edition Echoraum, 2014.

- Van Biezen, Ingrid and Richard S. Katz. Democracy and Political Parties. Paper, prepared for the workshop ‘Democracy and Political Parties’, ECPR Joint Sessions, 2005, 14–19. Granada, April 2005. Available at URL: https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/3402a19c-2e82-4b30-bf30-6a423927d5b0.pdf.

- Ware, Alan. Citizens, parties, and the state. A reappraisal. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Zajc, Drago, Samo Kropivnik and Simona Kustec Lipicer. Od volilnih programov do koalicijskih pogodb. Analiza politične kongruence. Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2012.

- "Freedom House." Nations in Transit. Slovenia, 2016. Accesed 20 June 2016, URL: https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2016/slovenia.

- "KPK."Odločitve in mnenja komisije ǀ Komisija za preprečevanje korupcije, 2012. Accesed 20 June 2016. URL: https://www.kpk-rs.si/sl/nadzor-in-preiskave/odlocitve-in-mnenja-komisije.

- Arhiv glavnih novic; Vlada Republike Slovenije, 2016. Accesed 5 July 2016. URL: http://www.vlada.si/medijsko_sredisce/glavne_novice/.

- Government of the Republic of Slovenia. Accesed 15 September 2016. URL: http://www.vlada.si/en/about_the_government/governments_of_the_republic_of_slovenia/.

- Kadrovski blitzkrieg – Mladina.si, 2012. Accesed 30 June 2016. URL: http://www.mladina.si/109350/kadrovski-blitzkrieg/.

- National Electoral Commission. Accesed 15 September 2016. URL: http://www.dvk-rs.si/index.php/en.

- Official Gazette of teh Republic of Slovenia. Accesed 15 September 2016. URL: https://www.uradni-list.si/.

- Reports on National Assembly's work in the parliamentary terms Accesed 15 September 2016. URL: http://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/deloDZ/raziskovalnaDejavnost/Knjige.

- STA (Arhiv novic). Accesed 30 June 2016. URL: https://www.sta.si/.

- Žerdin, Ali H. "Udba.net." Udba.net | MLADINA.si. Accesed 21 July 2016. URL: http://www.mladina.si/61653/18-04-2003-udba_net/?utm_source=dnevnik%2F18-04-2003-udba_net%2F&utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=oldLink.

OCENA SLOVENSKE PARLAMENTARNE DEMOKRACIJE OB NJENI PETINDVAJSETLETNICI

POVZETEK

Simona Kustec Lipicer

1Namen članka je oceniti dosedanje prakse slovenske parlamentarne demokracije. Skozi kronološki pregled sprememb in prevladujočih demokratičnih vzorcev vedenja političnih strank preučujemo parlamentarno in vladno delovanje, kot se kaže v državi od prvih parlamentarnih volitev po sprejemu ustave do aktualnega časa.

2Članek je razdeljen v dva večja sklopa, od katerega enega (po obsegu sicer manjšega) predstavlja analiza temeljnih volilnih podatkov, drugega (po obsegu prevladujočega dela besedila) pa prikaz ključnih lastnosti vladnega in s tem posredno tudi parlamentarnega delovanja političnih strank v posameznem mandatnem obdobju, kot jih prikazujejo sekundarna spoznanja že izvedenih raziskovalnih študij ter medijskih zapisov.

3Od prvih demokratičnih volitev po sprejemu slovenske ustave leta 1991 je bilo do danes izvedenih sedem parlamentarnih volitev, oblikovanih pa je bilo deset različnih vlad. Skupaj je na volitvah v preučevanih obdobjih tekmovalo 148 političnih strank oziroma v povprečju 20 na posamezne volitve. Od volitev leta 1992 dalje je parlamentarni prag prestopilo 51 političnih strank, od njih 12 povsem na novo, medtem ko jih 14 na naslednjih volitvah ni bilo ponovno izvoljenih. Stopnja izvoljivosti povsem novih političnih strank v obdobju zadnjih treh volitev izjemno narašča, hkrati pa v tem istem času število tekmujočih strank v primerjavi s prejšnjimi volitvami upade za blizu četrtino (podoben upad beležimo tudi v številu tekmujočih strank med prvimi volitvami leta 1992 in naslednjimi leta 1996). Značilnost parlamentarnega in strankarskega prostora v obdobju zadnjih treh parlamentarnih volitev je tudi izjemen volilni uspeh novih strank ter izraziti neuspeh na naslednjih volitvah, saj do sedaj nobena od njih na naslednjih volitvah ponovno ne prestopi parlamentarnega praga. Iz volitev v volitve prav tako upada volilni uspeh starih strank, ki pa v nasprotju z novimi strankami praviloma presežejo volilni prag, a zasedejo vsakič manj sedežev v parlamentu. Ponovna vrnitev v parlament po predhodnem volilnem neuspehu je do sedaj uspela le politični stranki iz t.i. skupine starih strank ter nobeni od novih. Nasploh je za slovenski parlamentarni prostor značilno, da je stopnja volilne nestanovitnosti (t. i. volatility) v nasprotju s stabilnimi starejšimi demokracijami visoka. Vidno upada tudi stopnja volilne udeležbe.

4V drugem delu članka del analize dinamike vladnega delovanja in vedenja v posameznem volilnem obdobju, ki je utemeljen prvenstveno na pregledu spoznanj že izvedenih raziskovalnih študij ter medijskih zapisov. V nasprotju s prikazanimi temeljnimi volilnimi podatki, ki se skozi obdobja ne spreminjajo fundamentalno, analiza v drugem delu članka pokaže na bolj živahno, a hkrati tudi vse bolj negativno dinamiko razvoja slovenske strankarske in s tem povezano parlamentarne demokracije. To je glede na vzorce dosedanjih praks in doseženih učinkov možno razdeliti v dve prevladujoči obdobji, in sicer: 1. pozitivno obdobje (1992 – 2008), ki ga zaznamuje pretežno predvidljiva osredotočenost države v temeljni demokratični razvoj in povzemanje dobrih demokratičnih praks, aktivno sodelovanje v mednarodnem prostoru, vključno s polnopravnim vstopom države v EU in NATO, poudarek na spoštovanju človekovih pravic ter tržnega liberalizma starih razvitih demokracij; ter. 2. negativno obdobje (2008 - ), ki še vedno traja in ga zaznamuje predvsem čas znotraj in medstrankarskih konfliktov in ozkega zasledovanja lastnih strankarskih interesov, v katerem lastnosti prvega obdobja povsem umanjkajo.

5Ključno spoznanje članka utrjuje spoznanje, da politične stranke v Sloveniji ohranjajo temeljno vlogo gradnika, a tudi krvnika parlamentarne demokracije. Izvajanje njihovih vlog in aktivnosti tako znotraj parlamentarne kot vladne arene v zadnjih obdobjih namreč pospešeno opozarja na premislek o osrednjem poslanstvu ter demokratičnih funkcijah političnih strank. Prav tako je zlasti v zadnjem obdobju možno zaznati, da se možnosti nezanesljivega in nepredvidljivega volilnega rezultata za stranke povečujejo sorazmerno z njihovimi notranjimi ter medstrankarskimi konflikti, ki na parlamentarno demokracijo države mečejo izrazito negativno podobo.

* Full Professor, PhD, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Kardeljeva ploščad 5, SI-1000 Ljubljana, simona.kustec-lipicer@fdv.uni-lj.si

1. Alan Ware, Citizens, parties, and the state. A reappraisal (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, 1988).

2. Ingrid van Biezen and Richard S. Katz, Democracy and Political Parties. Paper, prepared for the workshop ‘Democracy and Political Parties’, ECPR Joint Sessions, 2005 (Granada, April 2005), 1, available at URL: https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/3402a19c-2e82-4b30-bf30-6a423927d5b0.pdf.

3. Note 2.

4. Richard S. Katz, "Party in Democratic Theory," in: Handbook of Party Politics, eds. Richard S Katz and Daniel Crotty (London: Sage, 2006), 44.

5. Peter Mair, "Party System Change," in: Handbook of Party Politics, eds. Katz and Crotty, 63–75.

6. Arendt Ljiphart, Patterns of Democracy (Yale: Yale University Press, 2012).

7. Andre Krouwel, "Party Models," in: Handbook of Party Politics, eds. Katz and Crotty, 249–70. Peter Mair and Ingrid van Biezen, "Partymembership in twenty European democracies, 1980–2000," Party Politics, No. 7 (2011): 5–21. See also Note 5.

8. Michael Gallagher, Michael Laver and Peter Mair, Representative Government in Western Europe (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005). Russell J. Dalton, David M. Farrell and Ian McAllister, Political parties and democratic linkage. How parties organize democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

9. Chapter based on the following data and other sources' webpages: National Electoral Commission, accesed 15 September 2016, URL: http://www.dvk-rs.si/index.php/en. Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, accesed 15 September 2016, URL: https://www.uradni-list.si/. Government of the Republic of Slovenia, accesed 15 September 2016, URL: http://www.vlada.si/en/about_the_government/governments_of_the_republic_of_slovenia/. Reports on National Assembly's work in the parliamentary terms, accesed 15 September 2016,URL: http://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/deloDZ/raziskovalnaDejavnost/Knjige. "Freedom House," Nations in Transit. Slovenia, 2016, accesed 20 June 2016, URL: https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2016/slovenia. "European Journal of Political Research," Political Data Yearbook. Slovenia, 2016, accesed 20 June 2016, URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)2047-8852/homepage/slovenia.htm. For more details about the statistical data and in-depth analysis see also Simona Kustec Lipicer and Andrija Henjak, "Changing dynamics of democratic parliamentary arena in Slovenia. Voters, parties, elections,"Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino55, No. 3 (2015).

10. The 1990 elections may be mentioned as a forerunner of the first after–independence elections to the National Assembly in 1990. In the 1990 elections, 80 members were elected in each of the three assembly chambers, which were the Socio–Political Chamber, the Chamber of Associated Labour and the Chamber of Communities. Government was formed based on the outcome of the Sociopolitical Chamber elections, and this was conducted by the coalition of the Demos in the period of 1990 to 1992. Due to disagreements in the Demos coalition, the government was led by the left Liberal Democracy of Slovenia, LDS just before the first parliamentary elections (from May 1992 till the end of February 1993).

11. More details about the statistical data and in-depth analysis are in Kustec Lipicer and Henjak, "Changing dynamics of democratic parliamentary arena in Slovenia."

12. Drago Zajc, Samo Kropivnik and Simona Kustec Lipicer, Od volilnih programov do koalicijskih pogodb. Analiza politične kongruence (Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2012).

13. Niko Toš, ed., Vrednote v prehodu VIII. Slovenija v srednje in vzhodnoevropskih primerjavah 1991–2011 (Ljubljana and Wien: Univerza v Ljubljani, Fakulteta za družbene vede and IDV-CJMMK – Edition Echoraum, 2014).

14. Aleksander Lorenčič, Prelom s starim in začetek novega. Tranzicija slovenskega gospodarstva iz socializma v kapitalizem (1990–2004) (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2012).Jure Gašparič, Slovenski parlament. Politično-zgodovinski pregled od začetka prvega do konca šestega mandata (1992–2014) – 1.0 (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2014), accesed 29 June 2016, URL: http://www.sistory.si/SISTORY:ID:26950. Janko Prunk and Tomaž Deželan, eds., Dvajset let slovenske države (Maribor: Aristej and Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, Center za politološke raziskave, 2012).

15. Danica Fink - Hafner, Nova družbena gibanja – subjekti politične inovacije (Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 1992).

16. Marko Pečauer, "Skoraj vsak mandat se konča s krizo," Delo, 19 September 2008, accesed 22 May 2016, URL: https://m.delo.si/clanek/174052.

17. The merger of the coalition party SLS with the opposition, SKD, led to the resignation of all of the ministers of SLS from the government. The ministers of SLS constituted almost half of the government. Furthermore, the appointment of new ministers was tied to a vote of no confidence in the new government, but was not elected.

18. One of the key people of the ruling coalition parties became Telekom's CEO; the director of the Tax Administration was illegally deposed with more than a hundred government officials. More in STA (Arhiv novic), accesed 30 June 2016, URL: http://sta.si.

19. Alenka Krašovec and Ladislav Cabada L., "Kako smo si različni. Značilnosti vladnih koalicij v Sloveniji, Češki republiki in na Slovaškem,"Teorija in praksa 50, No. 5/6 (2013): 717–35.

20. The SDS was the only party that the coalition had already cooperated with in the past, but was also not invited into the current large coalition. The SLS, which was responsible for the governmental crisis before the end of the previous mandate, also participated in the coalition.

21. The party membership of Janez Drnovšek was frozen when he was elected for the President of the Republic. In 2006, Drnovšek resigned from the LDS.

22. Immediately after the 2000 elections and subsequent internal party disagreements, the NSi were formed out of the resigned members and deputies from before the election merged the SLS + SKD. After the formation of the NSi, the party SLS + SKD was again renamed the SLS.

23. More details Arhiv glavnih novic; Vlada Republike Slovenije, 2016, accesed 5 July 2016, URL: http://www.vlada.si/medijsko_sredisce/glavne_novice/.

24. Lorenčič, Prelom s starim in začetek novega.

25. Ali H. Žerdin, "Udba.net,"Udba.net | MLADINA.si, available at: http://www.mladina.si/61653/18-04-2003-udba_net/?utm_source=dnevnik%2F18-04-2003-udba_net%2F&utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=oldLink.

26. More details in STA (Arhiv novic), accesed 30 June 2016, URL: https://www.sta.si/.

27. Note 26.

28. Note 24.

29. Note 26.

30. Boštjan Noč, Kazalniki zadolženosti Slovenije. Paper, prepared for the Conference Statistični dnevi, 2011, accesed 20 May 2016, URL: http://www.stat.si/StatisticniDnevi/Docs/Radenci2011/Noc-Kazalniki_zadolzenosti-prispevek.pdf.

31. Simona Kustec Lipicer and Niko Toš, "Analiza volilnega vedenja in izbir na prvih predčasnih volitvah v Državni zbor," Teorija in praksa 50, No. 3-4 (May-August 2013): 503–29, 685.

32. Damjan Lajh and Zdravko Petak, eds., EU Public Policies Seen from a National Perspective. Slovenia and Croatia in the European Union (Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2015).

33. The Movement for Sustainable Development of Slovenia (TRS) was established as an alternative to the party system in October 2011. The Party for Sustainable Development of Slovenia was then formed from the political wing of the movement. The mentioned political party participated in the parliamentary elections in 2011, but, despite initial good opinion polls and prognoses, did not exceed the threshold for entry into parliament. However, it did achieve a comparable election result as the old, once successful parties SNS and LDS and a half higher result than the former parliamentary coalition party Zares. The TRS members were mostly recognisable personalities from public life and value – oriented intellectuals left.

34. Kadrovski blitzkrieg – Mladina.si , 2012, accesed 30 June 2016, URL: http://www.mladina.si/109350/kadrovski-blitzkrieg/.

35. "KPK,"Odločitve in mnenja komisije ǀ Komisija za preprečevanje korupcije, 2012, accesed 20 June 2016, URL: https://www.kpk-rs.si/sl/nadzor-in-preiskave/odlocitve-in-mnenja-komisije. STA (Arhiv novic), accesed 30 June 2016, URL: URL: https://www.sta.si/.

36. STA (Arhiv novic), accesed 30 June 2016, URL: https://www.sta.si/.

37. Note 36.

38. Note 36.

39. STA (Arhiv novic), accesed 30 June 2016, URL: https://www.sta.si/.

40. Note 7.

41. Note 41.